読書ノート:Part II/Chapter 6 of THE PSYCHOLOGY OF TOTALITARIANISM

はじめに

このノートは、The Psychology of Totalitarianism(Mattias Desmet著)を読み、重要と思われた部分を抜き出して記録したものです。ノートは、章単位の構成となっています。他章のノートを参照する場合、各ノート末の「全体校正」のリンクを参照してください。

このノートは、一読者としての印象を部分的に抜き出たものです。私の意見・感想は含まれていません。しかし、部分的な抜き出しなので、正しい内容を反映していないかもしれません。また、本文での引用情報も含まれていません。従って、本書を正しく理解するためには、ぜひ原文をお読みください。

(しかし、いつの間にか、ほぼ全文を訳し始めているのですが。。。。抜き出すより、その方が楽だったので。。。。)

このノートの目的は、自分としての理解の整理ですが、もし、本書の興味の一助になれば嬉しいです。

Part II: Mass Formation and Totalitarianism /

Chapter 6: The Rise of the Masses

“Enlightenment is man’s release from his self-incurred tutelage. Tutelage is man’s inability to make use of his understanding without direction from another … ‘Dare to think! Have the courage to make use of your own reason!’ is therefore the motto of the Enlightenment.” (Immanuel Kant)

『啓蒙とは、人が自分自身で施した教育から開放されることです。誰かの保護を受けるということは、他人からの指示がなければ、自分の理解・能力を利用できない、ということです。「敢えて考えよう。自分の理性を活用する勇気を持とう。」が啓蒙のモットーです。』(エマニュエル・カント、1789年)

With these words in 1784, the great German Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant summarized what he considered the essence of the Enlightenment tradition. A century and a half later, however, a horrifying phenomenon unfolded: The Enlightenment had led to the exact opposite of what Kant envisioned. “Science” had given rise to stories that were frankly absurd; people nonetheless went along with them in blind enthusiasm and fanaticism, with little ability for critical reflection, even up to the point of radical self-destruction.

ドイツの啓蒙主義哲学者エマニュエル・カントは、啓蒙主義の本質を、この言葉で要約しました。しかし、約150年後、恐ろしい現象が広まりました。啓蒙主義は、カントが考えていたものと、正反対のものをもたらしました。「科学」は、率直に言って馬鹿げた物語を生み出しました。それにも関わらず、人々は、盲目的な熱意と狂信を伴って、それについて行きました。そこには、批判的に反応する能力が僅かしか無く、過激な自己破壊にさえ至りました。

In Germany, a race theory, propagated by a fanatical demagogue, propelled a large part of the population into a curious state of mind. People denounced relatives, friends, and colleagues who, in their opinion, were not unconditionally loyal to the German People and its leader; they accepted that fellow human beings with physical impairments be exterminated like vermin; they nodded in agreement when the Führer deemed the elimination of every German with heart and lung problems to be necessary in the long term; they agreed, overtly or covertly, with the industrialized annihilation of “inferior races.”

ドイツでは、狂信的なデマゴーグとして広められた人種理論が、多くの国民の興味を引きました。人々は、ドイツ国民とその指導者への無条件の忠誠を果たさない親戚・友人・同僚を非難・誹謗しました。彼らは、身体に障害を持つ仲間を、害虫のように排除することに同意しました。彼らは、「総統」の考え(=肺と心臓に問題のあるドイツ人を長期的に排除すべき)に同意しました。彼らは、「劣った人種」を工業化された方法で絶滅することに、公然とまたは密かに同意しました。

In Russia, an equally “scientific” story led to the same fanatical ecstasy: The whole “historical-materialist process” would focus on the creation of a society without private property, in which “the proletariat” would have the power. This also required a fair bit of extermination. At first, this took place according to a certain “logic”; at a later stage, everybody randomly fell prey to it. Tens of millions of people were deported to the gulags, where the majority of people perished. Half of the members of the communist party were also eventually liquidated, usually without the slightest hint of sedition or treason. And the most astonishing thing of all was that most victims made no effort whatsoever to refute the mostly unfounded allegations. They even made unequivocal admissions of guilt and willingly went to the gallows.

同様に、ロシアでも「科学」は、狂信的な熱狂を生み出しました。「歴史的・唯物的プロセス」は、私有財産のない社会を生み出し、そこでは「プロレタリアート」が権力を握ると、考えられました。これも、かなりの「絶滅」が必要でした。最初、この「絶滅」は、特定の「論理」に従って行われましたが、最後には、全ての人がランダムに餌食となりました。数千万人の国民が、強制収容所へ追放され、大部分の人が死にました。共産党員の半数が、反逆の兆候や証拠も無しに、最終的には粛清されました。最も驚くべきことは、ほとんどの被害者が、理由の無い嫌疑に対して反論しなかったことです。彼らは、有罪を認め、自ら絞首台へ行きました。

The first half of the twentieth century saw the emergence of Nazism and Stalinism, a completely new form of government commonly referred to as totalitarianism. It is immediately distinguishable from democracies by its oneparty structure and its disregard for basic democratic principles, such as the right to free speech and self-determination. However, the totalitarian state also radically differs from dictatorial forms of government, both in its structure (its internal organization) and in its dynamics (its process-oriented progression). In her monumental book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt situates the essence of this difference at a psychological level. While dictatorships are essentially based on instilling a fear of physical aggression—the population is struck by such a degree of fear that the dictator (or the dictatorial regime) is able to unilaterally impose a social contract—the totalitarian state is grounded in the social-psychological process of mass formation.

20世紀前半、ナチズムとスターリン主義が台頭しました。これらは、全体主義という全く新しい政治形態でした。この政治形態は、一党独裁と民主主義の原則(言論の自由や自己決定の権利)の無視により、民主主義と簡単に区別できます。しかし、全体主義国家は、構造(内部組織)とダイナミックス(プロセス志向)の点から、独裁国家と全く異なります。ハンナ・アーレントは、彼女の著書「全体主義の起源」(The Origins of Totalitarianism)にて、本質的な違いを心理的なレベルと位置づけました。独裁は、物理的な攻撃の恐怖を植え付けることに基づいています。国民は圧倒的な恐怖を植え付けられるので、独裁者や独裁政権は一方的に社会契約を強制できます。一方、全体主義国家は、大衆形成の社会心理的プロセスに基づいています。

We have to take this process into account in order to understand the astounding psychological characteristics of a totalitarian population: the willingness of the individuals to blindly sacrifice their personal interests in favor of the collective, radical intolerance of dissident voices, a paranoid informant mentality that allows government to penetrate the very heart of private life, the curious susceptibility to absurd pseudo-scientific indoctrination and propaganda, the blind following of a narrow logic that transcends all ethical boundaries (making totalitarianism incompatible with religion), the loss of all diversity and creativity (making totalitarianism the enemy of art and culture), and intrinsic self-destructiveness (which ensures that totalitarian systems invariably annihilate themselves in the end).

