Correspondence: On the Music of TERA and เถระ - 3. Last Letter from Kyojun (Music Attached)

by Kyojun Tanaka and Great Lekakul

Kyojun Tanaka and Great Lekakul are both musicians who worked respectively on the Japanese and Thai versions of TERA. As performers and researchers, they exchanged letters online on their musical approaches and the creation process of TERA. In this post, we will present the fifth letter of their six-letter correspondence, with original music attached.

Read the previous post

Read from the first letter

Letter No.5 - From Kyojun to Great

Dear Great san,

Thank you for yet another thoughtful response. I have a feeling that my last email was slightly hard to follow, and the lack of explanation might have perplexed you a little. So now I’d like to try to clarify what I meant last time.

First of all, what I wanted to avoid in TERA is the kind of music that would be considered “gorgeous” and “serious.” In soundtracks for Japanese theatre, movies, and so on, “gorgeous” and “serious” music usually consists of:

Arrangements in which string instruments are the main feature, such as Western orchestras or chamber music

Acoustic piano solo music

Musical styles that imitate traditional Japanese music

Musical pieces with these characteristics give people the impression that they are “gorgeous” and “serious” (these days, jazz is starting to come into this category, too). In my opinion, Japanese people perceive these kinds of music as rather authoritative and high culture (or, at least, it’s safe to say that not many people would think of them as “cheaper” than the sound I tried to create for TERA). I thought bringing in music like the above into a Japanese temple would make it too “gorgeous” and “serious” for me.

In contrast, percussion instruments can create “serious” music, but it also has the power to make “trifling” music—something more flippant, more comical. I think that element was well suited for TERA’s musical direction.

As for the synthesizers and the tunes in the songs Mitchan (Miho) sings, I had in mind the sounds of Japanese pop music in the latter half of the 90s. From the perspective of music trends in the 2010s, it sounds rather outdated. What used to sound “gorgeous” in the old days is now the opposite: it sounds shabby and ridiculous.

Another context is that the 90s was a decade when the Japanese economy gradually started going downhill (and I feel that the economy has never recovered since then, continuously falling little by little). Before that, in the 80s and early 90s, things were on the rise. If you compare the music of the falling era with that of the rising era, there’s something about it that’s darkened by a shadow—Japanese people sense it, somehow. So that’s another reason why I incorporated late-90s sounds into TERA. I wanted to evoke that hint of a shadow, and then overlay a kind of “foreboding of death and destruction” on that feeling. To flavor the “trifling” music of “nonsense” with a bit of uneasiness.

Now, my father, who is a monk, frowned upon such intentions of mine very much. After watching our performance, he told me, “What are you thinking, playing music like that in a temple? Make it more gorgeous and serious.” Sometimes, it’s hard for a father and a son to understand each other.

It’s intriguing to hear about how you used various instruments to create a soundscape of earthquakes, waterfalls, and so on. In my case, I didn’t try to represent anything specific. Instead, I attempted to capture the rather abstract idea of “Buddhism as an unknown” (the incomprehensibility of Buddhism that many Japanese people feel) in sound. Differences like these seem to stem largely from how Buddhism is received in Thailand and in Japan. I think it is really interesting to think about.

Your description of the relationship between music and Buddhism in Thailand is very lucid, and I was nodding in agreement many times while reading your letter. One difference between Thailand and Japan is that Thailand is a nation of Theravada Buddhism, whereas Japan follows Mahayana Buddhism. Moreover, I think Thai people are much more devout in believing in Buddhism than Japanese people. (In Japan, I think it’s not so common for people to have a Buddha statue or image in their house, even if they are a follower of Buddhism.) From the perspective of a Thai person, maybe it’s puzzling to see a Japanese person saying, “I don’t really get Buddhism.”

In your letter, you wrote that “music and Buddhist religion in Thailand cannot be separated.” Besides Thailand’s Piphat and Myanmar’s Saing Waing, it seems fairly unusual that a country’s traditional music gets performed so regularly during the rituals of temples and Buddhism. In Japan, some traditional music do relate to Buddhism, but in recent times, it’s not rare for Western musical performances to take place in a temple’s main building (even EDM live shows can happen there).

What is Japanese Buddhist music? If we asked Japanese people, the majority would likely answer “okyō (sutra chanting).” There are also Buddhist songs of praise, like the equivalent of Christian hymns, but their composers are often influenced by Western music techniques, and they can’t be considered purely Japanese (they often use piano and chorus vocals). You wrote that “music and the sound identity of Thai instruments illustrate the social meaning and the way in which people think in Buddhism,” but it’s hard to say the same about Japan. I thought about reflecting this kind of background in my music for TERA as well, instead of sweeping the issue under the rug.

Well then, while this exchange will end with your next letter, this conversation showed me just how clearly and earnestly Buddhism is followed in Thailand, as well as how inseparable the connection is between traditional music and Buddhism. This interests me a great deal because in TERA Japan, I was reflecting ideas that were exactly the opposite. Though both TERA pieces share the same theme of Buddhism and temples, we took it in such different directions, even just in terms of music.

