A Preliminary Examination of the Concept of "Object": From G. H. Mead to Gendlin in the 1980s

In the early 1980s, Gendlin began a preliminary examination of what an “object” is to living processes. By “preliminary,” I mean that at that time, Gendlin was examining only objects for animals that had acquired perception and behavior, following George Herbert Mead. In other words, he had not yet arrived at the consideration of an “object” in Chapter III of “A Process Model (APM)” (Gendlin, 2108) that also applies to unicellular organisms or plants.

In Chapter I of APM, Gendlin argues that “there is no single reality, only the reality of each species. It is in the sense of en#2 that each species has a different environment” (Gendlin, 2018, p. 5). Although the idea that each species has a different environment may have a genealogical origin in the “Umwelt (surroundings)” theory (Uexküll, 1934) of the European biologist Jacob von Uexküll (1864-1944), I will review the pragmatic genealogy here:

The environment of an animal that is locomotor differs from that of a sessile plant; that of a jelly fish differs from that of a trout, and the environment of any fish differs from that of a bird. So ... the difference is not just that a fish lives in the water and a bird in the air, but that the characteristic functions of these animals are what they are because of the special way in which water and air enter into their respective activities. (Dewey, 1938, pp. 25-6)

The [life] form which has no distant experience, such as an amoeba, or which has such distant experience involved only functionally, has not the sort of environment that other forms have. I want to bring this out to emphasize the fact that the environment is in a very real sense determined by the character of the form. (Mead, 1934, p. 247)

Mead argues that for each animal species, what it selects as an object from its environment differs: “The selection of the characters which go to make up food is a function of living individuals” (Mead, 1922, p. 158):

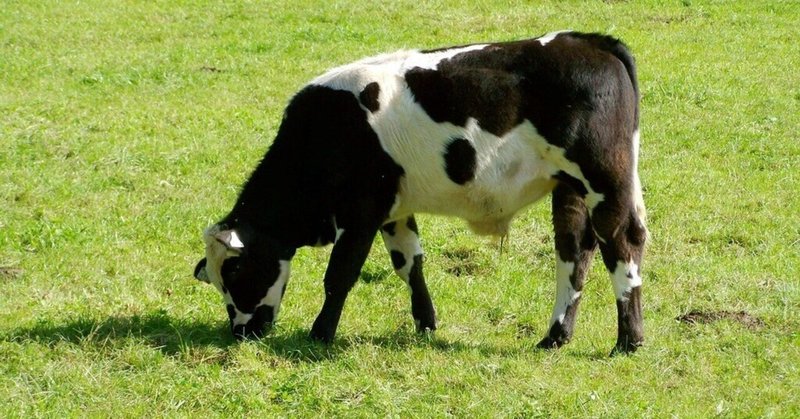

If an animal that can digest grass, such as an ox, comes into the world, then grass becomes food. That object did not exist before, that is, grass as food. The advent of the ox brings in a new object. In that sense, organisms are responsible for the appearance of whole sets of objects that did not exist before. (Mead, 1934, p. 129)

In the ’80s, Gendlin followed Mead’s ideas, arguing as follows. In other words, he considered that grass becomes food only when there is a digestive process:

Each species lives in its own mesh of objects which cannot be perceived by other species in the same way. For example, the complexity of the body's implying makes a food-object with the environment's cooperation. That object is not just there that way independently in the environment. (Gendlin et al., 1984, p. 260)

... eating isn’t just a reaction to food. Rather, food becomes an object only with the organism’s digestive process.... (Gendlin, 1984, p. 99)

It should be noted, however, that the “object” from Mead to Gendlin in the early 1980s is only an object for animals that have acquired perception and behavior. In other words, if the concept of an object here is to find its counterpart in APM, it is, in my opinion, the idea of an object in Chapter VI-B “The Development of Behavior Space”, and not the concept of an object in Chapter III “An Object”.

The part of the implied environment which might or might not occur is called an “object.” (Gendlin, 1984, p. 100)

Our III object could only be absent, but the VI object can be present, and it can also be absent. ... A behavior space in which many objects have fallen out is an advanced stage found only in higher animals. Behavior space does not first consist of objects. (Gendlin, 2018, p. 104)

Mead does not yet have the idea that “When the object returns, the stopped process resumes and moves on. Then the object is no longer implied” (Gendlin, 2018, p. 17; cf. Okamura, 2022), which corresponds to Chapter III in the later APM.

However, in the ’80s, Gendlin began to discuss the idea of the “stopped process,” albeit still in an inadequate form. He argued that “If the animal is hungry and there is no food, feeding cannot happen even though it is the body’s implied next event” (Gendlin et al., 1984, p. 260) and that “The implied action, for instance, eating, might not happen because there is no food. An implied action can not happen if the people and things it involves are missing” (Gendlin, 1984, p. 99). These ideas were gradually refined and later culminated in the following concept in Chapter III of APM: “As far as we defined it, there can be an object for the body only while the object is missing, and the process with it does not happen” (Gendlin, 2018, p. 16). I believe this finally leads to the presentation of a more fundamental concept of “object” that applies not only to animals but also to unicellular organisms and plants.

References

Dewey, J. (1938). Logic: the theory of inquiry. Henry Holt.

Gendlin, E.T. (1984). The client’s client: the edge of awareness. In R.L. Levant & J.M. Shlien (Eds.), Client-centered therapy and the person-centered approach: new directions in theory, research, and practice, pp. 76-107. Praeger.

Gendlin, E. T. (2018). A process model. Northwestern University Press.

Gendlin, E.T., Grindler, D. & McGuire, M. (1984). Imagery, body, and space in focusing. In A.A. Sheikh (Ed.), Imagination and healing, pp. 259-286. Baywood.

Mead, G.H. (1922). A behavioristic account of the significant symbol. Journal of Philosophy, 19, 157-63.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society: from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. (edited by C.W. Morris). University of Chicago Press.

Okamura, S. (2022). The body that forefeels future: from perspective on therapeutic subculture [in Japanese]. Bulletin of the Institute of Oriental and Occidental Studies, Kansai University, 55, 147-185.

Uexküll, J.v. (1934). Streifzüge durch die Umwelten von Tieren und Menschen. Julius Springer.

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?