書の特質としての 「身体性」、「時間性」、「自然性」

日本語訳

https://www.nakajimahiroyuki.net/translation/

書の特質とはどのようなものだろうか?

書には「造形」と「意味」があると言われる。「造形」とは作品にみられる布置や形、線質のこと。西洋美学の井島勉によれば「書は文字の美術、造形芸術の一ジャンル」であり、また書家の鮫島看山は「書は線の美、文字という素材を借りて表現する線の芸術だ」と言った。書は文字を使った造形表現であるという考え方である。

では、「意味」の方はどうか。書は文字や言葉を書く以上、そこに何が書かれているのか、その意味が問われることになる。かつて洋画家の小山正太郎は「書は文学である」と言った。書は、文字を書き付けたものであるから美術ではなく文学であるという考え方である。しかも書は、活字表記ではあらわせないたくさんの情報を文字や言葉に付与することが出来る。書きぶり中に、書き手の個性だけでなくその時の思いや感情の襞を見て取ることが出来るからである。

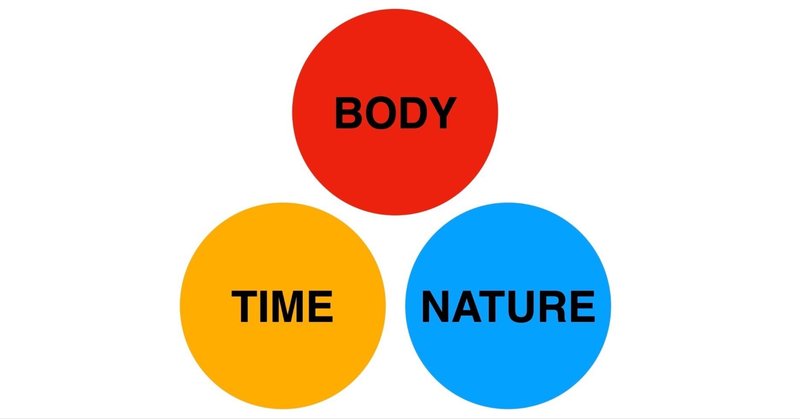

私は、書の特質としてこの「造形」と「意味」に加えて「身体」と「時間」、そして「自然」というものを考えるようになった。書とは身体の軌跡、書は自然とともにあるという視点である。私は海外での活動を通じてその意を強くした。

書と身体性

画面は床に敷かれています。私は画面と向き合うのではなく、画面の中に自ら入り込んでいきます。腰を落とし、身体を少しかがめ、間をとりつつ、手足は円弧を描きます。太極拳の動きです。頭を使って文字を書くのではありません。文字を書こうとする身体の軌跡が紙面に残るのです。

私たちはハイテクの恩恵で安楽な日常を手にするようになった。だがその一方で、自らの身体を自在に使う機会を失うことになった。

文字書きを例にとれば、かつて私たちは筆と墨で巧みに字を書いていた。その後筆記具は代わりこそすれ、手で書きしるすという行為は古代から現代まで変わらずに続いて来た。

ところがパソコンや携帯の爆発的な普及にともない、今や文字は「書く」ものから「打つ」ものへと変わりつつある。私たちが経験しているこの変化は、文字表記の長い歴史の中でもかつてない劇的な出来事である。筆と墨で文字を書くことが稀になった今、書はこれまでにない意義を持つことになった。それは書による身体性の回復、つまり書を通じて、身体を意識的に使うことを経験し、また身体に備わる力を再認識することである。

私は日本とイタリアで習字を教えているうちに、書は一種の身体術ではないかと考えるようになった。習字では手本を横に置き、出来るだけ手本の特徴を捉えるように書く。書き終えたら手本と照合して不出来なところをチェックし、さらに書き続けていく。筆運びが正しくないと、つまり身体の使い方が間違っていると、その結果が半紙の上に現れる。わざわざビデオに撮らなくても、線やかたちを見れば身体の欠点が分かる。

