2022 Investment Climate Statements: China, U.S. Dept of State, 2022.

Executive Summary

In 2021, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was the number two global Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) destination, behind the United States. As the world’s second-largest economy, with a large consumer base and integrated supply chains, China’s economic recovery following COVID-19 reassured investors and contributed to high FDI and portfolio investments. The PRC implemented major legislation in 2021, including the Data Security Law in September and the Personal Information Protection Law in November.

China remains a relatively restrictive investment environment for foreign investors due to restrictions in key sectors and regulatory uncertainties. Obstacles include ownership caps and requirements to form joint venture (JV) partnerships with local firms, industrial policies to develop indigenous capacity or technological self-sufficiency, and pressures to transfer technology as a prerequisite to gaining market access. New data and financial rules announced in 2021 also created significant uncertainty surrounding the financial regulatory environment. The PRC’s pandemic-related visa and travel restrictions significantly affected foreign businesses operations, increasing labor and input costs. An assertive Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and emphasis on national companies and self-reliance has heightened foreign investors’ concerns about the pace of economic reforms.

Key developments in 2021 included:

The Rules for Security Reviews on Foreign Investments came into effect January 18, expanding PRC vetting of foreign investment that may affect national security.

The National People’s Congress (NPC) adopted the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law on June 10.

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) issued draft revisions to its Cybersecurity Review Measures to broaden PRC approval authority over PRC companies’ overseas listings on July 10.

China formally applied to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) on September 16.

On November 1, the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) went into effect and China formally applied to join the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA).

On December 23, President Biden signed the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. The law prohibits importing goods into the United States that are mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor in the PRC, especially from Xinjiang.

On December 27, the National Reform and Development Commission (NDRC) and the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) updated its foreign FDI investment “negative lists.”

While PRC pronouncements of greater market access and fair treatment of foreign investment are welcome, details and effective implementation are needed to ensure equitable treatment.

1. Openness To, and Restrictions Upon, Foreign Investment

Policies Towards Foreign Direct Investment

FDI has played an essential role in China’s economic development. Though the PRC remains a relatively restrictive environment for foreign investors, PRC government officials tout openness to FDI, promising market access expansion and non-discriminatory, “national treatment” for foreign enterprises through improvements to the business environment. They also have made efforts to strengthen China’s regulatory framework to enhance market-based competition.

MOFCOM reported FDI flows grew by about 15 percent year-on-year, reaching USD 173 billion, however, foreign businesses continue to express concerns over China’s pandemic restrictions. In 2021, U.S. businesses’ concerns with China’s COVID-19 restrictive travel restrictions were at the top of the agenda, along with concerns over PRC’s excessive cyber security and data-related requirements, preferential treatment for domestic companies – including state-owned enterprises – under various industrial policies, preference for domestic technologies and products in the procurement process, an opaque regulatory system, and inconsistent application of laws protecting intellectual property rights (IPR). U.S.-China geopolitical tensions were also cited as a significant concern. See the following:

American Chamber of Commerce China 2021 American Business in China White Paper

American Chamber of Commerce China 2021 Business Climate Survey

U.S.-China Business Council’s 2021 China Business Environment Member Survey

China’s International Investment Promotion Agency (CIPA), under MOFCOM, oversees attracting foreign investment and promoting China’s overseas investment. Duties include implementing overseas investment policy; guiding domestic sub-national and international investment promotion agencies; promoting investment in industrial parks at the national, subnational, and cross-border level; organizing trainings in China and abroad for overseas investment projects; and, engaging international and multilateral economic organizations, foreign investment promotion agencies, chambers of commerce, and business associations. The agency has offices worldwide, including CIPA Europe in Hungary, CIPA Germany, and a representative office in the Hague to promote investment in the Benelux area. CIPA maintains an “Invest in China” website which lists laws, regulations, and rules relevant to foreign investors. The China Association of Enterprises with Foreign Investments (CAEFI) is a non-profit organization overseen by MOFCOM. The association and corresponding provincial institutions have hotlines to receive foreign investor complaints.

Limits on Foreign Control and Right to Private Ownership and Establishment

Entry into China’s market is regulated by the country’s “negative lists,” which identify the sectors in which foreign investment is restricted or prohibited, and a catalogue for encouraged foreign investment, which identifies the sectors and locations (often less developed regions) in which the government encourages investment.

The Special Administrative Measures for Foreign Investment Access to Pilot Free Trade Zones (the “FTZ Negative List”) applies to China’s 20 FTZs and one free trade port.

The Special Administrative Measures for Foreign Investment Access (̈the “Nationwide Negative List”) came into effect on January 1, 2022.

The Industry Catalogue for Encouraged Foreign Investment (released December 27, 2020) encourages FDI inflows to key sectors, in particular semiconductors and other high-tech industries.

The Industrial Catalogue for Encouraged Foreign Investment in Western Region. The “encouraged list” is subdivided into a cross-sector nationwide catalogue and a separate catalogue for western and central regions, China’s least developed regions.

In restricted industries, foreign investors face equity caps or JV requirements to ensure control by a PRC national and enterprise. Due to these requirements, foreign investors that wish to participate in China’s market must enter partnerships, which sometimes require transfer of technology. However, even in “open” sectors, a variety of factors, including ability to access local government officials and preferences, enhanced ability to impact local rules and standards, perceptions of better understanding of the PRC market, and access to procurement opportunities, led many foreign companies to rely on the JV structure to operate in the PRC market.

Below are a few examples of industries where investment restrictions apply:

Preschool to higher education institutes require a PRC partner with a dominant role.

Establishment of clinical trials for new drugs require a PRC partner who holds the IPR tied to data drawn from the clinical research.

Examples of foreign investment sectors requiring PRC majority stake include:

Radio/television market survey.

Basic telecommunication services outside free trade zones.

The 2021 negative lists made minor modifications to some industries, reducing the number of restrictions and prohibitions from 33 to 31 in the nationwide negative list, and from 30 to 27 in China’s pilot FTZs. Notable changes included openings in the automotive and satellite television broadcasting manufacturing sectors. Sectors that remain closed to foreign investment include rare earths, film production and distribution, and tobacco products. However, the government continues to constrain foreign investors in a myriad of ways beyond caps on ownerships. For instance, in the pharmaceutical sector, while JV requirements were eliminated in the 1990s, foreign companies must partner with local PRC institutions for clinical trials. Other requirements that place undue burden on foreign investors include but are not limited to: applying higher standards for quality-related testing, prohibitions on foreign parties in JVs conducting certain business activities, challenges in obtaining licenses and permits, mandatory intellectual property sharing related to certain biological material, and other implicit and explicit downstream regulatory approval barriers.

The negative list regulating pilot FTZ zones will lift all barriers to foreign investment in all manufacturing sectors, widen foreign investor access to some service sectors, and allow foreign investment into the radio and TV-based market research sector. For the market research sector, caveats include a 33 percent foreign investor ownership cap and PRC citizenship requirements for legal representatives. While U.S. businesses welcomed market openings, foreign investors remained underwhelmed by the PRC’s lack of ambition and refusal to provide more significant liberalization. Foreign investors noted the automotive sector openings were inconsequential since the more lucrative electric vehicle (EV) sector was opened to foreign investors in 2018, whereas the conventional auto sector is saturated. Foreign investors cited this was in line with the government announcing liberalization mainly in industries that domestic PRC companies already dominate.

