COVID-19 Japanese Schools as of May 2020 in the wake of the disaster: Stress and psychology in Japanese schools to be considered now (COVID-19災害を受けた2020年5月現在の日本の学校―今、考えたい日本の学校のストレスと心理―)

TAKAGI Ryou ,Shujitsu.University(高木亮、就実大学)

Introduction(はじめに)

This article was originally published in SYNAPSE 74 (pp.32-), a magazine for elementary and junior high schools and teacher training schools in Japan. It discusses the situation, challenges, and prospects for Japanese schools as of May 2020, about two months after the start of the COVID-10 disaster. This manuscript is the first in a series of articles, and we have already published other articles as follows. I will gradually upload them in the same format as this paper.

July 2008: "Stress and Crisis Management in Schools to Consider Now that the New Type of Corona is Emerging: Contributions that Schools Can Make in a Lifestyle Crisis," Synapse, 75, pp. 36-41.

September 2008: "Now that the New Corona is Here, How to Think about Learning and Costs - Investing in the School Community is Important for the Process of Improving Learning and Academic Achievement," Synapse, 76, pp.30-35.

November 2008: "Now that the New Corona is Here, I Want to Think about Deflationary Mindsets in Schools: Don't Forget to Reform Work Styles with the New Corona," Synapse, 76, pp. 30-35.

January 2009: "Educational Activities and Academic Achievement in the New Corona: The Difficulty of Using Data as Indicators for Productivity and Evidence," Synapse, 78, pp. 28-33.

In "The New Corona, School District and Social Psychology: Stress and Social Capital in Emotional Pornography and Cancellation Culture," SYNAPSE 79, pp. 36-41, April 2009.

This article is intended to be published in English with the permission of JIDAI. For this reason, revisions to the text at the time of publication have been limited to the minimum necessary for English culture.

If you would like to read the Japanese version, please request a back issue from JIDAI (http://jidaisha.co.jp/posts/post.html) or see the end of the text.

(本稿は日本の小学校と中学校、教員養成校向けの雑誌『SYNAPSE』(ジダイ社)74号(pp.32-)に「新型コロナの今、考えたい学校のストレスと心理」『シナプス』74,pp.32-33.掲載した原稿です。COVID-10災害の始まってから2か月程度の2020年5月時点での日本の学校の状況と課題・展望を議論しています。なお、本稿は連載の第一回で、以下のように既刊の原稿を発表済みです。順次、本稿と同様の書式でアップロードしていこうと思います

・20年7月:「新型コロナの今、考えたい学校のストレスと危機管理

-生活習慣病的危機における学校だからこそできる貢献―」『シナプス』

75,pp.36-41.

・20年9月:「新型コロナの今、考えたい学びと費用の在り方 ―学習・

学力向上過程には学校コミュニティへの投資も重要―」『シナプス』

76,pp.30-35.

・20年11月:「新型コロナの今、考えたい学校のデフレマインド ―新型

コロナで働き方改革を忘れてはいけない―」『シナプス』76,pp.30-

35.

・21年1月:「新型コロナの今、考えたい教育活動と学力 ―指標となる

データで生産性とエビデンスに付き合う難しさ―」『シナプス』

78,pp.28-33

・21年4月:「新型コロナの今、考えたい学校の学区と社会心理学

―ストレスと社会関係資本で考える感動ポルノとキャンセルカルチャー

―」『SYNAPSE』79,pp.36-41.

『Note』にはジダイ社の許可を取った上で、英文として発信することを目的に掲載しています。そのため、刊行時の本文の修正は英文化のための最低限度の調整にとどめています。

日本語版をお読みになりたい場合はジダイ社(http://jidaisha.co.jp/posts/post.html)にバックナンバーをご請求になるか、本文末をご覧ください。

Stress (threat) with a known reason and stress (anxiety) without a reason

As of February 1, COVID-19 (new coronavirus infection) became a designated infectious disease that requires special treatment such as isolation by order of the Japanese government. Since March, all elementary schools, junior high schools, and high schools in Japan have been temporarily closed at the request of the Japanese government. In Japan, there is no martial law, and the government cannot impose restrictions on the freedom of action of individual citizens. Social tensions are also increasing in Japan due to the fierce increase in deaths in the US and Europe.

In addition, there is increasing social confusion based on human psychology, such as economic problems caused by the destabilization of the international situation and the unprecedented cooling of consumption and production, as well as difficulties in obtaining some products. COVID-19 has become an issue of uncertainty in crisis management.

