CEFR(2020)の邦訳ゲーテインスティテュート(2023)からの引用など

CEFR(2020)の邦訳ゲーテインスティテュート(2023)から

第2章 教授と学習にとって重要なCEFRの考え方

CEFR(The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment、CEFR(2001))は、言語運用能力を包括的に記述する体系と、能を記述によって能力を例示する形で規定した(defined in illustrative descriptor scales)共通参照レベル(A1からC2までの6段階)を提示しています。さらに、CEFRでは、複言語・異文化間教育を振興するためのカリキュラムデザインのいくつかの選択肢も提案されています。カリキュラムデザイン関係については、『複言語・異文化間教育のカリキュラムの開発と実践のための指針』(Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and intercultural education、Beacco et al. 2016a)さらに詳しく論じられています。

CEFRの大原則の一つは、すべての教育レベルにおいて、教育の目標と成果を肯定的に記述することを奨励することです。「〜できる」(Can-do)という形で言語運用能力のさまざまな側面を規定することで、明快で共有可能な学習のロードマップと、言語の上達を測って見せるひじょうに優れた評価法を提供することができます。その評価法は、学校のテストや言語標準テストの結果の点数にのみ目を向ける評価法よりもずっと細かく個々の学習者の運用能力を示すことができます。

この原則はCEFRが、言語を社会や教育や職業の領域で機会を得て成功を収めるための道具であると考えていることに基づいています。欧州評議会ではすべてのヨーロッパ市民がその権利として質の高いインクルーシブな教育が受けられることを目標にしていますが、CEFRの上述の基調的な考えはその目標の達成に寄与するものです。欧州評議会の大臣会議も「民主的な市民性と社会的結束 と文化間の対話を進める形で一貫性のある透明で有効な複言語教育を振興するための道具としてCEFRを活用すること」を推奨しています。(邦訳p.7)

Chapter 2 KEY ASPECTS OF THE CEFR FOR TEACHING AND LEARNING p.27

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR) presents a comprehensive descriptive scheme of language proficiency and a set of Common Reference Levels (A1 to C2) defined in illustrative descriptor scales, plus options for curriculum design promoting plurilingual and intercultural education, further elaborated in the Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and intercultural education (Beacco et al. 2016a).

One of the main principles of the CEFR is the promotion of the positive formulation of educational aims and outcomes at all levels. Its “can do” definition of aspects of proficiency provides a clear, shared roadmap for learning, and a far more nuanced instrument to gauge progress than an exclusive focus on scores in tests and examinations. This principle is based on the CEFR view of language as a vehicle for opportunity and success in social, educational and professional domains. This key feature contributes to the Council of Europe’s goal of quality inclusive education as a right of all citizens. The Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers recommends the “use of the CEFR as a tool for coherent, transparent and effective plurilingual education in such a way as to promote democratic citizenship, social cohesion and intercultural dialogue”.(p.27)

CEFRの背景

CEFRは70年代から80年代に欧州評議会が行ってきた言語教育関係の仕事を発展的に継承しています。“Threshold Level”の公表で1970 年半ばにコミュニカティヴ・アプローチが提案されました。“Threshold Level”では言語活動のニーズが初めて機能と概念の観点から特定されました。CEFRの「行動主義的なアプローチ」は、そのコミュニカティヴ・アプローチを引き継ぎ、さらに推し進めるものです。

CEFR とそれに関連して随伴するEuropean Language Portfolio(ELP:ヨーロッパ言語ポートフォリオ)は1991年にスイスで開催された政府間シンポジウムで推奨されました。その副題が示しているように、CEFRは主として学習と教授に関連しています。その目的は、カリキュラムと教授と評価相互の透明性と一貫性を一つの機関の内部で促進するとともに、同様の透明性と一貫性を機関と機関の間で、教育部門間で、そして地域や国家間で促進することです。CEFRは2001年の英語版(Cambridge University Press)が出版される前に、1996年と1998年の準備稿に基づいて試行されています。(邦訳p.7のコラム)

