China Pathfinder: Q1 2024 Update, Rhodium Group, May 16, 2024.

Daniel H. Rosen, Matthew Mingey, Camille Boullenois and Laura Gormley

External relations can only be positive if China demonstrates convergence with market norms. Based on the China Pathfinder framework, the opposite is in evidence, and market economies will discuss how to react at the coming G7 leader’s summit.

China Pathfinder is a multiyear initiative from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and Rhodium Group to measure China’s economic system relative to advanced market economies in six areas: financial system development, market competition, modern innovation system, trade openness, direct investment openness, and portfolio investment openness. To explore our data visualization and read our 2023 annual report, please visit the Pathfinder website.

Debate about China’s domestic demand conditions came to a boil during the first quarter of 2024, as positive messages contrasted rising exports and political complaints from Europe, Asia, North America, and (in the form of anti-dumping duties) elsewhere. Beijing worked hard to maintain the more constructive economic narrative that flowed from the November 2023 Biden-Xi meeting on the sidelines of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in San Francisco. The positive vibes emanated from climate cooperation and global debt talks, bolstered by relatively restrained Chinese behavior around Taiwanese elections. However, this warming trend was tenuous: economic and financial market headwinds inside China cast a shadow on external expectations, as concerns about the trade spillovers resulting from weak Chinese domestic demand mushroomed. External relations can only be positive if China demonstrates convergence with market norms. Based on the China Pathfinder framework, the opposite is in evidence, and market economies will discuss how to react at the coming G7 leader’s summit in Apulia, Italy in June.

China’s macro story in the first quarter of 2024

At the start of the year, Beijing declared that its 2023 gross domestic product (GDP) growth results came out perfectly as planned, just above the target floor, at 5.2%. That occasioned a growing chorus of debate, discussion, and skepticism. Many of the components said to be growing, including the government fiscal impulse, looked flat or negative to economists inside and outside China. Despite these questions, Beijing revealed the same playbook for 2024 over the first quarter: the economy would grow at 5%, bolstered by active fiscal support.

On the positive side, because in our view 2022 and 2023 were extremely slow or flat growth years (0-1.5%), we expect China did see a modest economic improvement in the first quarter of 2024. After years of property crisis, the sector was more likely to see cyclical stabilization. In the aggregate, property turned in yet another negative quarter, but some indicators finally turned positive. And strength in the electric vehicle (EV), battery, and renewable energy sectors was real.

Cyclical improvements and a handful of bright spot industries are not enough to build a sustainable future on. Outside China, both advanced and (surprisingly) developing economies stepped up actions this quarter to address trade spillover concerns in light of weak domestic demand and anemic support policies for household and government consumption. The first quarter started with advanced economy emissaries urging Beijing to build demand support into its 2024 work plan so it was clear to see, instead of supporting only suppliers; by the end of the quarter China’s disinclination to do that, and its “overcapacity problem,” dominated the discussion. The United States, European Union, and Japan have publicized their systemic concerns about China’s capacity patterns in upstream areas like steel, midstream areas like legacy chips, and finished downstream goods like electric vehicles, windmills and much else. They are talking about unilateral, bilateral, and (with the G7 leaders summit approaching in mid-June) plurilateral options to push back.

The most important event on the annual policy calendar, the National People’s Congress, did not endorse policy measures to stimulate demand, and in fact implied support for a rising trade surplus instead. The externally oriented China Development Forum, an exchange with foreign business leaders occurring since 2000, offered positive guidance for multinational business.

But behind closed doors many foreign firms reported receiving continuing pressure to export, at a loss if necessary, if they wanted to maintain their position in the Chinese marketplace. Official media insisted that President Xi Jinping was the standard bearer for the same reform and opening imperative that Deng Xiaoping had enshrined. However, from our Pathfinder perspective, the official call for balanced growth was not supported by credible plans to get back to unfinished imperatives. In 2013, Xi had called for state ownership reform, changes to corporate governance, fiscal, and tax reforms, and much else, but these were never carried through.

