(112)Section 5: The Rise and Fall of Polytheistic Civilization II

Chapter 1: The Indus

13-1 Suzuki Shosan and the Birth of Japanese Capitalism

Shosan Suzuki is an unusual name. Japanese Buddhist priests are usually known by their single word Buddhist names, monikers they obtained after forsaking their secular title. There is the venerable Dogen and the famous Eisai for example. Shosan Suzuki on the other hand was a Buddhist scholar who spent a good portion of his life as a secular writer and an equally significant portion of his life as an official Buddhist priest, earning him the secular Shosan and the non-secular last name Suzuki.

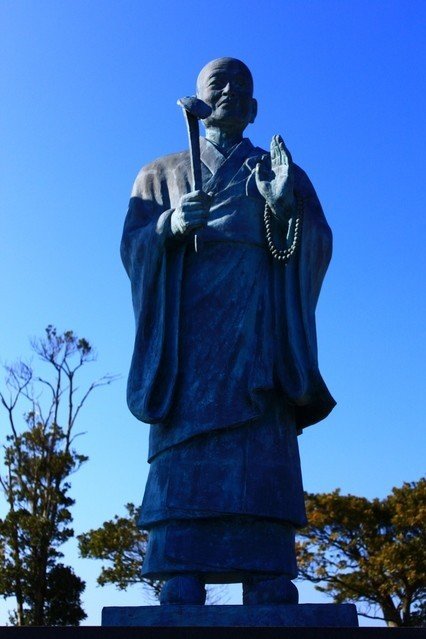

▲ Zen monk Shosan SUZUKI ©タナカ ダイキ

Born to a powerful warrior family in Mikawa Province in 1579 (Tensho 7), Shosan spent the beginning of his life serving under Ieyasu Tokugawa (1542-1616, in office 1603-1605). Shosan was a distinguished warrior and a man of outstanding military achievement, having fought in several decisive battles including the Battle of Sekigahara and the Siege of Osaka. But when the nation was finally visited by peace in 1620 (Genna 6), Shosan made an abrupt change in lifestyle. At the age of forty-two, he renounced his warrior life for the Zen priesthood.

Shosan made his own pilgrimage and traveled the country, eventually ending up in Shimabara, Kyushu, where, after the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637 (Kan’ei 14), he devoted himself to spreading what was then an explosion in anti-Christian sentiment. In his seventy-seven years of life, a long time back then, he had authored several populist treatises, written primarily in the simpler-to-read kana, exemplifying his own unique teachings in his own unique style of Zen.

Renowned Japanese scholar of Buddhist scriptures, Hajime Nakamura, summarizes Shosan’s ideology nicely as he references Shosan’s most recognized work, Banmin tokuyo (Right Action for All):

[Shosan] rejected the ascetic leanings of conventional Buddhism and argued that all occupations functioned as the embodiment of Buddha nature. He taught that devotion to ordinary work and tasks were in and of themselves Buddhist practice, explaining ‘all vocations are Buddhist practice. It is on the basis of man’s work that Buddhahood is to be attained.’

Nakamura affirms that Shosan was the first person in Japan to speak of the idea that the essence of Buddhism could be found in vocational ethics.

If you remember, it was Max Weber who said that the birth of Western capitalism can be traced back to Calvinism. Japanese historian Shichisei Yamamoto believed the father of Japanese capitalism was none other than Shosan Suzuki. In a new release of his seminal work, The Spirit of Japanese Capitalism, Yamamoto references and discusses several of Shosan’s writings, which I’ll dip into shortly.

But first, a little context. Shosan lived at a time when the Chinese philosophy of neo-Confucianism served as the fundamental guidebook for the warrior. Japan’s protracted period of intense military conflict and social unrest known as the Sengoku jidai (Age of Warring States) was marked by rampant corruption, betrayal, and assassinations, and it was Ieyasu Tokugawa, who, having brought the madness to an end, sought to establish a new age of peace and morality with neo-Confucianism.