In addition to the PRC’s system for managing foreign investments, MOFCOM and NDRC also maintain a system for managing which segments of the economy are open to non-state-owned investors. The most recent Market Access Negative List was issued on December 10, 2020.

The Measures for Security Reviews on Foreign Investments came into effect January 18, 2021, revising the PRC’s framework for vetting foreign investments that could affect national security. The NDRC and the Ministry of Commerce will administer the new measures which establish a mechanism for reviewing investment activities across a range of sectors perceived to implicate PRC national security, including agriculture, energy and resources, cultural products, and more.

Other Investment Policy Reviews

China is not a member of the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), but the OECD Council established a country program of dialogue and co-operation with China in October 1995. The OECD completed its most recent investment policy review for China in 2022.

China’s 2001 accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) boosted its economic growth and advanced its legal and governmental reforms. The WTO completed its most recent trade policy review for China in 2021, highlighting FDI grew at a slower pace than in previous periods but remains a major driver of global growth and a key market for multinational companies.

Business Facilitation

Created in 2018, the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) is responsible for business registration processes. Under SAMR’s registration system, parties are required to report when they (1) establish a Foreign Invested Enterprise (FIE); (2) establish a representative office in China; (3) acquire stocks, shares, assets or other similar equity of a domestic China-based company; (4) re-invest and establish subsidiaries in China; and (5) invest in new projects. Foreign companies still report challenges setting up a business relative to their PRC competitors. Many companies offer consulting, legal, and accounting services for establishing operations in China. Investors should review their options carefully with an experienced advisor before investing.

Outward Investment

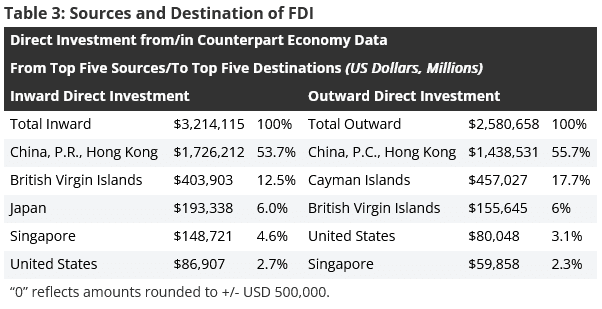

Since 2001, China has pursued a “going-out” investment policy. At first, the PRC encouraged SOEs to invest overseas, but in recent years, China’s overseas investments have diversified with both state and private enterprises investing in nearly all industries and economic sectors. China remains a major global investor and in 2021, total outbound direct investment (ODI) increased for the first time in four years to reach $153.7 billion, a 12 percent increase year-on-year, according to the 2020 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment .

China’s government created “encouraged,” “restricted,” and “prohibited” outbound investment categories to suppress significant capital outflow pressure in 2016 and to guide PRC investors to more “strategic sectors.” The Sensitive Industrial-Specified Catalogue of 2018 further restricted outbound investment in sectors like property, cinemas, sports teams, and non-entity investment platforms and encouraged outbound investment in sectors that supported PRC national objectives by acquiring advanced manufacturing and high-tech assets. PRC firms involved in sectors cited as priorities in the Strategic Emerging Industries, New Infrastructure Initiative, and MIC 2025 often receive preferential government financing and subsidies for outbound investment.

In 2006, the PRC established the Qualified (QDII) program to channel domestic funds into offshore assets through financial institutions. While the quota tied to this program has fluctuated over the years based on capital flight concerns, in 2021 the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) approved new quotas for 17 institutions under the program to allow a potential $147.3 billion in outbound investment.

In 2013, the PRC government established a pilot program allowing global asset management companies more opportunities to raise RMB-denominated funds from high net-worth PRC-based individuals and institutional investors to invest overseas. These programs include the Qualified Domestic Limited Partnership (QDLP) pilot program and the Shenzhen-specific Qualified Domestic Investment Entity (QDIE) program. In 2021, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) and SAFE expanded the pilot areas to at least seven jurisdictions and quotas for the QDLP to $10 billion, respectively. In April, the Shenzhen Financial Regulatory Bureau amended the Administrative Measures of Shenzhen for Implementation of the Pilot Program for Overseas Investment by Qualified Domestic Investors (“Shenzhen QDIE Measures”) to include investments in the securities market that aligns it with the QLDP program.

2. Bilateral Investment and Taxation Treaties

China has 107 bilateral investment treaties (BITs) in force and multiple free trade agreements (FTAs) with investment chapters. China has negotiated 24 trade agreements, with 16 of those agreements signed and in force. China has an additional eight FTAs under consideration. These agreements cover topics like expropriation, most-favored-nation treatment, and investment arbitration mechanisms. Relative to U.S.-equivalent agreements, PRC agreements generally offer fewer protections to foreign investors. For a list of China’s signed FTAs, please click here . For a list of China’s BITs, please click here.

In 2021, China and New Zealand signed a free trade agreement upgrade protocol and China formally deposited the ratification of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) with the ASEAN Secretary-General. On May 4, the European Commission decided to temporarily suspend efforts to ratify the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). The United States and China do not have a BIT and last held BIT negotiations in 2017. In 1984, the United States and the PRC concluded a bilateral taxation treaty. As of December 31, 2021, the PRC had concluded tax treaties/arrangements with 107 countries/regions. A full list of PRC- signed tax treaties is here . The PRC is one of the 141 members of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS).

3. Legal Regime

Transparency of the Regulatory System

One of China’s WTO accession commitments was to establish an official journal dedicated to the publication of laws, regulations, and other measures pertaining to or affecting trade in goods, services, trade related aspects of IPR (TRIPS), and the control of foreign exchange. Despite mandatory 30-day public comment periods, PRC ministries continue to post only some draft administrative regulations and departmental rules online, often with a public comment period of less than 30 days. As part of the Phase One Agreement, China committed to providing at least 45 days for public comment on all proposed laws, regulations, and other measures implementing the Phase One Agreement. While China has made some progress, U.S. businesses operating in China consistently cite arbitrary legal enforcement and the lack of regulatory transparency among the top challenges of doing business in China.

In China’s state-dominated economic system, the relationships between the CCP, the PRC government, PRC business (state- and private-owned), and other PRC stakeholders are blurred. Foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) perceive that China prioritizes political goals, industrial policies, and a desire to protect social stability at the expense of foreign investors, fairness, and the rule of law. The World Bank Global Indicators of Regulatory Governance gave China a composite score of 1.75 out 5 points, attributing China’s relatively low score to stakeholders not having easily accessible and updated laws and regulations; the lack of impact assessments conducted prior to issuing new laws; and other concerns about transparency.

For accounting standards, PRC companies use the Chinese Accounting Standards for Business Enterprises (ASBE) for all financial reporting within mainland China. Companies listed overseas or in Hong Kong may choose to use ASBE, the International Financial Reporting Standards, or Hong Kong Financial Reporting Standards.

While the government of China made many policy announcements in 2021 that will provide impetus to ESG reporting, stock exchanges on mainland China (not including Hong Kong) have not made ESG reporting mandatory. For instance, currently eighteen PRC companies are signatories to the UN Principles for Responsible Investment. While the PRC government did announce its green finance taxonomy known as China’s “Catalogue of Green Bond Supported Projects”, experts cited the taxonomy lacks mandatory reporting and verification. On November 4, the People’s Bank of China and the European Commission also jointly launched a sustainable finance taxonomy to create comparable standards on green finance products. Mainland ESG efforts were also primarily focused on environmental and social impact-related, and less so on governance-related reporting. China’s goal to peak carbon emissions before 2030 and reach carbon neutrality by 2060 will drive reporting on decarbonization plans and targets and could increase alignment with international standards such as those outlined in the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations. The PRC government also incorporated non-mandatory ESG-like principles into overseas development initiatives such as its signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) via its Guiding Opinions on Promoting Green Belt and Road Construction. For instance, the PRC adopted the Green Investment Principles (GIP) for greening investment for BRI projects; under this initiative members – including major PRC policy banks funding BRI projects – are expected to provide their first TCFD disclosure by 2023. Obstacles contacts cited include a shortage of quality data and ESG professionals, such as third-party auditors which are required to support evidence based ESG reporting.

