A brief mindfulness-based intervention (bMBI) to reduce teacher stress and burnout

概要

教師のストレスとバーンアウトは精神・心理的消耗とストレス関連の健康問題につながる。いくつかのポジティブな影響にもかかわらず、これまでのマインドフルネスに基づく介入は、方法論的に厳密な要素を組み込めず、そのような方法は危険だとの指摘にも関わらず大量に実践されてきた。本研究は、自記式報告によるストレス・燃え尽き・うつ病を軽減するための短期MBI (briefMBI、4セッション、合計6時間) の有用性を実証し、bMBIが生理機能への有害な影響から保護されることを示している。本研究は、有効性を高め、費用対効果を最大化するために介入量を減らす戦略を含むMBIの計画と実装に役立つと考えられる。

内容

教師はとてもストレスフルな職業 (Smith et al., 2000)コーピングの許容量を超えるとバーンアウトするさらに、生理学的な機能も壊れる情緒的消耗は教師の効力感を減らす (McCarthy et al., 2009)

教師の40%が5年以内に仕事を継続できなくなると見積もられている多くの教師への介入は、コーピングの増加、認知行動的介入によっている

しかし近年、Mindfullness-based interventions (MBIs) が有効であると気づかれてきた

特に教師の職業性ストレスを緩和しバーンアウト症状を低下させる

しかし効果の示された研究の大部分は支援時間が長く、潜在的に介入効果を抑制している可能性がある (Kingbeil & Renshaw, 2018)

生理学的な指標を検討しているものは少ない

したがって、短期間のbMBIの効果を (6時間) 自記式ストレス質問紙と生理学的反応 (cortisol awakening response) から検証する

教師のストレスとバーンアウト

およそ1/3の教師がストレスをあるいは過度のストレスを感じていると報告する (Geving, 2007; Collie et al., 2012)

ストレスには様々な種類があり、例えば日々のストレスで言えば、社会的ストレス (同僚、上司、親)、時間のプレッシャー (授業の準備、グランディング、テストのためにカリキュラムにしたがうこと)、そのたの仕事の要求 (意欲のなくなった学生への指導、教室の規律の調整)など

各タイプのストレスマネジメントのスキル習得によりストレスや苦痛が緩和され、満足度がまし、消耗も減る (De Jesus & Conboy, 2001; Richardson & Rothstein, 2008)

バーンアウトは、情緒的消耗、冷笑的態度 (feeling cynical)、いらだち、仕事へのネガティブな感情 (脱人格化)、自己効力感と生産性の低下で現れる

(これは、仕事のし過ぎなどよく言われる燃えつき症候群すなわちバーンアウトではなく、いわゆるストレス症候群の一側面のように感じられるがうつ病・抑うつとの異動は調べられていない

教師は自分の投資に見合うリターンがないと感じると、ネガティブな感情・心理・職業への否定的影響が生じる (van Horn et al., 1999)

(やはりポジティブフィードバックの欠如による

(社会人だから耐えなければならないという発想そのものが根本的に間違っている

(賃金の対価に労働力を提供しているので、それ以上のものを求める時点で奴隷契約になってしまう

慢性的ストレスとバーンアウトのコスト

慢性的なストレスは精神と身体の問題を促し、例えばうつ病、immune system functioningの低下、過食、認知的な加齢、がんにつながる (Zechmeister et al., 2008; Saleh & Shapiro, 2008; Cohen et al., 2007)

慢性的ストレスとバーンアウトは、アロスタティック・ロードのバイオマーカと関連する (Juster, 2011)

特にコルチゾールのCAR (起床直後と30分後の差) がアロスタティックロードのバイオマーカとなる可能性が提唱されており (Prussner et al., 1997; wust et al., 2009; Fries et al., 2009)、ストレス・バーンアウトの磁気式尺度と相関がある (Prussner et al, 1999; Moya-Albiol et al., 2010)

過度のストレスや慢性のストレスは、CARを38-75%のレンジ外にする (Fries et al., 2009)