Neo-Confucianism dictated a strict social hierarchy known as the four occupations (gentry or literati, peasant farmers, artisan and craftsmen, merchants and traders). This is because, in premodern China, only those who had successfully acquired neo-Confucian expertise were considered the select few, the elite, who were qualified to lead the masses. This included not only scholars, but bureaucrats who had passed the civil service examination known as the imperial examination or keju. In other words, the emperor classified people on the basis of their ability to master the ethical philosophy and political science that was neo-Confucianism.

As peace began to take root in Japan, so did neo-Confucianism and the Edo period tendency to assume the ruling class warriors, or the gentry as they were, as citizens deserving of respect in their social standing far above the humble farmer, artisan, and merchant.

The God of Commerce

But Shosan did not fall prey to such elitism and discriminatory thinking. We get a glimpse into his philosophy in the section he calls “the farmers daily guidance”:

A farmer said, ‘I do not neglect that great matter, my rebirth, but I have no time, for work on the farm never lets up. It is a wretched way I have to make my living. This present life of mine is worthless, and suffering will be mine in the future. This distresses me very much. What can I do to attain realization?’

‘Farm work is Buddhist practice,’ I replied. It is misunderstanding that makes it menial work. When your faith is firm, it is the practice of a Bodhisattva. …as you labor so painfully hard in burning heat and freezing cold, with spade, hoe, and sickle, take body and mind, where the passions grow thick, as your enemy. While you hoe and reap, press the attack and press it again upon your mind, as you work. In any period of leisure the passions will grow thicker yet. When you work painfully hard as you assault body and mind, your mind is untroubled. (Royall Tyler, trans. 1977. Selected Writings of Suzuki Shosan [Ithaca: Cornell University East Asia Program])

This, he said, is the practice of Buddhahood. A farmer has no need of a monks practice. He continues:

To receive life as a farmer is to be an officer entrusted by heaven with the nourishment of the world. give your body, therefore, utterly up to heaven, without the least thought for yourself. Work the fields in true service to heaven’s way and celebrate, as you grow the five grains, the Buddhas and the kami. Make a great vow to give to all, yes, even to the very insects, and say Namu Amida Butsu, Namu Amida Butsu in time with the strokes of the hoe. (ibid.)

A merchant then comes to Shosan with the same dilemma; he too has no time to devote to the practice of Buddhahood. Not surprisingly, Shosan has a similar response. All vocations are opportunities for training in the way of the Buddha. Hard work paves the way to Buddhahood. Without merchants, the world would be lost. Without the ruling warriors, our land would be lawless. Without farmers, we would grow hungry. And without merchants, there would be no free circulation of goods.

▲ Japan was a hierarchical society of samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants during the Edo period. ©Skylight / PIXTA(ピクスタ)

In short, he teaches that all trades benefit the world in their own way, and that this is the original Buddha teaching. Through diligence and industriousness, he goes on to add, every person can unleash her and his intrinsic Buddhahood.

Shichihei elaborates on Shosan’s idea of the freedom that merchants bring:

We all use the word freedom in a variety of contexts, often without thinking. but very few people realize that, at a very basic level, not living in a state of inconvenience is largely thanks to the circulation of goods and money. If this type of circulation ever were to come to a stop, everyone would experience restriction on all levels. If the flow of oil or food suppliers were to ever stagnate, all Japanese would soon find themselves completely and utterly stuck. They would probably even lose their ability to discuss freedom. The buying and selling of goods is basic to this idea of commodity circulation. Shosan continues, ‘commerce is the duty heaven has entrusted to those whose role is to promote freedom throughout the nation.’ (Shichihei Yamamoto, [re-release] Yamamoto Shichihei no nihonshihonshugi no seishin [Tokyo: Bijinesusha, 2015])

But there is a definitive difference that separates the warrior from the business man. No matter how successful the warrior is in pursuing the path of the sword, profits and earnings will never grow. Not so, of course, for the merchant. One businessman, however, wasn’t content with merchants making all the money.

Editor/ Noriko Knickerbocker , Aquarius Ltd.

Translator/ Matthew Hunter , Aquarius Ltd.

©Motohiko Izawa 2018-2020 All rights reserved. No reproduction or republication without written permission.

Izawa tackles for the first time the mysteries of the world in a historical journey of intrigue and cross-cultural understanding.