In this paper, we will consider the prospects and considerations for Japanese schools in the future, taking into account the psychological challenges in schools in COVID-19 and the disruptions associated with COVID-19.

First of all, I would like to point out the difference between COVID-19, which is a problem that can be dealt with by natural science, and the confusion associated with COVID-19, which requires a combination of natural science and social science. There are two types of problems that cannot be addressed by natural science alone: "Anshin" and "Fuan". Anxiety is a feeling of psychological discomfort without reason. Both are difficult to eliminate by explanation or natural scientific action. It is necessary to distinguish them from safety and threat (psychological discomfort with reasons), which are psychological states with reasons that can be dealt with.

In the past 10 years, Japanese medicine has established the concept of separating illness ("Yamai") as an individual's subjective story (narrative) and disability with natural scientific evidence (evidence), and valuing each of them. For diseases, injuries, and disabilities that can be confirmed by numbers and X-rays, the criteria are clear, and scientific interventions such as medication are effective and beneficial. On the other hand, as the Japanese proverb says, "sickness begins from the mind," stress, apathy, and wandering mind create subjective sickness, and scientific intervention is difficult (see Seiji Saito, "Narrative and Evidence in Medicine," for details). (See Seiji Saito, "Narrative and Evidence in Medicine," for more details.) Security and anxiety are subjective issues, while safety and threat are scientific issues.

In workplaces, schools, and local communities where people with diverse subjectivities gather, there are many situations where subjectivity and science are confused. This is a problem of the relationship (caseness) of sick individual people that cannot be dealt with by medicine. Since illness is in the realm of subjectivity, it is difficult for the individual to realize that his or her own psychology, emotions, and behavior are distorted (lack of illness awareness). The scientific existence of COVID-19 can be said to cause confusion associated with COCID-19 due to the combination of social and case problems such as anxiety. The confusion associated with COVID-19 can distort the way children, parents, and staff view the everyday world. Furthermore, it can have a contagious effect not only on the school, but also on relationships in the staff room and among parents, resulting in confusing special cases. In other words, it is difficult to predict what will happen with COVID-19 accompanying disruptions. In other words, it is difficult to predict what will happen with COVID-19. In other words, schools are a social infrastructure that can't fight COVID-19, but can effectively fight the chaos that accompanies COVID-19.

The relationship between crisis management and stress among teachers and staff in Japanese schools

Supporting not only children but also local residents from life-threatening disasters and the accompanying chaos is called crisis management (Kikikanri in Japanese, a concept that encompasses risk management and crisis intervention). As of April 2020, COVID-19 is already a disaster, and various accompanying disruptions have already been seen. As of April 2020, COVID-19 is already a disaster and various accompanying disruptions are already being seen.

Crisis management is primarily a natural science effort to ensure the safety of life. In general, when faced with a disaster in a school, the first thing to do is to follow compelling instructions. After the crisis of the disaster itself has passed, the second task is the recovery of daily life and efforts to ensure security. The third task is the effort to normalize stress and mental health, which is called crisis intervention (see "Psychological Support for Crisis" by the Japan Psychological Clinical Association for more details). Mental health normalization efforts have traditionally been defined in Japan as student guidance ("Seitosidou"), daily life guidance ("Seikatushidou"), and educational consultation ("Kyouikusoudann") as issues that deserve emphasis. However, there are two priorities in the ongoing disaster: crisis management and daily recovery.

