慧子/10.リベット実験 Keiko/10. The Ribet Experiment

前回はこちら/Previous episode

慧子はノートパソコンのディスプレイを見続けて疲れた目を休めるため窓際に行き、そとを眺めた。12月だというのに、窓の外の木々は色こそあせているものの、緑の葉を茂らせ、午後の柔らかな日差しがあたりを包んでいる。

Keiko went to the window and looked out to rest her tired eyes from staring at the laptop screen. Though iI was December. The leaves of the trees outside the window were green, and the soft afternoon sun was shining.

シリコン・バレーの冬は暖かい。気温が10度を下回ることはなく、東京のように冷たい木枯らしが吹くわけでもなく、夏場と変わらない衣服の上にすこし厚手のトレーナーを羽織るだけで、屋外でも十分に温かく過ごすことができた。寒さに弱い慧子にとっては、実にありがたい気候で、今では、ここに来てよかったと心から思っていた。

Winters in Silicon Valley are warm. The temperature did not drop below 10 degrees Celsius, nor did it blow cold wind like in Tokyo. Keiko was able to stay warm enough even outside just by putting on a slightly thick sweatshirt over the clothes that are the same as in summer. who was vulnerable to the cold, Keiko had come to feel from the bottom of her heart that she was happy to be here.

今、慧子は、母が勤めている神経工学研究所の図書館にいる。日本で人型ロボットの研究をしていた母は、この研究所にスカウトされて渡米し、それに慧子もついてきたのだった。

慧子は、ここの図書館の資料を使って、人間の意識と無意識の関係についてのエッセイを書いているところだ。

Keiko was now in the library of the Institute of Neuroscience, where her mother worked. Her mother, who had been researching humanoid robots in Japan, was scouted by this research institute and came to the United States, and Keiko accompanied her.

Keiko was writing an essay on the relationship between human consciousness and unconsciousness using the materials in this library.

科学の教師ティムが、クリスマス休暇前の課題として秋学期の授業で取り上げたテーマの中から好きなものを選んで科学エッセイを書くように指示し、慧子は、クラス討議のテーマだった無意識過程と意識過程の、一見逆転して見える関係をエッセイのテーマに選んだのだ。クラス討議以来、慧子は、このテーマへの関心を深め、関連する書籍を買い込んで読み込んだりしてきていた。

Science teacher Tim instructed her class to write a science essay on one of the themes that Tim had picked up in her fall semester classes as a pre-Christmas assignment. Keiko chosed the seemingly reversed relationship of the unconsciouss and conscious processes as the theme of her essay. Since her class discussion, Keiko has deepened her interest in the subject and had purchased and read related books.

母は、慧子が科学エッセイを書くと知ると、母が勤めるこの研究所の図書館を使うことを強く勧めてきた。外部に公開されている図書館ではないが、あるレベル以上の研究員の子弟に対しては、特別に入館許可が与えられるし、最新の資料が揃っているだけでなく、高速のインターネット回線があるので、ネット検索もスピーディに出来ると言うのだ。(著者注:小説の中では2005年です)

When Keiko's mother noticed that Keiko was writing a scientific essay, she strongly encouraged Keiko to use the library of the institute of her institute. mother works. She said to Keiko, "Although the library is not open to the public, children of researchers above a certain level are given special permission to enter the library. In addition, internet searches can be done speedily thanks to the high speed network of the institute.

しかし、慧子は、最初は母の誘いをことわった。母の勤め先に足を踏み入れることに抵抗があった。ハロウィンに始まって、サンクスギビング、クリスマスへとつづくイベント盛りだくさんな時期に入って、母が男性のクルマで送られてくる回数が増えたことを慧子は不快に感じていた。母の言葉の端から、その男性が研究所の同僚らしいとわかっていたから、なおさら、この研究所には近づきたくなかった。

However, Keiko initially turned down her mother's invitation. Keiko was reluctant to set foot in her mother's workplace. As Amecica entered the event-filled season starting from Halloween, Thanksgiving, and then Christmas, Keiko felt uncomfortable with the increasing the number of times her mother was sent off in a male car increased. That made Keiko feel uncomfortable. From what her mother said, Keiko thought the man was likely to be a colleague of hers, so Keiko didn't want to go anywhere near the institute.