書の場合、一度書き始めたら後戻りは出来ないし、やり直しもきかない。最後まで意識を集中しながら、身体の動きを正確にコントロールし続けなければならない。書は一種の身体術、そう気づいてから私の指導法は身体の使い方を問うものへと変わっていった。教室では相手の筆さばきを見るのではなく、身体の動きをチェックする。フォームが正しければ、正しい結果は後からついてくる。日本人にもイタリア人にも全く同じメソッドが通用した。一方制作においてはどうか。私は頭で考えるより、身体の力に強く依拠するようになった。作品が余程小さくない限り、机ではなく床を使うことにしている。

これは新しいアトリエに引っ越したときのブログ。

『年末から年始にかけて引っ越しに追われていました。7年間通い続けた馴染みの場所を離れ、広くて新しいアトリエに移りました。移転に当たって考えたのは床を最大限に使うこと。そのため、前のアトリエで使っていた作業台を思いきって無くすことにしました。新しいアトリエはがらんとして床ばかりが目立ちます。すべての作品を直に床に敷いて書くことにしたのです。確かに机上の方が楽ですが、それでは手先の技巧が勝ち過ぎてしまいます。これからは何を書くのも床の上。体の動きを出来るだけ画面に伝えたい。身体性にこだわるため、作品の大小にかかわらず床書きを自分に課すことにしました。』

もともと書の動きには東洋の舞踊や体術と共通するものがある。詩人の大岡信は、「書と言うものは舞踏に近いものといえるのではなかろうか」と指摘している。東洋の舞いの多くは、腰を低く落としたまま身体を水平に移動させる。手足の動きはゆっくりした円運動が基本となる。一方西洋では、例えばバレエのように垂直方向に高くジャンプしたり、手足を放射状に勢いよく突き上げたりする直線運動が多い。西洋の動きが一定のリズムで躍動するとすれば、東洋のそれは水の流れのように途切れることなく脈々と続いていく。

私は20歳の時に太極拳と出会った。太極拳はまさにこの東洋独自の動きそのもの。深く腰を落とし、一貫して気脈を保ちながら円運動を行う。

「魂が月のように輝く時、気は水のように流れる」

これは太極拳実践者の理想の状態を表す言葉である。書の表現(筆脈)と身体表現(気脈)には共通する「脈」がある。太極拳の動きを作品の制作に取り入れた場合、筆脈は途切れることなく綿々と続くので、からだの動きを軌跡のように紙面に残すことが出来る。すると、身体全体を使うことで偶然性や無意識性が働き、そこに本人の思惑を超えた何かが起きる。好きで始めた太極拳が奇しくも書に繋がった。

目の前の線やかたちが、確かに自分で書いたものでありながら、まるで自分が書いたという実感がない不思議に包まれることがある。気がついたら思いのほかいいものが出来ていたという瞬間を経験することがある。あらかじめ考えた青写真があると、どんなに出来が良くても結果は100点止まり。だが、こうした他力が介在すると予期せぬ150点の佳作が生まれる。

私はBSの「現代日本学原論」という番組に出演した際、筑紫哲也さんを通じて陶工・河井寛次郎の『手考足思』という言葉を知った。河井寛次郎は、頭でっかちでなく手足を使うことで外部の力を呼び込み、『未だ見ぬ私が見たい』と言った。以後、私はいつもこの言葉を大切にしている。書の本質は身体性の中にあると考えているからである。

ところで海外でワークショップをする時、「腰を落として」とか「腰を使って」とか、説明の中で「腰」という言葉を実に頻繁に使う。だが日本語の「腰」にぴたりと当てはまる外国語が見当たらない。一般的には英語なら "back" 、イタリア語なら "schiena"となる。でもこれは腰を含めた背中全体を指す言葉。西欧には「腰」を特定する語が乏しく、日本語ほど「腰」という部位に重きが置かれていないことが分かった。