全体主義下の国民の心理的特徴を理解するためには、そのプロセスを考える必要があります。それは、集団のために個人の利益を盲目的に犠牲にする、個人の意思です。反対意見に対する極端な不寛容さ。政府が個人の私生活に介入することを可能にする、偏執的な情報提供者。疑似科学的の教化とプロパガンダに対する興味と感化されやすさ。全ての倫理的な境界を超越してしまう、狭い論理に対する盲目的な追従(全体主義と宗教を両立させない)。あらゆる多様性と創造性の喪失(全体主義を芸術と文化の敵にする)。本質的な自己破壊(全体主義システムが最終的に消滅することを保証する)。

An analysis of the psychological process of totalitarianism is extremely relevant in the twenty-first century. There are several signs that a new kind of (technocratic) totalitarianism is on the rise: an exponential increase in the number of intrusive actions by security agencies (opening mail, searching IT systems, installing eavesdropping devices, tapping telephones); the general advance of surveillance society; the increasing pressure on the right to privacy (especially since 9/11); the sharp increase in the last decade in citizens snitching on one another through government-organized channels; the increasing censorship and suppression of alternative voices, in particular during the coronavirus crisis; loss of support for basic democratic principles; and the introduction of an experimental vaccination program and QR code as a condition for having access to public spaces, and so on. The moment Arendt had anticipated in 1951 seems to be rapidly approaching: the emergence of a new totalitarian system led, not by “ring leaders” like Stalin and Hitler, but by dull bureaucrats and technocrats.

21世紀になっても、全体主義の心理的プロセスの分析は、とても重要です。新しい種類の(テクノクラートな)全体主義が台頭しつつある兆候があります。セキュリティ機関による侵入行為(メール開封、情報システムのスキャン、盗聴装置の設置、電話の盗聴)の指数的増加。監視社会の進展。プライバシーの権利に対する圧力(911以降)。政府が準備したチャネルを使った市民同士の密告件数の急増。検閲の増加と異なる意見への抑圧(特にコロナ・ウィルス危機の間)。民主主義の原則に対する支持の喪失。公共アクセスの必要条件としての実験的な予防接種とQRコード導入など。アーレントが1951年に予想したことが、急速に近づいている様に見えます。新しい全体主義は、ヒットラーやスターリンの様な「首謀者」によってではなく、官僚とテクノクラートによって出現します。

In the first five chapters of this book, I described how the emergence of the mechanistic worldview brought society into a specific psychological condition over the past centuries. Society was increasingly gripped by a fanatical, mechanistic ideology that degenerated into dogma and blind belief (chapter 1); experiences of meaninglessness and social isolation increased hand over fist (chapter 2); hopes were increasingly placed on a utopian, technological solution to the problems inherent in human existence (chapter 3); public space was increasingly dominated by a pseudoscientific discourse of numbers, data, and statistics that completely blurred the line between scientific facts and fiction (chapter 4); and epidemic fear and uncertainty made the population yearn for absolute authority (chapter 5). In the present chapter, I’ll describe how, from here, the socially fragmented population suddenly reunites into a unit through the process of mass formation.

本書の最初の5つの章では、機械的世界観の出現が社会に特定な心理状態をもたらしたことを説明しました。第1章:狂信的かつ機械論的なイデオロギーに掌握された社会は、ドグマと盲目的な信念へ衰退しました。第2章:自分の無意味さと社会的な孤立の経験が、増々増えました。第3章:人間固有の問題に対して、技術的な解決に期待が寄せられました。第4章:数字・データ・統計を用いて、科学的事実とフィクションの境界が曖昧になった疑似科学の言説が、増々世論の主流となっています。第5章:感染の恐怖と不安により、国民が絶対的な権威を切望しています。本章では、社会的に断片化された国民が、大衆形成を通じて、一つのグループとして再結合することについて述べます。

* * *

A crowd is a specific kind of group. Its distinguishing feature is a far- reaching “uniformization” of individuals. In the crowd, everyone becomes equal to everyone else, people think together, and they tend to identify with the same ideals. Gustave Le Bon—the French sociologist and psychologist who published one of the most important works on mass formation, Psychologie des foules in 1895—argued that the “individual soul” in the masses is completely taken over by the “group soul.” This uniformization is accompanied by an almost absolute loss of rational thinking and the ability for critical reflection, even among people who, under “normal circumstances,” are extremely intelligent and capable of well-founded criticism. It is also accompanied by a strong tendency to surrender to impulses that, under normal circumstances, would be considered radically unethical.

「群衆」とは、特定の種類のグループです。その特徴は、広範囲にわたる個人の「均一化」(uniformization)です。ギュスターヴ・ル・ボン(大衆形成に関して最も重要な研究を「Psychologie des foules」として発表したフランスの社会学者・心理学者)は、「均質化」を『大衆の「個人の魂」(individual soul)が「集団の魂」(group soul)に乗っ取られることだ』と述べました。この「均一化」は、合理的思考と批判的反省のほぼ完全な喪失を伴います。しかも、通常の状況下において、非常に知的で批判精神に富む人にさえ、この喪失は起きます。さらに、「均一化」は、通常の状況下では非倫理的と考えられる衝動に屈する強い傾向をも伴います。

Mass formation is as old as humanity itself and has appeared in many different forms. Historical examples bear witness to this diversity: the short-lived mass formation during Saint Bartholomew’s night as opposed to the longterm mass formation of the French Revolution; the totally unstructured mass of the dancing plague in Strasbourg as opposed to the organized masses we find in the army and church; the religious masses of the Crusades as opposed to the pseudoscientific masses of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries; the gigantic masses of Nazism and Stalinism; the small-scale mass formation that occurs time and again in trial juries, and so on.

大衆形成は、人類そのものと同じぐらい古く、様々な形で現れてきました。歴史が、その多様な大衆形成の形態を示しています。フランス革命の長期的な大衆形成に対して、サン・バルテルミの短期的な大衆形成。軍隊や教会の様な組織化された大衆に対して、「踊りのペスト」(the dancing plague)に見られる完全に非構造化された大衆。20世紀と21世紀の疑似科学的大衆に対して、十字軍の宗教的大衆。ナチズムとスターリン主義の巨大な大衆。何度も裁判の陪審員で起きる小規模な大衆形成。などなど。

This last example, the mass formation that occurs in trial juries, is interesting because its small scale allows for a detailed investigation. Time and again, it appears that juries, in their final verdict, are hardly (or not at all) influenced by the argumentative qualities of a plea. An attorney who delivers a perfectly fact-based and rationally structured message will have little effect. Juries are almost exclusively susceptible to frequent repetition of simple emotional messages and poignant visual images (including numbers presented in graphs). Think of all the successful trial lawyers: This is exactly how they build their plea.

最後の例(陪審員でおきる大衆形成)では、小規模なので詳細な調査ができるため、興味深いです。最終的な評決において、陪審員は、嘆願の理屈っぽい性質の影響を受けにくい(または全く受けない)ように見えます。もし、弁護士が事実に基づいた合理的な主張をしても、あまり効果はありません。陪審員は、繰り返される単純で感情的なメッセージと心に訴える視覚イメージ(グラフで表現される数字を含む)の影響を受けます。裁判で成功した全ての弁護士について考えてください。この方法が、彼らの嘆願書の作成方法です。

Masses have been around since time immemorial, but Le Bon noted that, beginning in the nineteenth century, they steadily gained momentum. Where they used to have only a short-lived influence that was curtailed and suppressed by the leaders of society, they became steadily more persistent and influential in policy making during and following the Enlightenment. This prompted Le Bon in 1895 to warn that the masses could take hold of society, leading to the emergence of a new form of governance. Le Bon was not devoid of prophetic gifts, as this is exactly what happened thirty years later with the rise of totalitarian states in the twentieth century.

