CSA農家の矛盾とジレンマ:日米のCSA比較【卒論まとめ③】

まとめ①では導入部を、まとめ②では調査方法と考察の一部をお届けしました。最終回は総括と参考文献を記載しています。調査結果の詳細や参考文献の入手方法については個別にお尋ねください。

4. 総括

4-1. CSA原則と運営実態の乖離

日本・ケンタッキー州のどちらにおいても、CSA農家はオペレーションの各段階において会員側に譲歩をすることで自らの負担を増やし、自己搾取の構造を生み出す傾向にあった。

この傾向は特に日本のCSAの受け渡し方法、梱包作業、支払いといった場面に顕著に現れていた。

【例1:受け渡し】

日本ではピックアップポイントを設けることが難しく、梱包・発送・配達の手間がかかる

<要因>

・物理的アクセスが悪い(会員が車を使わない)

・周囲の理解不足(場所確保が困難)

【例2:梱包】

日本のCSAでは梱包作業にかける時間が多い

<要因>

・配送を行う

・消費者からの清潔さ・個包装の要求

【例3:支払い】

日本のCSAは支払い方法に関しての柔軟性が高いため、支払い確認や依頼の作業負担が高い

<要因>

・CSA理解の低さ(長期前払いに理解が得られにくい)

・現金利用率の高さ(オンライン決済を適用しにくい)

日本のCSAの小さく、タイトなコミュニティにおける会員との距離の近さが経済活動の社会ネットワークへの「埋め込み」構造をつよめ(Galt, 2013, p. 341)結果として農家側の義務感につながったと考えられる。

4-2. 販路の一つとしてのCSAか、存在意義としてのCSAか

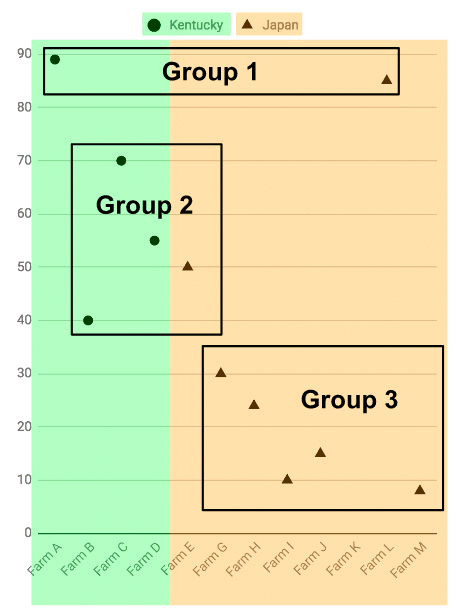

各農場の売上全体に占めるCSA販売額の割合は、以下の通り。(縦軸が割合:%)ここではその割合によってCSAをグループ1〜3に区分した。

CSA事業の捉え方は以下のA、Bに大別された。

A)農場のミッションを達成する核、自らの存在意義としてのCSA

【グループ1】CSAへの依存度が80~90%

・農家の収益性を追求しない

・会員による参画の重視

・活動の継続によるコミュニティへの奉仕を目的化

…提携の流れを組む日本の源流CSA、非営利目的のケンタッキー州のCSAが該当。

B)収入を安定させるための販路の一つとしてのCSA

=「事業家的アプローチ」(Ostrom, 2007, p. 20)

【グループ2】CSAへの依存度が40~70%

・CSAが経営の安定に貢献

・CSAの規模拡大を目指す

…ケンタッキー州のほとんどのCSAが該当。

【グループ3】CSAへの依存度が30%以下

・CSA以外に安定した販路を持つ

・CSAの規模拡大をあまり志向しない

…日本の多くのCSAが該当。

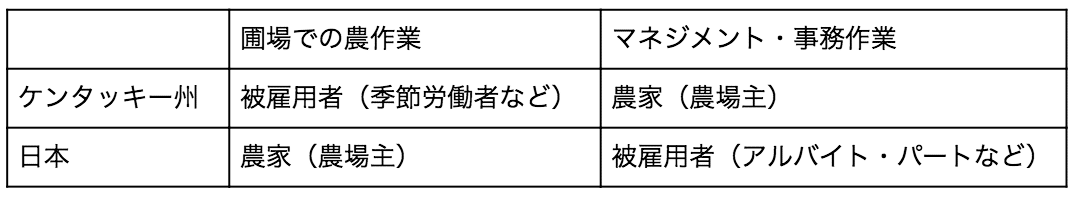

4-3. CSA農家の自己認識の相違とスタッフの作業分担

日本とケンタッキー州では農場主と被雇用者の作業分担の違いが顕著に見られたが、これは農家の自己認識の相違に依存していた。

支配的だった自己認識(アイデンティティ)はそれぞれ

日本:生産者(百姓)

