#4 The Development of Japanese Calendars Part4

Although today's Japanese take the solar calendar for granted, it has only been about 150 years since its adoption. The traditions that have continued for thousands of years up to that point will not disappear any time soon and are still being passed down through generations. In this issue, I would like to introduce just a small part of these enduring traditions.

Calendar Customs that Remained from the Meiji Era

Until the Edo period, the lunisolar calendar contained many annotations and predictions, called 暦注 (Rekichuu: calendar notes), to indicate daily good or bad luck, events, weather, agricultural guidelines, etc. In other words, superstitions. Just as in modern times we believe in religions, ethnic cultures, and superstitions that at first glance seem unscientific. One of these calendar notes that remains in the calendars used by modern Japanese people is called 六曜 (Rokuyou).

In the Meiji era, as Japan leaned towards rationalism and scientism, the government believed that such unscientific superstitions should be excluded from calendars. However, calendars without these notes did not sell at all, and eventually, the government decided to retain them. One of these is 六曜 (Rokuyou), which remains to this day. It proves that ingrained cultures and customs cannot be changed overnight.

六曜 (Rokuyou) is said to be an ancient Chinese divination method, introduced to Japan around the 15th century. It was not widely and publicly used until the Meiji era.

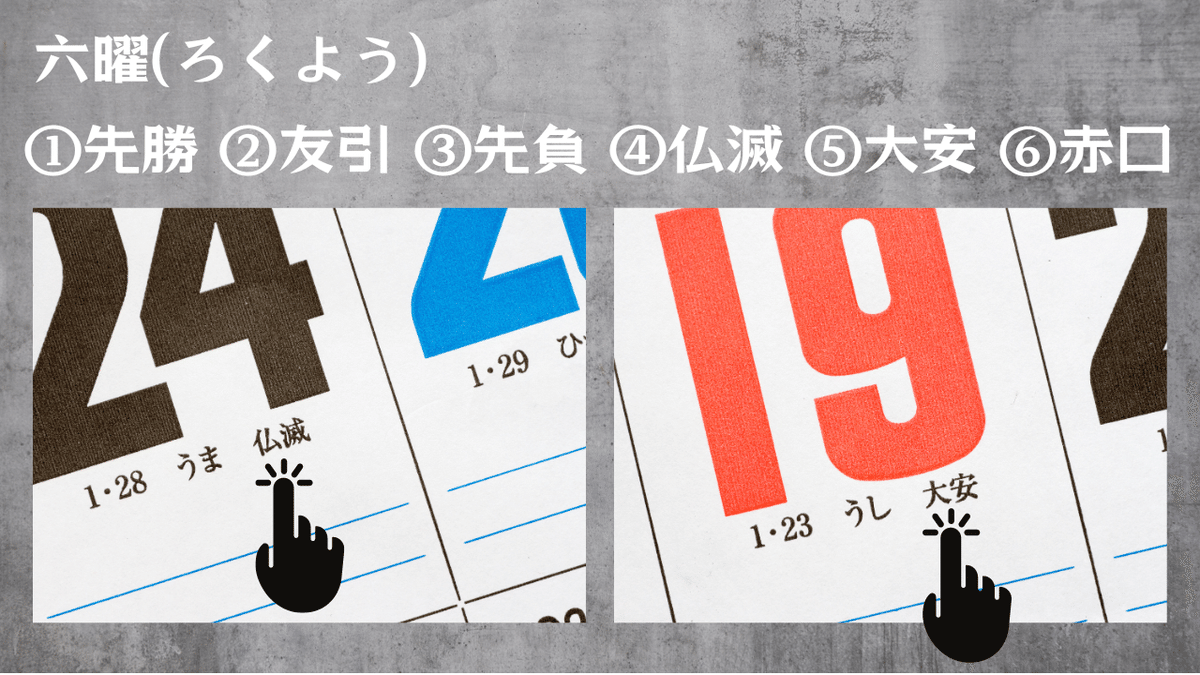

As the name suggests, 六曜 (Rokuyou) has six divination forecasts written within the date. See the image below. Each of these has several readings, but the most common ones are listed below:

(1) 先勝(Senshou) - Good luck for urgent matters. Good luck in the morning, bad luck in the afternoon.

(2) 友引(Tomobiki) - A day when you can't win the game. No funerals or other bad luck. Noon is a bad time.

(3) 先負(Senpu) - A day of modest calm. Bad luck in the morning, good luck in the afternoon.

(4) 仏滅(Butsumetsu) - All things are bad. Funerals and Buddhist memorial services are fine.

(5) 大安(Taian) - Good luck in all affairs. Particularly good for weddings.

(6) 赤口(Shakkou) - Particularly bad for celebrations. Noon is good luck.

Many Japanese people still refer to these notes to decide the date of a celebration or funeral, and so on. When you visit Japan, why not buy a calendar and pay attention to 六曜 (Rokuyou)?