だが、高校の図書館の貧弱さに呆れたことと、高速ネット回線に惹かれたことで、結局、慧子はこの図書館に足を踏み込み、一度来てしまうと病みつきになったのだった。幸い、母が慧子の前に顔を出すことはなかった。

However, being astonished by the poor quality of the high school library and being drawn to the high-speed internet line, Keiko ended up setting foot in this library, and once she got there, she became addicted to it. rice field. Fortunately, her mother never showed her face in front of Keiko.

ティムがクラス討議の題材にした無意識・意識・筋肉運動の時間関係は、元々は、脳科学者のベンジャミン・リベットが1983年に実験で明らかにしたものだった。ティムは実験の被検者は腕を上げたと言ったが、リベットの実験では、被験者は手首を曲げるという、よりシンプルで負荷の軽い動作を行っていた。そして、その実験で無意識の過程が意識的な過程に先立つという結果が示されのだ。つまり、被験者の脳内で手首を曲げる動作の準備ができ、その後に被験者は手首を曲げようと思い、そして被験者の手首が曲がった。

The time sequence among the unconscious, conscious, and muscle movements that Tim had made a subject of discussion in class was originally clarified by brain scientist Benjamin Libet in 1983. Tim said that the subjects in the experiment raised their arms, but in Libet's experiment, the subjects performed a simpler, less strenuous movement of flexing their wrists. And the experiment showed that unconscious processes precede conscious processes. That is, the subject's brain prepared for the motion of bending the wrist, then the subject intended to bend the wrist, and the subject's wrist flexed.

この実験結果に対する脳科学者たちの反応は「無意識の決定が意識的な決定に先行するなど、あり得ない」というものだった。リベットの実験結果を否定するための反証実験が次々と行われた。脳内神経の変化、被験者の意図、手首が曲がるタイミングのそれぞれを測定する方法に瑕疵があったのではないかという疑問もあり、リベットのものとは異なる動作と測定方法を用いた実験も行われた。ところが、こうした反証実験のほとんどがリベットの実験結果を追認する結果になってしまったのだ。

The reaction of neuroscientists to the results of this experiment was, "It is impossible that an unconscious decision precedes a conscious decision." A series of falsification experiments were conducted to deny the results of Libet's experiments. There were also questions about whether there were flaws in the measurement procedures used to measure changes in brain nerves, the subject's intentions, and the timing of wrist flexion. Therefore, falsification experiments that adopted different measurement procedures were also conducted. However, most of these refutation experiments ended up confirming Libet's results.

ここに至って、哲学者たちがリベットの実験結果をめぐる議論に加わってきた。人間の自由意志は哲学の最重要課題のひとつなので、その根拠を揺るがしかねない実験結果を哲学者たちは無視できなかったのである。実験からおよそ四半世紀が経とうとする2005年現在でも、リベットの実験結果は、脳科学および哲学の世界で熱い議論の対象となっている。

At this point, philosophers joined the debate over Libet's experimental results. Since human free will is one of the most important subjects of philosophy, philosophers could not ignore experimental results that had the potential to undermine the foundation of human free will. Even as of 2005, nearly a quarter of a century after the experiment, Libet's experimental results were still the subject of hot debate in the worlds of brain science and philosophy.