大衆は大昔から存在しました。しかし、ル・ボンは、19世紀から大衆の勢いが増していることを指摘しました。それまでの大衆は、指導者の抑圧により短期間な影響力しか持てませんでした。啓蒙時代以降、大衆は、政策に対して、より粘り強く影響与えるようになりました。1895年に、ル・ボンは、大衆が社会を掌握し、新しい政治形態が生まれる可能性を警告しました。この警告は、30年後の20世紀の全体主義の台頭を正確に言い当てています。

* * *

Where did this intensification of mass formation come from? It was a logical consequence of the effects of rationalization and mechanization of the world, as discussed in the previous chapters. More and more people entered a condition of social atomization and as soon as their numbers exceed a critical limit, the process of mass formation begins. Mass formation is a complex and dynamic phenomenon that can be compared to the way convection patterns arise in water or gas when they are heated up. In the first instance, the heat in individual water molecules rises, but the molecules are not yet moving. Then small, moving patterns, which quickly disappear, emerge locally. Subsequently, increasingly larger and more durable patterns occur. Finally, we see patterns that permanently set most of the water into motion. In doing so, the convection patterns completely change the behavior of the individual water molecules, bringing them into a completely new state of motion. In the same way, mass formation brings individual people into a new psychological “state of motion.” And just as with convection patterns in water and gas, these patterns are small and short-lived at first. At a later stage, they set larger and larger societal “volumes” in motion over a longer period of time. The medieval mass formations were mostly local and ephemeral in nature; the mass formations of the French Revolution were already larger in scale and lasted a little longer; those of Stalinism and Nazism were much more significant and a lot more enduring. With the coronavirus crisis, we have, for the first time in history, reached a point where the entire world population is in the grip of a mass formation over a prolonged period of time.

大衆形成の強化は、どこから来たのでしょうか?それは、世界の合理化と機械化の影響による論理的な帰結でした。より多くの人が「社会の原子化」(social atomization) の状態になり、その数が限界を超えると、大衆形成のプロセスが始まります。大衆形成は複雑で動的な現象です。このプロセスは、加熱された水やガスの対流パターンに例えることができます。最初、個々の水分子の温度が上がりますが、水分子はまだ動きません。その後、すぐに消えてしまう「動きのパターン」が、局所的に発生します。続いて、より大きく、より長くと持続するパターンが増えます。最後に、水を恒久的に動かすパターンが発生します。この対流パターンは、個々の水分子の振る舞いを完全に変え、新しい「運動状態」(state of motion)に移行させます。同じ様に、大衆形成は、個人を新しい心理的な「運動状態」(psychological state of motion)に移行させます。水やガスの対流と同様に、大衆形成における最初のパターンは小さく短命です。後の段階で、大衆形成のパターンは、より大きな社会的「規模」を、より長期間動かします。中世の大衆形成は、ほとんどが局所的かつ一時的なものでした。フランス革命の大衆形成は、規模が大きく、少しだけより長く続きました。スターリン主義とナチズムでは、遥かに重大で、遥かに恒久的でした。コロナ・ウィルス危機により、大衆形成は、歴史上初めて、全世界の人を長期間巻き込んでいます。

(訳者追記:atomizationに関しては、第2章最後のパラグラフにて、この用語を作ったハンナ・アーレントの定義が書いてあります)

* * *

There are four conditions in particular that have to be present in a society for large-scale mass formation to occur. These four conditions were present prior to the rise of Nazism and Stalinism, and they are also present now. I’ve already mentioned them as consequences of the mechanistic ideology. I’ll summarize them again below.

大規模な大衆形成が起きるためには、4つの特別な条件が必要です。これら4つの条件は、ナチズムやスターリン主義以前にも存在しましたし、現在も存在します。これらについては、機械的イデオロギーの結果として、既に言及しました。以下で、それらを改めてまとめます。

* * *

The first condition is generalized loneliness, social isolation, and lack of social bonds among the population. The Enlightenment is characterized by an emergence of this phenomenon, but today the scale has grown to such an extent that the US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy began referring to it as the loneliness epidemic, and Theresa May in Great Britain actually appointed a Minister of Loneliness. Not insignificant to my argument, loneliness is strongly associated with the use of social media and communication technology. (Remember the effect of digitalized conversations, which I covered in chapter 3.) The problem is greatest in industrialized countries, those that are most firmly in the grip of mechanistic ideology. About 30 percent of people living in these countries report chronic experiences of loneliness and isolation, and this percentage is increasing every year. I refer to Arendt who argued that this first condition is the most important: “The chief characteristic of the mass man is not brutality and backwardness, but his isolation and lack of normal social relationships.”

第1の条件は、一般化された孤独・社会的孤立・国民同士の絆の欠如です。これを生み出したのは啓蒙主義ですが、今日その規模が大幅に拡大しました。本書の議論にとって重要ではありませんが、孤独は、SNSやネットワークの利用と強く関連しています(第3章で述べた、デジタル化された会話の効果を思い出してください)。この問題は、機械的イデオロギーに支配されている、工業国が最も大きいです。工業国に住んでいる人の30%が、慢性的な孤独と孤立を経験しています。しかも、その割合は毎年増加しています。第1の条件が最も重要である、と主張したアーレントの言葉を引用します:「大衆の主な特徴は、残忍性や後進性ではなく、通常の社会関係の欠如と孤立です。」

This deterioration of social connectedness leads to the second condition: lack of meaning in life. This second condition follows mainly from the first. Man, as a social being par excellence, lives for the Other. Remove the bond with the Other and he will experience his life as meaningless (whether he sees the connection with his loneliness or not). For instance, I describe in chapter 2 how industrialization removed meaning from work, in part by breaking the connection between the person who produces something and the person for whom it is intended. Moreover, the mechanistic worldview also led to meaninglessness in a more direct way: the machine of the universe, as well as the person-machine who is stuck in it, runs without purpose or meaning. The material particles interact with each other according to the laws of mechanics, but they have no intention whatsoever. Viewing life through this lens, whether justified or not, renders life meaningless. The phenomenon of bullshit jobs (see chapter 2) is perhaps the best illustration of this: In the second decade of the twenty-first century, half of the people were of the opinion that their job was meaningless. A 2013 Gallup World Poll found that only 13 percent of people worldwide were truly engaged in their job; 63 percent said they were not engaged (they “sleepwalk through their work and may put time into it, but are not passionate about their job”); and 24 percent are actively disengaged, meaning they actively demoralize and demotivate their colleagues. This is very significant.