Words Related to the Lunisolar Calendar That Remain in Modern Times

五月晴れ(Satsuki-Bare) And 五月雨(Samidare)

There are two Japanese phrases, "五月晴れ(Satsuki-Bare)" and "五月雨(Samidare)". These refer to "sunny weather during the rainy season" and "rain during the rainy season", respectively. Both phrases include the word

"5月(Go-gatsu: May)" in their Chinese characters. In 2024, heavy rainfall was forecast from mid-June to July in most areas. This is exactly the time of year as of this writing.

Hmm? Did you notice that? Yes, the actual rainy season is in June and July, despite the word "5月(Go-gatsu: May)" in the phrases. In the lunisolar calendar, "May" corresponds to around June-July in the solar calendar. This illustrates how there are many phenomena in the Japanese language where there is a discrepancy between words and the actual seasons.

The Old Way of Naming the Months

The same is true for the old way of naming the months. There are several instances where there is a discrepancy between what the Chinese characters mean and the actual seasons. However, if you have read the previous articles and understand the history, it makes sense, and you can even enjoy learning about the differences between the words and the seasons. The etymology of each month is also explained, although there are many theories.

睦月(Mutsuki) - January: The month in which relatives gather to spend the New Year in close friendship. The name comes from the word "睦まじい(Mutsumajii)", meaning close and friendly.

如月 (Kisaragi) - February: The month in which the New Year is celebrated. Although it is officially spring according to the calendar, people put on more layers of clothing due to the continuing cold weather. Some believe that the name comes from "衣更着(Kisaragi)", meaning "to put on more clothes".

弥生 (Yayoi) - March: The month in which plants and trees finally start to grow. It represents the beginning of activity for plants and animals after a long winter.

卯月 (Uzuki) - April: The month in which the deutzia flower blooms. This flower typically blooms from May to June, signalling early summer, although this timing is slightly out of sync with the present day. In modern Japan, April marks the beginning of the new school term. Nowadays, people sense the season by looking at the cherry blossoms instead of the deutzia flower.

皐月 (Satsuki) - May: The month in which raised seedlings are planted in the rice paddies. Seedlings at this time are called 早苗(Sanae), so some people believe that "Satsuki" means 早苗("Sa"nae)の月(”Tsuki"), "the month of seedlings."

水無月 (Minazuki) - June: "無(Na)" in 水無月(Minazuki) means the Japanese particle "の(no)" and refers to "水の月(the month of water)". In other words, it is the month in which the rice fields are watered. According to some theories, it refers to July in the lunisolar calendar and originates from the fact that this was the time when the rainy season ended, and the rice fields were filled with water.

文月 (Fumizuki) - July: The month in which people write poems and wishes on 短冊(tanzaku: paper strips) and enjoy writing, particularly during 七夕(Tanabata festival). This event originated in China around the 8th century and was integrated into Japanese culture.

葉月 (Hazuki) - August: The month in which the leaves begin to fall. In modern August, the leaves are still firmly in place, but in the lunisolar calendar, it corresponds to September, when the leaves start to fall.

In Singapore, there is the Hungry Ghost Festival, and in Japan, there is お盆(Obon), an event to welcome and send off the spirits of ancestors.

長月 (Nagatsuki) - September: The month in which autumn gradually begins to take hold and the nights become longer. In regions influenced by Chinese culture, this is the month of the Mid-Autumn Festival. In Japan, people also look at the full moon and eat moon cakes in a similar manner.

神無月 (Kannazuki) - October: Similar to 水無月(Minazuki) in June, the "無(Na)" here means "の(no)", so 神無月(Kannazuki) translates to "神の月(the month of gods)". This is because gods from all over the country gather at the 出雲大社(Izumo-Taisha shrine) for meetings on matchmaking.

霜月 (Shimotsuki) - November: The month of frost. This is the time of year when agricultural work is finished, and festivals are held across the country to give thanks for the harvest. In Japan, 23 November is also a public holiday known as Labor Thanksgiving Day. Holidays in Japan are closely related to historical traditions.

師走 (Shiwasu) - December: The month in which 師(Shi: master/ monk) is busy running around, indicating the busyness of the end of the year. Although this theory lacks much evidence, the end of the year is undoubtedly a busy time with various events such as cleaning up and expressing gratitude to those who have helped us. The name aligns well with the actual experience of this busy period.

Summary

I was surprised at how much I could learn about Japanese culture and history just by studying the calendar. Through this study, I gained a clearer and deeper understanding of words and customs that I had never questioned before because they were so commonplace. It is also significant that by living in a foreign country and being exposed to different cultures, I am now able to look at Japan objectively from the outside. If I had not been in multicultural Singapore, I might not have had the opportunity to study this subject.

Thank you for reading!