Taking Root, Living and Connecting: A Conversation on Tools and Folklore with Hiroyuki Shimokura (Jeweller) and Keiichi Asakura (Yawaiya)

Engravings of patterns within a folkloric tradition and a folk art that rediscovers the value of tools within daily life. How do we approach the transmission of cultures that people have cultivated throughout history. In this conversation with two people who deal in art objects rooted in local lifeways, we think about what folklore might look like in the future.

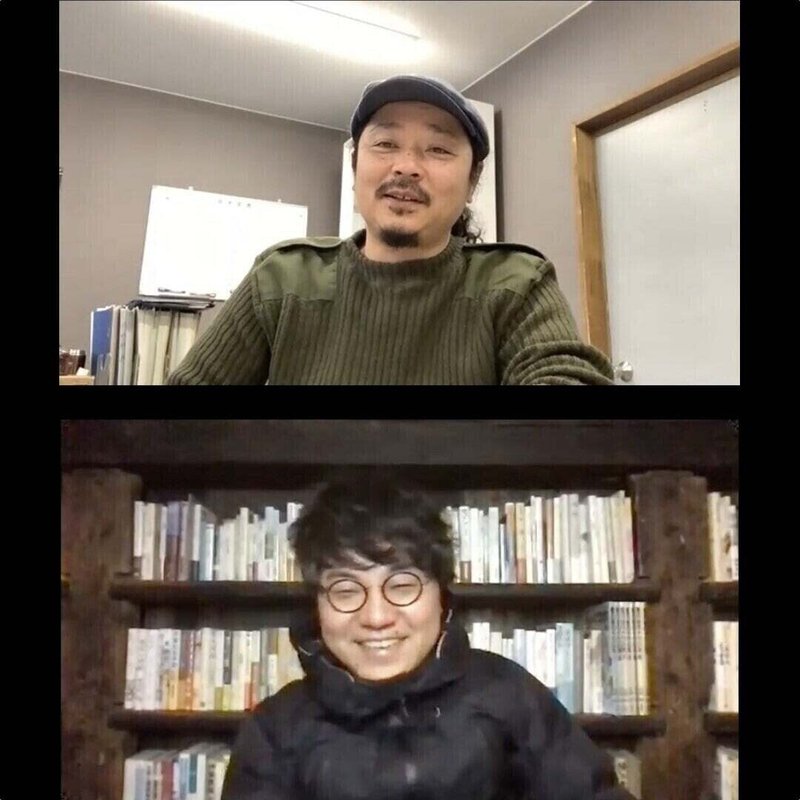

Right: Hiroyuki Shimokura (jeweler). Born in 1975, Shimokura began engraving when he was 20 years old. After encountering Ainu traditional clothing, he was deeply impacted by its strange and wonderful designs and began making Ainu-influenced accessories. In 1999 he launched his own brand, Ague. In 2013 he moved to Akanko Onsen and in 2019 opened his studio, café & gallery KARIP. He is married to handicrafter Emi Shimokura.

Left: Keiichi Asakura (Yawaiya). Born in Takayama in Gifu Prefecture, Asakura is the owner of the shop Yawaiya. After working outside Gifu for a time, he returned to Takayama. In 2016 he opened Yawaiya and in 2017 added Yawaiya Bookshop, a second-hand bookshop in the second-floor loft. In 2020 he remodelled the bookshop and opened a private reading room where he has made his collection of humanities books available to the public.

May I start by asking you both to introduce yourselves?

Hiroyuki Shimokura (S): The Great East Japan Earthquake Disaster gave me the excuse to move to Akanko. I had visited Hokkaido regularly since I was a teenager and always thought it would be great to live somewhere like that. But my work and my friends were in Tokyo, so it was hard to make the move. Then 2011 happened and we decided to just do it. So long as we stayed in Tokyo it seemed like the chance would pass us by, so we took the plunge to do something we had always wanted to do.

Now I am renting a workshop where I make and sell my work. There are lots of artists around here whom I admire so I’ve also been buying their work and putting it on display. We also run a coffee shop where we roast our own beans, which is also something of a hobby.

Keiichi Asakura (A): I currently run a shop in the tourist town of Hida Takayama in Gifu Prefecture called Yawaiya that carries old books and folk arts. I played music all through my 20s but I couldn’t make a living at it and so I returned to my hometown, got a job and worked in a ramen noodle shop.

Actually, it was also the impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake Disaster that led me to open a shop. I was driven by the idea that I needed to create something with my own hands. Initially I studied farming and other things. But in the end, I took the path of curating things other people make: old books and folk arts. Even so, without those earlier experiences I wouldn’t have the shop I am running now.

▲Asakura’s shop Yawaiya carries household items like tableware and lamps as well as second-hand books.

Mr Asakura, I heard that you created your shop by dismantling and moving a 150-year-old Japanese-style house. Was that out of love for things with a history?

A: People often misunderstand that. It’s not that I love old Japanese houses. Its more accurate to say that in order to properly understand the way of life in my hometown, I wanted to replace the box-style house with one that was suited to the local environment. Of course, I really treasure Hida Takayama’s culture and I am studying to learn more about it. But it’s not like I live a ‘conscientious life’. I go to the convenience store to buy a coffee just like everybody else (laughs).

S: I know how you feel. I have no intention of being all stoical and working too hard. Since my first encounter with jewellery making, the more I do the more engrossed in it I become. You might say that the more progress I’ve made, the more I can see of the depths that lie just on the other side. I just like to throw myself into things, you know. My close friends say that I’m addicted to being super focussed.

Mr Shimokura, I heard that when you came into contact with Takeki Fujito’s work in the Akanko area, you were really impressed.

