Buddhist Preachings of Hell and the Arts: Explanatory Illustrations, Rakugo, and Plays - Part 1

By Kohichi Watari, School of Global Japanese Studies, Meiji University

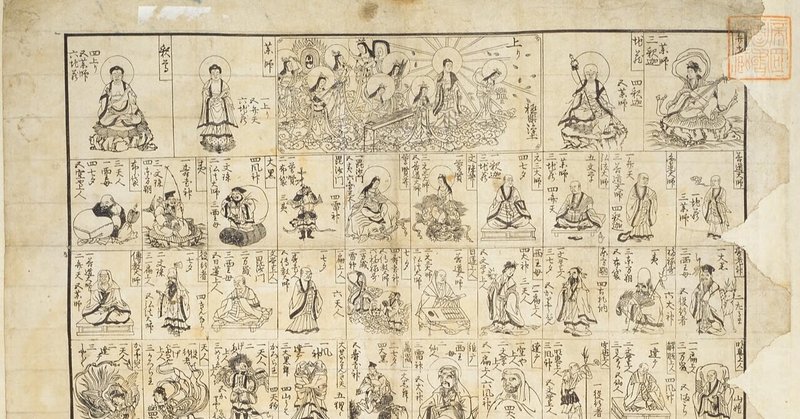

Illustration: Jikkai Sugoroku (Collection of the National Diet Library)

Introduction

I had the good fortune of coming across documentary footage from the production TERA in Kyoto. Though theater is not one of my primary relaxations, I was nevertheless asked to contribute some commentary.

In all honesty, my impression after the first viewing was, “I don’t understand this.” At the same time, there were certain elements of it that were quite fascinating, and couldn’t help but pique my interest. For one, the TERA project stages its productions at temples, and this made me consider how Buddhism, temples, and the performing arts are historically connected.

Another fascinating part were the lines from a character who fell down a well and ended up on a journey to Buddhist hell. This prompted me to remember a particular legend that I will revisit later in this article.

Finally, there is a segment at the end in which the audience is asked rapid-fire questions on the spot, and they can respond “yes” by striking a wooden fish. The questions are posed in such quick succession that it allows almost no time to think, and it occurred to me that this serves to bring the unconscious mind—karma, as it were—to the fore. Obviously, I’ve never killed anyone. Nor have I ever screamed “drop dead” at someone, or told them so on social media. But when asked if I’ve ever wished someone dead, I almost reflexively strike the fish. To put it another way, even someone who has not committed the act of murder through deeds and words is, in a karmic sense, technically still committing murder simply by considering the act in their mind. When I pass on to the underworld, surely Great King Enma (also known as Great King Yama)—judge of the dead—will see right through me and sentence me straight to hell.

As mentioned above, I am not well-versed enough to do a proper theatre critique—and fortunately, it does not appear that is what is expected of me—so I will instead offer some idle musings on the topic of Buddhist preachings regarding hell.

The Afterlife in Japanese Buddhism

Before we delve into the main topic, let us first consider how Japanese Buddhism explains the afterlife.

Souls are reincarnated among the six realms or “wandering worlds”: hells (nakara), hungry ghosts (preta), animals, demi-gods (asura), humans, and gods (deva). (Heaven is still considered a wandering world, and the mortal world is considered the “second best” of the realms.) Therefore, death and rebirth repeat in perpetuity with the soul being reborn among the realms. This is called the rokudō-rinne.

The realms of the rokudō-rinne are impure—polluted with worldly attachment. The liberation from worldly attachment in the impure realms and attaining enlightenment to ascend to nirvana is called gedatsu. There are only two ways to attain gedatsu: one perseveres with their own strength to practice and attain enlightenment, or one beseeches the power of the Buddha—asking a higher power for help. The latter is part of the core faith of Jōdo Buddhism, also known as Pure Land Buddhism, which states that one can ascend to the Western Pure Land (or Western Paradise) by praying for the power of Amida (Amitābha). Upon death, practitioners are greeted in the Pure Land (Paradise) by Amida, bodhisattvas, and other heavenly figures.

