Inheriting Traditions, Resembling Oneself and Making Stories: A Conversation on Ornaments and Originality with Kengō Takiguchi (woodcarver) and Yūto Arakaki (Shisa maker)

A wooden carving of a bear with a salmon in its mouth sitting on top of a television. The Shisa guardian lions that are always placed to ward off bad luck in Okinawan homes. Though they are made using different techniques, woodcarving and pottery respectively, both of these objects are intended to be put on display. In this article, we hear from two artisans working in different media to uncover how these 'original ornaments' are made.

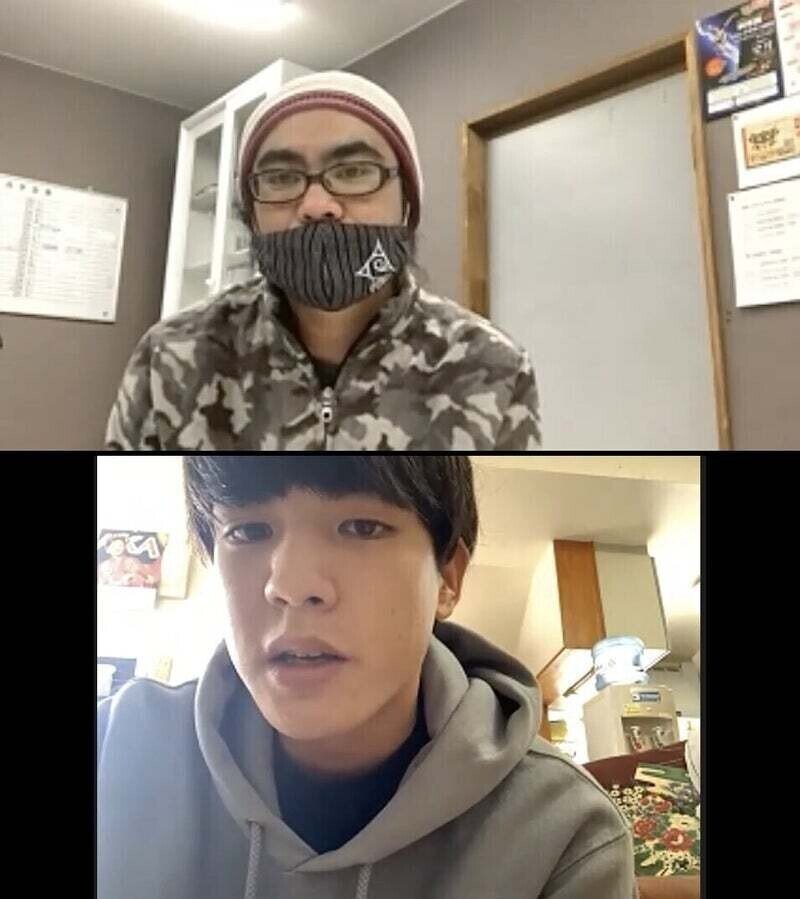

Above: Kengō Takiguchi (woodcarver). Born in 1982 in Akanko Onsen, Hokkaido, Kengō is the eldest son of master woodcarver Masamitsu Takiguchi. After studying abroad in Australia, he returned to Japan where he worked both as a woodcarver and in the dairy industry. Following his father's death last year, Takiguchi took over his workshop-cum-giftshop 'Ichinge no Mise'. A member of the AKAN AINU ARTS & CRAFTS -> NEXT project, he created 'Iwan Sumari (six foxes)' with Sapporo-based speciality store FAbULOUS.

Below: Yūto Arakaki (Shisa artist). Born in Yomitan, Okinawa Prefecture in 1994 to a family of ceramic artists (known in the Okinawan language as a Yachimun family) who have been making Shisa statues and ceramic vessels for generations. After graduating from university, Arakaki became a Shisa artist. He incorporates the feeling of 'making this statue's owner happy' into the manufacturing of each and every piece.

Let me begin by asking you to introduce yourselves.

