Almost Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Hungarian Animated Film, And Weren't Afraid To Ask~Interview with Varga Zoltán (Part 2)

2010's ended several months ago. So I want to ask, what is the most essential Hungarian animation in 2010's in your opinion? For example, Milorad Krstić's "Ruben Brandt, a gyűjtő", Tóth Luca's "Superbia" and Jankovics Marcell's "Az ember tragédiája" etc. But how is your opinion?

I think many people would agree easily if I claimed that the 2010s meant a rather exciting decade of Hungarian animation, or at least it was more enthralling than the 2000s. Now almost ten years have passed since 2011, and in retrospective we could say that it was a symbolic year considering the following. That was the year when Marcell Jankovics’s Az ember tragédiája / The Tragedy of Man was finally finished and released (after he and his collaborators had been working on it for more than 20 years!), and also at the end of 2011 Hungarian Folk Tales was finished with the 100th episode. Maybe this coincidence is somehow the symbolic closure of a larger period, or a kind of a watershed, and we know what follows after this. Fortunately, those who made Az ember tragédiája and Hungarian Folk Tales, remained active in animated film making, even Marcell Jankovics, who formerly stated that Az ember tragédiája would be his last animated film. By the end of the 2010s he was engaged in a new adaptation: Jankovics and his crew are making the animated film version of János Arany’s Toldi, one of the greatest narrative poems of Hungarian literature, written in the 19th century. It will be a series produced by Kecskemétfilm, but it is intended to present it in a full-length version as well. This project definitely seems to be one of the most exciting works that are currently in progress in Hungary.

Returning to what happened in the 2010s, right after something had finished symbolically in 2011, something new began. Maybe we could say that the “newest new wave” of Hungarian animated film appeared when the students of MOME Anim (the animation faculty of Moholy-Nagy Művészeti Egyetem / Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design) presented their exam films and later their first individual short films. The educational programme of MOME Anim was developed by József Fülöp, so the flow of the successful films of his students can be considered as his merit as well; he also helped and helps with the making of these films as a producer. It is also worth mentioning that several exam films made at MOME Anim gained wide recognition earlier as well, but the 2010s definitely became the period of world success for MOME Anim’s short animations. The first piece of this stream was Nyuszi és Őz / Rabbit and Deer directed by Péter Vácz in 2013, which film was shown at more than 120 film festivals around the world. Since then dozens of well-crafted exam films have been introduced successfully in our country and especially worldwide. Thus, I would consider this stream or trend in question as the most important development of Hungarian animation in the 2010s.

If I should point at the works of one artist, I would definitely choose Réka Bucsi’s films. Symphony No. 42, Love and Solar Walk are the animated films she is most recognized of (Symphony No. 42 even came very close to be an Academy Award nominee), and to me they seem to emerge from the otherwise also excellent stream of films made by her workfellows and friends (including Zsuzsanna Kreif, Luca Tóth, Nadja Andrasev, Judit Wunder to name but a few). Her films are very playful and philosophical at the same time, and their linking to surrealistic fantasy and absurd humour is very precious. There are many similarities between her films (considering stylistic and narrative elements), but essential differences can be discovered as well, so the dynamics of the similarities and the differences seem to delineate an easily recognizable and very richly layered auteurist approach.

And I think that prominent trend in the 2010's Hungarian animation is the rise of female animators. Talents like Tóth, Andrasev and Szöllősi in the previous question are all female and still there are many talented female animators. But, on the other hand, I also think that there are always many talented female animators in Hungary for a long time, but they are ignored by, at least, international critics or cinephiles including me because of the language problem and sexism. So, I want to ask about the position of female animators in Hungarian animation history. There have been many of them, or has the number of them increased only recently?

You see it correctly; the rise of female animation artists is noticeable considering Hungarian animation in the 2010s. The “newest new wave”, which I mentioned in my previous answer, is definitely dominated by women. And this is not merely the question of some kind of “headcount”. Their artistic visions also offer approaches which seem to be original in the aesthetics of Hungarian animation. Even if each of them has a very personal style, it seems to be common that their aspiration is to deal with issues of sexuality and gender. Works such as Luca Tóth’s Superbia and Lidérc úr / Mr. Mare, Judit Wunder’s Kötelék / Bond, Nadja Andrasev’s A nyalintás nesze / The Noise of Licking and Szimbiózis / Symbiosis, Anna Katalin Lovrity’s Vulkánsziget / Volcano Island or Flóra Anna Buda’s Entrópia / Entropy, to mention just the most emblematic animations of this trend, are all centred upon the aforementioned issues in very different ways and by using rather individual approaches. So, this is definitely a new “spot” on the “canvas” of Hungarian animation.