書と時間性

あなたは線の流れを追うことで、私の筆の動きをたどることが出来ます。時間とともに筆がどんなふうに動いていたか、まるで制作現場にいたかのように想い描くことが出来ます。絵画は色やかたち、空間を表現します。私は画面の中に時間を表現したいのです。私がその時そこに生きていた証しとして。

書の場合、一旦筆を紙に置いたらもう後戻りは出来ない。一度書いた線を取り消すことは出来ない。後はただ前へ前へと書き進むだけである。文字を書いている以上、一画目から始めて最終画を書き終えたらそれで終わりである。スタートからフィニッシュまで、作品は一定の時間の中で時の流れに沿って現前していく。書について、音楽や舞踊との類似性を指摘される所以である。 書の優れた作品を前にすると、書きはじめから書き終わりまで、無意識に筆線を目で追いかけていることがよくある。その時、ここは勢いよく一気呵成に、ここは慎重にじっくりとなど、筆がどんなふうに動いていったか、まるで製作現場にいたかのように書き手の筆の動きを想い描くことが出来る。

この観点に立つと、筆の轍(わだち)とは製作現場の時の痕跡であるとも言える。少し大げさに言えば、書を書くということは、見ることの出来ないその場限りの時の流れをかたちあるものに定着させる営みであると言えるのではないか。

私は海外でいろいろな抽象ドローイングを直に見てきた。なかには書に似たようなものもたくさんあった。だがその多くは、書のように書きはじめから書き終わりまで描線をうまくたどることが出来なかった。また、描線そのものに表情を与えようとする作品も少なかった。線質そのものより線によるコンポジション、つまり線と線との関係性を踏まえた画面構成の方に重きが置かれていた。だから何度も重ね書きされていてストロークの速度や深度が読み取りにくい。総じて、作品の中に時間の流れを読み取ろうとしても難しかった。

私は欧米の抽象絵画との比較の中で、やはり書には時間美というものが存在するのではないかと感じた。

禅に、" 今、ここ "という教えがある。過去は過ぎ去ったものであり決して戻らず、また未来は未だやって来ない。どうにもならない過去を悔い、やって来ない未来を憂いても始まらない。私たちには「目前にある今」しかない。わき目もふらず" 今、ここ "を生きぬくことの大切さを禅は教えている。私はこの言葉を知って以来、パフォーマンスの時、かけがえのない現在という一瞬を強く意識するようになった。縁あって集まっていただいた方たちに見守られながら、その日その時一回限りのパフォーマンスを行う。パフォーマンスの間、私は一期一会の方々と"今"を共有する感覚を強く感じるようになった。そして"今"を共有した証の如くパフォーマンスの跡を残せたらいいと思う。

書と自然性

筆を置くと、墨は私の手を離れ紙の上をゆっくりと滲みはじめます。やがて乾いてぼかしを残します。これは不測の現象です。でも、だからといって抑え込むようなことはしません。技術は自然を制御します。私は自然の作用と寄り添いながら、あえて偶然の美を受け入れていきたいと思っています。

パフォーマンスの直後、「出来上がった作品はどうするのですか?」とよく訊かれる。「乾いた後で引き取ります」と答えると「撤収までどれくらいかかりますか」とまた訊かれる。 だが実を言えば、拍手の後もまだパフォーマンスは続いている。紙に放たれた墨は、観客が去った後も生きもののように動いている。墨が完全に乾ききるまで、墨跡は刻々と変化しながらパフォーマンスを続ける。観客の方々は私が関与した前半部分を見たに過ぎない。 筆を置くと、墨は紙の上をゆっくりと滲みはじめる。乾ききると溜まりが紋を残す。私はこうした人の手の届かない作用を作品の中に取り込みたいと思っている。