Background to the CEFR

The CEFR was developed as a continuation of the Council of Europe’s work in language education during the 1970s and 1980s. The CEFR “action-oriented approach” builds on and goes beyond the communicative approach proposed in the mid-1970s in the publication “The Threshold Level”, the first functional/notional specification of language needs. The CEFR and the related European Language Portfolio (ELP) that accompanied it were recommended by an intergovernmental symposium held in Switzerland in 1991. As its subtitle suggests, the CEFR is concerned principally with learning and teaching. It aims to facilitate transparency and coherence between the curriculum, teaching and assessment within an institution and transparency and coherence between institutions, educational sectors, regions and countries. The CEFR was piloted in provisional versions in 1996 and 1998 before being published in English (Cambridge University Press).(p.27)

2.1 CEFRのねらい

CEFRは欧州評議会のプロジェクトが教育改革に与えてきた改革推進の力を継続させようとするものです。CEFR は言語専門家が学習と教授の質と有効性をさらに高めるのを支援することをめざしています。副題の「学習、教授、評価」という語順ではっきり示されているように、CEFR は評価に焦点を当てているわけではありません。

CEFRはコミュニケーションの仲立ちとしての言語の教授と学習を発展させるだけでなく、学習者をエンパワーするという新しい見方を提示しています。すなわち、CEFRでは言語使用者/学習者を「社会的存在 」(social agent)として提示しています。「社会的存在」というのは、人と人が交わる実世界で行動して学習の過程で主体性を発揮する者ということです。したがって、この新しい見方には、学習者による活動従事(engagement)と学習者の自律性(autonomy)を促進するという形でコース企画と教授の両方面で実際にパラダイムシフトが起こることが当然伴っています。

CEFRの行動中心のアプローチは、言語構造の学習が積み上げ式に進行するシラバスやあらかじめ決められた概念と機能に基づくシラバスから脱却して、ニーズ分析に基づき、実生活で実際に遭遇するさまざまな課題の遂行に向け、はっきりとした目的の下に選ばれた概念と機能をめぐって構築されるシラバスに移行することを表明しています。シラバスのこうしたシフトは、学習者がまだ身につけていないものに焦点を当てる「足りないものを足していく」という見方(“deficiency” perspective)ではなく、むしろ、“can-do”記述文を導きとして「できるようになっていく」という見方(“proficiency-perspective” perspective)広めるでしょう。新しいシラバスの考え方は、実世界でのコミュニケーションの必要性に基づき、実生活で実際に遭遇する諸課題をめぐって組織化し、学習者にねらいをはっきりと伝える「can-do」記述文を用意してカリキュラムやコースをデザインするということです。CEFRは、基本的に、言語使用者/学習者がその言語でできるようになるべきことから逆算してカリキュラムやコースや試験を企画することを支援するツールです。CEFR(2001)の第4章と第5章では、利用可能と見られる限り多くの面についての例示的な“can-do”能力指標(illustrative “can do” descriptor scales)を含む包括的な能力記述スキームを提供していましたし、さらにさまざまな言語についてそれぞれで公表されている関連のレベル別内容特定一覧表(Reference Level Descriptions: RLDs)もあります。それらはいずれも、上述のように教育を企画するための基礎資料を提供することを狙ったものです。(邦訳p.8)

2.1. AIMS OF THE CEFR

The CEFR seeks to continue the impetus that Council of Europe projects have given to educational reform. The CEFR aims to help language professionals further improve the quality and effectiveness of language learning and teaching. The CEFR is not focused on assessment, as the word order in its subtitle – Learning, teaching, assessment – makes clear.

In addition to promoting the teaching and learning of languages as a means of communication, the CEFR brings a new, empowering vision of the learner. The CEFR presents the language user/learner as a “social agent”, acting in the social world and exerting agency in the learning process. This implies a real paradigm shift in both course planning and teaching by promoting learner engagement and autonomy.