But we must not forget about the female animation artists preceding them. In spite of the fact that Hungary’s animated film making was dominated by male artists for decades, significant female artists were working in this field as well. From the Communist era, we can mention at least three female directors who succeeded in making a very personal ouvre. In Budapest, Katalin Macskássy and Dóra Keresztes made immediately recognizable animated short films from the 1970s. The speciality of Katalin Macskássy was a very unique kind of animated documentary, which means that she used hundreds of drawings by children as the visual components of the films, and the sound consisted of interviews made with the children about their lives, their family, or what they think about the future, or even what they know about our holidays (Gombnyomásra / Push Button, „Nekem az élet teccik nagyon” / “I Think Life is Great Fun”, Ünnepeink / Our Holidays). The animated films of Dóra Keresztes offer the audience colourful landscapes of dreamlike worlds where figures and spaces are in constant shape-shifting; her visionary style is connected to folklore, Surrealism and nursery rhymes (Holdasfilm / Moon Film, Garabonciák / Wizards). The third female director is Mária Horváth, one of those artists who contributed to the establishment of the studio in Kecskemét. Mária Horváth’s films are more eclectic than the works of the aforementioned female directors; however, similarly to Keresztes, she is also very interested in the world of dreams, poetry and the fantasies of childhood, but the devices of her films – especially their visual tools – are quite variable. Her first film, Az éjszaka csodái / Miracles of the Night was based on a surrealistic poem by the Hungarian poet, Sándor Weöres, and it was one of the first international successes of the studio in Kecskemét (it won the 2nd prize in Ottawa). After that Mária Horváth continued with poetic short films such as Zöldfa utca 66 / Greentree Street 66 or Állóképek / Stills. She is also one of the leading directors of Hungarian Folk Tales. (We could also mention from this period the name of Ágnes Háy, who did not belong to the realm of the so-called official animated film making, and as an experimental film maker she made one of the earliest attempts in Hungary to use clay during the animation process.)

Significant female directors also showed up right after the end of Communism, during the 1990s and the 2000s. Without being exhaustive, we should mention the following names. Éva M Tóth, who I referred to when I spoke of the research available about Hungarian animation, has developed a very expressive imagery (based on the contrast of black and white) and a sensual style in her whirling visions (especially in Jelenések / Revelations). Kinga Rofusz made – among other films – the sad yet beautiful Arlequin, a very sophisticated film about loss, pain and memory. Zsófia Péterffy’s Kalózok szeretője / Lover of Pirates, a rather disquieting paint animation based on the ballad of François Villon, was awarded at the Venice Film Festival. Gizella Neuberger, who primarily is a background artist at Kecskemétfilm, made quite interesting experimental animations as a director, including a little-seen short film which I would dare to evaluate as the most underrated Hungarian animated film made in the last decade: it is A zöldségleves / Vegetable Soup, a very playful psychedelic vision. Finally, let me mention Katalin Glaser as well, whose exam film was the mesmerizing FIN, and then she continued with Három nagymamám volt / I had Three Grandmothers, one of the most important and the loveliest Hungarian animated short films from the 2010s. As I said earlier, the list of talented female animation artists is not complete at all with these names. I basically mentioned those artists whose works can be considered as the most significant and which I am the most familiar with.

From outside of Hungary, one of the most famous animators for the world cinephiles is Jankovics Marcell. I'm always impressed with his liberating, iridescent style of animation when I watch "Sisyphus" or "Fehérlófia". And especially "Fehérlófia" is re-released in America this year, getting more attention from world cinephiles. But, how are he and his films accepted in Hungary now? And I want to know about your honest opinion on him.

Let me begin with a personal note. Last year I was honoured by the proposal to write an extended essay about the animated films of Marcell Jankovics, and the text was published in a beautiful album which summarizes his ouvre (not just Jankovics’s animated films but his works as art and cultural historian as well). So I studied his animated films very closely, and as I also expressed it in the essay, I am a fan of his animated films, and I am sure many people would say the same in Hungary, and even all around the world.