教師の1/3は過度のストレスを感じており (Geving, 2007; Collie et al., 2012)、最大45%の教師はバーンアウトを経験することから教師のメンタルヘルスは公衆衛生の重要な課題である

マインドフルネス:理論と教師への介入

(マインドフルネスの「今ここ」という日本語の翻訳文は、何かのアンチテーゼを目的としており特定の集団を否定しこき下ろすつまらない意味が含まれ、専門性に著しく欠けるとともに、哲学的な意味を持たせてしまうので、まじめな人は以下を参考にして全く意味は異なることに注意してほしい

Mindfulness ("paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally"; Kabat-Zinn, 1994) は教師がストレスとバーンアウトを緩和するための高次の技術となりえる (Ancona & Mendelson, 2014)

マインドフルネスの理論は、Attentive Awareness ("the quality and duration of one's mind in the here and now"; Renshaw, 2012)、Receptive Attitude ("one's outlook toward and reaction to particular stimuli that arise in awareness and are attended to in the present moment"; Renshaw & O'Malley, 2014)、Intentionality ("One's deliberate cultivation of an attentive awareness that is characterized by a receptive attitude, as opposed to simply recognizing or taking advantage of such features of one's mind whenever the chance occurs"; Renshaw & O'Malley, 2014)/("the purpose for cultivating the mindfulness awareness"; Shapiro et al., 2006)

MBIは西洋で広がり、痛みのマネージメント、ストレスリダクション、情動制御、抑うつと不安の緩和、全般的な健康とウェルビーイングを向上させる (Kabat-Zinn, 2003; Plikington et al., 2005; Teasdale et al., 2000; Carmody & Bear, 2008; Grossman et al., 2004)

職場におけるMBIはストレスを緩和し、ウェルビーイングを増加させることが示されている (Escuriex & Labbe, 2011; Irving et al., 2009; Virgili, 2013)

(ここまで強く主張されていてなぜわが国では大々的に実践されないのだろうか、実践しないということは少なくともRCTによる検証を否定しているのだろうか、まだよくわからないので読む

教師へのマインドフルネストレーニングはポピュラーになってきている (Hwang et al., 2017)

(そうでしょうか、全然推奨している専門家をみませんが、、

基本構成要素は、瞑想あるいは身体的なヨガ、および注意に焦点を当てるトレーニングであり、教師の場合には、mindfu awareness practies、コンパッションが新たなスキルとして追加される (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; Harris et al., 2016)

MBIは小から中程度のストレス軽減効果がある

Ancona & Mendelson (2014) は短い時間で中程度の効果がある

11時間の接触で大きな効果の研究もある (Beshai et al., 2016)

ただし、ランダマイゼーションなど研究手続きに不備があるため、本研究では6時間のbMBIによる教師のストレスリダクションの効果を明らかにすることを目的とする

先行研究のうち、教師のバーンアウトへのMBIの効果を明らかにした研究は2つである (Flook et al., 2013; Roser et al., 2013)

ただし、先行研究でバーンアウトに効果のあるMBIは合計26-30時間の介入が必要であるため、短い期間で効果のある介入を開発する必要がある

また、生理学的な効果も求められているが、起床時のコルチゾールを測定したものは3つしかない (Flook et al., 2013; Harris et al., 2016; Roeser et al., 2013)

これらの介入では介入による起床時コルチゾールに変化はないが、対照群はストレスの指標となるCARの減少がみられたものが2つあった

すなわち、MBIはストレス・バーンアウトの予防効果があると考えられる現状である

本研究

教師へのMBIの研究では、一般的に肯定的な結果が得られているが、多くは効果の減衰や医原性の可能性がある負担の大きなモデルを取り入れている (Klingbeil & Renshaw, 2018)

また、ランダマイゼーションの欠落、短期介入の欠落、生理学的指標の欠落により、短期的なMBIの効果を検証しにくくなっている

本研究は、6時間のbMBIをセルフレポートのストレス症状及びCARによって無作為割り付け比較試験を用いて検証する

方法

対象者

本研究データは、アメリカ南東部の高校教師から収集

24名の研究参加者のうち、教師は18名、4人はガイダンスカウンセラー、1名は学校心理学者、1名は教頭であった

女性95.8%、白人91.7%、25歳から70歳 (平均年齢42.77歳)、京食歴は1-49年 (平均15.58年)、83%は修士号取得者、50%は過去にメンタルヘルスサービスを利用したことがあった

