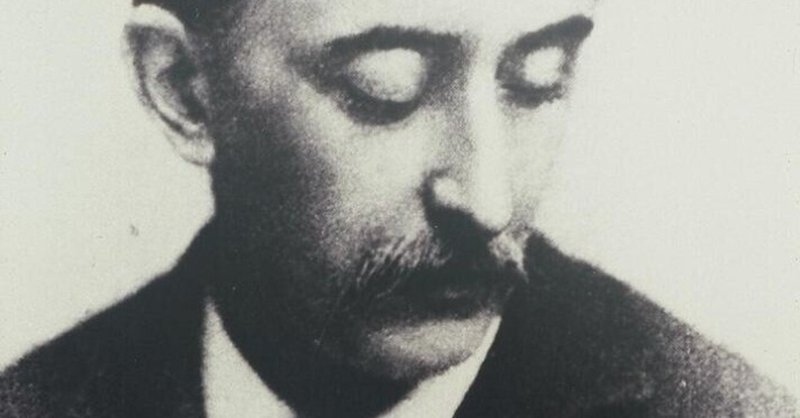

【読書】Kokoro: Hints and Echoes of Japanese Inner Life by Lafcadio Hearn心 日本の内面生活の暗示と影響 ラフカディオ・ハーン小泉八雲 岩波文庫

(とある冊子に寄せた原稿です。)

いつも、特集タイトルについてまず考えるのです。今回のお題は、またなんともむずかしい。

つらつらとテーマを頭の中でころがしていると、「争うこと」と「赦すこと」は対立するガイネンではないのでは…とか考え出すわけです。以前J・デリダの解説書か何かで、「赦しえないものを赦すこと」っていう章のタイトルがあったな…。「赦す」というのは「赦せない」と思うものがある時にはじめて出てくる言葉だ…。「赦せない」というのは、どういうことなのだろう…。それは、対象の問題ではなく、主体の問題ではないだろうか。つまり「争うこと」は対象と主体の間にあるのではなく、あくまで主体に内在する問題(トラブル)なのではないか…などなど、わけのわからない迷路に入り込んでゆくのであります。こりゃたいへんだ。

というわけで、なにか作品を材料にしよう。実はお題をいただいたころ、E・M・フォースターの『ハワーズ・エンド』を読んでいて、これで書けるかも、と思っていたのですが、読み終わってしばらくしたら、もう記憶があやふやになってしまい。嗚呼。そして最近、レイモンド・チャンドラーの『ロング・グッドバイ』を読んでいて、あっこれでも(かなりの無理筋だが)書けるかも、と思っていたのですが、これも読み終わったら記憶が飛ぶ雲の如く…。嗚呼。とにかく記憶力がありません。残念です。

そんな時に暇つぶしに見ていた電子辞書のテキストファイルで、以前に容れたラフカディオ・ハーンの『Kokoro: Hints And Echoes of Japanese Inner Life』のAT A RAILWAY STATION に遭遇したのでありました。「赦すこと」というお題に関わるように思うのでご紹介します。日本語訳は岩波文庫で出ています。

まず、ハーン小泉八雲の『心 日本の内面生活の暗示と影響』1896年 冒頭にはこんなことが書かれています。

(このように原書にも漢字が印刷されているようです。)

THE papers composing this volume treat of the inner rather than of the outer life of Japan,—for which reason they have been grouped under the title Kokoro (heart). Written with the above character, this word signifies also mind, in the emotional sense; spirit; courage; resolve; sentiment; affection; and inner meaning,—just as we say in English, "the heart of things."

KOBE September 15, 1895.