社会的な絆の劣化が、第2の条件を生みます:それは、人生の意味の欠如です。第2の条件は、第1の条件から生じます。人は、卓越した社会的生き物として、他者のために生きています。他者との絆がなくなると、人は自分の人生を無意味だと感じます。本人が、孤独との関連性を知っているか否かは関係ありません。例えば、第2章で、工業化が仕事から「働くことの意味」を奪うことを説明しました。奪われるものには、「何かを生産する人」と「それを使ってもらう人」との「人間関係」が含まれています。さらに、機械的な世界観は、より直接的な方法で「人生の無意味さ」を与えます。機械的な宇宙は、目的も意味もなく動きます。そして、そこに閉じ込められた機械的な人間も同じです。物質の粒子は力学の法則に従って総合作用するが、そこには、いかなる意図もありません。このレンズで人生を覗くと、無意味さを見てしまいます。第2章で言及した bullshit jobs 現象は、これを最もよく表しています。21世紀の20年間では、半数の人が、自分の仕事は無意味だと考えていました。2013年のギャラップ世界世論調査は、世界人口の13%だけが、自分の仕事に真剣に取り組んでいたことを示します。63%は、真剣ではないと答えました。彼らは、夢遊病のように仕事をし、もし時間を割いても、傾ける情熱はありません。24%は積極的に disengage していると答えました。つまり、彼らは、積極的に同僚の士気をくじき、やる気を奪っています。これは大変に深刻なことです。

The third condition is the widespread presence of free-floating anxiety and psychological unease within a population. Free-floating anxiety is a form of anxiety that is not image-bound, in contrast to anxiety that is imagebound (for example, fear of thunder, snakes, war). Such anxiety is mentally difficult to manage and presents the constant risk of turning into panic, which is perhaps the most aversive psychological state for human beings. For that reason, a person in that state seeks to link their anxiety to an object. Free-floating anxiety can be traced back to the first two conditions. A person who has lost his bond with the Other and does not feel meaning typically experiences an indefinable unease and anxiety. This condition has been strongly present in the first decades of the twenty-first century. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that one in five people worldwide has been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. These numbers are striking, all the more so because they are likely an underestimation. And the incidence of mental suffering in general, including the cases that go undiagnosed, is of course even higher. This can, amongst others, be concluded from the enormous consumption of psychotropic drugs. In a small country like Belgium, with eleven million inhabitants, no fewer than three hundred million (!) doses of antidepressants are taken every year.

第3の条件は、国民内に広がった、「漠然とした不安」(free-floating anxiety)と心理的な不安(psychological unease)です。漠然とした不安は、雷や蛇は戦争のような具体的なイメージに縛られていない、不安の一種です。漠然とした不安は、精神的に対処することが難しく、パニックになるリスクが常にあります。パニックは、人間にとって最も嫌悪な精神状態です。故に、この状態にある人は、自分の不安と関係すると思われる「何か」を探します。漠然とした不安は、第1条件と第2条件へ遡ることができます。他者との絆を失い、人生の意味を感じなくなった人は、原因不明の不安を経験します。この状態は、21世紀の最初の10年間に強く現れました。例えば、世界保健機関は、世界中の5人に1人が、不安障害と診断されたと報告しました。これらの数字は印象的ですが、過小評価されているかもしれないので、もっと大きい可能性があります。そして、一般的な精神的苦痛の発生は、診断されなかったケースを含むと、更に高くなります。この論考は、向精神薬の膨大な消費から裏付けられます。人口1100万人のベルギーで消費される抗鬱薬は、毎年3億回分です。

The fourth condition, in turn, also follows from the first three: a lot of free-floating frustration and aggression. The link between social isolation and irritability is logical and has also been established empirically. People perturbed by loneliness, lack of meaning, and indefinable anxiety and unease generally feel increasingly irritable, frustrated, and/or aggressive and look for objects to take these feelings out on. The sharp increase of racist and threatening language on social media during the last decade (tripling between 2015 and 2020, see chapter 5) is a striking example. What accelerates mass formation is not so much the frustration and aggression that are effectively vented, but the potential of unvented aggression present in the population—aggression that is still looking for an object.

第4条件は、最初の3つの条件に従います。多くの、漠然としたフラストレーションと攻撃性です。社会的な孤立とイライラの関係は論理的であり、経験的にも確立されています。孤独、人生の無意味さ、漠然とした不安に狼狽させられる人は、イライラやフラストレーションを感じ(時には攻撃的になり)、この感情を吐き出すための対象を探します。過去10年間のSNSにおける人種差別や脅迫の急増(2015年から2020年の間に3倍、第5章を参照)は、わかりやすい例です。大衆形成を加速するのは、効果的に吐き出されるフラストレーションや攻撃性ではなく、国民の中に潜在的に溜まっている攻撃性です。つまり、攻撃対象を探している「攻撃性」です。

* * *

How exactly do these conditions lead to mass formation? The catalyst for mass formation is a suggestion in the public sphere. If, under the aforementioned circumstances, a suggestive story is spread through the mass media that indicates an object of anxiety—for example, the aristocracy under Stalinism, the Jews under Nazism, the virus, and, later, the anti-vaxxers during the coronavirus crisis—and at the same time offers a strategy to deal with that object of anxiety, there is a real chance that all the free-flowing anxiety will attach itself to that object and there will be broad social support for the implementation of the strategy to control that object of anxiety.

上述した4つの条件は、どのようにして大衆形成につながるのでしょうか?大衆形成の引金は、公共圏(public sphere)への示唆です。前述した4つの条件が成立している状況で、不安の対象(例えば、スターリン主義下の貴族、ナチズム下のユダヤ人、ウィルス、その後の反ワクチン派 - anti-vaxxersa - などです)と、その対象への対処戦略を示唆する物語がマスメディアなどで流布されると、全ての漠然とした不安が示唆された対象と紐づき、その対処戦略に対する幅広い社会の支持を得られます。

This process yields a psychological gain. Firstly, the anxiety that previously roamed through society as a tenebrous fog is now linked to a specific cause and can be mentally controlled via the strategy put forward in the story. Secondly, through a common struggle with “the enemy,” the disintegrating society regains its coherence, energy, and rudimentary meaning. For this reason, the fight against the object of anxiety then becomes a mission, laden with pathos and group heroism (for example, the Belgian government’s “team of 11 million” going to war against the coronavirus). Thirdly, in this fight all latent brewing frustration and aggression is taken out, especially on the group that refuses to go along with the story and the mass formation. This brings an enormous release and satisfaction to the masses, which they will not let go of easily.

このプロセスは、心理的な利益をもたらします。第一に、社会に漂っている暗い霧だった不安が特定の原因と結びつき、提示られた戦略により不安を心理的に制御できるようになります。第二に、共通の敵との闘争を通じて、崩壊しつつある社会が一貫性と活力と基本的な意味を取り戻します。これにより、不安対象に対する戦いは、情緒的かつグループ英雄主義に満ちた使命となります。ベルギー政府の「team of 11 million」キャンペーンは、その一例です。第三に、潜在的に醸芳されているフラストレーションと攻撃性は、この物語と大衆形成に同意しないグループに向けられることにより、取り除かれます。これは、大衆に大きな開放感と満足をもたらすので、大衆はこれを簡単には手放しません。

Through this process, an individual pivots from a highly aversive and painful psychological state of social isolation to the maximum interconnectedness that exists among the masses. This creates a kind of intoxication, which is the actual impetus to go along with the mass- forming narrative. In the prolonged mass formations that led to the rise of the totalitarian states, this intoxication was often merely latent but sometimes fully manifests itself overtly. Think, for example, of a crowd that sings together or chants slogans in a football stadium, for instance. The voice of the individual dissolves into the overwhelming, vibrating group voice; the individual feels supported by the crowd and “inherits” its vibrating energy. It doesn’t matter what song or lyrics are sung; what matters is that they are sung together. An equivalent to this exists on a cognitive level: What one thinks does not matter; what counts is that people think it together. In this way, the masses come to accept even the most absurd ideas as true, or at least to act as if they were true.