A look at Q2 trendlines

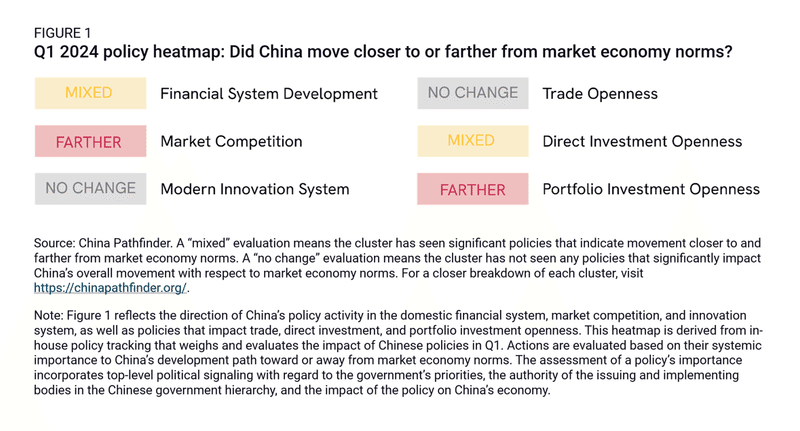

As we explain in annual China Pathfinder reports, a contestable Chinese regulatory state, with checks on concentrated one-party political power, is essential if the nation is to achieve potential growth. Figure 1 summarizes our impressions of movement toward or away from the market economy norms that characterize that outcome, in the first quarter of 2024. The measures Beijing announced or demonstrated (discussed in more detail in Part 2 just below) were at best a stop-gap, and at worst counter-productive, because they are delaying the inevitable.

January-March 2024 policy specifics: Putting on a brave face

Financial system

Stability trumped efficiency in China’s financial system this quarter, as state related investment entities (“the national team”) bought securities in the capital markets to counteract market sentiment disappointed by policy and economy signals. Official rhetoric on the need to improve growth conditions was not matched by hoped-for policies. The March National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Congress (CPPCC)—together the “Two Sessions” that mark the apex of the annual policy cycle—were an important opportunity for Beijing to signal pro-growth intentions but offered little.

Despite hopes that the NPC would announce major fiscal stimulus, government support in the first quarter of 2024 was weaker than expected, and even weaker than the equivalent period in 2023. Beijing presented a range of measures and nominal increases in deficit targets and bond quotas. But little of this support will boost consumption. The central government remains unwilling to use the balance sheet of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) to stimulate, instead telling local authorities to once again be creative in finding resources, as they had for years by selling land to property developers. Consequently, the grave fiscal unease hanging over local government spending remains. The largest measure that was announced at the NPC—issuance of one trillion RMB in special treasury bonds—is meant not to relieve credit stress but to finance industrial policy in specific technology areas.

This fiscal stance contrasted with monetary policy developments during the period. China is now unable to drive the same pace of credit and investment growth as in the past, given the massive existing size of the banking system ($58 trillion in assets, around 55% of global GDP), which means that Beijing can no longer manage the economy by allocating credit growth through the financial system as it used to. Instead, officials are resorting to unconventional monetary easing measures, using the PBOC’s balance sheet and targeted liquidity injections, rather than interest rate cuts and adjustments to bank required reserve ratios. The PBOC did cut required reserve ratios in January, but this was largely an attempt to prop up the equity market.

The balance sheet expansion may improve liquidity conditions, but it also is spilling back into shadow banking assets as well, and encouraging speculative positions in China’s bond market. All of this is channeling credit to the financial sector rather than the real economy, as credit demand among private firms remains weak. Nevertheless, reductions in mortgage rates may also help to slow the pace of household deleveraging and improve household consumption, even if few homebuyers are prepared to jump back into China’s battered housing market.

Market competition

As reflected in the financial system discussion, Beijing’s Q1 policy focus was squarely on encouraging industrial production with supply-side measures, rather than balancing that bias with more demand-side support for household consumption and government transfers. This was at odds with mounting global concerns about rampant Chinese industrial overcapacity. Support for failing enterprises through subsidies and credit forbearances has raised the share of loss-making industrial enterprises from 15% in 2021 to 22% in 2023. The March 2024 Government Work Reportshowed no sign of changing course, instead strengthening investment guidance for key sectors and thus further enhancing the role of government in resource allocation.

