Conversations with Things: Prefigurative Design for a Post-anthropocentric and Post-capitalist Future

モノとの対話:ポスト人間中心主義的でポスト資本主義的な未来のための予示的デザイン

スイス建築博物館で2022年に開催された "MAKE DO WITH NOW: NEW DIRECTIONS IN JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE" 展の図録に寄稿した文章です。(個人的にWebに掲載するのは問題ないということでしたので許可を得て公開します。)下記、展示と図録のリンクです。

後日、日本語版も作ろうと思っていますが、とりあえず日本語の要約を書きます。

これまでのデザインや建築の多くはヒエラルキーのある社会を前提としていた。本稿は将来のヒエラルキーのない社会を理想とした上で、それにふさわしいデザインや建築のありかたを考察する。そのためにデザインとは何かについての根本的な見直しを行う。またそのような未来のあり方を小規模でも現在において示す「予示的デザイン」(prefigurative design)として、筆者の関わった実践を紹介している。

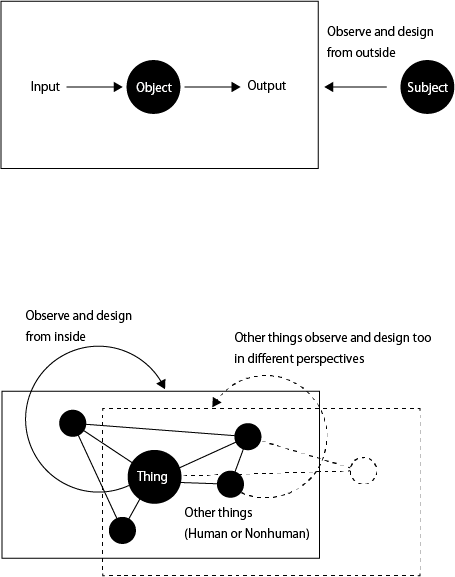

最初に、従来の一般的なデザインの考え方と、それにたいするオルタナティブを示す。一般的なデザインの考え方とは「対象のコントロール」である。対象は法則的にふるまう受動的な存在である。デザインはこれを外からコントロールする。それはまた、人間の目的のための手段として対象を合理化する問題解決である。オルタナティブとして本稿で提示する見方は、作ることやデザインすることは「モノとの対話」だと考える。人も非―人間(non-human)も何らかの能動性を持ったモノ(thing)だとみなす。モノたちを外から包括的に把握しコントロールする特権的な視点は存在しない。モノたちはそれぞれが固有で部分的な仕方で自分たちを再帰的に観察し、対話的にはたらかけており、それを通して相互の形が形成される。

従来の考え方の基盤にあるのは、近代科学を特徴づける機械論的な世界観である。後者の基盤となるものとして、パースの物活論的な宇宙論がある。(また、本稿では触れていないが他にもアクター・ネットワーク理論、セカンドオーダー・サイバネティクスなどがオルタナティブな見方の参考になる。これらの理論については、Designシンポジウム2019で発表した「対話を通した探究としての設計-パースの記号論とセカンドオーダー・サイバネティクスによる理論化」において論じている。)

従来の考え方は一般的に、人間にとって都合のよいように物事をデザインするという人間中心主義である。他方でオルタナティブな見方は非―人間にとっての物事を考慮するという意味で、ポスト人間中心主義的である。この観点から筆者が関わった二つのプロジェクトを紹介している。「スクラップ装飾社」は、廃材でデザインと制作を行うコレクティブである。モノに人間が形を押し当てるのではなく、モノとの対話を通してモノの側から形が生み出されることを促すための設計図として「やわらかい」設計図を開発した。「大見新村プロジェクト」は京都市の無住化集落の再生の活動である。ここで新しく伝統芸能を作ろうとしている。集落に存在する非―人間(杉、鹿、川など)演じて会議や踊りをする。これは非―人間との協働による集落のデザインを意図している。