墨のにじみや溜まりは自然が生み出す現象のひとつであって、書き手には制御しきれないもの。だが、制御出来ないからと言って排除するのでなく、逆に積極的に受け止めて、自然の力とともに作品を完成させていきたい。

これは、まだミラノにアトリエを設けて間もない頃のブログ。当時はキャンバスにアクリル絵具で作品を制作していた。

『キャンバスはアクリル絵具との相性が抜群です。でもアクリル絵具には墨のような「あそび」や「雑味」はありません。工業製品として常に均一で安定している反面、偶然性の入り込む余地のない素材です。なかなかこれに馴染めずに戸惑っていました。

先日、墨と相性が良さそうなキャンバスを見つけた。布地がきめ細かくて肌触りがいい。これをいつか試そうと機会を待っていた。

この一週間まるで梅雨のような天気が続いていて、昨日も雨の一日。アトリエの窓を全開放して部屋の中に湿気をいっぱいに取り込む。淡墨をそっとキャンバスの上に落としてみる。すると、たちまち墨がキャンバスの上を泳ぎだした。久しぶりにホームグラウンドに帰ってきた生き物のように。刻々とにじみとたまりが変化していく。窓は一晩中開けたままにしておく。翌朝、着替えももどかしくベッドから起きだす。作品はすっかり乾いていて、夜中に墨と水とがたわむれた跡が残っていた。』

墨と水が出会うと魔物に変わる。にじみやたまりは変幻自在で決して思い通りにはいかない。だからこそ飽きない。我を出し過ぎてはいけない。自分の仕事は半分まで、後の半分は素材がもつ自然の力にゆだねる。筆を置いた瞬間が完成の時ではない。素材に宿る自然の力を借りて作品を仕上げる。一方、西洋絵画は向かう方向が全く違う。特に油絵の場合、その日の気温や湿度で絵具の発色や伸びが変わってしまったら画材として不可ということになってしまう。彼らにとって技術とは自然を制御するものであるという考えが強い。 西洋の "Nature"という言葉は、"Man"に対する相対的な概念として存在する。そこでは、主体である「人」と客体である「自然」が対峙している。「自然」は「人」によって制御される対象になる。一方東洋の "自然"という言葉は、もともと人を含めた万物全体を示している。人は自然の一部。自然を敬い、自然を畏れながら、自然とともに生きていく。 私は自然の作用と寄り添いながら、あえて偶然の美を受け入れていきたいと思っている。

What are the attributes of calligraphy?

Calligraphy is said to have both "form" and "meaning". In this case, the "form" refers to the positioning and shapes in the work - essentially, the features of the lines. Tsutomu Ijima (井島勉), a scholar of Western aesthetics, has stated, "Calligraphy is the art of characters; it is a genre of visual arts." Also, calligrapher Kanzan Samejima (鮫島看山) has said, " Calligraphy comprises the beauty of lines - it is the fine art of borrowing the material of characters, and expressing their beauty in lines." We can see that calligraphy is thought of as a visual art utilizing characters.

Then what about "meaning"? So long as calligraphy inculcates characters, words, etc., people will inquire as to what is written, and the meaning thereof. Shotaro Koyama (小山正太郎), an artist of Western painting, once said, "Calligraphy is literature." His idea was that because calligraphy includes characters, it is a kind of literature, rather than an art form. Moreover, calligraphy can attach a great deal of meaning to the characters and words which cannot be fully expressed in printed letters alone. This is because it is possible to interpret not only the personality of the calligrapher, but also his/her thoughts, emotions, and more by viewing how the calligrapher has written those characters and words.

In addition to the above-mentioned "form" and "meaning", I have come to consider the attributes of calligraphy to include 'body', "time", and "nature". This is a viewpoint that calligraphy delineates the tracks of the body's motions, and is at one with nature. I came to feel this strongly through my work abroad.