The CEFR’s action-oriented approach represents a shift away from syllabuses based on a linear progression through language structures, or a pre-determined set of notions and functions, towards syllabuses based on needs analysis, oriented towards real-life tasks and constructed around purposefully selected notions and functions. This promotes a “proficiency” perspective guided by “can do” descriptors rather than a “deficiency” perspective focusing on what the learners have not yet acquired. The idea is to design curricula and courses based on real-world communicative needs, organised around real-life tasks and accompanied by “can do” descriptors that communicate aims to learners. Fundamentally, the CEFR is a tool to assist the planning of curricula, courses and examinations by working backwards from what the users/learners need to be able to do in the language. The provision of a comprehensive descriptive scheme containing illustrative “can do” descriptor scales for as many aspects of the scheme as proves feasible (CEFR 2001 Chapters 4 and 5), plus associated content specifications published separately for different languages (Reference Level Descriptions – RLDs)22 is intended to provide a basis for such planning.

2.2 行動中心のアプローチの具体化

CEFRは当初より包括的で中立的であることを旨としています。包括的というのは、言語教育の主要な諸アプローチをそこに見出すことができるという意味です。そして、中立的というのは、さまざまな問題について答えを出すというよりもむしろ問いかけをするし、いかなる特定の教育方法も提唱するわけではないという意味です。例えば、文法や文学を教えることをやめるべきだなどとは決して言っていません。また、学習者の学習の進歩をどう評価するのが一番いいかについての「正しい答え」も出していません。しかしながら、CEFRは学習者を言語使用者としてまた社会的存在として見ることで革新的なスタンスを採っていますし、そのことで言語を学習の対象としてよりもむしろコミュニケーションの仲立ちとしている見るスタンスを採っています。そうしたスタンスを採って、学習者ニーズを分析することと、「can-do」記述文とコミュニケーション課題(communicative tasks)を使用することを提案しています。そして、そのテーマに一つの章が割かれています。第7章です。

CEFRの教育方法についての考えは、言語の学習を学習者が実生活のさまざまな状況で自分の考えを表現しさまざまな課題を遂行して行動できるようにすることに向けるべきだということです。こうした考えから、評価の基準は、実生活におけるコミューション能力を一連の能力発達の経路として示したもの(A1レベルからC2レベル)となりました。これは「規準準拠的評価」でいう「規準」の本来的な意味です。CEFR( 2001)の第4章と第5章の能力記述文はカリキュラムのねらいと標準および評価規準を明瞭に規定しようとする際の基盤となります。第4章では言語活動つまり「何が(できるようになるのか)」に重点をおき、第5章では能力つまり「どのように(できるか)」に焦点を置いています。CEFRはこの点では教育的に中立的だとは言えません。これは、教授と学習の過程が行動することで進められることを意味します。つまり行動中心主義です。それはまた、学習者の実生活のコミュニケーションの必要性から逆算して計画するべきことを明らかに提案しています。その際に、カリキュラムと教授と評価の3者がしっかり連携するべきことは言うまでもありません。

授業のレベルでも、行動中心のアプローチを実施することの意味がいくつかあります。学習者を「社会的存在」と見ることは、おそらくは能力記述文を学習者とのコミュニケーションの手段として、学習者を学習という活動に巻き込むことを意味します。また、行動中心のアプローチには、言語の学習を言語の行使は人と人の間で行われるという性質があると認識することを含んでいます。つまり、学習の過程で社会と個人が相互作用するということです。学習者を言語使用者と見るというのは、授業で広範に目標言語を使用することを意味します。つまり、ただ言語について(教科として)学ぶのではなくむしろ言語を使うことを学ぶのです。学習者を複言語・複文化的存在として見ることは、必要に応じてかれらがもつすべての言語リソースを利用することを許し、言語間や文化間の違いだけでなく類似点や規則性を見出すように促すことを意味します。何よりも、行動中心のアプローチでいくというのは、主な関心が言語にはなく、目的が設定された協働的な課題を実施することを意味します。課題の第一の焦点が言語でないとするなら、そこでは、言語以外の産物や産出物の設定が要請されます。例えば、遠足の計画、ポスターの制作、ブログ作成、お祭りの計画、候補者の選択などです。能力記述文は、そのような課題をデザインするのに役立つでしょうし、課題に取り組み中の学習者の言語使用の状況を観察したり、望むならば、評価したり、学習者が自己評価したりするのにも役立つででしょう。