Jankovics has created some of the most important Hungarian animations in every production types of the animated film. We have already mentioned his most famous short films, Sisyphus and Küzdők, and the series Hungarian Folk Tales would be completely different without his contribution, as he had the idea that the visual style of every episode should follow the decorative patterns of Hungarian folklore. He was the director of Hungary’s first full-length animated feature, titled János vitéz / Johnny Corncob, released in 1973, which was a turning point in his career. Jankovics decided that his films in the future should be connected to the Hungarian cultural heritage, and after that he turned to ornamental animation almost exclusively. (His early animations belong to the caricatural animation, including the excellent Hídavatás / Inauguration, but eventually Jankovics disowns most of them.) However, he tends to use different variations of the ornamental style, he deliberately did not develop a personal style, as his conviction is that he has to elaborate the specific style most fitting to the film he creates at a certain moment. Even if János vitéz and later Jankovics’s full-length animated films such as Fehérlófia, Ének a csodaszarvasról / Song of the Miraculous Hind, Az ember tragédiája and his series, including Hungarian Folk Tales, Mondák a magyar történelemből / Legends from the Hungarian History and Toldi (which is still in progress), do rely on Hungarian folklore, history and literature, some of his most successful films are deeply personal and universal at the same time (especially Sisyphus and Küzdők). Jankovics is a kind of workaholic, and in the 1980s he started a “secondary career” as an art and cultural historian. He published hundreds of essays and dozens of books, especially about the interpretation of symbols in general and specific symbols in particular (for example, he wrote entire books about the symbols of the Sun and the tree, respectively). As you can see, his fields of interest as a researcher are strongly connected to his animated film making. For instance, the symbolical elements dominate the extremely intensified visual stylization of Fehérlófia.

Something should be noted about the reception of his full-length animated films. Among them only the first one was a great success and was generally well received critically in Hungary. János vitéz still remains one of the best Hungarian animated films, while the opinions about the follow-ups are more divided. Maybe the reception of Fehérlófia is the most interesting, because it was not a great success like its predecessor, but by many people – including me – it is considered as the animated masterpiece of Jankovics, and it has developed a cult. The director is especially proud that he knows about little children who are somehow “addicted” to Fehérlófia, because its hallucinatory imagery reminds them of their own dreams! As you mentioned, thanks to the restoration and re-releasing of Fehérlófia, I am sure it will impress more and more people in the whole wide world.

The full-length animations which he made after the 1990s have not been re-evaluated yet. Ének a csodaszarvasról was not very well received when it was premiered, and to a certain degree it is understandable due to its problems with rhythm and the overcrowded narrative structure, yet some of the most amazing visual elements of the Jankovics-ouvre (somewhere they were labelled as ‘trippy’ scenes) can be seen in this film. As far as I know, of his full-length films Ének a csodaszarvasról is still the least-known internationally. I think that Az ember tragédiája was underrated when it was released, and I am convinced – or at least I hope – it will be re-evaluated, similarly to what happened to Fehérlófia. This monumental (160 minutes long!) animated film is based on the profoundly philosophical play written by Imre Madách in the second half of the 19th century. Its making process lasted more than two decades! Jankovics planned the adaptation from the beginning of the 80s, the first scenes were made at the end of the same decade, and the whole film was finished – as I have already mentioned that – in 2011. (In animation history maybe only Richard Williams was the artist who spent more years finishing his dream project, but unfortunately The Thief and the Cobbler does not exist in the form that Williams originally wanted to have if I am not mistaken.) The adaptation made by Jankovics does not stick only to the original text; the visual layer is filled with several anachronisms and thus the animated version is not just an “ordinary” adaptation but a brave reinterpretation of the original work as well (even if it has some unevenness, inevitably). It also summarizes the breathtaking knowledge Jankovics has about the history of mankind in general and art history in particular; in each of the episodes, different styles are used, but every style is based on the fine arts of those periods in which the episodes take place. Az ember tragédiája is not just about the past at all, it offers some very lively warnings about the possible future (and the present we live in). As we (I mean we globally) sink deeper and deeper day by day into a nightmarish world which seems to be concocted by Franz Kafka, George Orwell and Luis Buñuel together, certain parts of the animated film version seem alarmingly up-to-date, such as the end of the London episode, the weird danse macabre, and the stark dystopia of the next episode, the so-called Falanster. Maybe this is a pessimistic approach (which I would not consider as something distant from me), but we can see the world we live in as a transitional phase: the danse macabre slowly but surely dissolves into the dystopia. (But maybe I am wrong. I hope so.) Finally, we should remember that, his ouvre of animated films is not complete yet, as he is currently working on Toldi.