この一巻を構成している諸篇は、日本の外面生活よりも、むしろ、内面生活を扱っている。そういうわけで、これらの諸篇は、「心」という表題のもとに集められたわけである。「心」という字は、情緒的な意味では、信念という意味ももっている。つまり、精神、胆力、情操、愛情、それからわれわれが英語で「事物の真髄」というような、内奥の意味ももっている。

岩波文庫 平井呈一訳

この作品には、ハーンが日本で見たさまざまな情景と、そこにあらわれた日本人の「心」の様相が描かれます。その最初のおはなしが「AT A RAILWAY STATION 停車場で」です。原文はこちら。そんなに長くないので、どうぞ。

AT A RAILWAY STATION

Seventh day of the sixth Month;— twenty-sixth of Meiji.

Yesterday a telegram from Fukuoka announced that a desperate criminal captured there would be brought for trial to Kumamoto to-day, on the train due at noon. A Kumamoto policeman had gone to Fukuoka to take the prisoner in charge.

Four years ago a strong thief entered some house by night in the Street of the Wrestlers, terrified and bound the inmates, and carried away a number of valuable things. Tracked skillfully by the police, he was captured within twenty-four hours,—even before he could dispose of his plunder. But as he was being taken to the police station he burst his bonds, snatched the sword of his captor, killed him, and escaped. Nothing more was heard of him until last week.

Then a Kumamoto detective, happening to visit the Fukuoka prison, saw among the toilers a face that had been four years photographed upon his brain. "Who is that man?" he asked the guard. "A thief," was the reply,—"registered here as Kusabe." The detective walked up to the prisoner and said:—

"Kusabe is not your name. Nomura Teichi, you are needed in

Kumamoto for murder." The felon confessed all.

I went with a great throng of people to witness the arrival at the station. I expected to hear and see anger; I even feared possibilities of violence. The murdered officer had been much liked; his relatives would certainly be among the spectators; and a Kumamoto crowd is not very gentle. I also thought to find many police on duty. My anticipations were wrong.

The train halted in the usual scene of hurry and noise,—scurry and clatter of passengers wearing geta,—screaming of boys wanting to sell Japanese newspapers and Kumamoto lemonade. Outside the barrier we waited for nearly five minutes. Then, pushed through the wicket by a police-sergeant, the prisoner appeared,—a large wild-looking man, with head bowed down, and arms fastened behind his back. Prisoner and guard both halted in front of the wicket; and the people pressed forward to see—but in silence. Then the officer called out,—

"Sugihara San! Sugihara O-Kibi! is she present?"

A slight small woman standing near me, with a child on her back, answered, "Hai!" and advanced through the press. This was the widow of the murdered man; the child she carried was his son. At a wave of the officer's hand the crowd fell back, so as to leave a clear space about the prisoner and his escort. In that space the woman with the child stood facing the murderer. The hush was of death.

Not to the woman at all, but to the child only, did the officer then speak. He spoke low, but so clearly that I could catch every syllable:—

"Little one, this is the man who killed your father four years ago. You had not yet been born; you were in your mother's womb. That you have no father to love you now is the doing of this man. Look at him—[here the officer, putting a hand to the prisoner's chin, sternly forced him to lift his eyes]—look well at him, little boy! Do not be afraid. It is painful; but it is your duty. Look at him!"

Over the mother's shoulder the boy gazed with eyes widely open, as in fear; then he began to sob; then tears came; but steadily and obediently he still looked—looked—looked—straight into the cringing face.

The crowd seemed to have stopped breathing.

I saw the prisoner's features distort; I saw him suddenly dash himself down upon his knees despite his fetters, and beat his face into the dust, crying out the while in a passion of hoarse remorse that made one's heart shake:—

"Pardon! pardon! pardon me, little one! That I did—not for hate was it done, but in mad fear only, in my desire to escape. Very, very wicked have I been; great unspeakable wrong have I done you! But now for my sin I go to die. I wish to die; I am glad to die! Therefore, O little one, be pitiful!—forgive me!"

The child still cried silently. The officer raised the shaking criminal; the dumb crowd parted left and right to let them by. Then, quite suddenly, the whole multitude began to sob. And as the bronzed guardian passed, I saw what I had never seen before, —what few men ever see,—what I shall probably never see again, —the tears of a Japanese policeman.