能力を記述するというCEFRの新たな計画と行動中心のアプローチは、(相互行為を通して)意味を協働的に構築することを学習と教授の過程の中心に据えます。このことには、授業をめぐって直接的な示唆があります。相互行為は、教師と学習者の間で行われることもあるでしょうし、学習者同士で、つまり協働的なものとなることもあるでしょう。教師中心の授業とこうした小グループでの学習者同士の協働的な相互行為の間のバランスは場合によって異なるでしょう。つまり、当該教育の文脈となっている教育的伝統や学習者の熟達度レベルによって異なるでしょう。また、ますます多様化していく現在の社会という現実を鑑みるなら、意味の構築は複数の言語横断的に行われ、使用者/学習者が有する複文化・複言語的なレパートリーを引き出すこともあるでしょう。

2.2. IMPLEMENTING THE ACTION-ORIENTED APPROACH

The CEFR sets out to be comprehensive, in the sense that it is possible to find the main approaches to language education in it, and neutral, in the sense that it raises questions rather than answering them and does not prescribe any particular pedagogic approach. There is, for example, no suggestion that one should stop teaching grammar or literature. There is no “right answer” given to the question of how best to assess a learner’s progress. Nevertheless, the CEFR takes an innovative stance in seeing learners as language users and social agents, and thus seeing language as a vehicle for communication rather than as a subject to study. In so doing, it proposes an analysis of learners’ needs and the use of “can do” descriptors and communicative tasks, on which there is a whole chapter: CEFR 2001 Chapter 7.

The methodological message of the CEFR is that language learning should be directed towards enabling learners to act in real-life situations, expressing themselves and accomplishing tasks of different natures. Thus, the criterion suggested for assessment is communicative ability in real life, in relation to a continuum of ability (Levels A1-C2). This is the original and fundamental meaning of “criterion” in the expression “criterion-referenced assessment”. Descriptors from CEFR 2001 Chapters 4 and 5 provide a basis for the transparent definition of curriculum aims and of standards and criteria for assessment, with Chapter 4 focusing on activities (“the what”) and Chapter 5 focusing on competences (“the how”). This is not educationally neutral. It implies that the teaching and learning process is driven by action, that it is action-oriented. It also clearly suggests planning backwards from learners’ real-life communicative needs, with consequent alignment between curriculum, teaching and assessment.

29

At the classroom level, there are several implications of implementing the action-oriented approach. Seeing learners as social agents implies involving them in the learning process, possibly with descriptors as a means of communication. It also implies recognising the social nature of language learning and language use, namely the interaction between the social and the individual in the process of learning. Seeing learners as language users implies extensive use of the target language in the classroom – learning to use the language rather than just learning about the language (as a subject). Seeing learners as plurilingual, pluricultural beings means allowing them to use all their linguistic resources when necessary, encouraging them to see similarities and regularities as well as differences between languages and cultures. Above all, the action-oriented approach implies purposeful, collaborative tasks in the classroom, the primary focus of which is not language. If the primary focus of a task is not language, then there must be some other product or outcome (such as planning an outing, making a poster, creating a blog, designing a festival or choosing a candidate). Descriptors can be used to help design such tasks and also to observe and, if desired, to (self-)assess the language use of learners during the task.

Both the CEFR descriptive scheme and the action-oriented approach put the co-construction of meaning (through interaction) at the centre of the learning and teaching process. This has clear implications for the classroom. At times, this interaction will be between teacher and learner(s), but at times, it will be of a collaborative nature, between learners themselves. The precise balance between teacher-centred instruction and such collaborative interaction between learners in small groups is likely to reflect the context, the pedagogic tradition in that context and the proficiency level of the learners concerned. In the reality of today’s increasingly diverse societies, the construction of meaning may take place across languages and draw upon user/learners’ plurilingual and pluricultural repertoires.

