U.S. Tariff Policy: Overview, IN FOCUS(IF11030), CRS, Feb. 28, 2023.

Christopher A. Casey, Analyst in International Trade and

Finance

Introduction

A tariff is a customs duty levied on imported and exported

goods and services. Historically, countries used tariffs as a

primary means of collecting revenue. Today, other taxes

account for most government revenue in developed

countries. Tariffs are now typically used to protect domestic

industries or as leverage in trade negotiations and disputes.

The U.S. Constitution empowers Congress to set tariffs, a

power that Congress has partially delegated to the

President. The United States is also a member of the World

Trade Organization (WTO) and a party to a number of trade

agreements, which include specific tariff-related

commitments. Congress and the President thus create U.S.

tariff policy within the context of a rules-based global

trading system.

Rules-Based Global Trading System

The rules-based global trading system was established

following World War II. It began as the General Agreement

on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which was later integrated

into a larger set of agreements establishing the WTO. This

system has aimed to reduce trade barriers and prevent trade

wars by establishing rules for the use of tariff and nontariff

barriers to trade. Among this system’s core rules with

regard to tariffs are

Nondiscrimination. Under the most-favored nation

(MFN) rule, a country must extend any trade

concession, such as a reduced tariff rate, granted to one

country member to all other WTO members. There are

exceptions, such as preferential rates for FTAs, special

treatment for developing countries, and WTO-allowed

responses to unfair trading practices.Binding Commitments. Through multilateral

negotiations, countries bind themselves to ceilings on

tariff rates for specific imports. That ceiling is called the

bound rate, which can be higher than actual applied

rates. Lowering bound rates has been a general goal of

each of the multilateral negotiations.Transparency. The WTO requires members to publish

and report their tariff rates and other trade regulations.Safety Valves. The WTO agreements permit members

to raise tariffs to address unfair trade practices and to

allow domestic industries to adjust to sudden surges in

imports in some circumstances.

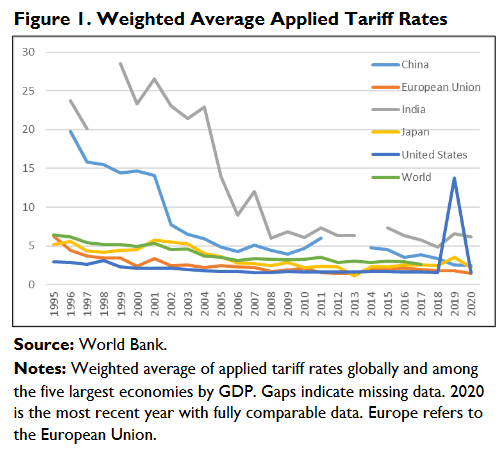

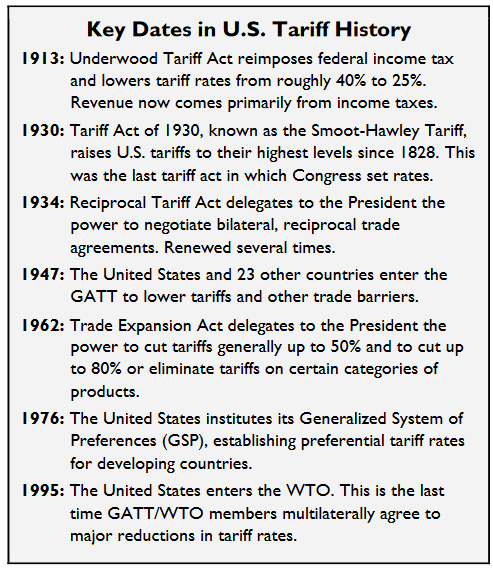

Following the establishment of the GATT in 1947 and the

WTO in 1995, global tariff rates declined significantly,

spurring trade and opening markets for U.S. exports. Since

the establishment of the WTO, the value of exports of U.S.

goods have increased more than 160% adjusted for

inflation.

U.S. Tariff Policy

Who Makes U.S. Tariff Policy?

The Constitution grants the power to lay and collect duties

and to regulate commerce with foreign nations to Congress.

The Constitution grants the authority to negotiate

international agreements to the President. Since tariffs are

no longer a primary source of revenue, they have

increasingly become an instrument of U.S. international

trade and foreign policy. As such, Congress now works

with the President to set tariff policy by granting authority

to negotiate trade agreements and to adjust tariffs in certain

other circumstances.

Presidential Trade Promotion Authority (TPA).