Personally, one of the most favorite Hungarian animators is Varga Csaba. Recommended by a Hungarian animator Szöllősi Anna, I watched his short "A szel" and I'm wholeheartedly moved. Diverse images overlap each other beautifully and strangely, sublimated into the profound meditation on human imagination. And next, I watched "Bestiak" and I'm surprised how drastically different it is from "A szel", yet truly a bombastic masterpiece. So, I want to know about his life and his works more detailedly. How are he and his works evaluated by Hungarian cinephiles actually?

I am very glad you mentioned Csaba Varga’s A szél / The Wind, as it also belongs to the best and most important Hungarian animated films ever created. It is not a coincidence you were surprised how different these two of his films are. Looking at the ouvre, Csaba Varga is one of those Hungarian animation directors whose works are quite eclectic, in fact, as his former colleagues and friends repeatedly claimed that he did not choose the same way twice when he made animated films. So, on the surface his animated films offer a wide range of approaches, styles and forms. As far as the latter is concerned, Csaba Varga was not only a master of drawn animation, as A szél clearly shows this, but he was one of the first directors in Hungary who began to make animations using clay. His clay heroine, called Auguszta, was introduced in a short film titled Ebéd – Kedvesem főz / The Luncheon – My Darling is Cooking at the beginning of the 1980s, and later the clumsy lady became the main character of a comical series. Csaba Varga also made a rather uncanny animated series using other variants of stop-motion animation (especially object animation), titled Szekrénymesék / Tales from the Cupboard. Its imagery is quite close to the ultra-creepy world of the Czech genius, Jan Švankmajer’s animations.

The series Auguszta shows the remarkably grotesque humour of Varga, while his drawn animation delineates a meditative, even philosophical approach. According to some, and here I have to refer to the essay of Anna Ida Orosz published after Varga passed away 8 years ago, under the very eclectic surface, there are some recurring motifs which can be discovered in most of Varga’s animated films. These motifs are centred on the topic of time, the passing of time, or – as Anna Ida wrote – the continuous present. His films such as A szél and the similarly mesmerising Időben elmosódva / Fading in Time are maybe his most compelling visual inquiries about the mysteries of time. Also, let us not forget that he was one of the great organizers in the history of Hungarian animation. Originally, he studied to be a mathematics and arts teacher, and during the 1970s, he was the leading figure of the group the members of which made animated films in Pécs as amateur film makers. His studio, called Yxilon, was later – in 1979 – reorganized as the second rural studio of Pannónia Film Studio, and Varga was the head of it till the middle of the 1980s.

The studio established in Pécs became undeservedly little-known, maybe a little forgotten, during the following decades, so let me say a few words about it. Beside Csaba Varga, there were very intriguing, if lesser-known artists as well. The team of the studio was strengthened by, to name but a few, Ágnes Pásztor, Károly Kismányoky, Ferenc Ficzek, Tamás Baksa, Nándor Markó, Károly Kása Papp. The short films made there were not unlike Csaba Varga’s own films, mostly they were experimental animations (see for example Ferencz Ficzek’s enigmatic yet rather captivating Hátrahagyott kijáratok / Exists Left Behind), and beside the series of Auguszta, the episodes of a very easily recognizable comical series, titled Trombi és a Tűzmanó / Trombi and the Fire Goblin, were also made in the studio in Pécs about a brigade of firemen (all of whom are anthropomorphic animals). At the very end of the 1980s, even a full-length animated feature was made in Pécs, a parody of the story of King Arthur, titled Sárkány és papucs / Dragon and Slippers. Later, after the end of Communism, when the studio became independent as Funny Film Ltd. and was headed by Tibor Hernádi, their main product was the series of quite comical commercial animations for the energy drink named Red Bull. Till the closing of the studio in 2013, 130 episodes of these commercial cartoons were made there. One of the former collaborators of the studio, a dear friend of mine, Andrea Kardos did a lot to draw attention to the animated legacy of Pécs. She made a regular exhibition which shows the relics of the studio and summarizes the story of animated film making in Pécs. With this short bypass, I tried to emphasize that the history of Hungarian animated film cannot be complete without examining the role of the studio established in Pécs.