2.3 複言語・複文化能力

CEFRは多言語(さまざまな言語が社会あるいは個人のレベルで共存している状況)と複言語(個々の使用者/学習者において言語レパートリーがダイナミックに発展している状況)とを区別しています。複言語はCEFRの中では均一でない変化し続ける能力として位置づけられています。そして、その能力では、言語使用者/学習者の中の一つの言語あるいはその変種のリソースは別の言語のリソースとは大きく異なる場合もあります。しかしながら、重要な点は、複言語話者は、相互に関連しているが単一のレパートリーをもっているということです。そして、複言語話者はそのレパートリーをさまざまな一般的能力とさまざまな方略に結びつけてさまざまな課題を実行します。(CEFR(2001) 6.1.3.2)

The CEFR distinguishes between multilingualism(the coexistence of different languages at the social or individual level)and plurilingualism (the dynamic and developing linguistic repertoire of an individual user/learner). Plurilingualism is presented in the CEFR as an uneven and changing competence, in which the user/learner’s resources in one language or variety may be very different in nature from their resources in another. However, the fundamental point is that plurilinguals have a single, interrelated, repertoire that they combine with their general competences and various strategies in order to accomplish tasks (CEFR 2001 Section 6.1.3.2).

2.4 CEFRの記述スキーム

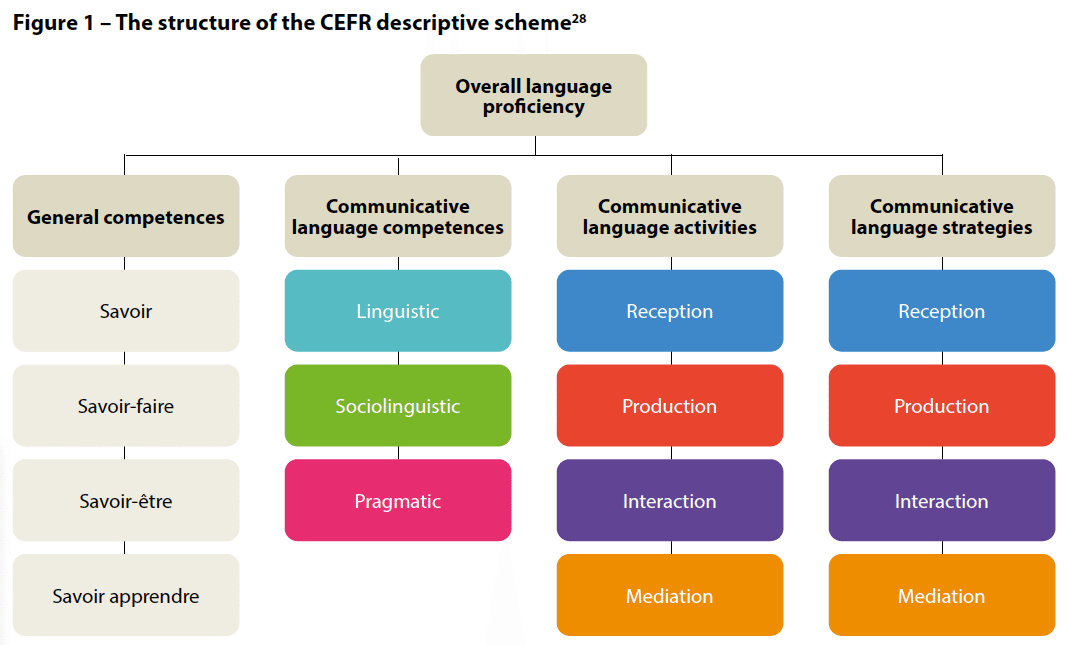

この節ではCEFRの記述スキームを概観し、どの点が2014~17年のプロジェクトでさらに開発されたかを指摘します。上で述べたようにCEFRのねらいの核は、言語熟達度について議論するための共通のメタ言語的な語り方を提示することです。図1がそのCEFRの記述の構成を示しています。