Prior to the 1930s, Congress usually set tariff rates itself. As U.S.

and global tariff rates increased during the Great

Depression, U.S. exports decreased. Congress responded by

authorizing the President to negotiate reciprocal trade

agreements that reduced tariffs through proclamation

authority up to a pre-set boundary. Hence, such an

agreement could enter into force without further

implementing legislation. However, nontariff barriers to

trade (such as discriminatory technical standards) became a

greater focus of trade negotiations in the late 1960s. As a

result, it became difficult to predict the substance of the

negotiations and authorize changes to existing U.S. laws by

proclamation before the negotiations took place. Congress

addressed this challenge in 1974 by establishing expedited

procedures to implement more complicated future trade

agreements. Under these procedures, currently known as

Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), Congress establishes

U.S. trade negotiating objectives as well as consultation and

notification requirements. If the President satisfies these objectives

and requirements, implementing legislation for an agreement

may receive expedited treatment including an

“up or down vote” without amendment. The most recent

TPA, the Bipartisan Comprehensive Trade Priorities and

Accountability Act of 2015, expired in the summer of 2021.

Presidential Discretionary Authority over Tariff Rates.

In dozens of statutes, Congress has empowered the

President to adjust tariff rates in response to specific trade-

related concerns that touch on issues of executive interest,

such as foreign policy and national security, or require an

administrative finding by a U.S. agency. For example,

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 empowers

the President to adjust tariffs on imports that threaten to

impair U.S. national security. Section 5(b) of the Trading

with the Enemy Act and Section 203 of the International

Emergency Economic Powers Act empower the President

in a time of war or emergency to impose tariffs on all

imports. Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974 empowers

the President to raise tariff rates temporarily when the U.S.

International Trade Commission (ITC) determines that a

sudden import surge has caused or threatened serious injury

to a U.S. industry. Congress has also empowered U.S.

agencies to impose duties to offset injurious unfair trade

practices, based on industry petitions or through initiation

by the Commerce Department.

How Is U.S. Tariff Policy Administered?

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) administers the

collection of tariffs at U.S. ports of entry according to rules

and regulations prescribed by the Secretary of the Treasury.

When a good enters a U.S. port of entry, merchandise is

classified and tariffs are assessed using the U.S.

Harmonized Tariff Schedule (USHTS), a compendium of

tariff rates based on a globally standardized nomenclature.

Today, importers self-classify and declare the value or

quantity of their goods. CBP reviews the paperwork,

performs occasional audits, and then collects any applicable

tariffs or penalties as well as any administrative fees.

Finally, CBP deposits any revenue from tariffs or other

penalties into the General Fund of the United States.

What Has U.S. Tariff Policy Been?

Over the past 70 years, tariffs have never accounted for

much more than 2% of total federal revenue. In FY2020,

for example, CBP collected $74.4 billion in tariffs,

accounting for approximately 2.2% of total federal revenue.

Instead, the United States has generally used its tariff policy

to encourage global trade liberalization and pursue broader

foreign policy goals.

Since 1934, the United States has generally reduced or

eliminated many tariffs as part of bilateral and multilateral

trade agreements. By supporting the creation of the GATT

and the WTO, the United States sought to reduce tariff rates

globally within a rules-based trading system. Roughly 70%

of all products enter the United States duty free.

U.S. reductions in tariff rates have not always inspired

others to follow. During the most recent (Doha) round of

WTO trade negotiations, the United States unsuccessfully

attempted to convince advanced emerging economies, such

as China, India, and Brazil, to commit to lower their bound

tariff rates, which they declined to do. This dispute was

arguably one of the reasons that the Doha round of

negotiations was unable to produce an agreement.

Low U.S. tariff rates have also served as an instrument to

achieve other foreign policy goals. For example, to

encourage global economic development, Congress created

the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), which

authorizes the President to give unilateral duty-free

treatment to some products from some developing

countries. The United States has also pursued FTAs as part

of broader foreign policy and security goals.

Issues for Congress

For more than 80 years, Congress has delegated extensive

tariff-setting authority to the President. This delegation

insulated Congress from domestic pressures and led to an

overall decline in global tariff rates. However, it has meant

that the U.S. pursuit of a low-tariff, rules-based global

trading system has been the product of executive discretion.

While Congress has set negotiating goals, it has relied on

Presidential leadership to achieve those goals.

The Trump Administration was openly critical of low-tariff

policies and made extensive use of the authorities delegated

to the President to increase tariffs on certain goods. As a

result, the amount of duties paid on U.S. imports doubled

from FY2015 to FY2020 from approximately $37 billion to

$74 billion. The Biden Administration has maintained some

of those policies. Congress may want to consider whether

the current restrictions on such delegated authorities

adequately protect congressional interests and reflect

congressional prioritie

https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/IF11030.pdf