China continued a “charm offensive” in the quarter to revive or at least stabilize inward foreign direct investment (FDI), which has been falling. In February, the State Council (the topmost governmental administrative body) issued a plan to attract foreign investment including pledges to improve the business environment, ease administrative burdens, expand market access in key industries, and level the playing field for foreign companies. At the NPC, the Government Work Report amplified this message, with the usual language that “state-owned enterprises, private businesses, and foreign-funded companies all play an important role in China’s modernization drive.” At the end of March, the China Development Forum was convened for foreign CEOs to interact with Chinese leaders in Beijing. While the businessmen (they were entirely men) appreciated the pledges, they generally communicated a wait and see attitude in private readouts on the meeting. Market competition depends on transparency, which remains lacking: emblematically, Premier Li Qiang declined to hold a press briefing at the annual parliamentary meetings, for the first time in three decades.

Innovation

China ramped up government support for high-tech sectors, expanding fiscal spending on science and technology (S&T) and doubling down on industrial policy practices that entail a stronger state intervention in the economy.

The March Government Work Report identified self-reliance in science and technology and modernization of the industrial system as the top priorities for 2024 (up from previous years). Accordingly, the central S&T budget for this year grew by 10%, the largest percentage increase of any major area of government spending. The central government also expects local officials to prioritize support for innovation despite their shrinking fiscal space.

The central government ramped up high-tech support through a mix of conventional and unconventional subsidies, including grants and tax support. A Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) policy from January outlined the development of high-tech industrial zones and new infrastructure, dedicated investment funds, and tighter guidance of bank loans and capital towards strategic sectors. Local governments quickly adopted their own support plans to implement those measures.

While the volume of Beijing’s support for innovation programs is huge, China also faces foreign tech pushback. Policies to limit technology transfer (in semiconductors), bifurcate data and ICT services, and block imports of e.g. EVs and renewable energy goods reached a new high this quarter. China argues that its support measures are a response to these foreign restrictions, an argument that foreign governments can also plausibly make.

Trade

China’s trade surpluses in overcapacity sectors made headlines this quarter. Support for the industrial sector while neglecting household and government consumption has driven overcapacity and a spike in exports—especially in volume terms, and particularly in green technologies like EVs and renewable energy sectors. The National People’s Congress in March signaled support for trade surplus growth rather than plans for structural adjustment. Premier Li’s Government Work Report focused on bolstering industrial production, particularly in manufacturing, and committed Beijing to assist companies in exporting their accumulating surplus to foreign markets through mechanisms like export credits and export credit insurance.

Beijing’s unresponsiveness has fueled concerns around the world. Overcapacity was a key point of discussion during US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s April China visit. The European Commission opened investigations into Chinese solar and wind subsidies. Brazil, India, Mexico, and South Africa all took anti-dumping action in Q1 to respond to China’s surge of cheap exports.

Rather than acknowledge concerns, China chose retaliation and defensive actions. A few weeks after the European Commission announced an investigation into Chinese EV subsidies, Beijing launched an anti-dumping probe into imports of brandy from the EU. China also initiated a World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute regarding US tax credits for electric vehicles and renewable energy. China also has offered an indirect response, arguing that its low-cost exports will reduce global inflation. Until China takes more effective steps to address the domestic supply/demand imbalance, however, foreign trade defense actions are likely to multiply.

Direct investment

According to Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM)data, utilized foreign direct investment in the period of January-February 2024 was down 19.9% on a year-on-year basis. This same period last year, China was reeling from the rapid spread of COVID-19, so one could have expected this year’s numbers to improve based on base effects. In 2023 inward direct investment growth dropped to lows not seen since 1993, and the trend continues year to date. Numerous indicators point to continued FDI withdrawal. We attribute this to a combination of explicit hostility to foreign and private business interests, lack of policy transparency, and falling macroeconomic growth expectations. Business environment challenges are not new, but fears of a long-term growth slowdown are.

To counter these dynamics, officials worked to revitalize foreign investor interest through a series of high-level dialogues and events in this quarter. In March, an inaugural “Invest in China” initiative was held, followed with roundtables in France and Denmark. After weeks of mixed signals about whether they would be received by high level officials, US business executives were afforded an hour-plus interaction with President Xi, following the 2024 China Development Forum. Promises of more market reforms were made in an effort to encourage foreign investment.