Hell and the other realms are written about in detail in the first chapter Onrieido (“Abhorrence of an Impure World”) of a religious text called the Ōjōyōshū (“The Essentials of Rebirth in the Pure Land”) authored by Genshin, with the second chapter Gongujōdo (“Seeking Rebirth in Paradise”) featuring the Pure Land. The text is arranged in a way that the reader detests and wants to remove themselves from the six realms, and then explains the happiness of paradise in a way that makes them want to seek to enter the purer realms. The third and later chapters explain what one needs to do to end up in the Pure Land, coming to the conclusion that is accomplished nenbutsu—an invocation entreating a higher power for salvation. (That said, the Ōjōyōshū was created before the time of Hōnen—the father of Pure Land Buddhism, and thus ascetic practice predates Amida Buddha). However, it appears that these crucial sections were not often read by those other than scholar monks.

A dead person’s soul remains in an intermediate state of existence between death and rebirth for forty-nine days. Every seven days they undergo a trial, and when their next realm to be reincarnated is decided, they are born again as flesh and blood in that realm. The judges of the trial of the underworld are the ten kings, including King Enma, with the kings divided into two groups: the seven kings presiding from the seventh to forty-ninth day, and the three kings presiding over a "retrial" on the hundredth day, one year after, and three years after death. Traditionally, one's reincarnation was believed to be decided automatically based upon one's own deeds performed while alive. However, it came to be that rites such as the gyakushu (pre-memorial rites) and memorial services held by others for the already deceased were held to encourage a more favorable judgment from the underworld tribunal.

In Japan, belief in the ten kings further developed into belief in the thirteen buddhas. In other words, the seventh, thirteenth, and thirty-third anniversaries of death were added to form the thirteen kings, and in Japan, each of the thirteen kings has its own true buddha form—for example, King Enma, who presides over the fifth trial on the fifty-seventh day, has the true form of the Jizō Bodhisattva (Kṣitigarbha). The idea of making offerings to these thirteen Buddhas on thirteen specific days (a total of thirteen times a year) before one's death was a popular belief during medieval times, with the idea being that one made offerings to them in advance, one would gain an advantage in these underworld trials after death. Memorial services are based on the idea of "ekō," or turning the merits one has accumulated over to others, and the bereaved family holds a Buddhist service on the anniversary of the death of the deceased to turn the merits over to the deceased. It has been seen since ancient times, but it has taken root in “funeral Buddhism,” and even today, Buddhist rituals are held on the forty-ninth day and on the one-year anniversary of the death.

Buddhism and the Performing Arts

Somber Buddhist lectures often did not draw in a target audience for conversion. Thus, it was inevitable that Buddhist preaching would shift to a form of performance that was more easily understood and brought more people into the faith. Otherwise, the lessons would fall on deaf ears, especially if the listeners were common villagers. In preaching and sermons long ago, the metaphors and origin stories were accessories to the Buddhist teachings, but they no doubt added melodies and musical accompaniment to those stories, mixed with sweeping gestures to draw in a crowd. Evoking laughter and tears were essential to conveying the messages of these sermons. In this way, many of Japan’s traditional orated performance arts were borne from the sermons and teachings conducted at Buddhist temples, including narratives such as jōruri (dramatic ballads, especially the form known as gidayū-bushi), sekkyō-bushi (sutra-based ballads); storytelling like rakugo; and dramatic readings such as kōdan.

Explanatory Illustrations of Buddhist Hell

Hell is a subject that has featured in sermons and other activities at Buddhist temples since olden times. By preaching on the terrors of hell, those looking to convert others could better steer people toward the teachings of salvation. Therefore, pointing at paintings of hell while preaching—both at temples and outside—proved effective in illustrating these terrors to the commonfolk during conversion activities. Simply explaining paintings is something that can be done by anyone who understands the content depicted within, but doing this as an entertaining performance is another story. It is said that dedicated “picture explainers” were once employed at Shitennōji Temple in Osaka and other temples. These individuals were of low birth, and because their livelihood depended on their narration, one could imagine how their craft transformed into a performance art. Even those who were not specialists explained the same paintings over and over, enough so that they naturally perfected their ability to narrate in an entertaining fashion.