このプロセスを通して、個人の気持ちは、社会的孤立による心理的苦痛と強い嫌悪感から、大衆間の最大限の相互関係に切り替わります。これは、ある種の酩酊感を生み出します。この酩酊感は、この大衆形成に伴う物語と共に歩むための動機となります。全体主義の台頭につながる長期間の大衆形成において、この酩酊感は、しばしば潜在的ですが、時々、表に現れます。例えば、サッカースタジアムで一緒に歌ったり、スローガンを唱える群衆を考えてください。個人の声は、圧倒的なグループの振動する声に溶け込みます。個人は群衆に支えられていると感じ、群衆の振動を受け継ぎます。そこで、どんな曲や歌詞が歌われているか、は問題ではありません。重要なのは、それを全員で歌っていることです。これと同じことが、認知レベルで存在します:「考える内容」は重要ではありません。重要なのは、人々がそれを「一緒に考えている」ことです。このようにして、大衆は、たとえそれが最も馬鹿げた考えでも、それを真実として(または、あたかも真実で有るかのように)受け入れます。

* * *

The essence of mass formation amounts to the following: A society saturated with individualism and rationalism suddenly tilts toward the radically opposite condition, toward radically irrational collectivism. To put it in Nietzschean-classical terms: Dionysus, in one fell swoop, overthrows the dictatorship of Apollo and seizes power in society. This is also immediately apparent from the following: In all major mass formations, the main argument for joining in is solidarity with the collective. And those who refuse to participate are typically accused of lacking solidarity and civic responsibility. This is one reason why the absurd elements in a story do not matter to the masses: The masses believe in the story not because it’s accurate but because it creates a new social bond.

大衆形成の本質は、以下と等しいです:個人主義と合理主義で飽和した社会は、突然、正反対の状態、つまり不合理な集産主義(collectivism)、に傾きます。ニーチェの古典を用いると:「ディオニソスは一気にアポロンの独裁政権を倒し、社会の権力を掌握する」。このことは、以下からも明らかです。全ての主要な大衆形成において、参加する主な理由は、集団との連帯です。そして、その参加を拒否する人々は、連帯および市民的責任の欠如として非難されます。大衆にとって、物語中の不合理な部分は重要ではありません。大衆がその物語を信じるのは、それが正確だからではなく、新しい社会的な絆を作るからです。

The strategy of dealing with the object of anxiety fully accomplishes the purpose of a ritual. The function of ritualistic behaviors is to create group cohesion. It is a symbolic behavior that aims to subject the individual to the group. As such, it must ideally have as little practical use as possible and require sacrifice on the part of the individual. Think of the ritual sacrifices of food, animals, and humans in primitive societies. That is exactly why the absurdity of the coronavirus measures does not encounter any resistance from part of the population. In a sense, the more absurd and demanding the measures are, the better they will fulfill the function of a ritual and the more enthusiastically a certain part of the population will go along with it. Think, for example, of the fact that some people wear a mask when driving, even if they are the only person in the car. The ritual function of mass behavior is always present. The experts in the coronavirus crisis have also been more or less aware of this. At times, they let it slip that the measures actually have hardly any practical use. In March 2020, an expert virologist stated on Belgian national television that the lockdowns would barely reduce the number of deaths; 23 in August 2020, an expert virologist suggested that the face masks have a largely symbolic function; 24 in October 2020, the health minister of Belgium said the same about the closure of bars and restaurants (implying that countless people saw their livelihood ruined for symbolic reasons). 25 The message is clear: The individual must at all times show that he submits to the interest of the collective, by performing self-destructive, symbolic (ritualistic) behaviors.

不安対象に対処する戦略は、儀式の目的である「集団の結束を生み出すこと」と完全に合致します。儀式とは、個人を集団に服従させるための象徴的な行動です。儀式は、実用的な部分を限りなく小さくし、個人の犠牲を要求します。原始社会における生贄(食べ物、動物、人)の儀式を考えてください。だからこそ、コロナ・ウィルス対策の不合理さに対して、国民の一部から、いかなる抵抗もありませんでした。ある意味で、対策が、より不合理かつ厳しいほど、儀式としてより機能し、ある特定一部の国民は熱心に従います。1人で車を運転しているにも関わらずマスクをするのは、この例です。大衆行動の儀式的機能は、常に存在します。コロナ・ウィルス危機における専門家も、多かれ少なかれ、このことに気づいていました。時々、彼らは、対策に実用性が無いと、うっかり口を滑らせます。2020年3月、ウイルス学の専門家がベルギーの国営放送で「封鎖しても死亡者数はほとんど減らない」と発言しました。2020 年 8 月 23 日、ウイルス学者は、フェイス マスクの主な機能は、その象徴性にあることを示唆しまし。2020 年 10 月 24 日、ベルギーの保健大臣は、バーやレストランの閉鎖について同じことを述べました。つまり、無数の人が、象徴的な理由で生活を破壊されていることを意味します。メッセージは明確です:個人は、自己破壊的で象徴的な(儀式的な)行動によって、常に集団の利益に服従していることを、示さねばなりません。

Ultimately, the reasons individuals participate in mass formation are rarely, if ever, rational in nature. The justification of the strategy is promoted by experts with fancy titles, often on national television, making it seem like a given measure is generally accepted. For many people, this suffices as proof of correctness of the measures: “Surely the experts know what they’re doing.” “Surely, they can’t all be wrong.” “They obviously wouldn’t say it if it weren’t true?” And so on. In other words, the argumentum ad populum (appeal to popularity) and the argumentum ad auctoritatum (appeal to authority), known as logical fallacies since ancient times, are enough for most people to accept the story. In everything, you feel that the underlying motivation to go along with the story is the group formation and the group pressure, not the accuracy of the story.

個人が大衆形成に参加する理由が合理的であることは、極めて稀です。派手な肩書をもつ専門家(しばしば国営テレビ)が、「ある対策が一般的に受け入れられている」様に見せることで、大衆形成の戦略は行われます。多くの人にとって、この宣伝方法は、対策の正しさの証明として十分です:「専門家は、何をしているのかを、ちゃんと知っている」、「それらの全てが間違っているわけではない」、「もし、その対策が間違っていたら、専門家はそんなことを言わないはずだ」などなど。古くから知られている論理的誤謬である、「衆人に訴える論証」(the argumentum ad populum)と「権威に訴える論証」(the argumentum ad auctoritatum)は、大部分の人にとって、物語を受け容れるための十分な理由になります。全てにおいて、この物語に従うという動機は、物語の正確さではなく、グループの形成とグループによる圧力です。

* * *

The well-known conformity experiment by Solomon Asch demonstrates in a very convincing way the enormous impact of mass formation on individual judgment. Asch conducted his experiment shortly after World War II. He did so in an effort to understand how the often-absurd theories of Nazism and Stalinism gained such a strong grip on the population and sought to gain insight into the psychological mystery of mass formation and totalitarianism.