現代社会において「モノとの対話」が困難で「対象のコントロール」の態度が支配的である。その要因として資本主義社会がある。そこでポスト資本主義的なデザインという観点が必要になる。この観点で筆者が関わったプロジェクトの「本町エスコーラ」を紹介している。これは、京都市において隣接する数軒の空き家を、共有空間のある住居・アトリエとして改修し運営を行うものである。ポスト資本主義社会のためには、市場に全面的に依存せずとも生活できるための条件としての「コモンズ」の創出が鍵となる。コモンズ創出のための方法として、これまで市場から購入していた商品やサービスを、コミュニティの内部で生産するように切り替えるという意味での「コミュニティによる輸入置換」がある。「本町エスコーラ」については、共著「お金のために働く必要がなくなったら、何をしますか?」第6章において論じている。

Architecture Without Hierarchical Control

Historically, architecture has been used as a way to control people and things. It has almost always relied on social and ecological exploitation: architectural structures cannot be built without laborers who are coerced to work under oppressive power relations or economic inequality, while building materials cannot be extracted without causing ecological damage. Against this, I want to prefigure an architecture without hierarchical control, which can be designed, built, and used without social and ecological exploitation. This raises certain problems because our current architectural methods and technologies presuppose exploitative practices. But it is not simply about technology. It also requires a reconception of the very notions of making and designing, along with their underlying metaphysics.

The following are examples of widely accepted traditional assumptions about making and designing as control:

The objective of making and designing is to control things.

Making things is to force matter to take particular forms.

Designing is to devise the forms before making things.

Design is problem-solving and the forms that it produces should be justified as solutions.

The result of design benefits humans, not non-humans.

Non-human things are resources to be exploited. They have value only as a means to an end, not simply as things that exist.

Making and designing are services that cater to the users of the end product. Therefore, these activities do not need to be enjoyable. On the other hand, in most cases, the experience of using the product should be enjoyable.

I believe these assumptions and their underlying metaphysics are too narrow, if not completely wrong. And their limited scope is partly responsible for causing today’s socio-ecological crisis.

Instead, I want to propose alternative notions and ways of making and designing, like the ones listed below:

The acts of making and designing should be conversations with things through which things develop their forms.

Things should not just be passive resources, but more or less living, autonomous entities.

Design should be of value for humans, non-humans, and non-living things. All of these have intrinsic value.

Design should not be reduced to mere problem-solving. Design should add a wide range of meaning and value to things from multiple perspectives.

The process of design and production should be just as enjoyable as the experience of using the designed product.

Designing must not be separated from making and using. A person can be a maker, designer, and user all at once. Even if they are not all three, there should be no power relations between designers, makers, and users. The relationship between these identities should be one of conversations, not of commands. If you are not adept at designing or making, someone else can do it for you. This would be an act of care, not of service. The process should not involve coercive toil at any point. Workers can work hard if they wish to, but it should not be a condition for survival.

We know that people should be treated as ends in themselves, not just as means to achieve an end. This also applies to non-humans – whether living or not – which should be recognized for their intrinsic value. Things are not passive materials to be molded into man-made forms. To make and design is to converse with things. Things want to become something. They do not speak the language of humans, but they respond to human action. They may deviate from our expectations. When they do, we hear their message, and must reply with another action.

Underlying Metaphysics

The top diagram shows the dualistic and mechanistic metaphysics underlying traditional notions about making and designing as control. The object is situated within a linear relationship and the subject observes and designs the object from outside the frame. The bottom diagram shows an alternative interaction. For the purpose of this exercise, let us consider both humans and non-humans as “things,” defined as actors with varying degrees of autonomy. Autonomy is not inherent to individual things but is rather achieved through interaction with others. Things observe and design their networks inside the frame from their particular perspectives. Some things may observe other things in the context of problem-solving and means-purpose relations, but nothing observes everything and no observation is complete. Things only identify what is missing and are able to fill in and renew their perspectives when they engage in “conversations” with others. In the bottom diagram, the perspective of these other things is suggested through the dotted lines. The conversation is essentially an improvisation, because it is a process through which participants find something new and respond with new actions.