In December, MEE issued new disclosure rules requiring five types of domestic entities to disclose environmental information on an annual basis, effective February 8, 2022. The rules will apply only to listed companies and bond issuers that were subject to environmental penalties the previous year and other MEE-identified entities, including those that discharged high levels of pollutants. Entities must disclose information on environmental management, pollution generation, carbon emissions, and contingency planning for environmental emergencies. These same companies and bond issuers must also disclose climate change and environmental protection information related to investment and financing transactions.

On June 28, the CSRC issued final amendments requiring listed companies disclose environmental penalties and encouraging carbon emissions disclosures. It also issued guidelines on the format and content of annual reports and half-year reports of listed companies, requiring them to set up a separate “Section 5 Environmental and Social Responsibility” to encourage carbon emission reduction related disclosure. In May, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) issued a plan for strengthening environmental disclosure requirements by 2025. Most contacts assessed investors are the key drivers of increased ESG disclosures.

International Regulatory Considerations

As part of its WTO accession agreement, China agreed to notify the WTO Committee on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) of all draft technical regulations. However, China continues to issue draft technical regulations without proper notification to the TBT Committee.

The PRC is also a member of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which entered into force on January 1, 2022. Although RCEP has some elements of a regional economic bloc, many of its regulatory provisions (for example on data flow) are weakened by national security exemptions.

On September 16, China submitted a written application to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) to New Zealand (the depositary of the agreement). The PRC would face challenges in addressing obligations related to SOEs, labor rights, digital trade, and increased transparency.

Legal System and Judicial Independence

China’s legal system borrows heavily from continental European legal systems, but with “Chinese characteristics.” The rules governing commercial activities are found in various laws, regulations, departmental rules, and Supreme People’s Court (SPC) judicial interpretations, among other sources. While China does not have specialized commercial courts, it has created specialized courts and tribunals for the hearing of intellectual property disputes (IP), including in Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Hainan. The PRC’s constitution and laws are clear that PRC courts cannot exercise power independent of the Party. Further, in practice, influential businesses, local governments, and regulators routinely influence courts. Outside of the IP space, U.S. companies often hesitate in challenging administrative decisions or bringing commercial disputes before local courts due to perceptions of futility or fear of government retaliation.

Laws and Regulations on Foreign Direct Investment

The PRC’s new foreign investment law, the FIL, came into force on January 1, 2020, replacing the previous foreign investment framework. The FIL provides a five-year transition period for foreign enterprises established under previous foreign investment laws, after which all foreign enterprises will be subject to the same domestic laws as PRC companies, such as the Company Law. The FIL standardized the regulatory regimes for foreign investment by including the negative list management system, a foreign investment information reporting system, and a foreign investment security review system all under one document. The FIL also seeks to address foreign investors complaints by explicitly banning forced technology transfers, promising better IPR, and the establishment of a complaint mechanism for investors to report administrative abuses. However, foreign investors remain concerned that the FIL and its implementing regulations provide PRC ministries and local officials significant regulatory discretion, including the ability to retaliate against foreign companies.

The December 2020 revised investment screening mechanism under the Measures on Security Reviews on Foreign Investments (briefly discussed above) came into effect January 18 without any period for public comment or prior consultation with the business community. Foreign investors complained China’s new rules on investment screening were expansive in scope, lacked an investment threshold to trigger a review, and included green field investments – unlike most other countries. Moreover, new guidance on Neutralizing Extra-Territorial Application of Unjustified Foreign Legislation Measures, a measure often compared to “blocking statutes” from other markets, added to foreign investors’ concerns over the legal challenges they would face in trying to abide by both their host-country’s regulations and China’s. Foreign investors complained that market access in China was increasingly undermined by national security-related legislation. While not comprehensive, a list of official PRC laws and regulations is here .

On June 10, the Standing Committee of the NPC adopted the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Countering Foreign Sanctions (“Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law” or AFSL). The AFSL gives the government explicit authority to impose countermeasures related to visas, deportation, and asset freezing against individuals or organizations that broadly endanger China’s “sovereignty, security, or development interests.” The law also calls for Chinese citizens and organizations harmed by foreign “sanctions” to pursue damages via PRC civil courts.

On October 13, MOF issued a circular prohibiting discrimination against foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) in government procurement for products “produced in China.” The circular required that suppliers not be restricted based on ownership, organization, equity structure, investor country, or product brand, to ensure fair competition between domestic and foreign companies. The circular also required the abolition of regulations and practices violating the circular by the end of November, including the establishment of alternative databases and qualification databases. This circular may have been intended to address the issuance of Document No. 551 in May by MOF and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) (without publishing on official websites), titled “Auditing guidelines for government procurement of imported products,” outlining local content requirements for hundreds of items, many of which are medical devices, including X-ray machines and magnetic resonance imaging equipment. It is unclear whether Document 551 will be rescinded or revised based on this circular. Additionally, the circular applies only to FIEs and does not provide fair treatment for imported products from companies overseas. While the circular does state FIEs should be afforded equal treatment, the circular does not address concerns about localization pressures created by Document 551. Further, the circular provides no guidance on what constitutes a “domestic product” and does not address treatment of products manufactured in China that incorporate content from other jurisdictions, key concerns for a wide range of U.S. firms.

FDI Requirements for Investment Approvals

Foreign investments in industries and economic sectors that are not explicitly restricted on China’s negative lists do not require MOFCOM pre-approval. However, investors complained that in practice, investing in an industry not on the negative list does not guarantee a foreign investor “national treatment,” or treatment no less favorable than treatment accorded to a similarly situated domestic investor. Foreign investors must comply with other steps and approvals such as receiving land rights, business licenses, and other necessary permits. When a foreign investment needs ratification from the NDRC or a local development and reform commission, that administrative body oversees assessing the project’s compliance with a panoply of PRC laws and regulations. In some cases, NDRC solicits the opinions of relevant industrial regulators and consulting agencies acting on behalf of domestic firms, creating potential conflicts of interest disadvantageous to foreign firms.

Competition and Antitrust Laws

In November 2021, the PRC government announced transformation of the Anti-Monopoly Bureau of the SAMR, renaming it the National Anti-Monopoly Bureau, adding three new departments, and doubled staffing. The National Anti-Monopoly Bureau enforces China’s Anti-Monopoly Law (AML) and oversees competition issues at the central and provincial levels. The bureau reviews mergers and acquisitions, and investigates cartel and other anticompetitive agreements, abuse of a dominant market positions, including those related to IP, and abuse of administrative powers by government agencies. The bureau also oversees the Fair Competition Review System (FCRS), which requires government agencies to conduct a review prior to issuing new and revising administrative regulations, rules, and guidelines to ensure such measures do not inhibit competition. SAMR issues implementation guidelines to fill in gaps in the AML, address new trends in China’s market, and help foster transparency in enforcement. Generally, SAMR has sought public comment on proposed measures, although comment periods are sometimes less than 30 days.

