“Shanghai of Saitama” Asaka, Jazz Umi

Neighbour: This is a place for women's business, not a place for music.

Owner: If you want to crush it, then do it.

The owner of Jazz Kissa Umi was intimidated by his neighbour when it opened in Showa 27 (1952). Asaka, northwest of Tokyo, was known as the ‘Shanghai of Saitama’ owing to its flourishing nightlife. Currently, a second-generation family business run by the owner’s son, Kazunori Komiya. Umi translates to sea, named so, as his father served in the navy.

I frequented Umi while volunteering to restore a bonsai garden in Saitama that was hit by the violent cyclone Typhoon Hagibis. As always, I hesitated about where to sit. The warm afternoon sunlight drew me to the window seats. Soon after I had put my bag down, my body navigated towards the counter to gaze at the sound systems, as if there was a magnetic force.

Synchronising with my curiosity, Komiya-san went into the sound system corner. With a white towel around his neck, he began to speak in a firm voice about the history of Asaka and the audio equipment behind him. Komiya-san’s wife said, “Take off the towel,” but he firmly grasped the ends of the towel, continuing the story.

Komiya-san recalled his youthful memories growing up in Asaka. Outside Umi, there were girls and yankees walking around; he remembered he was picking up jarasen (coins) outside the cafe while people were fighting. Since the post-war era, the American military base Camp Drake was located in Asaka until 1972. Stretching beyond the military fence, there were magnificent fields of grass, tennis and golf courses that he had never seen before. The side of the fence that he knew was just bumpy roads and carrot fields.