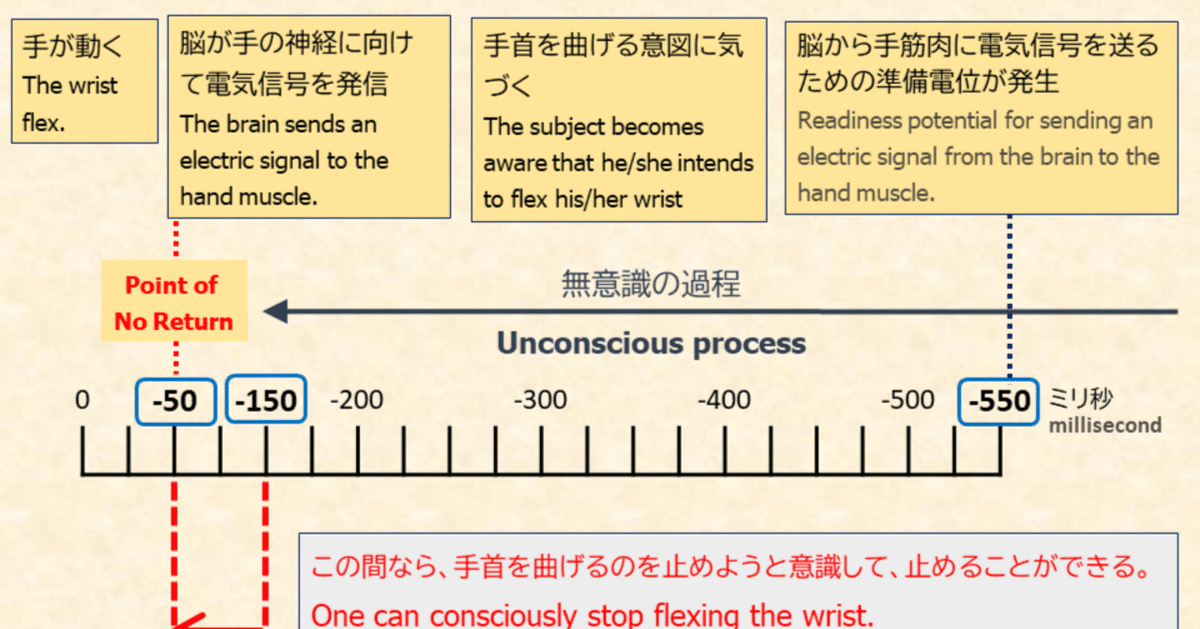

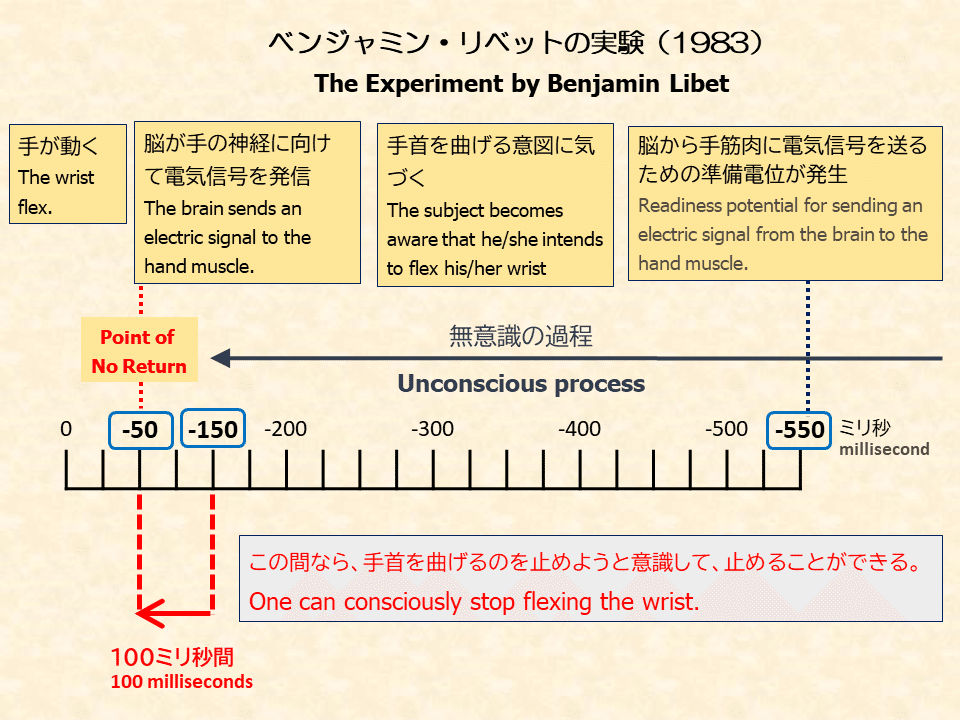

慧子は、エッセイを、自らの関心の起点となったリベットの実験から始めることにした。リベットの実験結果をエッセイの冒頭で簡潔に示せるよう、一枚の図式に整理した。この図式中で、実験に用いられた測定方法は省略されている。慧子は、測定方法はエッセイ本文でも触れず、注として文末に記載することにしていたのだ。リベットと異なる測定方法を用いた反証実験でも同じ結果が出ている以上、測定方法は決定的に重要な論点ではないと、慧子は考えていた。

Keiko decided to begin her essay with the Libet experiment, which was the starting point of her interest. She organized the results of Libet's experiments into a single diagram so that she could present them concisely at the beginning of her essay. In this scheme, the measurement procedures used in the experiments are omitted. Keiko did not mention the measurement method in the essay either. She planned to refer to the measurement procedures as a note at the end of the essay. Since the same results were shown in the rebuttal experiments using a different measurement procedures than those Livet applied, Keiko thought that the measurement procedures were not critical.

慧子は、手首が曲がったタイミングを0時点として時間をさかのぼっていく図式で実験結果を整理した。手首が曲がる500ミリ秒前、つまりマイナス500ミリ秒時点で、脳から手の筋肉に電気信号を送るための準備電位が発生する。ただ、この時点では、まだ電気信号そのものは発信されない。マイナス150ミリ時点で被験者は手首を曲げようと思う。この時点でも、まだ脳は電気信号を送っていない。マイナス50ミリ秒時点で手首を曲げるよう指示する電気信号が脳から手の筋肉に送られ、その50ミリ秒後、つまり0時点で手首が曲がる。