In October 2021, SAMR issued draft amendments to the AML for public comment. Revisions to the AML are expected to be finalized in 2022 and likely will include changes such as stepped-up fines for AML violations and specification of the factors to consider in determining whether an undertaking in the internet sector has abused a dominant market position. In February 2021, SAMR published (after public comment) the “Antitrust Guidelines for the Platform Economy.” The Guidelines address monopolistic behaviors of online platforms operating in China.

Foreign companies have long expressed concern that the government uses AML enforcement in support of China’s industrial policies, such as promoting national champions, particularly for companies operating in strategic sectors. The AML explicitly protects the lawful operations of government authorized monopolies in industries that affect the national economy or national security. U.S. companies expressed concerns that in SAMR’s consultations with other PRC agencies when reviewing M&A transactions, those agencies raise concerns not related to competition concerns to block, delay, or force transacting parties to comply with preconditions – including technology transfer – to receive approval.

Expropriation and Compensation

China’s law prohibits nationalization of FIEs, except under vaguely specified “special circumstances” where there is a national security or public interest need. PRC law requires fair compensation for an expropriated foreign investment but does not detail the method used to assess the value of the investment. The Department of State is not aware of any cases since 1979 in which China has expropriated a U.S. investment, although the Department has notified Congress through the annual 527 Investment Dispute Report of several cases of concern.

Dispute Settlement

ICSID Convention and New York Convention

China is a contracting state to the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID Convention) and has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (New York Convention). PRC legislation that provides for enforcement of foreign arbitral awards related to these two Conventions includes the Arbitration Law, the Civil Procedure Law, and other laws with similar provisions that have embraced many of the fundamental principles of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law’s Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration. However, in some disputes, PRC courts have refused to enforce arbitral awards they deem violate public interest and policy. Further, the process by which PRC courts – and ultimately the Supreme People’s Court – agree or refuse to enforce an arbitral award is opaque, and U.S. companies seeking enforcement of such awards are often left in the dark for years awaiting a determination.

Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS)

As China has become a capital exporter under its “Going Global” initiative and through infrastructure investments under BRI, its views on ISDS have shifted to allow foreign investors with unobstructed access to international arbitration to resolve any investment dispute that cannot be amicably settled within six months. PRC investors did not use investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanisms until 2007, and the first known ISDS case against China was initiated in 2011 by Malaysian investors. China is a signatory to the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) under the World Bank which provides arbitration under ICSID and United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) rules. China submitted a proposal on ISDS reform to the UNCITRAL Working Group III in 2019. Under the proposal, China reaffirmed its commitment to ISDS as an important mechanism for resolving investor-state disputes under public international law. However, it suggested various pathways for ISDS reform, including supporting the study of a permanent appellate body.

International Commercial Arbitration and Foreign Courts

PRC officials typically urge private parties to resolve commercial disputes through informal mediation. If formal mediation is necessary, PRC parties and the authorities typically prefer arbitration to litigation. Many contract disputes require arbitration by the Beijing-based China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC). Established by the State Council in 1956 under the auspices of the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT), CIETAC is China’s most widely utilized arbitral body for foreign-related disputes. Some foreign parties have obtained favorable rulings from CIETAC, while others have questioned CIETAC’s fairness and effectiveness. Besides CIETAC, there are also provincial and municipal arbitration commissions. A foreign party may also seek arbitration in some instances from an offshore commission. Foreign companies often encounter challenges in enforcing arbitration decisions issued by PRC and foreign arbitration bodies. In these instances, foreign investors may appeal to higher courts. The government of China and its judicial bodies do not maintain a public record of investment disputes. The SPC maintains an annual count of the number of cases involving foreigners but does not provide details about the cases.

In 2018, the SPC established the China International Commercial Court (CICC) to adjudicate international commercial cases, especially cases related to BRI. The CICC has established three locations in Shenzhen, Xian, and Suzhou. Despite its international orientation, CIIC’s 16 judges are all PRC citizens and Mandarin Chinese is the court’s working language. Parties to a dispute before the CICC can only be represented by PRC law-qualified lawyers, as foreign lawyers do not have a right of audience in China’s courts; and unlike other international courts, foreign judges are not permitted to be part of the proceedings. Judgments of the CICC, given it is a part of the SPC, cannot be appealed from, but are subject to possible “retrial” under the Civil Procedure Law.

China has bilateral agreements with 27 countries on the recognition and enforcement of foreign court judgments, but not with the United States. Under PRC law, courts must prioritize the Party’s needs, China’s laws and other regulatory measures above foreign court judgments.

Comprehensive data on how investments disputes over the last ten years involving a U.S. or international person was not available, however, there have been limited instances of PRC courts enforcing U.S. court (or other foreign court) decisions on the basis of reciprocal treatment. It is unclear what the trend on enforcement of foreign judgments will be.

Bankruptcy Regulations

The PRC introduced bankruptcy laws in 2007, under the Enterprise Bankruptcy Law (EBL), which applies to all companies incorporated under PRC laws and subject to PRC regulations. In May 2020, the PRC released the Civil Code, contract and property rights rules. Despite the NPC listing amendments to the EBL as a top work priority for 2021, the NPC has not released the amendments to the public. Court-appointed administrators – law firms and accounting firms that help verify claims, organize creditors’ meetings, list, and sell assets online – look to handle more cases and process them faster. As of 2021 official statements cited 5,060 institutional administrators and 703 individual administrators.

On August 18, the Law Enforcement Inspection Team of the Standing Committee of the NPC was submitted its report on the enforcement of enterprise bankruptcy to the 30th meeting of the Standing Committee of the Thirteenth NPC for deliberation. While the report is unavailable publicly, the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) website issued a press release noting the report found that from 2007 to 2020, courts at all levels nationwide accepted 59,604 bankruptcy cases, and concluded 48,045 bankruptcy cases (in 2020 there were 24,438 liquidation and bankruptcy cases). Of the total liquidation and bankruptcy cases recorded in that same period, 90 percent involved private enterprises. The announcement also cited the allocation of additional resources, including future establishment of at least 14 bankruptcy tribunals and 100 Liquidation & Bankruptcy Divisions and specialized collegial panels to handle bankruptcy cases. As of August 2021, bankruptcy cases are handled by 417 bankruptcy judges, 28 high people’s courts, and 284 intermediate people’s courts.

In 2021 the government added a new court in Haikou. National data is unavailable for 2021, but local courts have released some information that suggest a nearly 10 percent increase in liquidation and bankruptcy cases in Jiangxi province and about a 66 percent increase in Guangzhou, the capital city of Guangdong province. While PRC authorities are taking steps to address corporate debt and are gradually allowing some companies to fail, companies generally avoid pursing bankruptcy because of the potential for local government interference and fear of losing control over the outcome. According to the SPC, 2.899 million enterprises closed business in 2020, of which only 0.1 percent or 3,908 closed because of bankruptcy.

In August 2020, Shenzhen released the Personal Bankruptcy Regulations of Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, to take effect on March 1, 2021. This is the PRC’s first regulation on personal bankruptcy. On July 19, the Shenzhen Intermediate People’s Court of Guangdong Province, China served a ruling on Liang Wenjin approving his personal bankruptcy reorganization plan. This was the first personal bankruptcy case closed by Shenzhen Court since the implementation of the Personal Bankruptcy Regulations of Shenzhen Special Economic Zone and is the first personal bankruptcy reorganization case in China.