Hylozoic Design for a Post-anthropocentric Future

In my own work, I aim to embody the alternative model of designing and making, and realize, even on a small-scale, architecture without hierarchical control or social and ecological exploitation. It is a prefiguration of architecture that is appropriate for a post-capitalistic and post-anthropocentric future.

Traditional metaphysics is anthropocentric, while the alternative metaphysics illustrated above is post-anthropocentric. The latter is also hylozoic. Hylozoism sees life in all material objects, as exemplified in the cosmology of the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce. Peirce’s idea of “inquiry” is also relevant here. He defines inquiry as an evolution of habits, and he postulates that our thoughts, actions, and perceptions are mediated by our habits. He sees not only humans but also the entire universe as habits evolving through inquiry.

Designing and making are forms of inquiry. We express our ideas and receive (sometimes surprising) feedback from others. These reactions prompt us to generate new ideas. The coexistence of different perspectives allows us to inquire because only another with a perspective that differs from our own can illuminate what is lacking.

Hylozoic design is conversing with things rather than controlling things. Living in a modern society based on a mechanistic worldview, we have lost the ability to hear what things “say.” We have to invent or reinvent methods to talk with things.

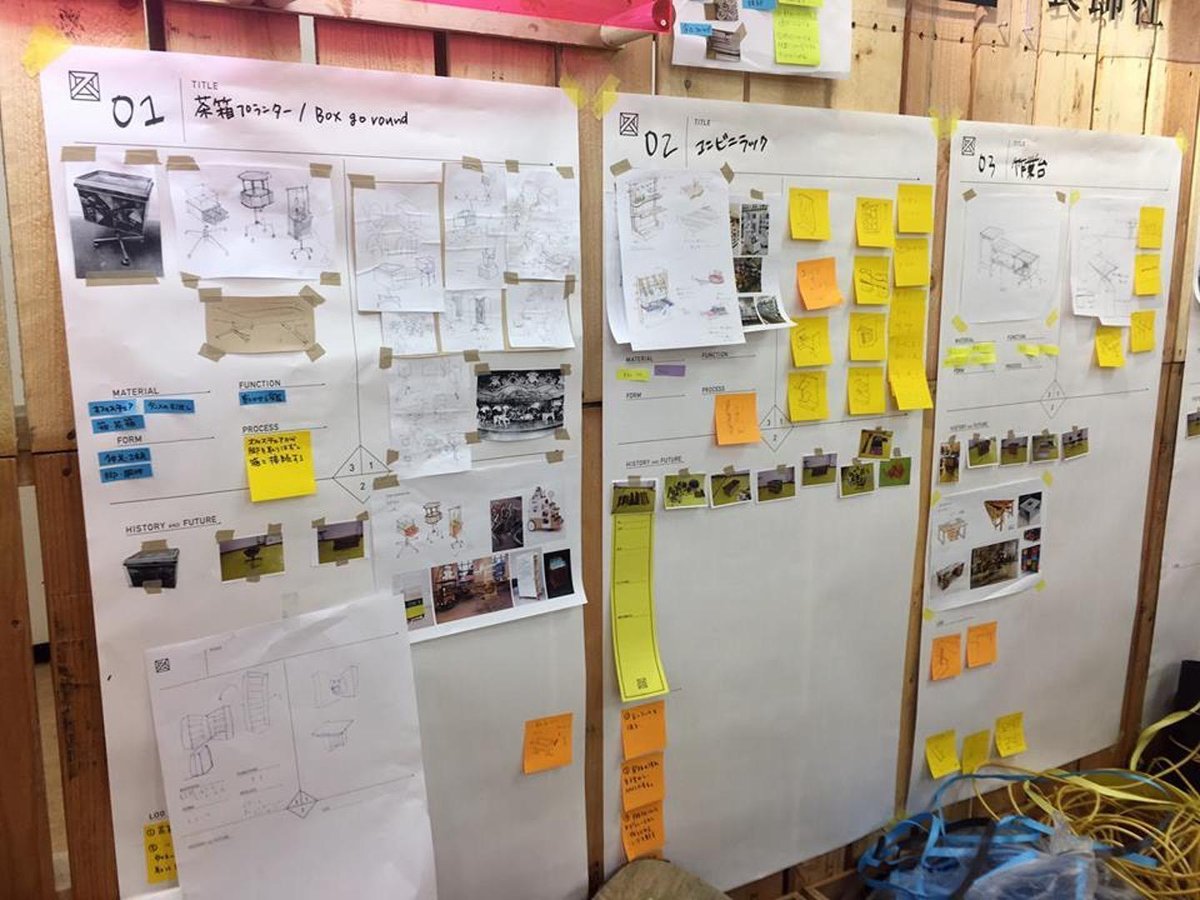

Scrap Sōshoku-Sha is a collective that collects waste materials from demolished or renovated houses, shops, and other structures and turns them into various objects for use. The materials inspire their design, rather than the design dictating which materials to source.

As part of my work with Scrap Sōshoku-Sha, I developed a so-called “soft” design drawing as a tool for hylozoic making. The traditional design drawing is unambiguous: makers make things exactly as shown in the drawing. The soft drawing is an ambiguous representation that allows for interpretation and prompts makers to have an improvisational conversation with the materials. It consists of three parts. The first part encompasses the realm of the imaginary, the mysterious, or the merely possible. The second part charts the trajectories of the particular materials used (from where they come and where they go). The third part describes form in an analogous way to traditional design plans. The drawing is intended to be filled in during the course of making.