Keiko arranged the results of the experiment in a diagram that traces back time, with the point at which the wrist bends as point 0. 500 milliseconds before the wrist bends, i.e., minus 500 millisecond point, a readiness potential for sending electrical signals from the brain to the hand muscles is generated. However, at this point in time, the electrical signal itself has not yet been transmitted. At minus 150 mm, the subject wants to bend the wrist. In other words, the subject become aware of his/her intent to bend the wrist. Even at this point, the brain is not yet sending electrical signals. At minus 50 milliseconds, the brain sends an electrical signal to the hand muscles telling them to bend their wrists, and 50 milliseconds later, at time 0, they bend their wrists.

2005年現在、脳科学の世界では、無意識的な決定が意識的な決定に先行することについては、説得力ある仮説として公認されつつあるようだった。一方、哲学者の多くは、今でもリベットの実験結果に困惑しているという印象を慧子は受けた。そうした哲学者たちは、さまざまな反証実験でも否定されなかった科学的発見を完全に無視することもできず、かといって自由意志を否定することもできないというジレンマに直面しているように感じられた。

As of 2005, in the world of neuroscience, the idea that an unconscious decision preceeds the relevant conscious decision had come to be regarded as a convincing hypothesis. On the other hand, Keiko got the impression that the majority of philosophers were still puzzled by Libet's experimental results. They seemed to face the dilemma that while they could not completely ignore scientific discoveries that hade not been denied by various falsification experiments, they could not deny free will. .