手続き

本研究は、無作為割り付け・ウェイトリストコントロールのデザインを使用

研究者は、介入実施半年前から校長と相談し関心、リクルート、実施時の障壁について話し合った

介入群・対照群には、各12名ずつ無作為に割り当て

全セッションは学校の行動で放課後に実施

介入群・対照群ともに教育単位を付与

介入:

本研究で用いたマインドフルネスプログラムは、16週にわたり、毎月1回90分のセッションが実施された

臨床的にトレーニングを受けた研究者2名によって内容は修正され、学部生を対象に試行された (このステップもよくわからないが

カリキュラムは、attentive awareness/receptive attitude/ intentionalityというマインドフルネス認知行動療法モデル (Renshaw & O'Malley, 20014) に準拠している

セッション1-3はこれら3原則に対応する (セッション1はattentive awareness)

追加の統合セッションは最終セッションに行われ、各構成要素がどのように関連しているか焦点を合わせた

参加者全員に、プログラムの要素を促進する個別のワークブックが配布された (教訓、日記の記入、ディスカッション)

セッションは第一・第二著者によって実施された

各セッションは、①前セッションの振り返り、②現在のawareness exercise、③各セッションのトピックとストレスマネージメントの自己制御に関するプレゼンテーション、④マインドフルネスのスキル (受容的態度など) をモデル化・操作・実践する時間、⑤オープンなグループディスカッション、⑥記録、⑦終わりのエクササイズ (漸進的筋弛緩法)

参加者は、セッション以外での実施を奨励するための「in-between-notes」への記入を求められた

カリキュラムはすべて教師向けに調整されており、ファシリテーターは参加者がプログラムの内容を個人生活と職業生活の双方に役立つよう探求を奨励した

アドヒアランスのようなプロセス評価も実施

測定内容:

全ての測定は、介入前後で実施

基本属性とメンタルヘルスサービス利用歴の有無は全員に確認

教師のストレス:

Teachers Stress Inventory (TSI; Fimian & Fastenau, 1990)

5件法のリッカート尺度

10下位尺度構造

時間のマネージメント (α = .71)、仕事関連ストレス (α=.64)、プロとしての苦痛 (α=.68)、規律と意欲 (α=.92)、プロフェッショナルな投資 (α=.59)、感情表現 (α=.90)、疲労の表出 (α=.83)、心血管症状の表出 (=.77)、胃腸症状の表出 (α=.76)、行動の表出 (α=.68)

教師のバーンアウト:

Maslach Burnout Inventory Educators Survey (MBI-DS; Malsach et al., 1996)

22項目、3下位尺度

情緒的消耗 (9項目; α=.80)、脱人格化 (5項目; α=.65)、個人的達成感の減少 (8項目; α=.83)

教師の心理学的苦痛

Symptom Assesment-45 (SA-45; Davidson et al., 1997)

患者さん以外の方々を対象に実施

45項目、5件法

不安、抑うつ、強迫、心身症、恐怖、敵意、対人感受性、精神病性、妄想を測定

本研究では、不安 (α=.68)、抑うつ (α=.88)を使用

教師のマインドフルネス

Five-Facet Mildfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2008)

39項目、5件法のリッカート尺度

Observing (α=.86)、Describing (α=.91)、Acting with Awareness (α=.79)、Non-reactivity (α=.93)、Nonjudgement of Inner Experience (α=.81)

コルチゾール反応

これまでの研究から、唾液中のコルチゾールは体内で分泌されるコルチゾールを正確に反映し、人間のストレス反応の生理学的指標となることが示唆されている (Scasseliati et al., 2012)

