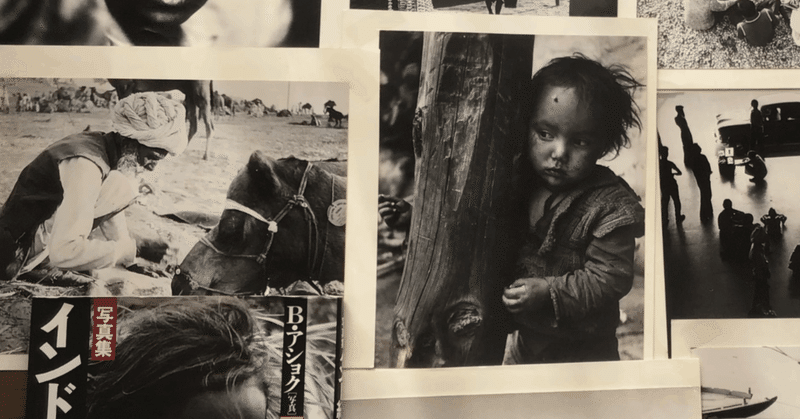

My love for the photographs of 1980’s India by B.Ashok

First published in RIC Journal, January 16, 2023

1.

It was in his room at the university hostel

where I saw for the first time his photos: portraits of

North Indian rural people.

Both of us were post graduate students at Jawaharlal Nehru University,

belonging to different schools.

His major was Spanish, and I studied in Centre for South Asian Studies.

We came to know each other through my classmate who was

from the same Southern state as he was.

Although a student of language, he was introduced to me

as a rather well-known photographer.

Actually, his photos had sometimes appeared in magazines or newspapers circulated in and around New Delhi, the capital of India.

“Saaranga” was one of those magazines.

It was launched in 1988

as a Hindi magazine for art and culture,

featuring his photographs in the first issue.

But he could not read it.

The state language of Andhra Pradesh where he was born and brought up is

Telugu,

which is linguistically quite distant from Hindi,

the official language of India.

Completely different.

He was quite talented not only in photography but also in languages.

However, Hindi is not one of them.

Unlike my classmate who could not speak Hindi at all,

he had somehow managed with this language

when we went out to the centre of the city.

(In the campus Hindi also seemed to have been considered a local language, but English was dominant.)

In the city,

I witnessed how the Delhi locals noticed that

he was not a Hindi speaker.

He was easily recognized as someone from the South.

He was frustrated and irritated.

“They say we do not speak Hindi fluently. But at least I can manage somehow.

How about them?

They do not even know a single word of any Southern languages at all,” he complained.

That was the reality back then.

2.

However,

it was North India itself that he had chosen to travel for photographs.

And it was those portraits that overwhelmed me.

I fell in love with his photographs at first sight.

I loved his talent.

He was loved by everybody

because of his nature – gentle, kind, generous and helpful.

He also showed affection and sympathy to the people of

the “backward classes,”

as defined by the constitution of India.

He showed me his camera with which he had taken those portraits.

His made in India camera seemed to me a toy.

I could not believe that those portraits had been taken with that “toy camera”.

When I met him,

he already owned a Japanese camera,

but he still kept his “toy camera” as his treasure.

The places he had traveled were mostly

hill areas

while his native place was near

the ocean.

Most portraits were of marginalized people such as

“scheduled tribes” – according to the constitution – or

Muslims, a religious minority. There were

Tibetan refugees as well as

Sikh victims, as repercussions after the assassination of Indira Gandhi in 1984.

India had not embarked on its economic take-off yet;

It was still a developing country and was known as

“a kind of” socialist economy.

It was before 1990, that is, before the transition

from socialism to capitalism.

On the other hand,

Japan was the sort of country which stood out in the world.

I saw the name of a Japanese business person, Yoshiaki Tsutsumi,

in an Indian newspaper reported as the world’s wealthiest person.

Japan had been admired in the capitalist world as

a front runner in economic development,

although we had been dishonorably called as

an “economic animal”

by a Pakistani former foreign minister in 1965.

Returning to Japan,

I made every possible effort to publish his photo collection.

Ironically,

this endeavor soon struck a fatal blow to our friendship.

When I came back to Japan,

he had already shifted to Madrid.

Our circumstances had been drastically changed by then.

However,

both of us did not realize

how it would affect our relations.

3.

In hindsight,

from the vantage point of the years gone by,

it is hard to believe how all of them

– publication, his photo exhibition and visit to Japan –

became possible during my chaotic personal situation in those days.

Everything was prepared and arranged

without him,

behind the scenes from his viewpoint.

Only the results reached him.

He was excited,

pleased.

Naturally.

Publication of photographs.

A solo exhibition, though small scaled, in Kyoto and Kobe.

Accommodation readied for his stay.

He should have been informed on

how many people were engaged and endeavored in all of them,

sometimes without being paid,

voluntarily,

just out of the spirit of goodwill,

or

just to support a budding Indian photographer

that sounded exotic to the Japanese.

I should have explained all the details to him,

but I didn’t.

Neither did I tell him

how miserable I was at that time.

I had just become a mother with a full time job,

living alone with a newly born baby.

Local newspaper and TV reporters came to my office to interview me,

being the first female university lecturer

who became a mother in that locality.

They were excited due to its news value for that small town,

because Japanese society as a whole was shocked by

the new record of the lowest birth rate since 1966.

(And now in 2022, the situation has become worst since then.)

My husband worked in a different city

so he showed up in our home only once a week

just to see our baby, that

made me more exhausted and

gave me more challenges in adjusting.

Needless to say,

the university staff were not accustomed to a female mother colleague.

(“Female” and “mother” seemed to them

very embarrassing adjective for a colleague.)

Everything was completely new and unusual to everybody.

I lost my balance.

I was in trouble when he arrived.

I hardly took care of him during his stay in Japan.

I had to ask my Japanese friend very privately

to look after him, instead of doing it myself.

Attendance,

transportation,

interpretation,

translation, and so on.

I handed over to my Japanese friend almost every responsibility that

I was supposed to take as a friend.

He left Japan in anger.

I collapsed, irrespective of his anger.

I literally fell down.

I had to take one-year sick leave and then got divorced.

Anyway, that is another story.

In retrospect, what I am feeling now is,

even if I had explained my difficult situation at that time,

he would not have understood why it was so.

He is an Indian.

Indian society was so advanced from the educated female viewpoint that

an educated middle class woman did not bear

such heavy burdens as I did.

Or, I must say

Japanese society was/is desperately underdeveloped at this point.

The dean of the Centre for South Asian Studies in JNU at that time was

a female professor who had children with her journalist husband.

At home, she kept a woman for household chores.

She was not an exception.

An elder sister of my classmate was a judge,

which was rarely found in Japan.

I remember being very impressed by a female judge.

After all,

my Indian friend and I belonged to each respective societies.

We were too immature to imagine another reality beyond the borders.

No less than a quarter century has passed since then.

In my desk’s drawer, I keep his photos.

Lots of photos are still there, lost with nowhere to go.

P.S.

I finally succeeded in contact with him on December 24, 2022.