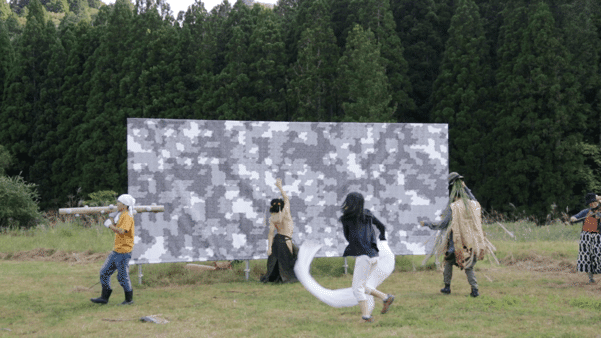

Oomi-Shinson is a project to revitalize a village in Kyoto called Oomi, which was abandoned in the 1970s due to the decline of the local charcoal industry, among other reasons. The project was started in 2012 after a descendant of one of the former residents started a farm in the region and moved back to the village. Since then, project members have worked to bring people to the area and envision how the village can thrive in the future. In order to re-establish a village culture, the members organize a “New Matsuri” (New Festival) once a year. In this event, attendees take part in discussions and dance, performing as human and non-human inhabitants of the village, such as the trees, rivers, or animals. This is intended to be an attempt to design a village with non-humans: though the direct involvement of non-humans is limited, having humans take on the roles of other species changes their perception of their non-human neighbors, letting them think about and interact with the village from a different perspective. New Matsuri includes physical performances because the non-verbal experience of playing others seems to facilitate this change in perspective.

Designing the Commons for a Post-capitalist Future

Having a conversation with things is not always easy in today’s manufacturing industry. If you are an architect who enters into a contract with an ordinary client, you are obligated to have the builder construct the building exactly as designed within a particular deadline. To meet the client’s demands, the builders employ standardized materials and methods to ensure that the process is timely and predictable.

Today, some architects participate in the construction of their buildings, sometimes together with the clients, or build a non-hierarchical team of developers, builders, and users. These attempts to blur the boundaries between design, construction, and use can make the process more improvisational and enjoyable – more of a conversation with things. But it is rare to find people who consistently incorporate such practices in their design and building process. In a capitalist society, we have to be competitive. And to be competitive, we have to be productive and efficient. It benefits us to build hierarchical organizations and systematize our work because it maximizes our efficiency.