Alongside these public and private relations efforts, the State Council released a twenty-four-point plan in March. These measures build off a similar 2023 investment promotion plan and further develop targets outlined in the March 2024 Government Work Report. The measures include: reducing the foreign investment negative list of sectors closed to foreign investment, last updated in 2021; expanding the Catalogue of Encouraged Industries for Foreign Investment (aka the “Catalogue”); and other policies that offer incentives and liberalize restrictions for foreign-invested enterprises. However, these measures are generally sector-specific (with emphasis on manufacturing and a few service industries) rather than general, and implementing rules are a ways off. Additional policy developments sought to further calm foreign investor nerves. Most notably, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) released long-awaited regulations that eased restrictions on most cross-border data flows. Previous data rules were a major source of foreign compliance anxiety. Additionally, there are signs that implementation of provincial-level initiatives is underway, such as new MIIT guidancefor easing foreign investor participation in the telecom sector of pilot zones. Yet many expect these measures to under-deliver and are skeptical they will address the core business environment problems of over-securitization and local protectionism. The anti-espionage law continues to be cited as a serious barrier, as it fuels anxiety for foreign staff operating in China, suppresses market research activities, and makes it harder to obtain investment approval. Additional restrictions in Hong Kong under a new security law passed in March 2024 reinforce foreign investors concerns that they may be swept up in security-related measures.

Outbound FDI from China’s firms was strong in the first quarter of 2024. Non-financial outbound direct investment reported by MOFCOM was up 5.5% year-on-year in February, though this was below the double-digit growth rates of 2023. The Two Sessions reiterated priorities for consolidating and revitalizing the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which includes strengthening the role of policy finance. China continues to promote investment in new energy infrastructure and sectors along green technology supply chains, such as mining and processing for EV battery inputs, in Southeast Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa, and green tech manufacturing in the EU.

Portfolio investment openness

China’s equity bourse interventions this quarter highlight the pressure authorities are under to stabilize capital markets rattled by disappointing macroeconomic conditions. After starting the year with a precipitous one-month decline that soured the 2024 outlook, state-linked investors embarked upon a buying spree to stabilize pricing. In February, state-backed investors bought more than $50 billion in domestic equities and exchange-traded funds (ETFs). This was effective in stabilizing prices in the short term—stocks improved 20% in February on both announced and rumored interventions—but by the end of the quarter stock values were slipping again. Meanwhile, more speculative foreign capital sought out China’s bond market in the quarter to take advantage of unusual pricing for onshore US dollars, causing a marked contrast between portfolio outflows from equities and inflows into bonds. Even as policymakers looked to boost domestic ETFs, issuers limited trading in ETFs with foreign assets that have been deluged by retail investors seeking exposure to Japanese and US equities.

At the micro level, regulators cracked down on quantitative trading firms, limiting their ability to sell short and summoning many for mandatory “compliance training” in which they were admonished to avoid trading behavior that might negatively affect the market. The China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) also pledged to improve initial public offering (IPO) and compliance requirements and make it harder for some companies to list. This was meant to reassure investors, who remain skeptical of market volatility and concerned by allegations of financial misconduct by public firms, but contrasts sharply with measures taken last year to facilitate stock market listings of state-owned enterprises. It also contrasts with declining overseas listings in the wake of last year’s tighter rules on foreign IPOs.

Monetary policy support during the period has also prioritized support for the stock market. Besides cuts to mortgage rates in late February, which aimed to stimulate overall activity via the housing market, the PBOC moved to make more cash available in the market by cutting the reserve requirement ratio (RRR) in a hastily scheduled press conference on January 24, the biggest RRR cut since the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in China.

Cross-economy policy directions in Q1 2024

As goes property, so goes China. And after two years of declines that nothing could offset, stabilization is finally possible this quarter. But improvement is likely temporary. Beijing’s growth target (5%) is above trend potential under the best of circumstances in today’s China, and is particularly unlike if structural problems are not addressed. A modest recovery in unlikely to halt the foreign march towards “derisking,” whether understood as diversifying from over-reliance on a single supplier with monopoly-like market power, or as implementing economic security measures. The United States, Europe, Japan, and others are evaluating the potential shortfall in China demand and concluding it means trade spillovers: they plan to confront that. Fixing this macroeconomic imbalance will entail structural economic reforms, which is why the heatmap in Figure 1 showing no progress is concerning.

