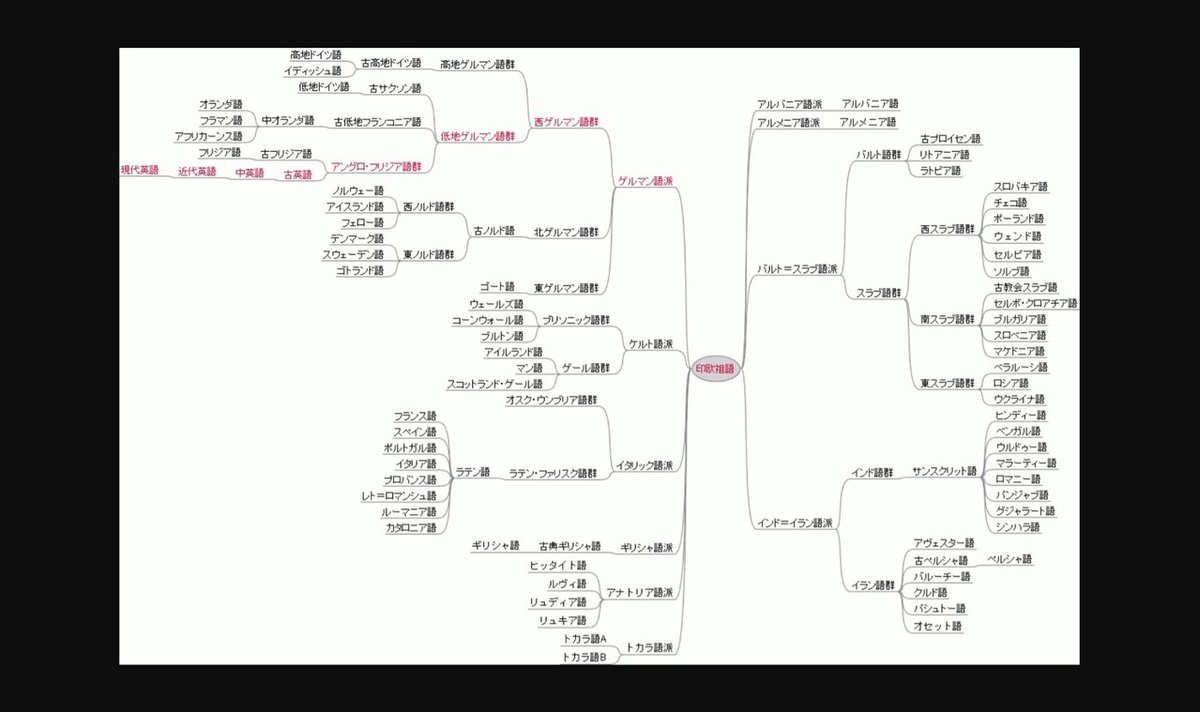

英語のルーツをご存じですか?英語、ドイツ語、フランス語、スペイン語、イタリア語、ポルトガル語、ラテン語、ギリシャ語、ロシア語、サンスクリット語、ヒンディー語、ペルシャ語、等々の言葉のルーツは実は同一言語なのです。

ルーツの根源として「印欧祖語」と記載されていますが、インド・ヨーロッパ祖語(英: Proto-Indo-European language、PIE)のことで、インド・ヨーロッパ語族(印欧語族)の諸言語に共通の祖先(祖語)として理論的に構築された仮説上の言語のことです。さて、この仮説上の祖先は実在したのか、また、実在したのであれば、地球上のどのあたりに生息していたのか?こんなことが、多くのDNA sequence data (発掘された古代人及び現代人)の比較から明らかになってきました。今回は、これに関する記事をご紹介させて頂きます。

このテーマに関し、最新のDNA dataをもとに、Origins of the Indo-European Language Familyを明らかにしたのが、David ReichによりMarch 2018に出版された下記の書籍に詳細が記されています。是非、ご一読を推奨いたします。世界観・人類観を拡げる意味で、非常に重要な書籍です。「人種」という概念の再考を否が応でも促されます。

翻訳版も出ています。

わたしのnoteにおいては、最新の科学・経済・社会等の問題に関して、英語の記事を引用し、その英文が読み易いように加工し、英語の勉強ツールと最新情報収集ツールとしてご利用頂くことをmain missionとさせて頂きます。勿論、私論を書かせて頂くこともしばしです。

The Exciting Origins of the Indo-European Language Family

By Neil Wright / Neil Wright is a senior transcriber at McGowan Transcriptions.

皆さんが苦労されてる英語の起源を知ろう!

How the Proto-Indo-European Language Spread

Over 2.6 billion of the world’s population speak a language belonging to the Indo-European language family. Millions of people learned the language over centuries of European expansionism. But this only tells half of the story. Even before colonialism, Indo-European languages spread far and wide. In fact, almost all of the people of Europe, the Near East (including Armenia and Iran), and northern India spoke languages that sounded similar.

Why and how’s that possible?

This is post (投稿メッセージ/póust) explores the origins of the Indo-European language family and answers how that came to be.

The Discovery of a Common Language Ancestor

European, Near East, and Indian languages all have similar origins. However, most people would agree that they sound very different from one another. Still, linguists have noticed similarities in their structures and have puzzled over them for centuries. In fact, they are so similar that most people [who study languages] believe they must have come from a common ancestral tongue.

One of the first people to notice these similarities was William Jones. He was a judge serving in British India during the late eighteenth century. Jones was an educated man and had also studied Greek and Latin in school.