Takiguchi (T): I am Kengō Takiguchi from Akanko Onsen. I operate a shop in a hamlet known as the Akanko Ainu Kotan (settlement) , where I make woodcrafted objects and sell them in my shop. I started cariving when I was about 20. Now I'm 38. Along the way I took some time out to work in the dairy industry elsewhere in Hokkaido but after my father passed away in 2017 I returned to take over his shop.

Aragaki (A): I am Yūto Arakaki and I am 26 years old. I make ceramic Shisa statues in Yomitan, Okinawa. My family has been making Shisa since my great-grandfather's generation and I am carrying on the tradition. I started when I was a third-year university student. In the beginning I went to university to study social welfare and I wasn't interested in making Shisa. However, when I saw the large dragon statue that my father made for Kiyomizu-dera Temple in Kyoto, I was very impressed. That is when I started making Shisa.

You both come from families of makers. Did you always have a sense of woodcarvings and Shisa respectively as familiar objects?

T: Yes, I did. I saw my father travel to many different places to harvest timber and bring it home. Furthermore, in the Ainu kotan (settlement), it wasn't only my father but lots of people who were whittling away with their chisels. It was a very familiar sight.

A: It's the same for me. Also, Shisa are such an indispensible item in daily life in Okainwa, more so than even your readers probably realise. Just as you wouldn't build a house without a toilet, it is imposslbe to think of a house without a Shisa statue (laughs).

▲Shisa statues by Arakaki. He has received many orders for his statues from abroad.

When was it decided that you would inherit your crafts from your fathers?

T: In the old days, an Ainu male was only considered a grown man when he had learned how to carve. It was just accepted that he would make items for everyday use such as dishes and trays and he even made things like ritual objects. They sold these as souveniers in tourist sites. It wasn't like my father said to me that he wanted me to take over from him as a woodcarver. At one time, I left home and started on the road to becoming a dariy farmer. But even then I made little carvings after I finished work. It wasn't so much that I made a big decision to take over from him as much as that I just carve because I enjoy it.

A: In our family, too, the attitude was 'just do something you enjoy'. As I said earlier, it was really the impact of seeing my father's piece [at Kiyomizu-dera] that made me think about making Shisa statues myself.

Have both of you been heavily influenced by your fathers' work?

T: I think my carving technique is inferior to that of my father. Actually, at the time when I worked with my father in the shop, it was his pieces that jumped off the shelf. Having said that, its not like I have been chasing after him. I just try and make things that I like. For example, I make carved wooden butter knives and other objects. I experiment with using different shapes and materials.

▲Takiguchi's butter knives featuring Ainu designs on the handles.

A: For me, my father's work got me started and it continues to have a big influence on me. No matter how hard I try to copy him, even when I make the same object, the things we have seen and done come together to make completley different works.

The purpose of a Shisa statue is to keep away frightening things so I think it is important that they be frigthening. For me, my father's Shisa are the most terrifying (laughs). I am always trying different things to try and figure out how to outmatch him.

The thing is Shisa lions are not real are they? So while I basically follow his example, I try and insert the kind of 'animal-like' qualities that appeal to me. I also try and include scary faces, devils, even images of [the Buddhist saint] Bodhidharma.

Kengō, I feel that you are searching for a different path from that of your father.

T: I know it might sound like I am selling myself short but I never thought that I could out compete with my father's work. He was carving table-sized reliefs from the time he was litte. I don't think it is possible to match someone like that.

Nevetheless, in my carving practice I adjust materials and shapes to try and create something new. The butter knives I made when I first started were so bad that I couldn't show them to anyone. But gradually, I began to understand how to use my materials. Recently, I made a special order of some ebony because I want to try working with a hard material.

I recall that my father, too, sometimes used horn from the Hokkaido sika deer. Although we refer to our craft simply as woodcarving, we don't only carve wood. I am also challenging myself to try new things, such as earrings made from whale's teeth and coral necklaces.