The Personal Bankruptcy Regulations is China’s first set of rules on personal bankruptcy, which formally establishes the personal bankruptcy system in China for the first time. At present, the Personal Bankruptcy Regulations is only applicable in Shenzhen. Numerous other localities have also begun experimenting with legal remedies for personal insolvency, in part to deter debtors from taking extreme measures to address debt.

4. Industrial Policies

Investment Incentives

To attract foreign investment, different provinces and municipalities offer preferential packages like a temporary reduction in taxes and/or import/export duties, reduced costs for land use, research and development subsidies, and funding for initial startups. Often, these packages stipulate that foreign investors must meet certain benchmarks for exports, local content, technology transfer, or other requirements. However, many economic sectors that China deems sensitive due to broadly defined national or economic security concerns remain closed to foreign investment.

As part of efforts to attract green investment, China and the EU issued a green investment taxonomy on the sidelines of the 26th U.N. Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) on November 4. The International Platform on Sustainable Finance (IPSF) Taxonomy Working Group issued the Common Ground Taxonomy- Climate Change Mitigation (CGT) to accelerate cross-border sustainability-focused investments and scale up the mobilization of green capital internationally. The CGT listed 80 economic activities across six industries as sustainable, including: (1) agriculture, forestry and fishing; manufacturing; (2) electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply; (3) construction; (4) water supply, and sewage, waste management and remediation activities; as well as (6) transportation and storage. The taxonomy includes criteria for calculating a project’s contribution to mitigating climate change. This taxonomy was the result of consultations held between the EU and China over the two years to conduct analyses between China’s “Catalogue of Green Bond Supported Projects” and the “EU Taxonomy Climate Delegated Act.” Green finance contacts reported the CGT would likely promote the issuance of cross-border green investment products and lower or avoid the cost of double certification. Environmental NGO contacts, however, noted the CGT was focused on climate change mitigation, without taking into consideration the principle of “do no significant harm.” The CGT is not legally binding for either the EU or China and is not formally endorsed by other members of the IPSF. Please see climate issues section for additional information on government incentives towards attracting green investment.

Foreign Trade Zones/Free Ports/Trade Facilitation

In 2013, the State Council announced the Shanghai pilot FTZ to provide open and high-standard trade and investment services to foreign companies. China gradually scaled up its FTZ pilot program to a total of 20 FTZs and one Free Trade Port (FTP), which are in all or parts of Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan (FTZ and FTP), Hebei, Heilongjiang, Henan, Hubei, Jiangsu, Liaoning, Shaanxi, Shandong, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Zhejiang provinces; Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai, and Tianjin municipalities. The goal of China’s FTZs/FTP is to provide a trial ground for trade and investment liberalization measures and to introduce service sector reforms, especially in financial services, that China expects to eventually introduce in other parts of the domestic economy. The FTZs promise foreign investors “national treatment” investment in industries and sectors not listed on China’s negative lists.

Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in China include: Shantou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, (Guangdong Province); Xiamen (Fujian Province) Hainan Province; Shanghai Pudong New Area; and Tianjin Binhai New Area.

In 2021, the PRC formulated the first negative list in the field of cross-border trade in services, effective in Hainan Free Trade Port. Separately, the PRC government has shortened the negative list for foreign investment in Pilot Free Trade Zones. In 2021, the seventh revision to the free trade zone negative list reduced close off sectors from 30 items to 27 items. Please see above section on negative lists for more details.

Performance and Data Localization Requirements

Performance Requirements

As part of China’s WTO accession agreement, the PRC government promised to revise its foreign investment laws to eliminate sections that imposed on foreign investors requirements for export performance, local content, balanced foreign exchange through trade, technology transfer, and research and development as a prerequisite to enter China’s market. In practice, China has not completely lived up to these promises. Some U.S. businesses report that local officials and regulators sometimes only accept investments with “voluntary” performance requirements or technology transfer that develop certain domestic industries and support the local job market.

Foreign companies also continue to report that PRC government officials may condition investment approval on a requirement that a foreign company transfer technology, conduct research and development (R&D) in China, satisfy performance requirements relating to exportation or the use of local content, or make valuable, deal-specific commercial concessions. Over the years, the United States has repeatedly raised concerns with the PRC about its restrictive investment regime. This sustained bilateral engagement has not led to a significant relaxation of China’s investment restrictions, apart from the financial services sectors.

Data Requirements

Various draft and recently finalized measures that implement the PRC’s Cybersecurity Law, Data Security Law, and Personal Information Protection Law, prohibit, or severely restrict cross-border transfers of certain information that are routine in the ordinary course of business and are fundamental to any business activity. These measures also would impose local data storage and processing requirements on companies designated as “critical information infrastructure operators” a term that the Cybersecurity Law defines in broad and vague terms. The PRC’s recently implemented Data Security Law and Personal Information Protection Law also include restrictions on cross-border data flows and requirements to store and process certain data locally. Given the wide range of business activities that are dependent on cross-border transfers of information and flexible access to global computing facilities, these developments have generated serious concerns among governments as well as among stakeholders in the United States and other countries, including among services suppliers.

Cybersecurity Law implementing regulations, to include Cybersecurity Review Measures implemented in February 2022, stipulate several circumstances where companies operating in the PRC must request a government review of their cross-border data transfers. Though these measures appear to apply similarly to domestic and foreign-based companies, the actual effect severely impacts multinational companies that must transfer data to regional or global offices in the normal course of business. Similar measures from June 2020 put in place a review process to regulate the purchase of ICT products and services by critical information infrastructure operators in the PRC. The review process considers the potential national security risks related to interruption of service, data leakage, and reliability of supply chains.

Use of ICT products and services is increasingly dependent on robust encryption, an essential functionality for protecting privacy and safeguarding sensitive commercial information. Onerous requirements on the use of encryption, including intrusive approval processes and, in many cases, mandatory use of indigenous encryption algorithms (e.g., WiFi and 4G/5G products), continue to be cited by U.S.-based investors operating in the PRC market as significant concerns.

5. Protection of Property Rights

Real Property

The government of China owns all urban land and only the state can issue long-term land leases to individuals and companies, including foreigners, subject to many restrictions. China’s property law stipulates that residential property rights renew automatically, while commercial and industrial grants renew if it does not conflict with other public interest claims. Several foreign investors have reported revocation of land use rights so that PRC developers could pursue government-designated building projects. Investors often complain about insufficient compensation in these cases. In rural China, the registration system suffers from unclear ownership lines and disputed border claims, often at the expense of local farmers whom village leaders exclude in favor of “handshake deals” with commercial interests. China’s Securities Law defines debtor and guarantor rights, including rights to mortgage certain types of property and other tangible assets, including long-term leases. PRC law does not prohibit foreigners from buying non-performing debt, but it must be acquired through state-owned asset management firms, and it is difficult to liquidate.