Looking ahead to midyear

China’s policies are triggering foreign trade defense responses more quickly today than in the past. This is because foreign observers have been watching China carefully since the end of zero-COVID policies, and did not base their economic and investment plans solely on China’s rosy official data. During previous periods when flagging Chinese demand led to overcapacity spillovers, China’s official GDP figures went little challenged. This includes in 2015, when official year-on-year measures of physical activity went flat, or 2018-19, when they went negative for almost eighteen months. Conversely, in 2023-24 analysts watched carefully for actual policy implementation, especially fiscal support for household consumption, and local debt restructuring that might clear the way for renewed government spending. Instead, official comments in the International Monetary Fund Article IV report and March 2024 Government Work Reportthat Beijing would under-stimulate consumption and government spending capacity, while encouraging further growth in net exports.

Knowing this export wave is coming creates an obligation to act for democratically elected leaders in market economies. That is the driver behind pledges to employ trade defense measures in advanced economy capitals. Self-protection is likely to be aimed at manufacturing of electric vehicles, green energy equipment, steel, chemicals and other products. This is not just a Group of Seven (G7) affair: South Africa, India, Brazil, and Turkey have announced new anti-dumping measures in the past month to address surging Chinese exports, and even Russia has announced trade measures to stem imports of Chinese vehicles with internal combustion engines. Beijing’s response centers on the technical definition of overcapacity (which is murky), its economies of scale, its present comparative advantages in making many of these products (leaving aside whatever past subsidies and mercantile trade policies brought that about), and the role of foreign firms themselves in building up the capacity China now enjoys.

These Chinese arguments were anticipated. US Treasury Secretary Yellen was prepared to respond to them when she focused on overcapacity on her April 2024 China trip. Also in April, the day after EU Executive Vice President Margrethe Vestager pledged to improve Europe’s response to systemic overcapacity, the European Commission released an updated, 700+ page report on Chinese economic distortions that require trade defense, replete with 3,535 footnotes.

The conversation has gone beyond whether trade defenses are merited to the question of how to respond, and how to do so in an appropriate, collective manner. Japan’s trade surpluses in the 1980s resulted in joint action by the United States, Canada, Britain, and other European powers to promote adjustment via coordinated exchange rate revaluations, intended to make foreign goods more cost-competitive in Japan and Japanese products more expensive abroad. These were the Plaza and Louvre Accords of 1985 and 1987, respectively. As observed at the time, border trade measures only offer stopgap solutions to imbalances; a real fix requires structural economic reforms inside the problem economy.

G7 leaders convene in Apulia, Italy, June 13-15, 2024, and will discuss China’s overcapacity. Measures including tariffs and anti-subsidies duties will surely be debated. G7 leaders might also ask if collective border barriers might compel Beijing to implement voluntary export restraints (VERs). In the sectors of greatest G7 concern (such as EVs, clean energy products, and legacy chips), China’s implementation of export licenses, export taxes, quotas, or other measures, could forestall the most serious foreign trade actions. For China to be taken seriously, it likely would need to also implement tangible policies to support domestic demand. Only this would address overcapacity from both sides.

But even a combination of VERs and domestic consumer stimulus, as hard as it is to imagine presently, would be just a down payment on reform. Structural reform in China can only be credibly undertaken over time. Unless there are far-reaching reforms of the financial system, as we have discussed in the Pathfinder annual reports, piecemeal trade promotion and near-term fiscal policies in China will not resolve long-term concerns.

Acknowledgements

Written by Daniel Rosen, Matt Mingey, Camille Boullenois, and Laura Gormley.

The authors wish to acknowledge the members of the China Pathfinder Advisory Council: Steven Denning, Gary Rieschel, and Jack Wadsworth, whose partnership has made this project possible.

Sophia Busch, Charles Lichfield, Josh Lipsky, and Jeremy Mark were the principal contributors from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center.