さらに、CARは、人間のストレス反応への信頼性が高く、侵襲性の低い内分泌マーカーとして検証されている

日内変動の影響を軽減できる

分析

サンプルの同質性と記述統計

まず、ランダム化の後、カイ二乗検定により、性別、年齢、人種、経験年数、教育水準、メンタルヘルスサービスの利用履歴を介入群と対照群で比較

有意差が認められた場合はその後に共変量として分析

介入の実施前のアウトカムの同質性を担保するため、独立サンプルのt検定を実施

アウトカムとマインドフルネスの相関分析 (共変関係の担保)

bMBIの効果

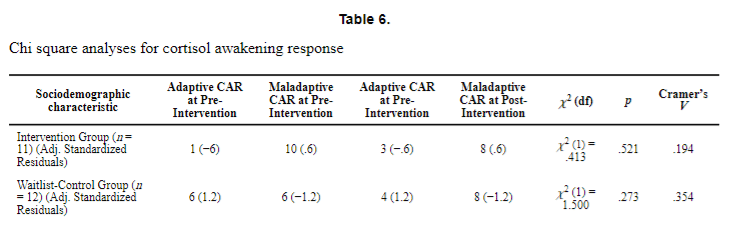

コルチゾール反応は、適応的 (CARが38-75%; Pruessner et al., 1997; Fries et al., 2009)、あるいは非適応的 (上記の反応を上回る・下回る反応) に分類

介入群と対照群において、adaptive/maladaptiveの変化をカイ二乗検定で検討

介入前後の変化量は、Cramer's Vで検討

ただし、検定で抽出されない傾向も明らかにするため定性レベルでも分析

結果

記述統計

基本属性には群間差なし

CARには群間差があり、介入群は介入前に不適応的なCARが多い

介入後は、マインドフルネス (FFMQ) と教師ストレス (r=-.530, p=.009)、バーンアウト (r=-.428,p=.042)に相関が認められたが、整理指標 (CAR, GSI of the SA-45) とは相関が認められなかった

下位尺度ではNonjudgment が教師の心理的ストレス (-.522,p=.006)、Non-reactivityが教師ストレス (-.602, p=.002)と関連

bMBIのストレスとバーンアウト低減効果

コルチゾール反応 (CAR)

カイ二乗検定では介入群の効果は認められなかったが、クラメールのVで小さい効果あり (3名が不適応→適応/1名が適応→不適応)

カイ二乗検定では対照群の効果は認められなかったが、クラメールのVで中程度の効果あり (3名が適応→不適応/1名が不適応→適応)

したがって、介入群ではCARの改善傾向・対照群ではCARの悪化傾向が認められる (統計学的有意差はなし)

自記式ストレス反応

教師ストレス尺度 (フルスケール) は、介入群で低下、対照群は変化なし

タイムマネージメント、仕事関連ストレス、Professional Distress、Professional Investment、疲労において改善が認められた

バーンアウト

介入群はバーンアウト (合計得点) の症状が緩和されたが、対照群は影響なし

介入群は、バーンアウトのEmotional Exaustion、Depersonalization、Personal Accomplishmentにおいて症状が緩和されたが、対照群は影響なし

教師の心理学的苦痛

SA-45 (抑うつ) は介入群で軽減したが、対照群に変化なし

SA-45 (不安) は介入群・対照群ともに変化なし

考察

bMBIは、90分*4=6時間の介入で効果が認められた

文献

Ancona, M. R., & Mendelson, T. (2014). Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a yoga and mindfulness intervention for school teachers. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 7(3), 156-170.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., ... & Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329-342.

Beshai S, McAlpine L, Weare K, Kuyken W (2016). A non-randomized feasibility trial assessing the efficacy of a mindfulness-based intervention for teachers to reduce stress and improve well-being. Mindfulness, 7(1), 198–208.

Carmody J, & Baer RA (2008). Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31, 23–33.

Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, & Miller GE (2007). Psychological stress and disease. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 298(14), 1685–1687.

Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2012). School climate and social–emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of educational psychology, 104(4), 1189.

Davison ML, Bershadsky B, Bieber J, Silversmith D, Maruish ME, & Kane RL (1997). Development of a brief, multidimensional, self-report instrument for treatment outcomes assessment in psychiatric settings: Preliminary findings. Assessment, 4(3), 259–276.