The crowd ebbed, and left me musing on the strange morality of the spectacle. Here was justice unswerving yet compassionate,— forcing knowledge of a crime by the pathetic witness of its simplest result. Here was desperate remorse, praying only for pardon before death. And here was a populace—perhaps the most dangerous in the Empire when angered—comprehending all, touched by all, satisfied with the contrition and the shame, and filled, not with wrath, but only with the great sorrow of the sin,—through simple deep experience of the difficulties of life and the weaknesses of human nature.

But the most significant, because the most Oriental, fact of the episode was that the appeal to remorse had been made through the criminal's sense of fatherhood,—that potential love of children which is so large a part of the soul of every Japanese.

There is a story that the most famous of all Japanese robbers, Ishikawa Goemon, once by night entering a house to kill and steal, was charmed by the smile of a baby which reached out hands to him, and that he remained playing with the little creature until all chance of carrying out his purpose was lost.

It is not hard to believe this story. Every year the police records tell of compassion shown to children by professional criminals. Some months ago a terrible murder case was reported in the local papers,—the slaughter of a household by robbers. Seven persons had been literally hewn to pieces while asleep; but the police discovered a little boy quite unharmed, crying alone in a pool of blood; and they found evidence unmistakable that the men who slew must have taken great care not to hurt the child.

(概略)

熊本で捕らえられた強盗犯が、護送中に警官を刺し、行方が知れずにいた。ところが、熊本の探偵が、福岡の刑務所で、窃盗の懲役人の中に、その殺人犯野村貞一を発見した。そこで彼は殺人犯として熊本に送られることになった。正午着の汽車で熊本に来るという電報を受け取ったハーンは見物に出かける。

殺された巡査は人望のある男であった。見物に集まる熊本の人間はけっしておとなしいたちではない。ハーンは憤面怒罵の群衆を予想して出かけたが、それはもののみごとにはずれた。

待たされた見物人の前に、兇悪な人相のがらの大きな罪人が、首をうなだれ、両手を後ろ手にくくりあげられて出てきた。物をいうものはひとりもない。そのとき、警部が、大きな声でどなった。

「杉原さん! 杉原おきびさん! ここにきておられますか?」

子どもをおぶったやせぎすの女のひとが「はい!」と答えて前にすすみ出た。殺された巡査の未亡人である。彼女は殺人犯と向かい合って立ち、あたりは死のごとく闃(げき)として静まりかえっている。

やがて警部が、女のひとではなく子どもに向かって、言い聞かせるように語りだした。

「坊ちゃん、これがね、四年前に、あなたのお父さんを殺した男ですぞ。あなたは、あの時はまだ、生まれておいでなさんなかった。お母さんのお腹んなかにいなすったんだったね。今ね、坊ちゃん、あんたを可愛がって下さるお父さんがいなさらないのは、この男のしわざなのですぞ。よくごらんなさい、この男を。(と、ここで警部は、罪人のあごに手をかけ、おい、顔を上げろ、ときびしく命じた。)よおくごらんなさい、坊ちゃん。恐がることはちっともありませんぞ。おいやだろうが、こりゃあ、あなたの務めなんだからね。ようく見てやるんですぞ。」

子どもはつぶらな目をひらき犯人を見つめた。涙がこぼれたが、泣きながらもまともにじっと睨みつめた。見物人は息の根が止まったようであった。

罪人がふと顔をゆがめ、へたへたとくず折れたとおもうと、顔を泥にうずめるようにすりつけたまま、叫び出した。悔悛の情きわまった声であった。

「堪忍してくんなせえ。~坊ちゃん、あっしゃァ、なにも怨みつらみがあってやったんじゃねんでござんす。ただもう、逃げてえばっかりに、~あっしゃァ坊ちゃんに申訳のねえ、大それたことをしちめえました。ですが、こうやって今、うぬの犯した罪のかどで、これから死にに行くところでござんす。あっしゃァ死にてえんです。よろこんで死にます。だから、坊ちゃん…どうか可哀そうな野郎だとおぼしめしなすって、あっしのこたァ、勘弁してやっておくんなせえまし。お願えでござんす。…」