After the Ōjōyōshū offered a more systematic and detailed description of the six realms of existence paintings illustrating the concepts of hell and these realms became more prominent in Japan. For instance, a copy of the 15-scroll Rokudō-e, a national treasure at Shōjuraikō-ji Temple in Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, was used as the basis for performative explanation when the scrolls were aired out during the Obon festival season, and the script for this performance is still extant today.

In the Edo period, only the first two chapters of the Ōjōyōshū—were transcribed in Waji eiri (an illustrated Japanese-language version of the work), with the first volume covering stories about hell, the second volume with stories about the Six Realms, and third volume with stories about Paradise. This version was then broadly published and distributed. In this manner, the illustrations seem to have served as references for numerous other works of art depicting hell and the six realms that reached temples in different regions of Japan, and which, in turn, were used for pictorial explanations when brought out for airing during Obon.

Numerous relics with images of the ten kings of hell, including in these paintings of hell and the elements of the Rokudō-e also remain and have been used in such explanations. Belief in the ten kings—which derives from China—spread with the creation and evolution of “funeral Buddhism”. It is believed that sermons teaching people about memorial services that would raise the chances of a deceased family member being reincarnated into a more favorable realm would be accompanied by pictorial explanations of the ten kings, which thusly became firmly entrenched in the Buddhist tradition.

[Century Akao Collection, Keio Univesity]

Examples of this are detailed in Japanese folk art researcher Shōichi Ozawa’s narration album, “Wandering Performing Arts in Japan” (title also translated as “Wanderers Performing Arts in Japan”). Kyōdō Fujitake (1892-1985), a Shinshū-sect monk at Kyōzenji temple (Inabe City, Mie Prefecture), was famous for his explanations on illustrations of the ten kings featured as a journey through the intermediate, hell, and paradise realms. Fujitake’s explanation of the ten kings illustrations, entitled “Hell and Heaven: A Travel Diary of the Underworld” was performed in the Shōwa style of evoking laughter and tears, and prompted families to consider a memorial service for their ancestors. “Wanderers Performing Arts in Japan” also features a recording of a roadside spectacle on the grounds of Shitennōji Temple—one employing a similar theme entitled “Hell and Heaven,” which also likely was derived from the temple’s explanatory illustrations of hell.

“Hell and Heaven: A Travel Diary of the Underworld” by Kyōdō Fujitake

Kohichi Watari

Professor at the School of Global Japanese Studies, Meiji University. He received his bachelor’s degree from the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Saitama University, and his master’s degree from the Graduate School of Humanities, Tokyo Metropolitan University. He completed coursework in a Ph.D. program at the Graduate School of Letters, Toyo University. He specializes in the cultural history of Japan. His interests include Japanese religion and culture (especially the history of jizō belief), changes of foreign cultures after their introduction to Japan and “Japan” as viewed by foreigners. His published works include “Enmei Jizō Bosatsu Kyō Jikidanshō” as author/editor (Bensei-sha), “Nihon Bungaku to Bukkyō” vol. 7 “Reichi” as coeditor (Iwanami Shoten), “Jūshikanbon Jizō Bosatsu reigenki” as coeditor/collation editor/commentator (Miya Shoten), “Muromachi monogatari sōshishū” (in the series of Shinpen Nihon koten bungaku zenshū, vol. 63) as coeditor/author/collation editor/translator/commentator (Shōgaku-kan), “Ojizō-san No Iru Sekai: Sukui no Setsuwa, Rekishi, Minzoku” (Keiyū-sha), and many others. He is a member of the Society of Japanese Religious and Cultural History, the Folklore Society of Japan, the Narrative Literary Society, the Japan Society of Buddhism Literature, the Japan Society of Folk-Literature and Traditions, and a member and acting director of the Study Group of Explanatory Illustrations (until 2011).

(Translated from Japanese by John Townsend)

Related Programs

TERA in Kyoto is available for on-demand streaming until Sunday, December 26, 2021. Please visit the link below for details, including ticket information.

* Tickets are available for purchase until Sunday, December 12.

頂いたサポートは、打ち合わせ時のコーヒー代として、私たちの創作活動の励みとなります。 Your support supplies our team with an extra cup of coffee to boost creative energies. Thank you!