ケンタッキー州:経営者(オーナー)

であり、それに伴う役割分担は以下のパターンがほとんどであった。

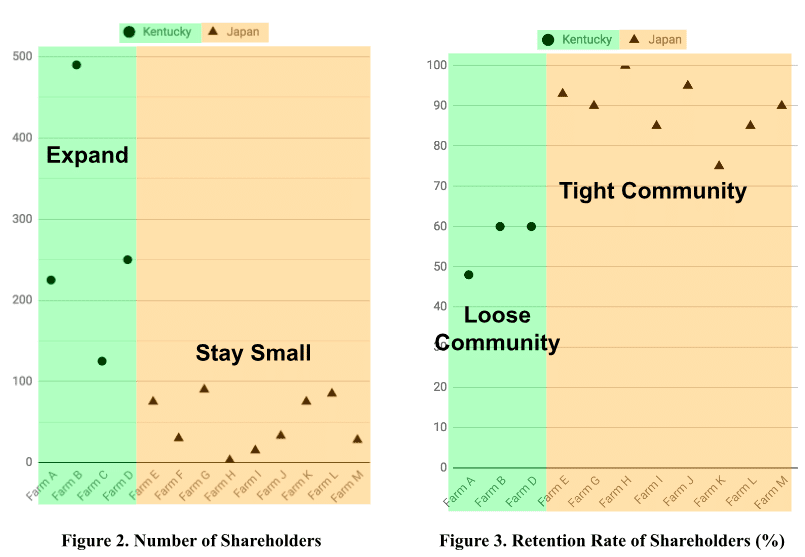

4-4. コミュニティ規模とCSA戦略

(左図)ケンタッキー州と日本の各CSA会員数

日本(右側オレンジ部分):平均48人

ケンタッキー州(左側緑色部分):平均272人

(右図)会員の継続率

日本(右側オレンジ部分):平均89%

ケンタッキー州(左側緑色部分):平均56%

ケンタッキー州に多く見られたCSA戦略

・会員数が日本よりも圧倒的に多い

・新規会員獲得を常に目指す

・利便性の向上によって会員の満足度を高めようとする

・会員の継続率は低く、会員の出入りが激しい

=> 拡大路線

=> (副作用)コミュニティ感覚の希薄化

日本のCSAに多く見られたCSA戦略

・会員数はケンタッキー州よりも圧倒的に少ない

・拡大をあまり志向せず、「顔の見える関係性」を重視

・会員の継続率は著しく高い

=> 小さくとも密なコミュニティを維持

=> (副作用)発展しにくい

4-5. 日本におけるCSA議論の発展のために

本研究の限界

・ケンタッキー州のCSAサンプルの少なさ

・CSA農家の認識や戦略における定量データの欠如

今後の議論に期待されること

・CSAの運営方法における多様性を認識すること

・原則に固執してその可能性を狭めるのではなく、時代変化に合わせて多様なステークホルダーやリソースを包含し発展していく柔軟性を持たせること

・理想論を語るばかりではなく、CSA農家が抱える矛盾やジレンマを見過ごさないこと

・課題について対処していくため具体的な運営実態についての情報を集約・共有していくこと

参考文献

Brown, C. and Miller, S. (2008), “The impacts of local markets: a review of research on farmers market and community supported agriculture (CSA),” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 90(5): 1296-1302.

Cone, C. and Myhre, A. (2000), “Community-supported agriculture: A sustainable alternative to industrial agriculture?,” Human Organization, 59(2): 187-197.

Farmer, J., Chancellor, C., Robinson, J., West, S., and Weddell, M. (2014), “Agrileisure – farmers’ markets, CSAs, and the privilege in Eating Local,” Journal of Leisure Research, 46(3): 313-328.

Galt, R. (2011), “Counting and Mapping Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) in the United States and California: Contributions from Critical Cartography/GIS,” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 10 (2): 131-62.

Galt, R. (2013), “The Moral Economy Is a Double-edged Sword: Explaining Farmers' Earnings and Self-exploitation in Community-Supported Agriculture,” Economic Geography, 89(4): 341-365.

Galt, R., Bradley, K., Christensen, L., Kim, J., and Lobo, R. (2016), “Eroding the Community in Community Supported Agriculture (CSA): Competition's Effects in Alternative Food Networks in California,” Sociologia Ruralis, 56(4): 491-512.