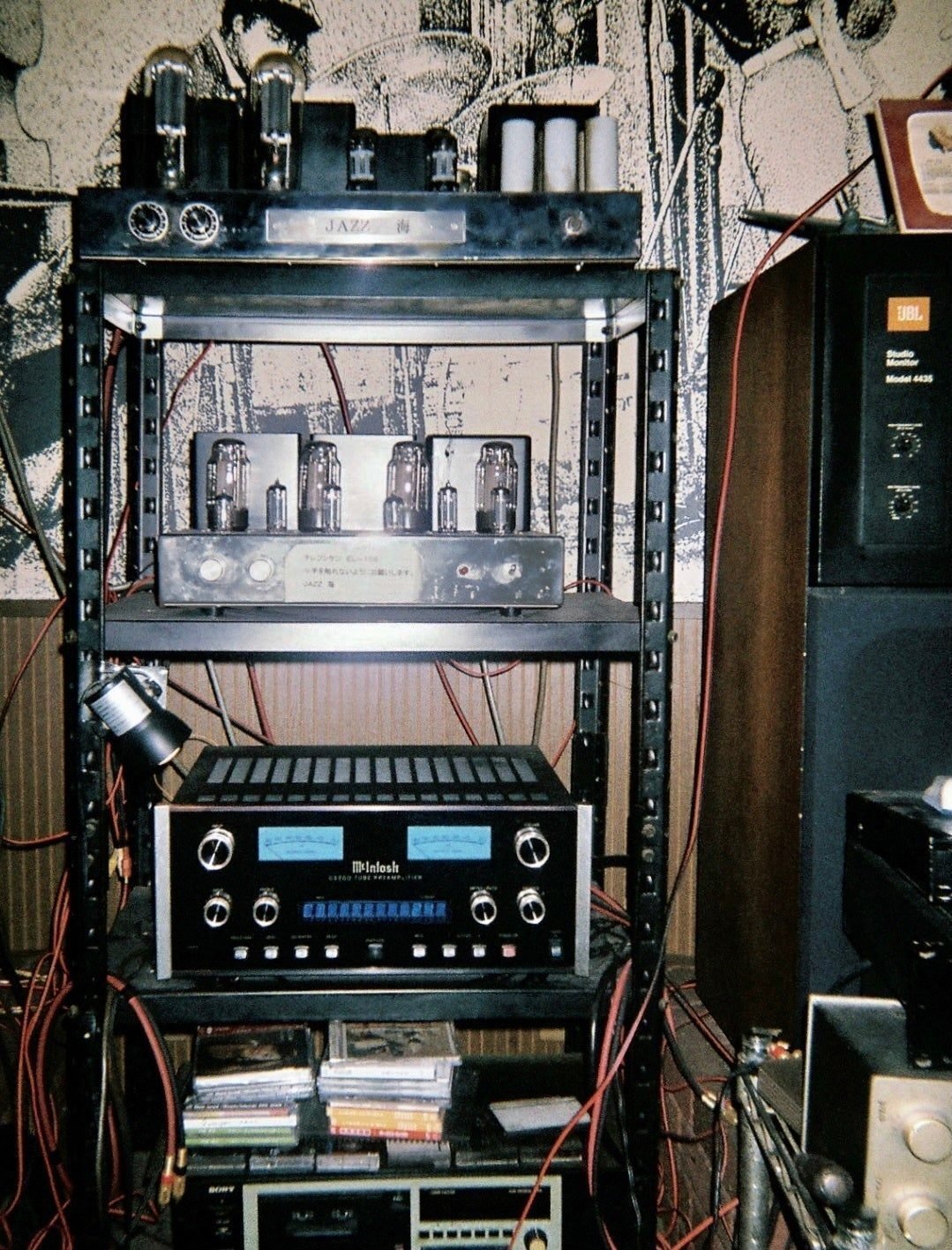

Umi’s signature Vacuum Tube Power Amp GE 211 was initially used in the army for communication purposes and later rebuilt for Umi by Arai Laboratory. I had the chance to listen to Telefunken EL156, which had to be heated up 20 minutes in advance. When he turned the speakers to their fullest potential, the piano tuner that sat beside me and I bursted out laughing since the sound was so powerful and every detail of the instruments was so flawless.

A year later, I visited Umi again after work on Christmas night. The conversation wavered between his ancestors, Edo Shogunate, to a sudden ghost story that popped out of nowhere.

Arai-sensei, the sound scientist behind Arai Laboratory, remains a crucial figure to Komiya-san. In his twenties, a customer came into Umi and introduced Arai-sensei’s systems to him. Back then, Komiya-san would finish work at midnight, bring records to his living room, and listen to FM Tokyo Jet Stream radio with Altec speakers. Paul Desmond’s alto saxophone sounded different as if he had been transported into another world. A thick sound came out from Arai-sensei’s amplifier as if it were live music.

Later, Komiya-san was invited to Arai-san’s workshop in a factory compound in Isesakishi, Gunma Prefecture. He drooled over the wall of Macintosh and Tannoy audio systems, which Arai-sensei called “Tannai” that Komiya-san humorously recalled. There, he listened to the String Quartet. At that moment, he understood that amplifiers are the heart of audio systems. He yearned for Arai-sensei’s amplifiers, but they were the price of a car. After a few discussions with his father, who loved records, he eventually obtained one.

Komiya-san proudly reminisced about his father throughout the several conversations I had with him. He was born in Nihonbashi, with a superb style, and spoke fluent English. From the beginning, his father adopted a casual and American style of jazz kissa, which differed from the stereotypical image of jazz kissa where people were prevented from talking. In the post-war era, the shops were separated into places for white and black people. However, at Umi, all were embraced. Komiya-san was fascinated by how, after the war, people could sit inside the same place listening to jazz when they cruelly fought against each other before the war. Komiya-san continues his father’s legacy and welcomes jazz lovers and sound enthusiasts worldwide.

“There are ghosts in the Asaka Forest,” said Komiya san.

“Ghosts?!”

“I’ll bring you next time. Haven't I told you about the ghost story?”

“What? Is this history? Maybe not today. Can we talk about it next time?”

“Do you know ghosts?”

“But it's Christmas today... Why do you have to tell me today? (with a trembling voice)”

“I told you, it’s history!”

Then, he told me the ghost story at last, leading on to another story. Afterward, he kindly drove me to the station on a shivering night. I took the train back to Tokyo to fetch my bike and returned home at midnight with an empty stomach.

Three years later, I visited Umi, “Is your foot okay now?” he asked me.

“???”

“I remember I gave you a ride to the station because you couldn’t walk. You didn’t turn on the heater in winter for the environment... how do you get frostbite in this era?”

“Oh right...” (Since 2018, every winter, my two toes are in pain. I learned the lesson the hard way – heater exists for a reason...)

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?