One thing I’d like to add is that while Japanese people may think “I don’t really get Buddhism,” that doesn’t mean they are ridiculing or making light of it. Even while they don’t comprehend it, they still interact with it with a certain respect—that’s for sure. But it’s still obscure to them. So for Japanese people today, the first step towards building a different relationship with Buddhism may be just accepting that they don’t really understand it and then, without pretending like they know everything, approaching it with open sincerity. To me, TERA portrays that first step.

Since TERA gave me this opportunity to discuss music and Buddhism with you, I feel that my world has expanded again a little more through this exchange. I am very grateful—thank you so much. That’s all from me. For your last letter, if you could comment freely on anything—for example, your impressions about this TERASIA project, or my intentions behind TERA’s music—that would be wonderful.

(Translated from Japanese by Yui Kajita)

Postscript

Sakata-san (Yukari) suggested that we add some music to the blogpost of our correspondence. She said I can use an existing song, but as a musician, I decided to make something related to our letters, even if it was simple. Based on the rhythm used for the music in TERA, I made a small piece of about two minutes with percussion rhythm patterns. I know you are very busy, so I think it's fine to post this song as it is. But if you would like to play and record an instrument for this song, it would be delightful for me, that we can conclude this correspondence by exchanging music.

Read the Next Post

Related Programs

Theatre performances TERA in Kyoto and TERA เถระ are available for on-demand streaming from Friday, November 19 until Sunday, December 26, 2021. Please visit the link below for details including ticket information.

* Tickets are available for purchase until Sunday, December 12.

Artist Bios

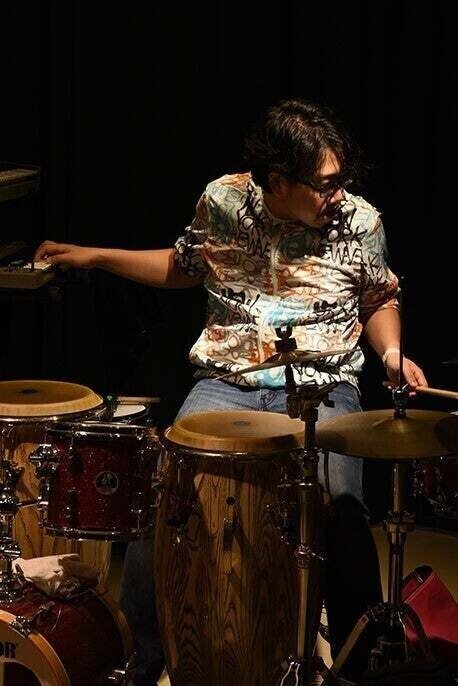

Kyojun Tanaka

Born in Tokyo in 1983, Kyojun Tanaka is a drummer, percussionist, and composer. He started his musical career since he was a student in Tokyo University of the Arts. Following time with the likes of Naruyoshi Kikuchi’s dCprG, he attained his Ph.D., and is currently a rhythm-addicted university staff who travels the world in search of rhythms that make one want to “embrace.” Kyojun performs with his unit MIDOUTEI and the Latin jazz band Septeto Bunga Tropis. He is also engaged in the research and musical training of hsaing waing at the National University of Arts and Culture in Myanmar. “Tera” (2018) was his first participation in Yukari Sakata’s works, and he also performed in its shows in Tunisia (2019).

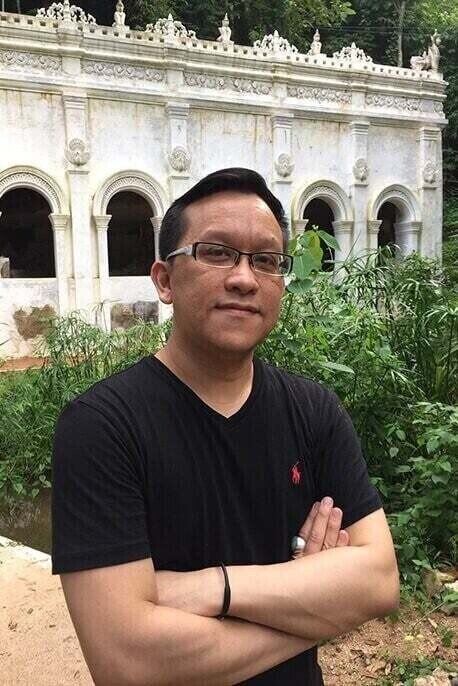

Great Lekakul

After graduating in music from Mahidol University, Great lectured in Japan at Kanda International Language Studies University, teaching music and religions in South East Asia and Thai music performances. Afterward, he studied for his doctorate at SOAS, the University of London in Ethnomusicology. After his graduation, he became a lecturer at SOAS.

With his specialties in Thai and experimental music, he became a member of Korphai, the renowned contemporary Thai music band since 2000. He also co-produced the musical soundtrack of Homrong films on Thai music in 2004. He also got selected as the Thai musicians representative to perform in the Asia Traditional Music Orchestra in Seoul, South Korea. In 2019 he produced and performed his music in Mahajanaka performing arts, highlighting the Buddha’s past life, with Pichet Kluncheun, which was performed in various cities in the UK.

Currently, he is the permanent lecturer in Performing Arts at Chiang Mai University.

頂いたサポートは、打ち合わせ時のコーヒー代として、私たちの創作活動の励みとなります。 Your support supplies our team with an extra cup of coffee to boost creative energies. Thank you!