The economist Karl Polanyi distinguishes three patterns of the economy: reciprocity, redistribution, and exchange. Reciprocity is mutual help, which is typical in popular sectors or communities: if you want a house, your friends can help build it, and you in turn help them out some other day. Redistribution is collection and distribution, usually done by the public sector or government: the government collects taxes and spends it to provide public housing. Exchange is done in the private sector or the market and usually mediated by money: you pay money to a constructor to buy your house. This is of course an ideal distinction; any economic process in reality can have all of those characteristics at the same time.

In a capitalist society, the realm of exchange grows, turning the commons into commodities. Commons are the non-market or non-monetary conditions to make a living. Natural commons like water and land, and social commons like knowledge, are free, but under capitalism they are exploited, privatized, and merchandised.

There are admittedly some merits to market exchange and capitalism. It encourages innovation and frees people from being socially bound to tightly knit communities and their norms. But in today’s world, capitalism has become counterproductive as indicated by the current ecological crisis. “More capitalism” does not correlate to increased freedom or innovation. Having access to the commons is the necessary condition for all of us to make inquiries. Some inquiries may be profitable in the market, but not all inquiries should be driven by monetary gain. The commons allows us to do things that do not make money.

One way to regenerate the commons is through a process I call “import replacement by communities.” Import replacement – as articulated by the urbanist Jane Jacobs – typically refers to an urban free-market economic process by which imports into a city are replaced by production from within it. Import replacement by communities posits an analogous process whereby a community substitutes exchange-based relationships with reciprocal relationships, thereby restoring the commons. It produces a higher diversity of activities in the community, which is crucial for the community’s autonomy. Do-it-yourself (DIY) practices can encourage import replacement in communities by developing skills, tools, and networks as a form of commons.

Honmachi Escola is a project that aims to renovate, partly in a DIY manner, a group of vacant properties in Kyoto into a complex of residences, workplaces, and shared spaces. This site/project is managed without hierarchical structures (at least in principle) by the users of the space, who also hold seasonal events and workshops. For me, the project is an experiment in creating a network of people and things that makes it possible to live without being totally dependent on money, replacing market transaction with non-market circulation of things, cares, and skills.

Seven years after the start of this project, one can say it has succeeded in fostering a network that works as a commons. The gardens are now cultivated by some members of the community, and the produce is shared among the group. Some members, including myself, started to learn blacksmithing, and while the blacksmith workshop has closed in the meantime, I now have the skills to make a knife. When some other members met and got married, I started making my own clothing and tailored a dress for their wedding party. I still make clothing for myself and others, and rarely buy clothing nowadays.

There was much to learn in that time. Managing shared space autonomously is not an easy task. There was a lot of conflict and some members withdrew from the project. Everyone has a different perspective, and I believe that is what makes it possible for us to make inquiries. But sometimes it can also cause anxiety. Because we rely on a discussion-based decision-making process instead of a top-down approach, many hours of talking are needed to arrive at each decision. This can be bothersome and tedious at times. The capitalist market is a way of outsourcing these anxieties and tedium. In order to regenerate the commons, however, we need to learn to deal with them.

The alternative model of making and designing as well as of their underlying metaphysics proposed above aims to create an architecture without hierarchical control or social and ecological exploitation. It has the potential to open up aesthetic possibilities, freeing architecture from the rigidity of mechanistic and monological frameworks. It may be an impossible ideal. But I also believe it is a legitimate ethical requirement for a post-anthropocentric, post-capitalist future.

Jun Yamaguchi is a researcher, designer/maker, and artist currently focusing on the prefiguration of post-anthropocentric and post-capitalist design. He holds a master’s degree and PhD from Kyoto University. His doctoral thesis explored architectural design process as a “conversation,” relying on the philosophy of Charles Sanders Peirce. He works as a part-time lecturer teaching Design Semiotics at Musashino Art University and Science Studies at Tokyo City University. He is co-author of Okane no tame ni hataraku hitsuyō ga nakunattara, nani wo shimasuka? [What would you do if you did not need to work for money anymore?] (Kōbunsha, 2018), a book on universal basic income. He designs and makes clothing and shoes, among other things. He is currently working on an art project for a dance with non-humans.

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?