子どもはやはり黙って泣いていた。見物の群れが警部と罪人を通すために、道を分けたとき、いきなり群衆ぜんたいがきゅうにしくしくすすり泣きをはじめた。そしてハーンはかつて見たことのなかった日本の警官の涙を見たのである。

ハーンはこの場面から、次のようなことを見て取ります。

罪科の結果を見せて、罪科の何たるかを知らせる勘どこをはずさぬ、慈悲に富んだ正しい裁き。

死の直前にただひとすじに許しを願う捨て身の悔悟。

浮世のままならなさと人間の本性の弱さとは骨の髄まで知りぬいるために、一片の憤りもなく、ただ罪に対する大きな歎きだけをもつ大衆。

そしてどんな日本人でもその精神のうちに大部分を占めている、わが子にたいする潜在的な愛情に訴えて罪人の悔悛を促した点に、この挿話の意義深さがあると記しました。

ここに描かれた「許し/赦し」は、人が人に向けて投じた主体的な行為ではなく、また、西欧的な神による赦しでもありません。それは、日本的な大衆/世間のひとびとの、運命への諦念と歎きの共有によってあらわれた、ひとつの現象でした。ハーンの驚きと感動の眼は、このような、日本的な、(「個」に発するものではない)「現象としての心」を克明に描き出したのだと思います。

さて、このような日本的大衆の現象としての心はどうなったのでしょうか。SNSの普及が、先ほどの「赦しの現象」とは逆方向の、「赦さずの現象」を増幅させているようにも見えます。(ただ、この「現象」は、本源的にはひとつのものだと思います。よかれあしかれ、日本的なメンタリティには西欧的な「個」はセットされていないのかもしれません。) また、罪を犯した人のその後の様相は、ハーンの挿話の殺人犯とは異なる場合も多いようです。そんな中で目にするさまざまな事件。例えば先日行われた裁判についてこのような報道がありました。

旧通産省工業技術院の元院長の飯塚幸三被告は、昨年4月19日、東京都豊島区東池袋の都道で、横断歩道の通行人らを次々と乗用車ではね、自動車運転死傷処罰法違反(過失運転致死傷)の罪に問われている。この事故では、自転車で横断中の松永真菜さん(当時31)と娘の莉子ちゃん(当時3)が死亡し、通行人ら9人が重軽傷を負った。飯塚被告も胸の骨を折って入院した。

昨年4月、東京・池袋で起きた暴走事故で、89歳になる被告が「アクセルを踏み続けた記憶はない」と初公判で無罪を主張したことが、大きな波紋を呼んでいる。

初公判後の記者会見で拓也さんはこう話した。

「謝るのであれば、罪を認めてほしい。遺族の無念さと向き合っているとは思えない」「入廷する飯塚被告を見たとき、怒りやむなしさ、悲しさがこみ上げた」「(被告の無罪主張は)は、ただただ、残念だ」

初公判では拓也さんの事故直後の心境をつづった調書も読み上げられた。

「真菜の顔は傷だらけで、莉子の顔は『見ないほうがいい』と看護師に止められた」「莉子には『大好きだよ。お母さんの手を離さないでね』と、真菜には『莉子を天国に連れて行ってあげてね』と、繰り返し声をかけ続けた」

記者会見で事故直後の思いを質問されると、拓也さんは感情を抑えながらも「2人の遺体と手をつなぎ、夜を過ごしたことを思い出して、涙が止まらなかった」と振り返った。

ハーンの『心』の挿話と比べると、両者の相違が際立ちます。「歎きの共有」「惻隠の情」が、今後この場所に立ち上がることがあり得るのか。みなさんは、池袋の事例と「赦し」の問題をどのように考えるでしょうか…。

2021.7.17

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?