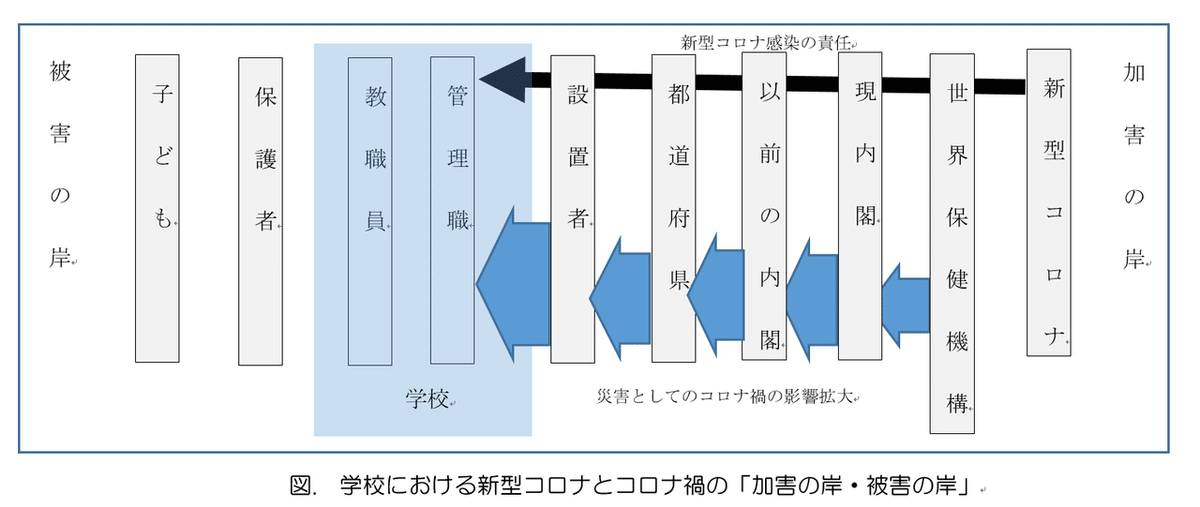

Tatsumi Tanaka proposed the "perpetrator's shore and victim's shore" as a model for considering the frameworks of the various positions of politics, government, schools, and children in Japan's disasters (Tatsumi Tanaka, "The Japanese Government's Earthquake Crisis Response is also Level 7," Bungeishunju, June 2011). In natural disasters, there is no original perpetrator, and everyone, people and organizations, is a victim. However, this model explains that the position with more authority and responsibility (meaning "blame" in Japanese) is relatively on the "side of the perpetrator. Furthermore, Mr. Tanaka's explanation does a good job of separating the disaster from the ensuing chaos. Based on this, the following diagram was created by the author in an attempt to organize the relationship between COVID-19 and COVID-19-related disruptions to children and parents of schools and teachers.

COVID-19 itself as an infectious disease is a natural scientific response, and various countermeasures can be proposed as time goes on. However, the confusion that accompanies COVID-19 is a matter of human subjectivity and human relations, which can be magnified by the passage of time. For example, the World Health Organization's responsibility for the outbreak has created an atmosphere of international relations problems, and the Japanese government has been criticized for its inadequate fiscal stimulus. However, it is in everyday local government and schools that the turmoil is growing in character and magnitude.

In addition, a Japanese mayor, who emphasized his position as a victim of the disaster and criticized the government, balked at the request to close schools temporarily in March. Mayors and local governments (the governing bodies of most elementary and junior high schools in Japan) are responsible for schools, and as the "perpetrators" of violence against weaker groups than schools, they have to take on the "blame game" (the etymological meaning of responsibility in Japanese). Also, from the perspective of Japanese society in general, school teachers and staff are expected to bear the stress of being on the "perpetrator's side" with authority and responsibility rather than on the "victim's side.

Again, the fundamental "perpetrator" is COVID-19, and we are all victims. As of May 2020, due to the Abe Cabinet's (resigning on September 16, 2020) request for temporary closure of schools, schools are largely exempted from taking the side of the perpetrators against children for the time being. However, once schools are reopened, it is necessary to reopen vibrant schools with COVID-19 risks, taking into account the worst-case scenario of "increased morbidity among children due to COVID-19 outbreaks in schools. Whether it is the continuation of temporary closure or the reopening of schools after May, schools need to be more or less prepared to take the side of the perpetrators against parents and children, no matter what. Whether schools continue to be closed temporarily or reopen after May, they must be prepared to take the side of the perpetrators, more or less, no matter what they do to parents and children.

By the way, Mr. Tanaka emphasizes that the excuse of "I am also a victim" by organizations and managers who failed to prevent the disaster to those who are in a weaker position than themselves will increase social confusion. I would like to think about the issue of stress among teachers and staff, paying respect to the stress of playing the role of the "perpetrator" while carrying the burden of the unprecedented daily life after the reopening of schools and the remote learning support during the temporary closure of schools.

Two points of job stress for teachers and staff

There are about 1,700 local governments in Japan (47 prefectures and about 1,700 municipalities). The total number of public and private schools in Japan is about 50,000. In addition, almost one million full-time teachers and staff work in Japanese schools alone, and the nature of their work ("duties") and the burdens and stresses they face are diverse and heavy to a degree unparalleled in the world. Although it is difficult to explain the stresses in a comprehensive manner, I would like to consider two types of job stresses that are likely to increase as a result of COVID-19, and three types of stresses caused by the social structure of the workplace.