Intellectual Property Rights

The PRC remained on the USTR Special 301 Report Priority Watch List in 2022 and was subject to continued Section 306 monitoring. Multiple PRC-based physical and online markets were included in the 2021 USTR Review of Notorious Markets for Counterfeiting and Piracy. Of note, in 2021, the PRC government took steps toward addressing long-standing U.S. concerns on a wide range of IP issues, from patents to trademarks to copyrights and trade secrets. The reforms addressed the granting and protection of IP rights as well as their enforcement, and included changes made in support of the Phase One Trade Agreement. In September 2021, the CCP Central Committee and State Council jointly issued the “Outline for Building a Strong Intellectual Property Nation (2021-2035).” The Outline was China’s second long-term plan to promote IP development since the 2008 National IP Strategy Outline, and provided a high-level framework and specific goals for reforms of China’s entire IP ecosystem, including mechanisms to incentivize the creation and utilization of IP, as well as the systems and mechanisms for protecting and enforcing it. The State Council in October issued the “National 14th Five-year Plan IP Protection and Utilization Plan” which provided a list of IP-related tasks to achieve during 2021-2025. The Plan called for expedited revisions to the Patent Law, Trademark Law, Copyright Law, Anti-Monopoly Law, Science and Technology Advancement Law, and e-Commerce law, and to strengthen legislation in areas such as geographical indicators and trade secrets. In 2021, China’s IP progress also included the implementation of a judicial interpretation related to punitive damages on IP infringements, the gradual elimination of subsidies linked to patent applications, and administrative measures addressing trademark and patent protection and enforcement, as well as enforcement of copyright and trade secrets.

Despite these reforms, IP rights remain subject to Chinese government policy objectives, which appear to have intensified in 2021. For U.S. companies in China, infringement remained both rampant and a low-risk “business strategy” for bad-faith actors. Further, enforcement and regulatory authorities continue to signal to U.S. rights holders that application of China’s IP system remains subject to the discretion of the PRC government and its policy goals. High-level remarks by PRC leader Xi Jinping and senior leaders signaled China’s commitment to cracking down on IP infringement in the years ahead. However, they also reflected China’s vision of the IP system as an important tool for limiting foreign ownership and control of critical technology and ensuring national security. While on paper China’s IP protection and enforcement mechanisms have inched closer to near parity with other foreign markets, in practice, fair, transparent, and non-discriminatory treatment will very likely continue to be denied to U.S. rights holders whose IP ownership and exploitation impede PRC economic development and national security goals.

For detailed information on China’s environment for IPR protection and enforcement, please see the following reports:

USTR’s 2021 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers in China (see section on China)

For additional information about national laws and points of contact at local IP offices, please see WIPO’s country profiles at http://www.wipo.int/directory/en/.

6. Financial Sector

Capital Markets and Portfolio Investment

China’s leadership has stated that it seeks to build a modern, highly developed, and multi-tiered capital market. Since their founding over three decades ago, the Shanghai and Shenzhen Exchanges, combined, are ranked the third largest stock market in the world with over USD 12.2 trillion in assets. China’s bond market has similarly expanded significantly to become the second largest worldwide, totaling approximately USD 18.6 trillion. In 2021, China took steps to open certain financial sectors such as mutual funds, securities, and asset management, but multinational companies still report barriers to entering the PRC insurance markets. As an example, in September, Black Rock was the first firm given approval to sell mutual funds to PRC nationals as the first wholly foreign owned mutual fund. Direct investment by private equity and venture capital firms increased but also faced setbacks due to China’s capital controls, which obfuscate the repatriation of returns. Though the PRC is taking steps to liberalize its capital markets, PRC companies that seek overseas investment have historically tended to list in the United States or Hong Kong; PRC and U.S. regulations on exchanges and geopolitics may begin to impact this trend. As of 2021, 24 sovereign entities and private sector firms, including the Asian Development Bank, Hungary, and BMW, have since issued RMB 106.5 billion yuan, roughly USD 16.7 billion, in 72 “Panda Bonds,” Chinese renminbi (RMB)-denominated debt issued by foreign entities in China. China’s private sector can also access credit via bank loans, bond issuance, trust products, and wealth management products. However, most bank credit flows to state-owned firms, largely due to distortions in China’s banking sector that have incentivized lending to state-affiliated entities over their private sector counterparts. China has been an IMF Article VIII member since 1996 and generally refrains from restrictions on payments and transfers for current international transactions. However, the government has used administrative and preferential policies to encourage credit allocation towards national priorities, such as infrastructure investments and industrial policy.

Money and Banking System

The PRC’s monetary policy is run by the PBOC, the PRC’s central bank. The PBOC has traditionally deployed various policy tools, such as open market operations, reserve requirement ratios, benchmark rates and medium-term lending facilities, to control credit growth. The PBOC had previously also set quotas on how much banks could lend but ended the practice in 1998. As part of its efforts to shift towards a more market-based system, the PBOC announced in 2019 that it will reform its one-year loan prime rate (LPR), which would serve as an anchor reference for other loans. The one-year LPR is based on the interest rate that 18 banks offer to their best customers and serves as the benchmark for rates provided for other loans. In 2020, the PBOC requested financial institutions to shift towards use of the one-year LPR for their outstanding floating-rate loan contracts from March to August. Despite these measures to move towards more market-based lending, the PRC’s financial regulators still influence the volume and destination of PRC bank loans through “window guidance” – unofficial directives delivered verbally – as well as through mandated lending targets for key economic groups, such as small and medium sized enterprises. In 2020, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) also began issuing laws to regulate online lending by banks including internet companies such as Ant Financial and Tencent, which had previously not been subject to banking regulations. In 2021, PBOC and CBIRC issued circulars emphasizing the need to emphasize and encourage financial stability among real estate developers.

The CBIRC oversees the PRC’s 4,607 lending institutions, about USD 54 trillion in total assets. China’s “Big Five” – Agricultural Bank of China, Bank of China, Bank of Communications, China Construction Bank, and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China – dominate the sector and are largely stable, but has experienced regional banking stress, especially among smaller lenders. Reflecting the level of weakness among these banks, in September 2021, the PBOC announced in “China Financial Stability Report 2020” that 422 or 9.6 percent of the 4,400 banking financial institutions received a “fail” rating (high risk) following an industry-wide review in in the second quarter of 2021. The assessment deemed 393 firms, all small and medium sized rural financial institutions, “extremely risky.” The official rate of non-performing loans among China’s banks is relatively low: 1.7 percent as of the end of 2021. However, analysts believed the actual figure may be significantly higher. Bank loans continue to provide most credit options (reportedly around 63.6 percent in 2021) for Chinese companies, although other sources of capital, such as corporate bonds, equity financing, and private equity are quickly expanding in scope, reach, and sophistication in China.

As part of a broad campaign to reduce debt and financial risk, Chinese regulators have implemented measures to rein in the rapid growth of China’s “shadow banking” sector, which includes wealth management and trust products. These measures have achieved positive results. In December 2020, CBIRC published the first “Shadow Banking Report,” and claimed that the size of China’s shadow banking had shrunk sharply since 2017 when China started tightening the sector. By the end of 2019, the size of China’s shadow banking by broad measurement dropped to 84.8 trillion yuan from the peak of 100.4 trillion yuan in early 2017. PBOC estimated in January 2021 that the outstanding balance of China’s shadow banking was around RMB 32 trillion yuan at the end of 2020. Alternatively, Moody’s estimated that China’s shadow banking by broad measurement dropped to RMB 57.8 trillion yuan in the first half of 2021 and shadow banking to GDP ratio dropped to 52.9 percent from 58.3 percent at the end of 2020. Foreign owned banks can now establish wholly owned banks and branches in China, however, onerous licensing requirements and an industry dominated by local players, have limited foreign banks market penetration. Foreigners are eligible to open a bank account in China but are required to present a passport and/or Chinese government issued identification.