Calligraphy and 'body'

A piece of paper is laid out on the floor. I do not face the paper, but rather I 'enter into' it. First, I spread my feet on the paper, lower my body a bit, and then draw arcs with my hands and feet. This is similar to the movements of the Chinese exercise method tai chi chuan (太極拳) . Rather than me writing characters using my head and hands, the characters are left on the paper as tracks of my body as it writes.

Although these days we can enjoy comfortable daily lives thanks to high tech, on the other hand, we have also lost opportunities to use our bodies freely. For instance, concerning characters themselves, formerly we wrote them skillfully with brush and ink. This method was later replaced with writing utensils, but from antiquity to today, humans have always carried out the act of writing by hand. However, with the explosive spread of computers, cell phones, and other devices, characters are changing from something we "write" to something we "type". This historic change we are experiencing is a dramatic one with no precedent in the long history of character transcription.

Writing characters by brush and ink is now rare; in such an environment, calligraphy has taken on a significance it did not have before. That is the recovery of 'body' due to calligraphy - in other words, through calligraphy, one can experience using one's body consciously, or recognize again the power residing in one's body.

While teaching calligraphy in Japan and Italy, I came to wonder if calligraphy is not a kind of physical exercise. In calligraphy, a model example to be imitated is placed to the student's side, and then to the degree possible, the student attempts to write so that the features of the example piece are portrayed. When finished, the student's work is compared to the model, checking for aspects needing improvement, and the process is then repeated. If the method of moving the brush is mistaken - in other words, the body is used incorrectly - the result shows up on the paper. It is not necessary to take a video to see this; when the written lines and shapes are seen with an experienced eye, the problems in the usage of the body are clear.

In calligraphy, once one starts writing, there is no going back, and there is no way to re-do something. One must focus one's attention until the end, while continuing to correctly control the movements of the body.

Once I realized that calligraphy is a kind of physical exercise, I modified my teaching method so as to ascertain how students were utilizing their bodies. In the classroom, I would not check the students' brush movements, but instead would check how they moved their bodies while writing. When the form was correct, a correct result followed. The exact same method worked well for both Japanese and Italians.

On the other hand, what about the works being created? Rather than me thinking with my head, I came to depend greatly on the strength of my body. So long as the piece is not extremely small, I do the writing on the floor, rather than on a desk.

Here is my blog entry from when I moved to a new atelier (studio):

"I was busy moving from the end of last year until the beginning of this one. Leaving behind the location I had grown used to over seven years of commuting, I moved to a spacious, new studio. With the move, I thought to maximize the usage of the new floor. For that, I boldly got rid of the workbench I'd been using at the former studio. The floor at the new facility is the only thing which stands out, and I now lay all my drawing paper directly on the floor to do my work there. Working at the workbench is certainly easier, but in that case, the skill of my hand overwhelms everything else. From now on, whatever I write will be done on the floor. As much as possible, I want to transmit my body's movements to the paper. Because I'm focusing on my body, regardless if the piece is large or small, I make myself write it on the floor."

――

From the beginning, calligraphy's movements have had elements in common with the dances and physical arts of the East. The poet Makoto Ooka (大岡信) conjectured, "Can we not say that the thing called "calligraphy" is close to being a dance?"

In many of the dances of the East, the dancer drops down low, and then, while in that same position, moves their body horizontally. The movements of the hands and feet are basically comprised of slow circles. In contrast, in the West - in ballet, for instance - the dancers jump high in a vertical direction, energetically spread their hands and feet outward, etc. These kinds of straight-line motions are common in the West. If Western movements accompany a specific rhythm, Eastern movements are like the flow of water, moving on continuously without interruption. I first got to know tai chi chuan when I was 20 years old. Tai chi chuan is precisely that style of movement unique to the East. A dancer drops down low and carries out circular movements continuously, while maintaining their spiritual energy.

"When your soul shines like the moon, your spirit will flow like water."