The two types of job stress that will increase in the future for teachers and staff are the increase in job stress and the stress of adjusting to finding a new school after Corona.

In the event of an earthquake or tsunami, the Japanese public automatically assumes that the school is an emergency shelter. The school is also a "place that people can depend on in case of disaster. Because of this over-emphasis on service, Japanese schools have been highly influential in fulfilling the high expectations and responsibilities of both children and parents. As a result, Japanese teachers and staff tend to work long hours, often at the expense of their physical health and work-life balance. The Corona disaster is expected to push up the stress level of almost all Japanese people, and stress is expected to flow into schools as a place where people depend on ("Amaeru" in Japanese means "to devour sweetness"). For the time being, we can imagine that the same kind of stress that has been carried by schools and teachers will become quantitatively greater.

In addition, the conditions under which COVID-19 is apparently rampantly infectious are difficult to cope with only by devising educational methods, and may require changes in the curricula, school life, and school architecture of Japanese schools, which are characterized as "schools that learn by living. Bukatsudou, or extracurricular learning in sports and music, will have to change dramatically. Over the next few years, Japanese schools will have to adapt to the increasing number of COVID-19 cases, no matter how much they try to prevent them, through trial and error and the search for new school forms. The need to change the environment, as required by COVID-19, is a major source of stress for Japanese teachers and staff. The process of adaptation is significant for the future, as COVID-19 triggers the teachers and staff to change the school to adapt to the new era by themselves. However, it will add a heavy and long burden to the Japanese teaching staff, who have been suffering from overwork and stress to a degree rarely seen in the world.

The goal of "zeroing out" both infectious diseases and stress is not realistic. Rather, the pursuit of human happiness lies in the search for new ways to live with and adapt to them. In order to cope with illness and job stress, it is beneficial to have an "ESD way of thinking" that allows us to continue adapting without difficulty. The challenge will be how to combine this with the traditional trend in modern Japan of "people-friendly schools and teachers.

Staff Room Stress at Risk of Self-Destruction

The interpersonal (social) stress in the workplace, which is at risk of increasing, can be presented in some specific ways.

The first is the problem of faculty members having difficulty assigning work, feeling a sense of conviction (called "Kyoudousei" for collaboration), and feeling an atmosphere of warmth (called "Douryousei" for collegiality). This is collectively referred to as organizational climate stress, and its increase is imagined. The increase in organizational climate stress reduces work morale and increases the stress felt by teachers and staff when interacting with children and their parents. Managers in Japanese elementary and junior high schools seem to have a strong function as mood makers, strongly influencing the atmosphere in the staff room for better or worse. Therefore, the stress of the organizational climate can be called the "evaluation of teachers and staff by managers. For the time being, for reasons beyond the control of the school, it is necessary to go through the hardship of restoring the efficiency and emotion of the staff room again and again from "order -> opposite order -> chaos". The organizational climate of the school is a stress that needs special attention during the period of COVID-19 convergence.

The second is burnout, a mechanism in which excessive effort leads to pathological lethargy with a time lag. This is an occupational disease that is common in workplaces where people are systematically involved, especially in Japan. It can be prevented to a large extent by setting mechanical limits on workload and hours. In emergencies, people tend to feel the need to "just act" in order to relieve anxiety and threats, which in turn disrupts the organization and leads to burnout after self-destructive spinning. In an emergency situation of COVID-19 spread, the idea of preventing such a burnout may be especially necessary. Until there are more issues and conditions under the school's control, it may be effective to keep active efforts and discussions in the staff room under control.

The third is the stress of role conflicts that arise when multiple opinions, policies, and ideals are incompatible with each other. In Japan, children and their parents have always had a wide variety of requests to schools, and schools and teachers have been allowed a certain degree of freedom in how they respond. The good thing about Japanese schools is that they are ecologically rich, so that even if there are strictly mutual contradictions among the various requests, they can be vaguely integrated. In times of peace, this can be beneficial. However, in times of emergency, for example, there are so many different requests and complaints about the reopening of schools that even mutual conflicts are likely to arise. We need to temporarily drop the "negative list" concept and adopt a "positive list" concept during emergencies, that is, to set temporary limits on the roles and methods of education. In other words, it is important to temporarily limit the degree of freedom in the roles and methods of education.

The above suggestions for dealing with stress in the staff room are probably the opposite of what has been "important" in the management of Japanese schools up to now. It would be meaningful to have the sincerity to admit that there is no prospect of a new type of corona or a corona disaster at this time, the rational policy of concentrating on "what we can do in our limited schools," and the willingness to continue our efforts and show resilience no matter what happens.