On arriving in India he took the time to study and translate the language of the ancient religious texts of India, Sanskrit. As a result, he made the following observation:

“The Sanskrit language, whatever may be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious (言葉数が多い、内容の豊富な/kóupiəs) than the Latin, and more exquisitely (この上なく見事に、ものすごく、極めて素晴らしく、優美に) refined (上品な、洗練された) than either (Greek and Latin), yet bearing to both of them (Greek and Latin) a stronger affinity, [both (Greek and Latin) in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar], than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed that no philologer (言語学者) could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source,” – Thomas Burrow.

For the next 200 years, no more progress would be made outside of gathering more clues and comparative data on the linking of languages around the north-western Eurasian continent.

Then, in 1987, Colin Renfew published a compelling theory…

Did the Indo-European Language Family Originate from Anatolia (地図を見て頂くと、トルコ領域をANATOLIAとかいてあります)

In his book, “Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of the Indo-European Languages“, Renfew attempts to explain a single origin point for all Indo-European languages. He argues that it was the ancient people of Anatolia (Turkey) who spread their mother tongue over the continent approximately 8,000 years ago.

To some degree, this makes sense. The ancient Anatolians had developed complex farming methods that not only gave way to a massive population boom but drove the colonization of the new land using incentives like wealth. This fits with the anthropological argument that a language can only replace a pre-existing one if a large settler-immigration occurs there.

Renfrew’s argument won over most scholars. And it would hold sway (権勢を振るう、支配する) for about another two decades (~2007) until new evidence tilted the balance towards a new explanation.

Indo-European Wagon Migrations

In 2010, the anthropologist David Anthony published his book, called “The Horse, the Wheel, and Language“. He argued that almost all of today’s Indo-European languages have a shared vocabulary for wagons. He discovered similarities in all kinds of words relating specifically to wagons. Including ‘axle (車軸/ǽksəl)’, ‘harness (〔馬車馬の〕引き具、馬具、装着帯/hɑ́rnəs)’ and ‘wheel (車輪)’. And he believed that indicated that the first true Indo-European language must have originated in a civilization that used wagons. wagonを使用することにより、移動の範囲が広がり、また、戦いにおいても有利(戦車として利用)であった。ここで、重要なのは、馬を存分に利用していたことである。

The earliest archaeological evidence for wagon technology dates back only 6,000 years. That means the origin and spread of the Indo-European languages must have occurred much more recently than Renfrew suggests. In addition, ancient inscriptions (記されたもの、題辞、碑文、銘/inskrípʃən) recovered from modern-day Turkey reveal a language spoken that does not refer to wagon technology at all.

Language Migration and Assimilation (同化、同一化、吸収/əsìməléiʃən)

Anthony’s argument was already strong enough to lead linguists to prefer his views over Renfrew’s. However, evidence increased from the “wagon theory” in the second decade of the twenty-first century. This time from an unlikely source—the new and emerging field of ancient DNA studies.

DNA extracts from burial sites all over Europe and the Middle East reveal striking genetic similarities. This is strong evidence of large, recent waves of human migration into both regions. To the best knowledge available, the source of this expansionism didn’t come from Turkey. Instead, it came from the vast grasslands to the north of the Caspian and Black seas.

The grasslands of Kazakhstan, with the shores of the Caspian in the background, may represent the actual place where people developed the first Indo-European language.

Yamnaya’s Impact on Indo-European Languages

Given the archaeological evidence, the most obvious candidate for the mother tongue of all the Indo-European languages rests with the Yamnaya people. Early settlers left a trail of cultural artifacts in their wake (後に残す) as they migrated all over Europe. And the cultural legacies of the Yamnaya only serve to further strengthen that claim.

The word “Yamnaya” itself is a direct translation of a word meaning “Pit Grave Culture”. The Yamnaya buried their dead in single pit graves. (A practice that is still typical today.) It’s important to note that the Yamnaya also had wagon technology and came from the grasslands near the Caspian and Black seas.

Evidence of Yamnaya pottery is also widespread throughout much of Eurasia, specifically, “Corded Ware” pottery. The Corded Ware people are thought to be the descendants of the Yamnaya. Their name comes the “cord-like” pottery they created. And like the culture of single pit graves and wagon technology, this type of pottery is wide-spread. Overall, these signs point to large waves of settler migrations across the continent.

The Genome of the Indo-European Language Family

It does not seem immediately obvious on how ancient DNA studies can work towards finding the true origins of language. After all, examining DNA cannot tell us much about how people spoke or what language they used. But ancient DNA plays a vital role in helping linguists and scientists pinpoint which populations migrated where and when. And that gets us closer to finding the origins of the Indo-European languages.

Writing in 2018, the Harvard University geneticist David Reich put the most contemporary theory together in his book, “Who We Are And How We Got Here“. According to him, the most recent DNA evidence points to a single origin of the Indo-European languages south of the Caucuses, and probably in Iran or Armenia.

The debate continues…

There are plenty of unanswered questions and a lot of mystery around Indo-European language origins. But thanks to collaborations between the disciplines of linguistics, genetics, and archaeology, we may at long last (〔長期間の努力の末〕やっとのことで、ついに、やっと、ようやく)be closing in (近づく、迫ってくる、迫る) on them. And as our searches uncover more information, we get closer and closer every day to figuring out the true history of this dynamic, ancient language.