This saying exemplifies the ideal state of a tai chi chuan practitioner. There is a common thread in calligraphy and tai chi chuan - when the movements of tai chi chuan are introduced into the production of a work, the brush movements continue without pause, so it is possible to leave tracks of body movements on the paper surface. Then, by using the whole body, chance and unconsciousness come into effect, and something beyond one's own expectation happens there. The tai chi chuan which I started for enjoyment became strangely connected to calligraphy.

Though the lines and shapes in front of me were certainly written by me, there are mysterious times when there is no actual feeling of my having written them at all. Also, there are moments when I happen to notice that something good was created unexpectedly. If there is a blueprint drawn up beforehand, no matter how well the work is done, the end result based on the blueprint can only reach 100%. But when this form of power from outside is involved, an unexpectedly fine piece which attains 150% may be born.

Once when I appeared on the satellite broadcast TV program The Principles of Modern Japanology (現代日本学原論), from the famous journalist Chikushi Tetsuya (筑紫哲也), I learned of the expression "Shu-kou-Soku-shi" ("The hands consider, and the feet think.") of the potter Kanjiro Kawai (河井寛次郎). Mr. Kawai did not over-think things, but rather called upon power from outside himself by using his hands and feet. He once stated, "I would like to see the me I have yet to see." Since then, I have always valued these expressions, because I consider the true essence of calligraphy to be in this physical aspect.

By the way, when I do a workshop overseas, the word "koshi" (腰, "lower back") is used quite frequently in explanations - for instance, in expressions such as, "the lower back is dropped" and "using one's lower back". But a term which precisely expresses the Japanese word "koshi" is not easy to come up with in foreign languages. In English, it generally is translated as the word "back"; in Italian, it becomes "schiena". But these words indicate the whole back, including the lower back. A word to specify "lower back" was scarce in Europe, and I learned that this part of the body is not considered as important there as it is in Japan.

Calligraphy and time

By following the flow of a line I have drawn, it is possible for you to visualize the movements of my brush. One can conceptualize how the brush moved through time, as if the viewer was at the production site. A painting expresses colors, shapes and space; on the canvas, I'd like to express time - as evidence of my having lived there then.

In calligraphy, once you set your brush to the paper, there is no going back. It is impossible to erase a line which is written. At that point, the calligrapher must simply continue on with the writing. So long as a person is writing characters, they begin with the first stroke and finish up with the last one. From start to finish, in a fixed period of time, the piece is gradually realized together with the flow of time. This is a reason people point out the similarities between calligraphy and music, dance and other forms of artistic expression.

When looking at an exceptional piece of calligraphy, I often find myself unconsciously following the brush strokes with my eyes, from the starting point of the writing to its finish. Then I can imagine how the calligrapher's brush moved - in one location energetically with a burst of enthusiasm, then in a different location slowly and carefully - as if I had also been at the production site.

When one has this viewpoint, it can also be said that the tracks of the brush are the traces of the time flow at the production site. Stating it in a slightly exaggerated way, can we not say that writing calligraphy is the work of setting on canvas in a visible form the otherwise invisible flow of time at that unique production location?

While overseas, I have seen various abstract drawings directly. There were numerous ones which resembled calligraphy. However, with many of those, I could not follow the drawn lines well from the start of the drawing to the finish. Also, there were few works which attempted to give expression to the lines themselves. More than the quality of the lines themselves, priority was given to the composition of the lines - in other words, the composition of the canvas as it concerned the relationship between the lines drawn. So it was difficult to read the speed or depth of strokes which had been written over several times. It was difficult even if I merely attempted to 'read' the overall flow of time in the work.

Through my comparisons of calligraphy with European and American abstract paintings, I came to feel that in the end, calligraphy contains a sense of the beauty of time.

There is a teaching in Zen Buddhism which translates as, "Be here now". The past has passed and will never return, whereas the future has not come yet. If a person regrets the unchangeable past, or feels gloomy about their future which has not yet come, nothing will start. All we really have is "the present in front of us". Zen teaches us the importance of being completely absorbed in living "here and now".