Groh, T. and McFadden, S. (2000), Farms of tomorrow revisited community supported farms, farm supported communities. Kimberton, PA: Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Association.

Hatano, T. (2008a), “CSA ni yoru seisansha to shohisha no renkei (The partnership between producers and consumers via CSA),” Agriculture and horticulture, 83(1): 190-196.

Hatano, T. (2008b), “The Organic Agriculture Movement (Teikei) and Factors Leading to its Decline in Japan,” Journal of rural and food economics, 54(2): 21-34.

Hatano, T. (2013), “Status of CSA and Factors of stagnation of TEIKEI: Swiss CSA (contract farming between producers and consumers in proximity) and TEIKEI Principles,” Journal of the Japanese Society of Organic Agriculture Science, 5(1): 21-31.

Henderson, E. and En, R. (2007), Sharing the Harvest: A Citizen’s Guide to Community Supported Agriculture, White River Junction: Chelsea Green Publishing Company.

Janssen, B. (2010), “Local Food, Local Engagement: Community-Supported Agriculture in Eastern Iowa,” Culture & Agriculture, 32(1): 4-16.

Karasaki, T., Fukuyo, N., Sakane, I., and Ishida, K. (2012), “The Regional Effects of CSA and the Possibility of Establishment,” Journal of the Rural Life Society of Japan, 56(1): 25-37.

Lamb, G. (1994), “CSA: Can it become a basis for a new associative economy?,” Threefold Review, 11: 39-44.

Lass, D., Bevis, A., Stevenson, G., Hendrickson, J., and Ruhf, K. (2003), Community Supported Agriculture Entering the 21st Century: Results from the 2001 National Survey, Amherst, MA: Dept. of Resource Economics, University of Massachusetts.

LeRoux, M., Schmit, T., Roth, M., and Streeter, D. (2010), “Evaluating marketing channel options for small-scale fruit and vegetable producers,” Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 25(1): 16-23.

Murase, H., Maeno, T., and Hayashi, M. (2010), “A Study of CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) Regarding Regional Development : A Case Study of Menno Village Naganuma's Activity,” Journal of the Japan Association of Regional Development and Vitalization, 1: 41-51.

National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO) (2016), CSA (Chiiki shien gata nōgyō) dōnyū no tebiki (Guidance for introducing CSA), http://www.naro.affrc.go.jp/publicity_report/publication/files/csa-guide.pdf, accessed 21 January 2019.

New Roots, Inc. (No Date), Fresh Stop Markets, https://newroots.org/fresh-stop-markets/, accessed 21 January 2019.

Ostrom, M. (2007), “Community supported agriculture as an agent of change,” in C. Hinrichs and T. Lyson (eds.), Remaking the North American Food System, University of Nebraska Press, 99-120.

Ostrom, M. (1997), Toward a community supported agriculture: a case study of resistance and change in the modern food system (Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison).

Pole, A. and Gray, M. (2013), “Farming alone? What's up with the "C" in community supported agriculture,” Agriculture and Human Values, 30(1): 85-100.

Rakuten, Inc. (2017), Rakuten to Tele-farm, chiiki shien gata nōgyō (CSA) sābisu “Raguri” wo kaishi (Rakuten, Inc. and Tele-fa-m started a CSA service named Ragri), https://corp.rakuten.co.jp/news/press/2017/0405_01.html, accessed 21 January 2019.

Schnell, S. (2007), “Food with a farmer’s face: Community-Supported Agriculture in the United States,” Geographical Review, 97(4): 550-564.

Schnell, S. (2013), “Food miles, local eating, and community supported agriculture: putting local food in its place,” Agriculture and Human Values, 30(4): 615-628.

Small Farm Central (No Date), CSA Solution Hub, http://www.memberassembler.com/hub/comprehensive-csa-models, accessed 21 January 2019.

Tegtmeier, E. and Duffy, M. (2005), “Community supported agriculture (CSA) in the Midwest United States: A regional characterization,” Leopold Center Pubs and Papers, 151.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Agricultural Library (2018), Community Supported Agriculture, https://www.nal.usda.gov/afsic/community-supported-agriculture#what, accessed 21 January 2019.

Uribe, A., Winham, D., and Wharton, C. (2012), “Community supported agriculture membership in Arizona. An exploratory study of food and sustainability behaviours,” Appetite, 59(2): 431-436.

Wharton, C. and Harmon, A. (2009), “University Engagement Through Local Food Enterprise: Community-Supported Agriculture on Campus,” Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 4(2): 112-128.

=================================

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?