Foreign Exchange and Remittances

Foreign Exchange

While the central bank’s official position is that companies with proper documentation should be able to freely conduct business, in practice, companies have reported challenges and delays in obtaining approvals for foreign currency transactions by sub-national regulatory branches. PRC authorities instituted strict capital control measures in 2016, when China recorded a surge in capital flight. China has since announced that it would gradually reduce those controls, but market analysts expect they would be re-imposed if capital outflows accelerate again. PRC foreign exchange rules cap the maximum amount of RMB individuals are allowed to convert into other currencies at approximately USD 50,000 each year and restrict them from directly transferring RMB abroad without prior approval from the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE). SAFE has not reduced the USD 50,000 quota, but during periods of higher-than-normal capital outflows, banks are reportedly instructed by SAFE to increase scrutiny over individuals’ requests for foreign currency and to require additional paperwork clarifying the intended use of the funds, with the intent of slowing capital outflows. China’s exchange rate regime is managed within a band that allows the currency to rise or fall by two percent per day from the “reference rate” set each morning.

Remittance Policies

According to China’s FIL, as of January 1, 2020, funds associated with any forms of investment, including profits, capital gains, returns from asset disposal, IPR loyalties, compensation, and liquidation proceeds, may be freely converted into any world currency for remittance. As noted above, U.S. stakeholders occasionally report challenges obtaining approvals to remit funds, typically in times of significant capital outflows. Based on the “2020 Guidance for Foreign Exchange Business under the Current Account” released by SAFE in August, firms do not need any supportive documents or proof that it is under USD 50,000. For remittances over USD 50,000, firms need to submit supportive documents and taxation records. Under Chinese law, FIEs do not need pre-approval to open foreign exchange accounts and are allowed to retain income as foreign exchange or convert it into RMB without quota requirements. The remittance of profits and dividends by FIEs is not subject to time limitations, but FIEs need to submit a series of documents to designated banks for review and approval. The review period is not fixed and is frequently completed within one or two working days of the submission of complete documents. For remittance of interest and principal on private foreign debt, firms must submit an application, a foreign debt agreement, and the notice on repayment of the principal and interest. Banks will then check if the repayment volume is within the repayable principal. There are no specific rules on the remittance of royalties and management fees. Based on guidance for remittance of royalties and management fees, firms shall submit relevant contracts and invoice. In October 2020, SAFE cut the reserve requirement for foreign currency transactions from 20 percent to zero, reducing the cost of foreign currency transactions as well as easing Renminbi appreciation pressure. In December 2021, PBOC increased the reserve requirement for foreign currency deposits of financial institutions from seven to nine percent, reducing liquidity in forex market as well as easing RMB appreciation pressure.

Sovereign Wealth Funds

China officially has only one sovereign wealth fund (SWF), the China Investment Corporation (CIC), which was launched in 2007 to help diversify China’s foreign exchange reserves. Overall, information and updates on CIC and other funds that function like SWFs was difficult to procure. CIC is ranked the second largest SWF by total assets by Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute (SWFI). With USD 200 billion in initial registered capital, CIC manages over USD 1.2 trillion in assets as of 2021 and invests on a 10-year time horizon. In 2021, CIC reported that during the 2020 period it increased its information technology-related holdings while cutting holdings of overseas equities and bonds. CIC has two overseas branches, CIC International (Hong Kong) Co., Ltd. and CIC Representative Office in New York. CIC has since evolved into three subsidiaries:

CIC International was established in September 2011 with a mandate to invest in and manage overseas assets. It conducts public market equity and bond investments, hedge fund, real estate, private equity, and minority investments as a financial investor.

CIC Capital was incorporated in January 2015 with a mandate to specialize in making direct investments to enhance CIC’s investments in long-term assets.

Central Huijin makes equity investments in China’s state-owned financial institutions.

China also operates other funds that function in part like sovereign wealth funds, including: China’s National Social Security Fund, with an estimated USD 450 billion in assets in 2021; the China-Africa Development Fund (solely funded by the China Development Bank), with an estimated USD 10 billion in assets (2020); the SAFE Investment Company, with an estimated USD 417.8 billion in assets; and China’s state-owned Silk Road Fund, established in December 2014 with USD 40 billion in assets to foster investment in BRI countries. China’s state-run funds do not report the percentage of assets invested domestically. However, China’s state-run funds follow the voluntary code of good practices known as the Santiago Principles and participate in the IMF-hosted International Working Group on SWFs. While CIC affirms they do not have formal government guidance to invest funds consistent with industrial policies or designated projects, CIC is expected to pursue government objectives.

7. State-Owned Enterprises

China has approximately 150,000 wholly-owned SOEs, of which 50,000 are owned by the central government, and the remainder by local or provincial governments. SOEs account for 30 to 40 percent of total gross domestic product (GDP) and about 20 percent of China’s total employment. Non-financial SOE assets totaled roughly USD 30 trillion. SOEs can be found in all sectors of the economy, from tourism to heavy industries. State funds are spread throughout the economy and the state may also be the majority or controlling shareholder in an ostensibly private enterprise. China’s leading SOEs benefit from preferential government policies aimed at developing bigger and stronger “national champions.” SOEs enjoy preferential access to essential economic inputs (land, hydrocarbons, finance, telecoms, and electricity) and exercise considerable power in markets like steel and minerals. SOEs also have long enjoyed preferential access to credit and the ability to issue publicly traded equity and debt. A comprehensive, published list of all PRC SOEs does not exist.

PRC officials have indicated China intends to utilize OECD guidelines to improve the SOEs independence and professionalism, including relying on Boards of Directors that are free from political influence. However, analysts believe minor reforms will be ineffective if SOE administration and government policy remain intertwined, and PRC officials make minimal progress in primarily changing the regulation and business conduct of SOEs. SOEs continue to hold dominant shares in their respective industries, regardless of whether they are strategic, which may further restrain private investment in the economy. Among central SOEs managed by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), senior management positions are mainly filled by senior party members who report directly to the CCP, and double as the company’s party secretary. SOE executives often outrank regulators in the CCP rank structure, which minimizes the effectiveness of regulators in implementing reforms. While SOEs typically pursue commercial objectives, the lack of management independence and the controlling ownership interest of the state make SOEs de facto arms of the government, subject to government direction and interference. SOEs are rarely the defendant in legal disputes, and when they are, they almost always prevail. U.S. companies often complain about the lack of transparency and objectivity in commercial disputes with SOEs.

Privatization Program

Since 2013, the PRC government has periodically announced reforms to SOEs that included selling SOE shares to outside investors or a mixed ownership model, in which private companies invest in SOEs and outside managers are hired. The government has tried these approaches to improve SOE management structures, emphasize the use of financial benchmarks, and gradually infuse private capital into some sectors traditionally monopolized by SOEs like energy, finance, and telecommunications. For instance, during an August 25 press conference, State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) officials announced that in the second half of the year central SOE reform would focus on the advanced manufacturing and technology innovation sectors. As part of these efforts, they claimed SASAC would ensure mergers and acquisitions removed redundancies, stabilize industrial supply chains, withdraw from non-competitive businesses, and streamline management structures. In practice, however, reforms have been gradual, as the PRC government has struggled to implement its SOE reform vision and often preferred to utilize a SOE consolidation approach. Recently, Xi and other senior leaders have increasingly focused reform efforts on strengthening the role of the state as an investor or owner of capital, instead of the old SOE model in which the state was more directly involved in managing operations.

SASAC issued a circular on November 20, 2020, directing tighter control over central SOEs overseas properties held by individuals on behalf of SOEs. The circular aims to prevent leakage of SOE assets held by individuals and SOE overseas variable interest entities (VIEs). According to the circular, properties held by individuals should be approved by central SOEs and filed with SASAC.