Since I learned about this teaching, at performances, I have become very conscious of the present moment, the irreplaceable present. A one-time-only performance takes place that day, at that time, as I am being observed by the people who destiny has kindly gathered together with me. During each once-in-a-lifetime performance, I have come to feel a strong sense of sharing the "now" with members of the audience. I think one should be able to leave behind traces of such performances, like proofs that the "now" was shared.

Calligraphy and nature

When I lay down my brush at the end of a performance, the ink takes on a life of its own, and slowly begins to spread on the paper. Finally, it dries, and leaves gradations of a blur. This is an unexpected phenomenon. But even so, I do not try to constrict it. Technology controls nature. Instead, I wish to intentionally accept the beauty of the unplanned, while working hand in hand with nature.

After a performance, I am often asked, "What do you do with your finished works?" I answer, "After they've dried, I bring them back with me." Hearing this, many questioners follow up with, "So how much time does it take until you can leave?"

But to tell the truth, a performance still continues after the applause is over. After an audience has left, the ink set onto the paper is still moving - like a living thing. Until the ink is completely dried, the lines continue their 'performance' as they change, moment by moment. The audience has only seen the first half - the part in which I participated.

When I lay down the brush, the ink slowly begins to spread on the paper. When the pooled ink finishes drying, it leaves a specific pattern. I want to incorporate such effects which are not due to human hands into my works.

The spreading or pooling of ink are phenomena of nature, which a writer cannot totally control. But even if they cannot be controlled, this is no reason to exclude them; rather, I try to positively accept this, and complete my works together with the power of nature.

Below is a blog entry from when I had just established a studio in Milan. I was then producing a work with acrylic paint on canvas.

"The canvas has outstanding chemistry with the acrylic paint. But there's no "play" or "miscellaneous flavor" in acrylic paint, like there is in Chinese ink. As industrial products, acrylics are always uniform and stable; on the other hand, as material, they have no room for chance to enter. So I was really struggling about how to get used to this.

Then the other day, I found a canvas which seems compatible with Chinese ink. The fabric is fine, and agreeable to the touch. I was waiting for a chance to try using this sometime.

This past week, the weather has been like the rainy season; it also rained all day yesterday. I opened wide a window of the studio, and took in lots of humidity. I dropped pale Chinese ink on the canvas quietly. Then immediately the ink began to 'swim' on the canvas - like a creature which has returned to its home after a long time. The spreading and pooling of ink changes every moment. To see what would happen with the ink, I left the window open all night.

The next morning, putting on my clothes was a bit frustrating after I got out of bed, because I wanted to quickly see the result of my work from the previous night. The work had completely dried, and the traces where the ink and water had 'frolicked together' during the night were left behind."

When they come into contact, ink and water metamorphose into something mysterious. The ink pools and spreads as it wishes, acting like a strange illusion, never behaving as one expects. This is precisely why I never get tired of it. I should not put my own self into a work to an excessive degree. My work is half, while the other half involves relying on the natural power of the material. The moment I lay down my brush is not the time of completion. I complete a work through 'borrowing' the natural power residing in that material.

On the other hand, Western painting has a totally different viewpoint. Particularly in the case of oil painting, depending on that day's temperature and humidity, if factors such as the coloring or elasticity of the paint change, the paint may become inappropriate for use. Many Westerners hold strongly to the view that technology is a means of controlling nature. In terms of language, the word "Nature" in the West exists as a concept which is relative to "Man". Therein, the subject "Man" confronts the object "Nature". Nature is deemed to be an object to be controlled by humans. In contrast, in the Orient, the word "Nature" indicates the whole of creation, including human beings. Humans are part of nature - living our lives while respecting and fearing it. Anyway, as I said earlier, I wish to intentionally accept the beauty of the unplanned while working hand in hand with nature.

Translation: Ray Hrycko

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?