De Jesus, S. N., & Conboy, J. (2001). A stress management course to prevent teacher distress. International Journal of Educational Management, 15(3), 131-137.De Jesus, S. N., & Conboy, J. (2001). A stress management course to prevent teacher distress. International Journal of Educational Management, 15(3), 131-137.

Escuriex, B. F., & Labbé, E. E. (2011). Health care providers’ mindfulness and treatment outcomes: A critical review of the research literature. Mindfulness, 2, 242-253.

Fimian, M. J., and Fastenau, P. S. (1990). The validity and reliability of the Teacher Stress Inventory: A re-analysis of aggregate data. Journal of Organizational Behavior 11:151–57.

Flook L, Goldberg SB, Pinger L, Bonus K, & Davidson RJ (2013). Mindfulness for teachers: A pilot study to assess effects on stress, burnout, and teaching efficacy. Mind, Brain, and Education, 7, 182–195.

Fries E, Dettenborn L, & Kirschbaum C (2009). The cortisol awakening response (CAR): facts and future directions. International journal of Psychophysiology, 72(1), 67–73.

Geving, A. M. (2007). Identifying the types of student and teacher behaviours associated with teacher stress. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(5), 624-640.

Grossman P, Neimann L, Schmidt S, & Walach H (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57, 35–43.

Harris, A. R., Jennings, P. A., Katz, D. A., Abenavoli, R. M., & Greenberg, M. T. (2016). Promoting stress management and wellbeing in educators: Feasibility and efficacy of a school-based yoga and mindfulness intervention. Mindfulness, 7, 143-154.

Hwang, Y. S., Bartlett, B., Greben, M., & Hand, K. (2017). A systematic review of mindfulness interventions for in-service teachers: A tool to enhance teacher wellbeing and performance. Teaching and Teacher Education, 64, 26-42.

Irving JA, Dobkin PL, & Park J (2009). Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: A review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 15, 61–66.

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of educational research, 79(1), 491-525.

Juster RP, Sindi S, Marin MF, Perna A, Hashemi A, Pruessner JC, & Lupien SJ (2011). A clinical allostatic load index is associated with burnout symptoms and hypocortisolemic profiles in healthy workers. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36(6), 797–805.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2023). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hachette UK.

Klingbeil DA, & Renshaw TL (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for teachers: A meta-analysis of the emerging evidence base. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(4), 501.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, & Leiter MP (1996). Maslach burnout inventory manual (3 rd ed.). Mountain View, California: CPP, Inc.

McCarthy CJ, Lambert RC, O’Donnell M, & Melendres LT (2009). The relation of elementary teachers’ experience, stress, and coping resources to burnout symptoms. Elementary School Journal, 109, 282–300.

Moya‐Albiol, L., Serrano, M. Á., & Salvador, A. (2010). Burnout as an important factor in the psychophysiological responses to a work day in teachers. Stress and Health, 26(5), 382-393.

Pilkington K, Kirkwood G, Rampes H, & Richardson J (2005). Yoga for depression: the research evidence. Journal of affective disorders, 89(1–3), 13–24.

Pruessner JC, Gaab J, Hellhammer DH, Lintz D, Schommer N, & Kirschbaum C (1997). Increasing correlations between personality traits and cortisol stress responses obtained by data aggregation. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 22(8), 615–625.

Pruessner JC, Gaab J, Hellhammer DH, Lintz D, Schommer N, & Kirschbaum C (1997). Increasing correlations between personality traits and cortisol stress responses obtained by data aggregation. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 22(8), 615–625.

Pruessner JC, Hellhammer DH, & Kirschbaum C (1999). Burnout, perceived stress, and cortisol responses to awakening. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61(2), 197–204.

Renshaw TL (2012). Mindfulness-based practices for crisis prevention and intervention. In Brock SE & Jimerson SR (Eds.), Handbook of school crisis prevention and intervention (2 nd ed., pp. 401–422). Bethesda, MA: National Association of School Psychologists.