有名なソロモン・アッシュの同調実験は、大衆形成が個人の判断力に大きな影響を与えることを、説得力のある方法で示しました。彼は、第二次大戦直後に、この実験を行いました。彼がこの実験をした理由は、ナチズムやスターリン主義の馬鹿げた論理が国民を強く捉えた理由とともに、大衆形成と全体主義の心理的な謎への洞察を得るためでした。

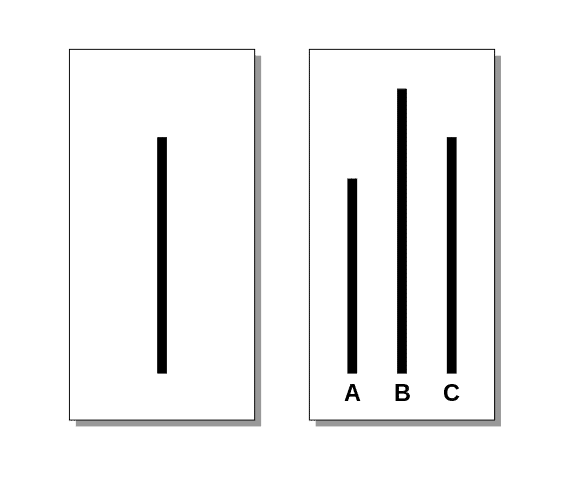

Take a good look at figure 6.1. Which of the segments A, B, and C has the same length as line 1? That was the question Asch asked the participants of his conformity experiment. Each group of eight test subjects included seven of Asch’s employees, all of whom had been instructed to answer “line segment B” without blinking an eye. The eighth participant, the only genuine test subject, usually gave the same answer as the seven persons before him. Only 25 percent consistently stated what even a blind person could see: Not line B but line C has the same length as line 1. After the experiment, some test subjects said that they did know the correct answer but did not dare go against the group. Even more interestingly, others admitted that they had started to doubt their own judgment under group pressure and eventually accepted the absurd group judgment as true.

アッシュの同調実験(Wikipedia)からの引用

図6.1を見てください。線分A、B、Cのうち、左の線分と同じ長さのものはどれですか?これは、アッシュが実験の被験者に尋ねた質問でした。各グループは8名構成で、そのうちの7名はアッシュの従業員で、瞬きせずに「線分B」と答えるように指示されていました。通常、8番目の参加者(本当の被験者)は、目の前にいる他の7名と同じ答えを出します。正しい答え(線分B)を一貫して出し続けたのは、被験者全体の25%でした。実験後、数名の被験者は、正しい答えを知っていたが、グループに反対しなかった、と言いました。更に興味深いことは、その他の被験者は、グループの圧力下で自分の判断を疑い出し、最終的にはグループの馬鹿げた判断を真実として受け入れました。

These three groups are always present in mass formation. There is always a group that is in the grip of mass formation and “believes” the story (this group constitutes the totalitarized part of the population), a second group that does not really believe it but remains quiet and goes along with the masses (or at least, does not oppose them), and a third group that does not believe in the mass-forming story and also speaks or acts out against it. These three groups typically intersect with all pre-existing social groups. This is shown, time and again, in historical examples of large-scale mass formation. And it also became apparent during the coronavirus crisis. At the beginning of the crisis, new societal “camps” emerged at lightning speed, crossing all the pre-existing camps—people either went along with the virus story or not. Left or right of the political spectrum, regardless of skin color and social status, profession and hobbies: All these boundaries blurred. The only thing that counted was what people thought of the virus.

この3つのグループ(グループの考えに自分を合わせる、敢えてグループに逆らわない、自分の意見を一貫させる)は、常に大衆形成に存在します。第1のグループは、大衆形成の支配下にあり、大衆の物語を信じます。第2のグループは、大衆の物語を信じないが、黙っていることで大衆と同調します。第3のグループは、大衆の物語を信じず、それに反対する発言・行動を取ります。これら3グループは、既存の全ての社会的なグループと交差します。つまり、どこの階層や集団にも、3つのグループが存在します。これは、大規模な大衆形成の歴史で何度も現れます。そして、コロナ・ウィルス危機の際も同じでした。危機の初期、新しい社会的な「キャンプ」が電光石火の勢いで出現し、既存の全ての「キャンプ」を横断しました。人々の関心は、ウィルスの物語に賛成するか否かだけした。政治的な左右、肌の色、社会的地位、趣味・興味に関係なく。全ての境界がぼやけました。考慮されることは、人々がウィルスについて、どう考えているか?、だけでした。

Typically, these three groups are highly diverse, but for specific reasons this diversity is most visible in the group that protests loudly against the masses. In the mass itself, diversity disappears under the typical uniformizing effect of the masses (the masses make all individuals equal to everyone else) and the silent middle group does not stand out anyway, whereas the third, nonconformist group typically comes to life and all the individuals express themselves in their own specific way, which sharply highlights its diversity.

この3グループは、非常に多様です。しかし、第3グループの多様性が最も可視化されます。第1グループにおいて、多様性は、大衆の均一化効果により消えます。つまり、大衆は、全ての個人を、その他全ての人と等しくします。第2グループは、とにかく目立たないようにしています。一方、第3グループは、活気づき、全ての個人が独自の方法で自分自身を表現し、その多様性を際立たせます。

* * *

As Le Bon noted in 1895, the effect of mass formation is identical to hypnosis. Both hypnosis and mass formation are largely caused by a voice, in the literal sense—through the physical, vibrating qualities of the voice. Totalitarian leaders are well aware of this, sometimes intuitively, sometimes consciously. Totalitarian systems have always been maintained primarily by systematic indoctrination and propaganda, injected into the population on a daily basis via mass media (without mass media, it is not possible to generate such long-lasting mass formation as that which gave rise to Stalinism and Nazism). This way, the population is literally kept on the vibrational frequency of the voice of totalitarian leaders.

ル・ボンが1895年に指摘した通り、大衆形成の効果は催眠術と同じです。催眠術も大衆形成も、文字通り、声によって引き起こされます。全体主義の指導者は、このとことに気づいています。全体主義システムは、マスメディアを介して日々注入される、体系的な教化とプロパガンダによって、維持されています。マスメディア無しに、ナチズムやスターリン主義を台頭させるような長期間の大衆形成を生み出すことは不可能です。

On the one hand, the population is systematically exposed to the voice of the totalitarian leaders. On the other hand, every alternative voice is systematically eliminated. The first thing totalitarian leaders do is make sure their voices are the only ones left. To a certain extent, this is also what classical dictators do, but they limit the monopoly on the voice to the public sphere. They silence the political opposition. Totalitarian systems operate in a more thorough way. They censor alternative voices in the private sphere as well. On the one hand, this happens “spontaneously” due to a paranoid informant mentality that accompanies mass formation (which, in fact, is a result of a typical intolerance to alternative opinions, which we will discuss later). On the other hand, totalitarianism also expurgates the private sphere of alternative voices by inducing far-reaching social fragmentation and isolation. Totalitarian systems typically make it nearly impossible for people to gather in larger groups, and they strive to sever all social and family ties and replace them with the only allowable bond: the one between the individual and the totalitarian system (that is, the collective). In the Soviet Union, this process was implemented in a much more systematic way than in Nazi Germany; this is why the process of totalitarization in the Soviet Union persisted in a more far-reaching way.