The current school as a historical position

The heads of state have even called the Corona disaster a kind of "World War III. The First World War lasted four years, the Second World War five years on the European front, and three and a half years on the Pacific front, changing the social fabric of the nations of the world. COVID-19 will continue to demand new forms of economies, lifestyles, and schools over the next few years. It will be a long process of adaptation, like running a marathon while searching for a way to make COVID-19 a part of everyday life.

As of the year 2020, Japan is in the midst of the third educational reform in modern Japan, which began with the "Sanmi-Itsutai-No-Kaikaku" (meaning "trinity reform"), an administrative and fiscal reform in 2001 aimed at easing centralization. The first educational reform refers to the 30-year period of institutional design following the Meiji Restoration, and the second refers to the 30-year period from the end of World War II to the attainment of a per capita GDP equivalent to that of advanced Western countries and the increase in the percentage of students going on to higher education. If the third education reform, like the previous two education reforms, takes 30 years to take root, then it can be said that the third education reform will be a period of finishing the hard work of adaptation to find a new form of school required by COVID-19.

The third round of educational reforms, as evidenced by catchphrases such as "Ikiru-Tikara" ("Power to Live") and "Gakuryoku-No-3Youso" ("Three Elements of Academic Achievement"), has brought with it the idea of valuing more than "learning that can be easily measured by examinations. This was discussed at the beginning of this paper. In the discussion at the beginning of this paper, this is the idea of valuing both natural science (evidence-based) and narrative (narrative-based) academic skills. Narrative-based academic skills include motivation, attitude, competence, and non-cognitive abilities, which have received particular attention in recent years, and have been described as "the ability to learn in an environment that cannot be taught" (Paul Tough, "What Can We Do for Children?"). While COVID-19 created the subjective disaster of the Corona disaster, it could also be a catalyst for creating a new form of subjective school.

I hope that all the teachers and staff at schools will take care of their health and look for this conclusion, although it will take some time.

理由が分かるストレス(脅威)と理由のないストレス(不安)

COVID-19(新型コロナウイルス感染症)は2月1日付けで日本政府の命令により隔離などの特別な扱いを義務化した感染症(指定感染症)となった。3月から日本政府の要請で日本全国の小学校と中学校、高等学校の臨時休校(これらはほとんどが地方自治体か民間の法人が経営しているため、日本政府は「要請」以上の扱いができない)となった。また、4月7日からstate of emergency(緊急事態宣言)による国民の生活自粛も始まった(日本では戒厳令などがなく、国民個々人の行動の自由の制限などを政府が行うことができない)。欧米での猛烈な死者の増大もあり、社会的緊張感が日本でも増している。

さらに、国際情勢の不安定化や未曽有の消費・生産の冷え込みを背景とした経済問題、一部の商品入手困難など人の心理を背景とした社会的混乱も増しつつある。これらCOVID‑19に付随する社会的混乱(日本語で「コロナ禍」「Korona-Ka」)も今後、何が起こるか想像がつかない。COVID-19は危機管理の不確実性の問題となっている。

本稿ではCOVID‑19とCOVID-19に付随する混乱において学校での心理学的課題を踏まえつつ、今後の日本の学校の展望と留意点を考える。

まず、押さえたいのがCOVID‑19という自然科学で対応できる問題とCOVID-19付随の混乱のように自然科学と社会科学を合わせて考える必要のある問題の違いである。自然科学だけでは対応しきれない問題に「安心」(Anshin)と不安(Fuan)がある。安心とは漠然とした心理的平常性であり、不安とは理由のない心理的不快感である。いずれも説明や自然科学的な行動での解消は難しい。対処可能な理由のある心理状態である安全や脅威(理由のある心の不快感)とは区別して考える必要がある。

この10年で日本の医療の中で個人の主観的物語(ナラティブ)としての病(「Yamai」)と自然科学的根拠(エビデンス)のある障害を区分して,それぞれを大切にする発想が定着している。数字やレントゲンなどで確認可能な病気や怪我,障害各種は基準が明確で,投薬等の科学的介入が効果的で有益である。一方,日本のことわざで「病は気から」というが,ストレスや無気力,気の迷いは主観的な病を生み,科学的介入が難しい といえる(齋藤清二『医療におけるナラティブとエビデンス』が詳しい)。安心・不安は主観の課題であり、安全・脅威は科学の課題なのである。