The idea of using new materials is interesting. I wonder whether the two of you, Takiguchi as a woodcarver and Arakaki as a ceramic artist, use a different approach to your materials. A carver shapes the piece by whittling away at a piece of wood while a ceramic artist shapes their work directly out of the clay that then becomes the finished piece. Arakaki, have you experimented with new materials?

A: Actually, my father sometimes used clay from other places, like Shigaraki. He wasn't fastidioius aobut using Okinawan clay. However, I plan only to use clay from Okinawa. The way I see it, Shisa are Okinawan objects and I want to emphasise that.

In terms of other materials, I am getting to grips with different glazes that my father never used. I had a memorable failure when I wondered whether I could colour the glaze by dissolving goat dung, which is plentiful in Okinawa (laughs). I would like to produce my own original colours that haven't been used by my forebears.

▲'Iwan Sumari (6 foxes)', made by Takiguchi for AKAN AINUE ARTS & CRAFTS → NEXT (Photo: Manabe Yuri)

What does 'original' mean in traditional crafts such as woodcarving or Shisa making? I have the sense that if you make too many innovations, then your work would not be recognised as a carving or Shisa.

T: You know those Hokkaido carvings of an a bear with a fish in its mouth? They are extremely popular at the moment. I think people feel nostalgic about an object that used to be found everywhere. I do think that these kinds of booms exist in the psychology of our customers.

However, I do not spend much time thinking about big questions like what is 'woodcarving'? But when I look at the waste shavings from my carvings, sometimes its like new shapes do come to me. When I look at the form of a deer's horn, for example, I feel like I want to carve a different motif from the one I made yesterday. I think, maybe I should try something different today? Alright, what should I make then? That's the general idea.

A: I think about originality after I've finished a piece and I start analysing for myself where I went wrong and where I got it right. Then I try and apply those insights to my next piece. If I do that, then sure enough I find I am making work which has my own original stamp. I think that if I make small changes each time I produce one then the work take on my character.

Actually, it is said that Shisa resemble their maker. The Shisa my father makes do look a little like him and my grandfather and grandmother's Shisa in particular do look like them. I think that what I make will inevitably start to look like me.

Finally I would like to ask about the the Iwan Sumari (6 foxes) Kengō made as part of the current project.

T: Originally, I had the idea for an ornamental fox 'who can make your wish come true'. While I was playing around with making it I started to think, wouldn't it be interesting if I it could be split into 6. The number 6 has a special meaning for Ainu people. It is the best number and also means 'many'.

When you tie the six foxes together into one with string, they grant the wish that they heard while they were open and on display. Its like the 6 foxes are consulting with one another. Then when your wish comes true, you can open them up and line the foxes up again. Actually, I am planning to sell them with one of the six faces uncarved. When the customer sends it back to my studio after their wish has been fulfilled, I will complete the carving.

A: That's fascinating! As I explained earlier, Shisa are meant to ward off back luck. Apparently, this idea can be traced back to the Egyptian Sphinx. In mainland Japan, this tradition took the form of the Komainu guaridan lion-dogs at Shinto shrines. In Okinawa, we have the Shisa. They are not just ornaments. They have both a meaning and a function.

T: Among the Ainu, we believe that the owl is the guardian god of the village and owls are often the subject of woodcarvings. But in fact, we have no Ainu no tradition of foxes granting wishes. I may as well have made a carving of a mouse. But I thought, maybe something new might emerge even from a story I made up by myself.

▲The string used to tie the six fox statues together is also made using Ainu craft techniques. (Photo: Manabe Yuri)

Today more than ever, when it seems common sense to value efficiency above all else, it is essential that we make room for 'play' within our living environment. Yūto Arakaki in Okinawa, who is revitalising the much-loved Shisa and Kengō Takiguchi in Hokkaido, who pursues new forms in woodcarving raise ideas that can once again teach us the value of 'ornaments', whose reason for existence comes from the human imagination and of their originality.

Translation: Alexander Brown

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?