関連する重要概念の紹介(CEFR(2001)第1章)に続いてCEFRのアプローチがひじょうに短い第2章で紹介されています。どんなコミュニケーションの状況でも、課題を達成するために、一般能力(例えば、世界知、社会文化的能力、異文化能力、もし持っているなら専門的経験、CEFR(2001) 5.1)は常に言語コミュニケーション能力(言語能力、社会言語的能力、語用論的能力、CEFR 2001 5.2)といろいろな方略(いくつかの一般的方略といくつかの言語コミュニケーション的方略)と結びつけられます(CEFR(2001)第7章)。課題の達成が他者との協働を要請する場合、したがって言語でコミュニケーションすることを要請する場合もしばしばあります。第2章で選ばれたこの考えを紹介するための例 ―引っ越し―は言語使用がまさに課題次第で決まってくる例です。タンスを動かす際には、何らかのコミュニケーションをすること―たいていは言語による―が明らかに推奨されます。しかし、言語が課題の主要な関心だというわけではありません。同様に、より込み入ったコミュニケーションを要求する課題、例えば道徳的な問題についての解決法をみんなで相談することや何らかのプロジェクトをめぐって会議をすることなどでも、焦点は課題を達成するために使われる言語よりむしろ結果におかれます。CEFRのアプローチの全体は、1つのパラグラフに要約することができます。

言語の行使には言語の学習が伴っています。そんな言語の行使は、人によって遂行される行為となっています。そして、そのように行為を遂行する当人は、個人として、そして同時に社会的主体として、一般能力(general competences)と特にコミュニケーション言語能力(communicative language competences)を含むさまざまな種類の能力を発達させます。人は、言語活動(language activities)に従事するために、さまざまな条件下のさまざまな文脈(context)の下で、そしてさまざまな制約の中で能力を活用します。そして、言語活動には、言語活動で達成するべき課題(task)を遂行するために最も適当と思われるストラテジー(strategies)を起動させつつ、特定の領域(domain)のテーマに関連したテキスト(text)を作成したり受け取ったりする言語プロセス(language processes)が伴います。これらの行動をモニターすることで、言語活動の当事者は能力を強化したり、知識を修正したりすることができます。(CEFR 2001 2.1)

このように、課題の遂行にあたっては、活動従事で能力と方略が動員され、そのように経験することで翻って能力と方略はさらに開発されます。「行動中心のアプローチ」はCEFRの能力記述のスキームを実際化しするものですが、そのアプローチでは教室で何らかの協働的課題を設定して実施することが必須となります。これがCEFR(2001)で課題について論じた章を立てている理由です。また、CEFR(2001)の第7章では、実生活での課題と教育的課題、両者の折衷の可能性、課題が言語的に簡単になったり複雑になったりする要因、そして課題にまつわる条件や制約について議論しています。授業で具体的にどのような課題を設定するか、コース内で課題をどの程度主導的位置とするかは、CEFRの利用者各々が決定すべきことです。

2.4 THE CEFR DESCRIPTIVE SCHEME

The overall approach of the CEFR is summarised in a single paragraph:

Language use, embracing language learning, comprises the actions performed by persons who as individuals and as social agents develop a range of competences, both general and in particular communicative language competences. They draw on the competences at their disposal in various contexts under various conditions and under various constraints to engage in language activities involving language processes to produce and/or receive texts in relation to themes in specific domains, activating those strategies which seem most appropriate for carrying out the tasks to be accomplished. The monitoring of these actions by the participants leads to the reinforcement or modification of their competences. (CEFR 2001 Section 2.1)

Thus, in performing tasks, competences and strategies are mobilised in the performance and in turn further developed through that experience. In an “action-oriented approach”, which translates the CEFR descriptive scheme into practice, some collaborative tasks in the language classroom are therefore essential. This is why the CEFR 2001 includes a chapter on tasks. CEFR 2001 Chapter 7 discusses real-life tasks and pedagogic tasks, possibilities for compromise between the two, factors that make tasks simple or complex from a language point of view, conditions and constraints. The precise form that tasks in the classroom may take, and the dominance that they should have in the programme, is for users of the CEFR to decide.

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?