多用な主観を持つ個々人が集まる職場や学校、地域社会には主観と科学が混乱しあう場面も多い。医療では対処できない病んだ個性的な人間の関係性(事例性)の問題である。病は主観の領域の存在なので自らの心理や感情,行動の前提が歪んでいることに本人自身が気づきにくい(病識の無さ)。さらに、集団や組織にすら伝染しねない特性(感応性)を持つため、拗らせれば事例性として組織・集団の混乱も生みかねない。COVID‑19という科学的存在は不安などの社会的・事例性の問題も重なることでCOCID-19付随の混乱が起きるといえる。COVID-19付随の混乱は子どもにも保護者にも教職員にも日常世界の見方を歪ませかねない。さらに、学校だけでなく職員室や保護者間の関係にも伝染するように影響し、混乱した特殊事例を生むことになりかねない。つまり、COVID-19付随の混乱とは何が起こるのか予測も困難である。見方を変えれば学校はCOVID‑19には対抗できないが、COVID-19の付随の混乱には有効に対抗できる社会基盤であるともいえる。

日本の学校の危機管理と教職員のストレスの関連性

生命の危機である災害と災害付随の混乱から子供だけでなく地域住民を支えることは危機管理(日本語で「Kikikanri」。リスク管理とクライシスマネジメント、クライシスインターベンションなどを包括した概念)として日本では「学校の仕事」として社会の中で定義されている。2020年4月の段階でCOVID‑19はすでに災害であるし付随の多様な混乱がすでに散見されている状況である。

危機管理は生命の安全確保を目指した自然科学的努力が第一の課題である。学校の中では一般的に災害に直面した場合、まずは強制力の強い指示に従うことが挙げられる。災害自体の危機が去った後に生活の日常への回復、安心確保の努力が第二の課題となる。第三の課題がストレス・メンタルヘルスの平常化の努力であり、これは危機介入といわれる(心理臨床学会『危機への心理支援学』が詳しい)。メンタルヘルス平常化の努力は日本では生徒指導(「Seitosidou」)や生活指導(「Seikatushidou」)、教育相談(「Kyouikusoudann」)として伝統的に強調に値する課題と定義されてきたが、災害現在進行時には危機管理と日常の回復という2つも優先する課題が存在することになる。

田中辰巳氏は日本の災害における政治や行政、学校、子どもといった様々な立場の枠組みを考えるモデルとして「加害の岸・被害の岸」を提唱した (田中辰巳「日本政府震災危機対応もレベル7」『文藝春秋』2011年6月号)。自然災害はもともとの加害者は存在せず人も組織も皆が被害者である。しかし、このモデルは権限・責任(日本語で「責められる任務」を意味する)をより強く持つ立場が相対的に“加害の側”に立つという説明がなされる。さらに、田中氏の説明は災害と付随する混乱を分けて説明する上で優れている。これを踏まえて学校と教職員の子どもや保護者に関わるCOVID‑19とCOVID-19付随の混乱の関係性の整理を試みて筆者が作成したのが次の図である。

感染症としてのCOVID‑19自体は自然科学的対応で、時間がたてば様々な対策が提示できる。しかし、COVID-19付随の混乱は人間の主観と人間関係の問題なので逆に時間がたつことで問題が拡大しかねない。例えば、世界保健機構の感染爆発における責任は国際関係の問題の雰囲気を呈しているし、日本政府の財政出動の不充分さが批判されている。ただ、より混乱の個性と大きさを増しているのは日常的な地方自治体や学校などの現場である。

さらに、ある日本の市長は自らが被害を受ける側としての立場を強調し政府批判の上で3月の臨時休校要請に難色を示したが、二転三転の方針転換により混乱を拡大してしまった。市長や地方自治体(日本のほとんどの小中学校の経営母体)は学校に対し責任があり、学校よりも弱い立場への「加害の側」として「責められる任務」(日本語での責任の語源的意味)を担わざるを得ないのである。また、日本社会全般からすれば学校の教職員は「被害の側」というよりは権限・責任を有する「加害の側」に立つストレスを担うことを求められている。