S:It all started when I was working on the prototype for my Bear Ring. A friend of mine who had seen the ring told me about a shop called Kumanoya. The shop is run by the artist Takeki Fujito, who makes wooden carvings of bears. I was blown away by the work I saw in his gallery and I just stood stock-still for ages. When I think back on it now, it’s a bit embarrassing really but at the time I issued Fujito with a challenge. I said ‘One day I’m going to make something even better than this’. It felt like I had been shown something was far beyond the bear rings I had been making.

So, I went home and started working on my pieces again from scratch. It became a bit of an annual ritual to work for a year, go to Akanko in the summer and then return home disappointed. Interestingly, there would be things I couldn’t’ see the year before that I could now see. Then the next year something else would become visible that I had missed the previous year. In the end, I felt even more strongly that it would be no easy task to surpass him. Of course, I am still working on trying to exceed Fujito’s work, but I feel like I haven’t even come close to catching up with him.

▲Shimokura’s ‘Bear Ring’. It was developed it in his own style through his encounter with Ainu culture.

The folk arts you stock at Yawaiya are known through a movement to recognise the things we use in everyday life as art.

A: I have some sympathy with where Mr Shimokura is coming from. My shop is in a tourist area, so a lot of my customers are visitors from outside the prefecture. But Yawaiya is not in the center of town and I don’t have a sign, so unless you are planning to visit, you won’t end up there. That’s why I try and get local people who have roots in the area to buy from me. I want locals to buy my products as gifts too, rather than seeing them as luxury goods that are just for people with a love of folk art. I think that the artworks themselves are happier when they are tools, when they get to be used in people’s daily lives.

What is the difference between a tool that is an artwork and tool that is just a tool?

A: Well, I think that tableware can be nurtured by being used every day. It’s like the way denim develops character when you wear it. For example, a bowl you buy at the 100 yen shop and one you might buy from my shop for 3,000 to 4,000 yen are functionally the same. Indeed, the cheaper one might be less likely to break. But an artwork is something that becomes an antique through being used. When you make the effort to handle something with great care, it can produce love. I think that’s really significant.

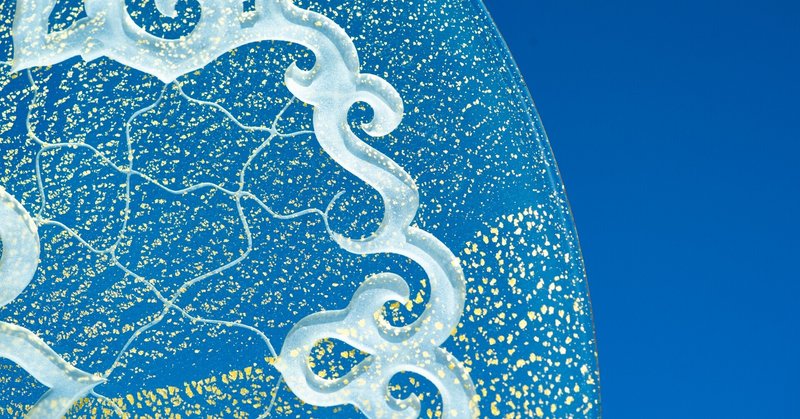

▲Shimokura’s ‘Blown Glass Display Plate with Ainu Pattern’. He makes two versions, one has gold leaf inserted into the glass (above right) and the other is completely transparent (below left).

Mr Shimokura, can I ask you about the ‘Blown Glass Display Plate with Ainu Design’ that you made for this project?

S: This glass plate is intended for display. Other dishes will be placed on top of it, so it is not a utilitarian object but rather a ‘plate meant for show’. I wanted to make a piece that was engraved on both sides and I have realised that idea here. But it’s not just for displaying on a tabletop. Other uses come to mind, like inserting it in the round window of a door. So I made two types, one with gold leaf and one without. I like the way you can make something very similar using the same pattern that conjures up completely different images of how to use it.

Inside that sense of translucence, the Ainu patterns have a presence don’t they? When you are striving for originality in your work, how conscious are you of the history of these Ainu patterns?

S: At the moment, I am not thinking about it that much. Ainu patterns are not fixed. Its more like I start free drawing and then it connects connects with these patterns. Actually, back in the day I was much more earnest than I am today. I used to feel strongly that I must draw Ainu patterns. But as I have gotten older, I have loosened up and now I don’t feel so compelled to draw them.

But that isn’t to say that Ainu motifs are just another pattern. I think they have a magical dimension. We once had an exhibition of work by three generations. It brought together work by our grandparents’ generation, their children and their grandchildren’s generation, like me. The patterns in that exhibition were all different. But somehow, they had the same smell. Maybe that’s tradition, no, I mean folklore. Even if they make different work, the same family really does share something like a smell.

A: I also really cherish this idea of folklore rather than tradition. The Japanese word for tradition is made up of two Chinese characters that mean ‘legend’ and ‘control’ respectively. You need both to maintain a tradition. It requires an immense effort to transmit history and consolidate cultural forms. You also need a language through which to present yourselves to the outside. The implication is that you need to really emphasise your identity.

On the other hand, the word folklore means something more like ‘to communicate and receive’. Its more passive you see. When you ‘receive’ something that has been communicated to you, it’s like it becomes a part of you. I want to face look at history without having to put on a big front. If you do your best to communicate the blessings you have received to the next generation, I think that’s about right.

▲The Ainu patterns carved into the glass through sandblasting exhibit a new sense of presence on top of the clear glass (Photo: Yuri Manabe).

Shimokura, who touched on his own style of ‘enjoyment’ and Asakura, who shows us the value of the tools that acquire layers of history through daily life. Both place great weight on pure enjoyment through words that overflow with casual charm. As we face a new era in the 2020s, perhaps the passive approach of folklore will take on even greater significance.

Translation: Alexander Brown

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?