興味深いのは、リベット本人は、自由意志の存在を否定しているわけではないことだった。被験者が手首を曲げようと思ってから脳が信号を発するまでに、100ミリ秒の間隔がある。この100ミリ秒の間に、手首を曲げる意図を意識的に撤回し手首を動かさずにいることができると、リベットは主張していた。つまり、意識は動作を起動することはできないが、抑制することはできると言うのである。リベットは、被験者が手首を曲げようと思った後に、100ミリ秒以内ならその意図を撤回できることを示す実験も行っていた。

Interestingly, Libet himself did not deny the existence of free will. There is an interval of 100 milliseconds between when the subject wants to bend their wrist and when the brain emits a signal. During these 100 milliseconds, Libet argued, one could consciously withdraw her/his intention to bend the wrist and keep the wrist still. Consciousness, he says, cannot initiate action, but it can suppress it. Libet conducted the experiments that showed that subjects could withdraw their intention within 100 milliseconds after intending to bend their wrists.

しかし、このリベットの主張に対して、慧子は疑問を持った。それは、手首を曲げる動作については、それを意識的に意図する500ミリ秒前に脳内で準備が始まるのに、手首を曲げるのを止めるために意識に許される時間が100ミリ秒しかないことから来ていた。その短い時間で、本当に意識して動作を止めることが出来るのだろうかと、慧子は疑問に思ったのだ。

However, Keiko had doubts about Libet's claim. That's because the brain prepares for a wrist flexion 500 milliseconds before consciously intending it, but the conscious mind has only 100 milliseconds to stop bending the wrist. Keiko wondered if one really could consciously stop the move to bend the wrist in such a minute time.

どうも、同じ疑問をリベットも抱いたようだった。彼は、この疑問に対する答えと考えられる主張をしていた。彼は、動作を起こすには無意識の準備が必要だが、動作を止める時にはその必要はなく、意識的な決定が即、動作につながると主張していた。

しかし、リベットは、その主張を実験で裏付けることはしていない。手首を曲げるのを止める意志決定に先立つ脳内活動はないことを証明する実験は、行われなかったのだ。

Libet seemed to have the same question as the one Keiko had. He made a claim that Keiko regarded as an answer to this question. He argued that while initiating an action requires unconscious preparation, stopping it does not, and that conscious decisions to stop the move were immediately executed .

But Libet did not back up his claims experimentally. No experiments were performed to prove that there was no brain activity prior to the decision to stop bending the wrist.

慧子には、「行動拒否としての自由意志というリベットの主張は苦し紛れの詭弁のように感じられた。リベットは自らが行った実験結果を前にして、後に他の脳科学者たちや哲学者たちが抱いたのと同じ不安、つまり、人間の自由意志が否定されてしまうとことへの不安を抱いたのだと思う。だから、自由意志が存在する余地を残したかった。

To Keiko, Libet's assertion of free will as a refusal to act seemed like a desperate argument. Faced with the results of his own experiments, Libet faced the same fear that later other neuroscientists and philosophers had: the denial of human free will. Keiko thought that Ribet wanted to leave room for free will.

慧子には詭弁と思われる、リベットのこの主張も、脳科学者たちの間ではおおむね受け容れられているようだった。一方、哲学者たちの多くは、この主張は受け容れがたいと感じながら決定的な反論もできずにいるように、慧子には見えた。

However, Libet's claim also seemed to be generally accepted among neuroscientists. On the other hand, it seemed to Keiko that many philosophers found this assertion unacceptable, but were unable to come up with a decisive counterargument.

ただ、一人だけ、非常に説得力のある反論を展開している哲学者がいた。それは、ダニエル・デネットだった。彼が2004年に発表した反論に慧子は大いに納得した。ただし、デネットの反論の一部は慧子がクラス討議の場で提起した「被験者はリベットの実験に参加すると決めた時点で自由意志を行使している」という主張と重なっていた。このため、慧子はエッセイでデネットの反論に触れるべきかどうかで迷っていた。

There was, however, one philosopher who presented a very persuasive counterargument. It was Daniel Dennett. A counterargument he published in 2004 was very persuasive to Keiko. However, part of Dennett's counterargument overlapped with Keiko's assertion that the subjects exercised their free will when they had decided to participate in Libet's experiment. This made Keiko wonder whether she should refer to Dennett's counterargument in her essay or not.

次回はこちら/Next episode

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?