国民は、全体主義指導者の声に、体系的に晒されています。一方、全ての異なる声(意見)は、体系的に排除されます。全体主義指導者が最初に行うことは、自分たちの声だけが残るようにすることです。これ自体は、古典的な独裁者も行いました。しかし、独裁者による声の独占は、公共の領域に限られます。独裁者がすることは、政治的野党を黙らせることです。全体主義システムでは、より念入りな方法を取ります。全体主義では、私的な領域で異論を検閲します。この検閲は、大衆形成に従う被害妄想的な情報提供者により、自発的に始まります。これは、異なる意見に対する不寛容さの結果です。これについては、後で議論します。さらに、全体主義は、広範囲な社会的な断片化と孤立を引き起こすことで、異なる意見のための個人的な空間が排除されます。結果として、全体主義システムは、人々が集まって大きなグループを形成することを、ほぼ不可能にします。さらに、全体主義システムは、全ての社会的・家族的絆を断ち切り、唯一許された絆に置き換えようとします。唯一の絆とは、個人と全体主義システム(つまり集団)の間の一本の絆だけです。ソビエト連邦の絆置き換えプロセスは、ナチス・ドイツよりも体系的な方法でした。これにより、ソビエト連邦の全体主義システムが、より永続的かつ広範囲でした。

To return to the similarity between hypnosis and mass formation: In both cases, a suggestive statement or a suggestive story (conveyed by a voice) focuses attention on a very limited aspect of reality. Compare it to the circle of light emitted by a lamp, which is focused and makes everything outside of this circle disappear into darkness (see figure 6.2). In addition to the ritual function of the mass behaviors, this narrowing of the field of attention is a factor that ensures the logic will extend to its absurd conclusions.

集団催眠と集団形成の類似性

に話を戻します。示唆された発言や物語は、現実の非常に限られた側面だけに注意を集中させます。ランプの光に例えると、ランプが中心に光を当てると、周辺は暗闇に隠されてしまいます(図6.2を参照)。大衆行動の儀式的機能に加えて、この「注意領域の矮小化」は、集団が支持する論理が馬鹿げた結論になることを保証しています。

For example, in the coronavirus crisis, we’ve seen a narrowing of the field of attention in the following way: People who fall victim as a result of the measures—for example, deaths due to emotional and physical neglect during the lockdowns in residential care centers, non-COVID-19 patients whose treatment was postponed, victims of domestic violence, people affected by side effects of vaccinations, and so on—receive little attention compared to COVID-19 victims, or at least they are given remarkably little weight in decision-making. Furthermore, also very striking: The collateral damage of the victims may be mentioned occasionally, but it is rarely, if ever, presented in a numerical-visual way.

コロナ・ウィルス危機では、以下の様な「注意領域の矮小化」が起きました。対策の結果として犠牲になった人々は、COVID-19の被害者と比較して、大した注意を払われませんでしたし、意思決定においても極めて小さい重み付けしか与えられませんでした。例えば、対策の犠牲者とは、ケアセンターのロックダウン中に精神的・身体的ネグレクトによる死亡、治療が延期されたCOVID-19以外の患者、対策の結果起きた家庭内暴力の被害者、予防接種の副作用に苦しんでいる人、などです。更に、印象的なのは、これら犠牲者の巻き込み被害は、時には言及されますが、数値的視覚的な方法で示されたことが、ほとんどありません。

This is crucial because, as I described in chapter 4, what’s expressed in numbers and graphs has the effect of being (wrongly) perceived as facts. As such, the psychological process of mass formation seems to ensure that mass media, almost intuitively, chooses to perpetuate the mass formation by using graphics for only the information that supports the story.

第4章へ述べた様に、数字とグラフで表現されたものは、(たとえ、それが間違っていても)事実として受け取る効果があるので、非常に重要です。大衆形成の心理プロセスでは、マスメディアが、大衆形成の物語を支持する情報だけをグラフで表現することにより、大衆形成の永続化に貢献しています。

The narrowing of the field of attention also extends to the emotional field: Victims of the pandemic response measures have elicited remarkably little empathy. For these victims, there are no daily statistics, no case descriptions, no testimonials from relatives covered in the media. Also consider a virologist’s statement that a boy who died at a so-called lockdown party deserved “zero pity.” These victims fall outside the circle of light, both cognitively and emotionally.

「注意領域の矮小化」は、感情の領域にも及びます。パンデミック対策の犠牲者は、ほとんど共感を得られませんでした。これらの犠牲者に関して、日々の統計にも、症例説明にも、メディアにも取り上げられませんでした。いわゆるロックダウン・パーティーで死亡した若者に対して、ウィルス学者が「同情はゼロ」と言ったことを考えてください。これらの犠牲者は、認知的にも感情的にも、「光の輪」(図6.2)の外側です。(訳者追記:ロックダウンのストレスから開いたパーティーで警察に追われ、逃げようとして窓から転落して死亡した21歳の青年の話)

This emotional insensitivity to suffering that falls outside of the circle of attention should not be confused with ordinary egoism. Le Bon noted that both mass formation and hypnosis enable individuals to radically ignore their self-interest, yes, even their own pain. The hypnotic story focuses attention on a small aspect of reality to such a degree that everything outside it, including one’s own pain and to a broader extent, one’s own interests, passes unnoticed. With a simple hypnotic procedure, patients can be anesthetized to such a degree that surgical incisions can be made painlessly (see chapter 10). Similarly, during the coronavirus crisis, a large part of the population accepted with remarkable ease measures that destroyed their enjoyment of life, freedom, and prosperity.

注意領域の外側にある苦しみに対して無感情になることを、通常のエゴイズムと混同すべきではありません。ル・ボンは、大衆形成と催眠術の両方は、自らの興味(利益?)を、たとえ痛みでさえも、徹底的に無視できるようになる、と指摘しました。催眠術は、現実の極めて狭い領域に意識を集中させるので、それ以外の全て(自分の痛みや、より広い自分自身の興味[利益?]にさえも)に気付きません。単純な催眠術処置で、麻酔処置ができるので、苦痛無しに外科手術が行えます(第10章参照)。同様に、コロナ・ウィルス危機の間、大部分の国民は、自分たちの生きる楽しみ・自由・繁栄を破壊する感染対策を、驚くほど簡単に受け入れました。

This was, by far, the most astonishing observation for the chroniclers of twentieth-century totalitarianism: The almost limitless tolerance for the enormous personal damage the population endured. For example, totalitarized Germans were devoutly grateful to Hitler for having a plan B in case their Great Mission would fail: death with grace—the gas chamber—for every German citizen.