Returning to Csaba Varga, it is quite important that he was the first one (cooperating with András Erkel) who established a private animation studio during the Communist era. He did this in 1988, just before the end of Communism. Varga Studio, located in Budapest, became one of the leading animation studios after the disintegration of Pannónia Film Studio in the 1990s. On the one hand, Varga Studio had dozens of jobs from foreign countries, mainly from Europe but from America as well, and on the other hand it encouraged experimental animation, inviting several talented young artists mostly from Central and Eastern Europe. For example, Milorad Krstić made his hilarious My Baby Left Me at Varga Studio, which became an international festival favourite at that time. (Later Milorad Krstić made the full-length animated film Ruben Brandt, a gyűjtő / Collector Ruben Brandt, which gained international acclaim, as you mentioned too). Varga himself, after he directed several experimental short films in the 1990s, at the very end of the century made the half-hour long clay animation adaptation of Don Quijote (1999), in which the protagonist was a kind of bittersweet self-portrait. After that, Varga retired from animated film making. Not unlike Marcell Jankovics, he dedicated himself to historical research instead; he published several books on topics such as ancient Hungarian history and the ancient history of language and writing. He was an exceptional person; his legacy is ranked among the most intriguing achievements of Hungarian animated film.

How is the current situation of Hungarian animation? From outside, it seems good. Many talents appear at prestigious film festivals like Tóth Luca at Cannes, Andrasev Nadja at SXSW and Szöllősi Anna at Sarajevo. But from inside, how do you see the current situation?

It is a little hard to say something truly valid about this question as a person who is interested in the examining of animated films, not in the making of them. I mean, the problems that the film makers have to face appear before they start to make the films or during the making of the animations, while I see the problems – and I refer to rather different sort of problems – when the films are finished and released :D This is also a very complex question.

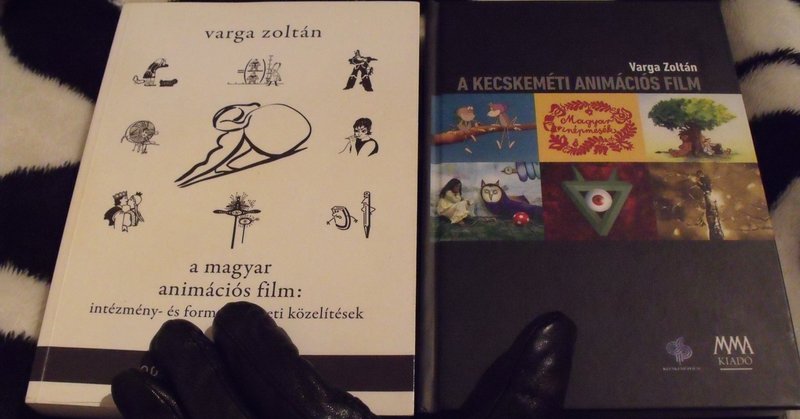

So, I hope you do not mind if I borrow some thoughts from the artists themselves. Last year, Magyar Művészeti Akadémia published a very useful book, edited by József Fülöp and Tamás Kollarik, titled Magyar animációs alkotók / Hungarian Animated Film Makers. It consists of 19 interviews with people who work (or worked) in the field of the animated film (most of them are directors but some of them are also producers and/or heads of studios). Many of them emphasize that there are unsolved problems in several areas, including the financing, the producing and the distribution of animations. The lack of proper funding and the lack of certain specialists frequently cause serious challenges. They find the lack of animators (those who have to design the motions, the movements) especially problematic, and there are not many screen-writers or producers who specialize in animated film making either. Due to the fact that the audience all over the world is overwhelmed by the incredible amount of every kind of moving pictures (including animation), it is much harder to find the public than it was earlier.

However, it is still true that there are very promising talents who will undoubtedly get glory to Hungarian animation; I highlighted the successes of Réka Bucsi, you mentioned other talents, so there is no doubt that contemporary Hungarian animation definitely has potential concerning talents. Some of the most important directors who began their careers in the previous century are still working, including Jankovics, István Orosz and Ferenc Cakó, to name some of them. It is also true that there are several full-length animated films in progress (including a dystopian science-fiction, titled Műanyag égbolt / Plastic Sky, directing by Sarolta Szabó and Tibor Bánóczki, or a documentarist animation, titled Kék pelican / Blue Pelican, directing by László Csáki, who is known for his unique animations made by using chalk), and there are many series in progress as well, first and foremost the long awaited Toldi.

So, as a concluding note, I would say that those optimistic opinions which envision a possible new golden age of Hungarian animated film may be wrong, or at least they are exaggerating. Yet, Hungarian animation may have many surprises up its sleeve. We came to praise Hungarian animated film making, not to bury it. Thank you very much for the opportunity of this interview!

私の文章を読んでくださり感謝します。もし投げ銭でサポートしてくれたら有り難いです、現在闘病中であるクローン病の治療費に当てます。今回ばかりは切実です。声援とかも喜びます、生きる気力になると思います。これからも生きるの頑張ります。