繰り返しになるが根源的な“加害者”はCOVID‑19で人は皆が被害者である。安倍内閣(2020年9月16日退陣)の学校臨時休校要請により、2020年5月現在、学校が子どもに対する加害の側に立つ場面は当面の間ほぼ免除されている。しかし、学校再開後は“学校でのCOVID-19流行による子どもの罹患増大”という最悪事態も考慮しながら、COVID‑19罹患リスクと付き合った活気のある学校を再開する必要がある。なぜなら活気のない学校は子どもの基礎学力低下や子どもの未来について不安のある状態を作り出すことで、COVID-19付随の混乱自体の問題となるからである。5月以降は臨時休校の継続にしろ、学校の再開にしろ、学校は保護者や子どもに対して、どうやっても、多かれ少なかれ、加害の側に立つ覚悟が必要となろう。

ところで、田中氏は災害を防ぎきれなかった組織や管理職が自分よりも弱い立場の者に「私も被害者です」という言い訳をすることが社会的混乱を拡大する点を強調している。今まで例のない学校再開後の日常や臨時休校継続の遠隔学習支援等の大変さを担いながら、宿命的な“加害の側”の役割を担うストレスに心から敬意を払いつつ、教職員のストレスの問題をこの後、考えていきたい。

教職員の仕事内容ストレスの2つのポイント

日本には1700ぐらいの地方自治体(都道府県が47、市町村が約1700)がある。公私立をあわせると約5万の学校がある。また、日本の学校にはフルタイムだけでほぼ100万人の教職員が働き、担う仕事内容(以下「職務」)と直面する負担・ストレスは世界で例をみないほど多様で重い。全体をまとめるようなストレスの説明は難しいがそれでも敢えて、COVID-19により付随的に増すといえる職務ストレスを2つ、職場の社会構造のストレスを3つにまとめて考えてみたい。

今後増える教職員の職務ストレスは今までの職務ストレスの増大とコロナ後の学校を探す適応のストレスの2つである。

日本の国民は皆が地震や津波の際に自動的に「学校が緊急避難所」であると考える。学校は国民にとっても“災害の際に依存できる場”である。このサービスの過剰なほどの特徴を背景に日本の学校は子どもからも親からも高い期待と責任を果たしてきたがゆえに大きな影響力を持ってきたといえる。それゆえに、日本の教職員は長時間労働を担いやすく、身体的不健康やワーク・ライフバランスを犠牲にすることも多い。コロナ禍はほぼすべての日本人のストレスを押し上げ、国民が依存する(「Amaeru」日本語で「甘さを貪る」と表現する)場としての学校にストレスが流れ込むことが予測される。当面、今までの学校や教職員が担ってきたものと同種のストレスが量的に大きくなると想像できる。

あわせて、どうもCOVID‑19が猛烈に感染する条件は教育方法の工夫だけでは対処が難しく、「生活の中で学ぶ学校」という特徴を持つ日本の学校の教育課程や学校生活、学校建築の変更も必要となりかねない点である。部活動(Bukatsudou)というスポーツや音楽の教育課程外の学習などは大きく形を変えることになるだろう。これから数年かけて日本の学校はどんなに予防しても増加するCOVID‑19感染事例を受け試行錯誤を積み上げ,新しい学校の形を模索し適応していくことになろう。適応(Tekiou。日本語で「適度に対応する」を意味する)とは環境の変化に合わせて自らを変えていくことである。COVID-19が要求する環境を変化させる必要性が日本の教職員に大きなストレスとなる。COVID‑19が引き金となり教職員が自分自身で新しい時代に適応した学校に変化させていくという適応の過程は未来に向けて大きな意義がある。が、もともと世界的にもまれなほどの過重な労働とストレスに苦しむ日本の教職員に重く長い負担を追加させることになるだろう。

感染症もストレスも「ゼロにする」という目標は現実的ではない。むしろ、これらと共存し新しい適応の形を探ることに人間の幸福追求の方向性なのであろう。病気や職務ストレスと付き合う上で“無理なく適応を続けるESD的発想”が有益であり、これにあわせた “国民に優しい学校・教職員像”という近代日本の伝統的な流れをいかにまとめていくかが課題であろう。

自滅のリスクを持つ職員室ストレス

増加の恐れのある職場の人間関係(社会的)ストレスはある程度具体的なものが提示できる。

一つ目は教職員の仕事の割り振りや納得感(コラボレーションのことで「Kyoudousei」と呼ぶ),温かさの雰囲気(同僚性「Douryousei」と呼ぶ)を感じにくくなる問題である。これを総称して組織風土ストレスというが、この増大が想像される。組織風土のストレスの増大は仕事の士気を削ぎ,子どもや保護者と関わる上で感じる教職員のストレスを割り増す。日本の小・中学校の管理職は職員室の雰囲気を良くも悪くも強く左右するムードメーカーの機能が強いようである。そのため組織風土のストレスは“教職員の管理職評価”といえる。当面の間,学校ではどうにもできない理由で“命令→反対の命令→大混乱”から何度も職員室の効率と感情を復元する苦労が必要となる。学校の組織風土はCOVID-19収束までの間で特に配慮が必要なストレスであるといえる。