Renshaw TL, & O’Malley MD (2014). Cultivating mindfulness in students. In Furlong MJ, Gilman R,

& Huebner ES (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology in the schools (2nd ed., pp. 245–259).

New York, NY: Routledge.Richardson KM, & Rothstein HR (2008). Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: a meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(1), 69.

Roeser RW, Schonert-Reichl KA, Jha A, Cullen M, Wallace L, Wilensky R, ...Harrision J (2013). Mindfulness training and reductions in teacher stress and burnout: Results from two randomized, waitlist-control field trials. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 1–18.

Saleh P & Shapiro CM (2008). Disabled sleep and burnout: implications for long-term health. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 65, 1–3

Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, & Freedman B (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of clinical psychology, 62(3), 373–386.

Taylor, S. G., Roberts, A. M., & Zarrett, N. (2021). A brief mindfulness-based intervention (bMBI) to reduce teacher stress and burnout. Teaching and Teacher Education, 100, 103284.

Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Ridgeway VA, Soulsby JM, & Lau MA (2000). Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 68(4), 615.

Van Horn, J. E., Schaufeli, W. B., & Enzmann, D. (1999). Teacher burnout and lack of reciprocity 1. Journal of applied social psychology, 29(1), 91-108.

Virgili, M. (2015). Mindfulness-based interventions reduce psychological distress in working adults: a meta-analysis of intervention studies. Mindfulness, 6(2), 326-337.

Wust, S., Wolf, J., Hellhammer, D. H., Federenko, I., Schommer, N., & Kirschbaum, C. (2000). The cortisol awakening response-normal values and confounds. Noise and health, 2(7), 79-88.

Zechmeister I, Kilian R, & McDaid D (2008). Is it worth investing in mental health promotion and prevention of mental illness? A systematic review of the evidence from economic evaluations. BMC public health, 8(1), 20.

Appendix-A: Teacher Stress Inventory

1=No Strength; not noticeable; not applicable

2=Mild Strength; barely noticeable

3=Medium Strength; moderately noticeable

4=Great Strength; very noticeable

5=Major Strength; extremely noticeable

1. There is little time to prepare for my lessons/responsibilities.

2. My personal priorities are being shortchanged due to time demands.

3. I have too much work to do.

4. My caseload/class is too big.

5. The pace of the school day is too fast.

6. There is too much administrative paperwork in my job.

7. I lack promotion and/or advancement opportunities.

8. I am not progressing in my job as rapidly as I would like.

9. I need more status and respect on my job.

10. I lack recognition for the extra work and/or good teaching I do.

11. My personal opinions are not sufficiently aired.

12. I receive an inadequate salary for the work I do.

13. I lack control over decisions made about classroom/school matters.

14. I am not emotionally/intellectually stimulated on the job.

15. I lack opportunities for professional improvement.

I feel frustrated . . .

16. having to monitor pupil behavior.

17. because of discipline problems in my classroom.

18. attempting to teach students who are poorly motivated.

19. because some students would do better if they tried harder.

20. because of inadequate/poorly defined discipline policies.

21. when my authority is rejected by pupils/ administration.

I respond to stress . . .

22. by feeling insecure.

23. by feeling unable to cope.

24. by feeling vulnerable.

25. by feeling depressed.

26. by feeling anxious.

27. by calling in sick.

28. by using prescription drugs.

29. by using over-the-counter drugs.

30. with rapid and/or shallow breath.

31. by using alcohol.

32. with feeling increased blood pressure.

33. with feelings of heart pounding or racing.

34. with stomach pain of extended duration.

35. with stomach cramps.

36. with physical exhaustion.

37. with physical weakness.

38. by becoming fatigued in a very short time.

39. with stomach acid.

40. by sleeping more than usual.

41. by procrastinating.

42. I rush in my speech.

43. There isn’t enough time to get things done.

44. I have to try doing more than one thing at a time.

45. I become impatient if others do things too slowly.

46. I have little time to relax and enjoy the time of day.

47. I easily overcommit myself.

48. I think about unrelated matters during conversations.

49. I feel uncomfortable wasting time.

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?