Rebun Island

During my first sojourn in Japan, my neighbors in Nagoya forewarned me that summer in that city was somewhat difficult to endure. Taking the hint, I planned to escape the city during the university’s summer holidays and travel northward. With little money to spare, it occurred to me that if I backpacked my way northward—which I assumed would be cooler—I could leisurely see other parts of the country.

When July arrived, I began my tightly budgeted travel up the Japan Sea coast. My projected expenditures were two out of three items per day: food, transportation expenses, and shelter. Food was a necessity, so the only choice was whether to pay train or bus fare and sleep outdoors in my sleeping bag or to find cheap lodging and walk or hitchhike northward the next day.

In preparation, I had learned the expression “nokishita demo ii desuga”, meaning that any place with a roof would be appreciated if I could spread out my sleeping bag. My first night was spent in the graveyard of a temple, under a large bell. Not wishing to surprise or offend anyone, I was careful to wake up before sunrise and slip away before anyone saw me. Other nights were spent on park benches, on beaches, or in youth hostels.

Hitchhikers in those days were not common, but I was a tall foreign guy, who must have appeared to be nonthreatening, so I was picked up by families, traveling salesmen, and lots of truck drivers. Over six weeks on the road, at least a hundred kind drivers helped me see the northern half of Japan.

After three weeks or so and passing through Hakodate, Cape Erimo, and Wakkanai, I reached Rebun Island. I was exhausted and decided to spend several nights in a minshuku. Early on the second morning of my stay, two new Japanese friends and I were awakened by the master of the lodging house. He asked us if we wanted to do a day’s work for a neighboring fishing family. The three of us were quite willing, so we had a quick breakfast and walked down the road to the shore where a family with two boats were busily preparing to harvest kelp called “kombu”.

On days when weather conditions were perfect, the fishermen’s cooperative (“kumiai”) set a two-hour limit on a special type of harvesting. Members of the cooperative were allowed to take a rowboat out into the bay, pull up kombu from the roots in the sea bottom, row in, unload, and repeat the process until the signal to end was sounded. Our family had two boats, one for the father and one for his son. Our job was to quickly unload each one, so it could quickly go back out. This was a chance for the local men to make serious money, so they worked feverishly during the time allotted. We had to follow suit.

After unloading a boat, we stretched the kombu out on the rocky beach so it would dry in the sun. The three of us followed the instructions of the grandmother and the son’s wife, and when the siren went off at the end of the two hours, the men of the family returned to shore with their last full boatloads. Once that was unloaded and put out to dry, we only needed to turn over the previous boatloads so the other side would dry better.

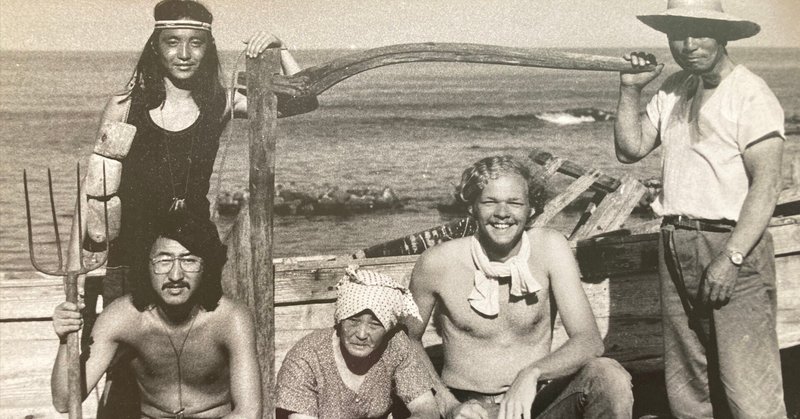

In addition to our pay—which was one full-day’s travel expenses for me—we were treated to a hot bath, a meal with the family, some kind of energy drink, and photos with everyone.

I spent another three weeks returning south, seeing all of the Tohoku festivals and visiting Nikko before returning to Nagoya. But the memories of that day on Rebun that has stood out over the years. Yes, it was a unique experience of doing something entirely unimaginable. But more than anything, it was being treated not as a foreigner, but as a temporary member of a family, far away from home.

(674 words)

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?