二つ目はバーンアウトといわれる過剰な努力継続が時間差で病的な無気力に至るメカニズムである。これは特に日本では組織的に人と関わる職場で当たり前のように発生している職業病である。労働負荷・時間の機械的上限設定でかなり防止できるといえる。非常時に人は不安や脅威の解消を目的に,“とにかく行動したい”と善意で感じ、それゆえかえって組織を混乱させることで、自滅的空回り後の燃え尽きに陥りやすい。COVID-19の感染拡大という非常時にはこのような燃え尽き症候群の予防の発想が特に必要であろう。学校がコントロールできる課題や条件が増えるまでは職員室での積極的な取組や議論は抑制的であることが効果的とも考えられる。

三つ目は複数の意見や方針,あるべき姿がそれぞれ相容れないときに感じる役割葛藤のストレスである。もともと日本では子どもや保護者の学校への要望はとても多様で,学校や教職員の応じ方にも一定の自由度が許されてきた。多様な要望の間に厳密には相互矛盾があっても漠然とまとまることができるような生態学的豊かさが日本の学校の良さでもある。平時であれば,これは有益である。が,非常時の現在は例えば学校再開一つとっても要望や困り感の訴えが多様すぎて,相互対立すら生じる見通しである。今までの“ダメなことを提示する”(ネガティブリスト)発想を一時的に取り下げ,非常時の間は“可能な範囲を提示する”(ポジティブリスト)発想つまり教育の役割や方法に一時的な自由度制限を設けることが重要であろう。

以上の職員室ストレスの対策提案は今までの日本の学校経営が“大切にしてきたこと”の逆の内容ばかりあろう。現時点では新型コロナもコロナ禍も見通しがつかないことを認める誠意と、“限られている学校で出来ること”に集中する理性的方針、そして何が起きても努力継続と復元力を発揮するという意欲を持つことに意味があるといえよう。

歴史的位置づけとしての今の学校

コロナ禍を各国元首は「第三次世界大戦」のようなものであるとまで呼んだ。一次大戦は4年、二次大戦は欧州戦線で5年、太平洋戦線で3年半つづき世界の国々の社会的構造をも変えることとなった。COVID-19もそれに付随して変化する経済や生活スタイルそして学校の新しい形を数年かけて要求し続けるものといえよう。COVID-19が日常にとココムことになるまでには道を捜しつつのマラソンのような息の長い適応過程になると展望される。

2020年現在、日本では2001年の行財政改革である「Sanmi-Itsutai-No-Kaikaku」(中央集権化の緩和を目的とした「三位一体の改革」を意味する)のころから始まった近代日本第三の教育改革のただなかである。第一の教育改革は明治維新後の学制から30年間ぐらいの制度設計期を指し、第二の教育改革は第二次大戦終戦から欧米先進国同等の一人当たりのGDPの獲得と進学率上昇までの30年間を指す。第三の教育改革も過去二回の教育改革同様に30年間の定着期間を要するのだとしたら,COVID-19の要求する新しい学校の形を探す適応の苦労が第三の教育改革の仕上げの期間となるといえよう。

第三の教育改革は「生きる力」(「Ikiru-Tikara」)や「学力の三要素」(「Gakuryoku-No-3Youso」)などのキャッチフレーズはから分かるように、“試験で測りやすい学び”以外も大切にする発想を持ってきた。これは本稿冒頭の議論でいえば自然科学的(エビデンスベース)学力も物語的(ナラティブベース)学力も大切にする発想である。物語的学力とは学習意欲・態度やコンピテンス、非認知的能力という近年特に注目される課題で、“教えることができない、環境で学ぶ力”と指摘(ポール・タフ『私たちは子どもに何ができるか』)されている。この辺りに、遠隔授業では確保しきれない皆が物理的に集まる生活学校としての日本の学校教育の固有の意義があるように思われる。COVID‑19がコロナ禍という主観由来の災害を生む一方で、逆に主観由来の新しい学校の形を作るきっかけになりえる。

学校現場の教職員の皆様はどうか健康に留意して、少し時間がかかるが、この結論を探してもらいたい。

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?