In Northeast China, privatization efforts at provincial and municipal SEOs remains low, as private capital makes cautious decisions in making investment to local debt-ridden and inefficient SOEs. On the other hand, local SOEs prefer to pursue mergers and acquisitions with central SOEs to avoid being accused of losing state assets. There is no available information on whether foreign investors could participate in privatization programs.

8. Responsible Business Conduct (RBC)

Additional Resources

Department of State

Department of the Treasury

Department of Labor

Climate Issues

The PRC adopted a national climate strategy in 2021, known as the “1+N” package of climate policies, which provides a roadmap to peak carbon emissions before 2030 and reach carbon neutrality before 2060, in fulfillment of the pledges announced by President Xi Jinping in September 2020. The PRC government has not clarified officially whether the 2060 target applies to all greenhouse gases (GHGs) and all sources, or just to carbon dioxide (CO2) from fossil fuels. The main policies in this “1+N” framework include the Working Guidance for Carbon Dioxide Peaking and Carbon Neutrality in Full and Faithful Implementation of the New Development Philosophy published jointly by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the State Council on October 24 and the Action Plan for Carbon Dioxide Peaking before 2030 released by the State Council on October 26. The Working Guidance is the central “1” plan, while the Action Plan for Carbon Dioxide Peaking is the first “N” document in a collection of plans for important regions and sectors. Additional “N” plans issued as of February 2022 include those for the green industry, public institutions, digital infrastructure, green consumption, state-owned enterprises, and low-carbon energy.

China does not have a national system for natural capital accounting. Some pilot programs exist at the subnational level. For instance, a few local governments in Zhejiang Province began piloting statistical accounts for the value of natural capital starting in 2018. Zhejiang has also piloted the development of an indicator for a “gross ecological product” indicator, which would measure the economic value of ecosystem services. The creation of a “green” GDP indicator that would include measures of biodiversity and/or ecosystem health has been discussed for decades among PRC academics and in policy circles. The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and former State Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) in 2006 published official statistics for China’s green GDP in 2004, but the report was discontinued.

Specific timelines and emissions levels for CO2 peaking by the private sector, different industries, and local governments have not yet been published. Some major SOEs and private companies have voluntarily announced their own carbon peaking or carbon neutrality pledges. For instance, China Baowu Steel Group announced plans to peak its CO2 emissions by 2023, and the tech giant Tencent set a goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2030.

There are numerous central government-level regulatory incentives aimed at various environmental goals. For example, since 2006, the central government has offered subsidies to promote the expansion of renewable power. Subsidies cover the split between renewable energy tariffs (up to a certain level) and the local on-grid price for coal-fired power. Generators may receive subsidies for up to 20 years. As the costs of wind and solar power have fallen, so have subsidy amounts. By February 2021, national-level subsidies for utility-scale solar PV were only around RMB 33 (USD 4.7) per megawatt hour (MWh) on average. Subsidies were phased out for new utility-scale onshore wind and solar PV projects starting in 2021, and for new offshore wind projects starting in 2022. Additional subsidies for renewable power are provided by provinces, cities, and even urban districts.

To support development of the new energy vehicle (NEV) industry, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) introduced NEV purchase subsidies in 2009, handing more than USD 23 million to manufacturers through 2020 per PRC government sources. These subsidies compensated manufacturers for reducing the retail prices of NEVs, which contacts said were instrumental to making PRC-manufactured NEVs affordable. While the PRC began reducing subsidies in 2018 and planned to phase them out entirely by 2020, the government reversed course and extended some subsidies through at least 2022 to sustain consumer demand. Subsidies remain only for vehicles with ranges of over 300 km and those using experimental hydrogen fuel cell or battery-swapping technologies. PRC authorities also extended a policy exempting NEVs from the 10 percent motor vehicle purchase tax through the end of 2022, which further lowers the cost to consumers. Subsidies greatly increased demand for NEVs in the PRC market, driving key supply chains to the PRC and cementing lower consumer prices, according to industry analysts.

China’s national carbon market launched trading in July 2021. The first phase of the market covers over 2,162 thermal power generators (coal and gas), with combined annual CO2 emissions of around 4.5 billion tons. Regulators claim the market will expand to include other high-emission industries over the next four to five years.

The MOFCOM, MEE, and the MIIT jointly issued the “Guidelines for Enterprise Green Procurement (Trial)” to guide companies to adopt green procurement guidelines. Enterprises are advised to avoid the “blacklist” of purchased products, including “high pollution, high environmental risk” products listed in the “Comprehensive Directory of Environmental Protection” formulated by the Ministry of Environmental Protection. According to various estimates, government procurement of “green” products in 2020 reached USD 12.7 billion.

The Ministry of Finance (MOF) and the MEE have released 22 government lists listing environmental labeling products and one list of environmental labeling government procurement items. The products have grown from 856 products in the first issue to one million, and from 14 original product categories to more than 90 categories in 2020. China Environmental Labelling signifies that the product is not only is high-quality but also meets specific environmental requirements covering the entire cycle from production, usage, to disposal.

China ranked 25th on the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation’s (ITIF) Global Energy Innovation Index for 2021, an improvement from 2016. On the MIT Technology Review’s Green Future Index tracking progress towards a low-carbon future, China ranked 45th.

9. Corruption

Since 2012, China has undergone a large-scale anti-corruption campaign, with investigations reaching into all sectors of the government, military, and economy. CCP General Secretary Xi labeled endemic corruption an “existential threat” to the very survival of the Party. In 2018, the CCP restructured its Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) to become a state organ, calling the new body the National Supervisory Commission-Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (NSC-CCDI). The NSC-CCDI wields the power to investigate any public official. From 2012 to 2021, the NSC-CCDI claimed it investigated roughly four million cases. In the first three quarters of 2021, the NSC-CCDI investigated 470,000 cases and disciplined 414,000 individuals, of whom 22 were at or above the provincial or ministerial level. Since 2014, the PRC’s overseas fugitive-hunting campaign, called “Operation Skynet,” has led to the capture of more than 9,500 fugitives suspected of corruption who were living in other countries, including over 2,200 CCP members and government employees. In most cases, the PRC did not notify host countries of these operations. In 2021, the government reported apprehending 1,273 alleged fugitives and recovering approximately USD 2.64 billion through this program.

In March 2021, the CCP Amendment 11 to the Criminal Law, which increased the maximum punishment for acts of corruption committed by private entities to life imprisonment, from the previous maximum of 15-year imprisonment, took effect. In June 2020 the CCP passed a law on Administrative Discipline for Public Officials, continuing efforts to strengthen supervision over individuals working in the public sector. The law enumerates targeted illicit activities such as bribery and misuse of public funds or assets for personal gain. Anecdotal information suggests anti-corruption measures are applied inconsistently and discretionarily. For example, to fight commercial corruption in the medical sector, the health authorities issued “blacklists” of firms and agents involved in commercial bribery, including several foreign companies. While central government leadership has welcomed increased public participation in reporting suspected corruption at lower levels, direct criticism of central leadership or policies remains off-limits and is seen as an existential threat to China’s political and social stability. China ratified the United Nations Convention against Corruption in 2005 and participates in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and OECD anti-corruption initiatives. China has not signed the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery, although PRC officials have expressed interest in participating in the OECD Working Group on Bribery as an observer. Corruption Investigations are led by government entities, and civil society has a limited scope in investigating corruption beyond reporting suspected corruption to central authorities.