この現象は、20世紀の全体主義を見てきた者にとって、最も驚くべき観察結果でした。莫大な個人的損害に対して、国民が示した(耐えた)ほぼ無限の寛容さに。例えば、全体主義化したドイツ人は、この「偉大な使命」が失敗した場合のプランBを用意したヒットラーに心から感謝しました。全てのドイツ市民に対する栄光ある死、つまりガス室に。

The phenomenon of mass formation not only has a profound impact on a cognitive and emotional level, but sometimes also on sensory perception. In some circumstances, collective hallucinations occur under the influence of mass formation, a phenomenon that challenges the understandings in modern psychology. A well-known historical example is the appearance of Saint Gregory on the city ramparts of Jerusalem, which was witnessed by a full army of crusaders. Another example, from more recent times, is the raft of drowning persons observed in broad daylight by a whole crew of marines and described by each of them in the same way, in great detail. On closer inspection, it was no more than a few branches with seaweed on them. The impact of mass formation on the mental functioning of humans is virtually unlimited. It has an impact on the individual’s experience of reality to such an extent that it is justified to ask: For an individual in the grip of mass formation, is there still a reality beyond the one created by the masses?

大衆形成の現象が影響を与えるのは、認知的・感情的なレベルだけでなく、感覚・知覚も含んでいます。ある状況下では、大衆形成の影響により、集団的な幻覚が起きます。この現象は、現代の心理学でも解明できていません。よく知られている歴史的な例として、エルサレムの城壁に聖グレゴリーが現れる現象です。十字軍のほぼ全員が目撃したことになっています。最近の例では、海兵隊全員が白昼に溺れている人の筏を目撃した事例です。全ての目撃者の説明は、細部に至まで同じでした。しかし、近づいてみると、それは海藻が付いた数本の枝でした。大衆形成が人間の精神機能に与える影響は、事実上無限大です。「大衆形成に支配された個人にとって、大衆によって作り出された現実を超える現実はあるのか?」と問えるぐらい、大衆形成は個人の現実体験に影響を与えます。

* * *

We have to add one more important characteristic to the problematic psychological properties of mass formation: radical intolerance of other opinions and a strong tendency toward authoritarianism. To the masses, dissident voices appear 1) antisocial and devoid of solidarity, because they refuse to participate in the solidarity that the mass formation creates; 2) completely unfounded, as critical arguments are not assigned any cognitive or emotional weight within the narrow circle of attention of the masses; 3) extremely aversive because they threaten to break the intoxication, and in this way confront the masses again with the negative situation that preceded the mass formation (lack of social bond and meaning, indefinable fear and unease); 4) extremely frustrating because they threaten to remove the venting of latent aggression.

大衆形成が持つ、もう一つの重大な心理的特性を、ここで加えねばなりません:それは、異なる意見に対する根本的な不寛容と権威主義への強い傾倒です。大衆にとって、反体制的な意見は、以下と映ります。1)反社会的で連帯が欠けていると考えます。なぜなら、反対者は、大衆形成が作る連帯に参加することを拒否しているからです。2)全く根拠がないと考えます。なぜなら、批判的な議論は、大衆の「矮小化された注意領域」の範囲外なので、認知的・感情的に重みづけられていないからです。3)極端に嫌悪します。なぜなら、反対者は、大衆を大衆形成前の状況(社会的絆の欠如、人生の意味の欠如、曖昧な恐怖と不安)に戻し、大衆形成が作り出す高揚感を破壊するからです。4)極度のフラストレーション。なぜなら、反対者が潜在的な攻撃性を解放させると脅しているからです。

This radical intolerance ensures that the masses are convinced of their superior ethical and moral intentions and of the reprehensibility of everything and everyone who resists them: Whoever does not participate is a traitor of the collective. Snitching is therefore commonplace; the population itself is the main branch of the secret police. Combined with the fourth factor, the opportunity mass formation offers to act out frustration and aggression without limit, this creates a well-known phenomenon: The masses are inclined to commit atrocities against those who resist them and typically execute them as if it were an ethical, sacred duty. Historical examples are the Deus lo volt (God wills it) and the Got mit uns (God with us) with which the Crusaders and the Nazis respectively committed their atrocities; the Bolshevik belief that the ultimate justice was being practiced by massacring the Romanovs and other alleged enemies of the proletariat; a butcher who, during the French Revolution, slit the throat of the defenseless (and innocent) director of the Bastille with a knife and demanded a medal for doing so; the Septemberists of the French Revolution who conscientiously ensured that all citizens were able to closely watch the executions of clergy and noblemen.

この根本的な不寛容さは、以下を正当化します:1)大衆の優れた倫理性、2)大衆の道徳的意図、3)大衆に抵抗する全ての人・ものに対する非難。参加しない人は、誰であれ裏切り者なのです。密告は当然です。国民自体が、秘密警察の主要な支部となります。この不寛容さが第4の要素(極度のフラストレーション)と組み合わさると、際限のない攻撃性を発揮し、歴史的に有名な現象を起こします。大衆は、抵抗する人々に対して、まるで倫理的かつ神聖な義務であるかの様に、残虐な行為を実行する傾向があります。ロマノフ家をはじめとする、プロレタリアートに敵対する人々を殺害することにより、 究極的な正義がなされたと信じるボルシェビキ。フランス革命で、無防備な(かつ無実の)バスティーユ所長の首を切り裂き、勲章を要求した肉屋。全ての市民が、聖職者や貴族の処刑をよく見られるようにした、フランス革命の9月革命主義者。

According to Le Bon, authoritarianism and intolerance are essential characteristics of mass formation. We also see this characteristic of mass formation steadily on the rise in coronavirus society. As the crisis continues to unfold, the dominant discourse imposes itself in an increasingly authoritarian way and censors and represses alternative voices in an ever more radical way. Publications that don’t fit with the dominant narrative are blocked on social media, even if they’ve been published in top medical journals such as The Lancet; doctors and researchers critical of coronavirus measures are fired by their institutes; in early 2021, the Belgian Order of Physicians issued a general rule that any doctor who casts doubt on the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine would be barred; from November 2021, one was no longer allowed to enter restaurants, bars, and a number of other places without a QR code, and so on. This is ultimately the difference between the solidarity of the masses and loving connectedness: The former is always at the expense of a particular group, the latter is not.

ル・ボンによれば、権威主義と不寛容は、大衆形成の本質的な特徴です。今日のコロナ・ウィルス社会でも、この特徴を見ることができます。危機が広がるほどに、支配的な言説(dominant discourse)は、ますます権威主義的になり、今までに無い徹底した方法で、他の意見を検閲し、抑圧しています。支配的な物語(dominant narrative)に合わない出版物は、トップの医学雑誌(ランセットなど)には掲載できても、SNSではブロックされます。コロナ・ウィルス対策に批判的な医師や研究者は、研究機関から解雇されます。2021年初頭、ベルギー医師会は、「全ての医師に対してワクチンの効果と安全性に疑問を呈するとを禁止する」という一般規則を発行しました。2021年11月から、QRコード無しに、レストラン・バー・その他の場所に入れなくなりました。これが、「大衆の連帯」と「愛情のある絆」の違いです。前者は特定グループを犠牲を強いますが、後者はそうではありません。

全体構成

Part I: Science and its Psychological Effects

Part II: Mass Formation and Totalitarianism

Part III: Beyond the Mechanistic Worldview

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?