Overdiagnosis in Cancer (Welch, Black 2010)

日本語訳はDeepLにかけたものに読みやすいように改行をくわえています。

Abstract

This article summarizes the phenomenon of cancer overdiagnosis—the diagnosis of a “cancer” that would otherwise not go on to cause symptoms or death. We describe the two prerequisites for cancer overdiagnosis to occur: the existence of a silent disease reservoir and activities leading to its detection (particularly cancer screening). We estimated the magnitude of overdiagnosis from randomized trials: about 25% of mammographically detected breast cancers, 50% of chest x-ray and/or sputum-detected lung cancers, and 60% of prostate-specific antigen–detected prostate cancers. We also review data from observational studies and population-based cancer statistics suggesting overdiagnosis in computed tomography–detected lung cancer, neuroblastoma, thyroid cancer, melanoma, and kidney cancer. To address the problem, patients must be adequately informed of the nature and the magnitude of the trade-off involved with early cancer detection. Equally important, researchers need to work to develop better estimates of the magnitude of overdiagnosis and develop clinical strategies to help minimize it.

DeepL翻訳

本稿では、「がんの過剰診断」(診断されなければ症状や死亡に至らないはずの「がん」が診断される現象)について概説する。

がんの過剰診断が起こるための2つの前提条件、すなわち、沈黙の疾患貯蔵庫の存在とその発見につながる活動(特にがん検診)について述べる。

ランダム化試験から、マンモグラフィーで検出された乳がんの約25%、胸部X線および/または喀痰で検出された肺がんの50%、前立腺特異抗原で検出された前立腺がんの60%という過剰診断の規模を推定している。

また、CT(コンピュータ断層撮影)で発見された肺癌、神経芽腫、甲状腺癌、メラノーマ、腎臓癌の過剰診断を示唆する観察研究および人口ベースの癌統計からのデータも検討する。

この問題に対処するためには、がん早期発見に伴うトレードオフの性質とその大きさについて、患者に十分な情報を提供する必要がある。

同様に重要なことは、研究者が過剰診断の大きさをよりよく推定し、それを最小限に抑えるための臨床戦略を開発することに取り組む必要があることである。

Introduction

Early detection has forced clinicians and researchers to contemplate a more expansive and, to many, counterintuitive definition of the word “cancer.” What most of us were taught in medical school is captured by the terse definition contained in the medical dictionary—“a neoplastic disease the natural course of which is fatal” (1). It was a simple definition that was largely accurate in an era when patients were diagnosed with cancer because they had signs and symptoms of the disease.

But that all changed after we became technologically able to advance the time of diagnosis and detect cancer early—before it produces signs and symptoms. Now it has become evident that the word “cancer” encompasses cellular abnormalities with widely variable natural courses: Some grow extremely rapidly, others do so more slowly, others stop growing completely, and some even regress. Clinicians are left with the realization that the word “cancer” is less a prediction about disease dynamics and more a pathological description made at a single point in time. Continued adherence to the dictionary definition of cancer, however, can lead to harm—including overuse of anticancer therapies.

Although not yet contained in medical dictionaries, recently, a new word has appeared in the medical literature to describe a side effect of our technological progress: “overdiagnosis.” This article is intended to summarize the phenomenon.

早期発見により、臨床医や研究者は「がん」という言葉をより拡大解釈し、多くの人が直感的に理解できるような定義を考えなければならなくなりました。

私たちの多くが医学部で教わったのは、医学辞典に載っている「致命的な自然経過をたどる腫瘍性疾患」という簡潔な定義である(1)。

この単純な定義は、患者にがんの徴候や症状があれば、がんと診断していた時代には、ほぼ正確なものでした。

しかし、診断の時期を早め、がんが兆候や症状を出す前に早期発見することが技術的に可能になったことで、すべてが変わりました。

現在では、一口に「がん」といっても、細胞の異常はさまざまな経過をたどることが分かっています。

あるものは非常に急速に成長し、あるものはゆっくりと成長し、あるものは完全に成長を止め、そしてあるものは退行する。

あるものは極めて急速に増殖し、あるものは緩やかに増殖し、あるものは完全に増殖が止まり、あるものは退縮する。

「がん」という言葉は、疾患の動態を予測するというよりも、ある時点における病態の記述であるという認識が、臨床医の間に定着している。

しかし、辞書的な「がん」の定義に固執し続けると、抗がん剤の過剰投与などの弊害が生じることがある。

医学辞典にはまだ載っていないが、最近、技術の進歩の副作用を表す新しい言葉が医学文献に登場した。"過剰診断 "である。本稿では、この現象を整理することを目的とする。

What is Cancer Overdiagnosis?

Overdiagnosis is the term used when a condition is diagnosed that would otherwise not go on to cause symptoms or death. Cancer overdiagnosis may have of one of two explanations: 1) The cancer never progresses (or, in fact, regresses) or 2) the cancer progresses slowly enough that the patient dies of other causes before the cancer becomes symptomatic. Note that this second explanation incorporates the interaction of three variables: the cancer size at detection, its growth rate, and the patient’s competing risks for mortality. Thus, even a rapidly growing cancer may still represent overdiagnosis if detected when it is very small or in a patient with limited life expectancy. Overdiagnosis should not be confused with false-positive results, that is, a positive test in an individual who is subsequently recognized not to have cancer. By contrast, an overdiagnosed patient has a tumor that fulfills the pathological criteria for cancer.

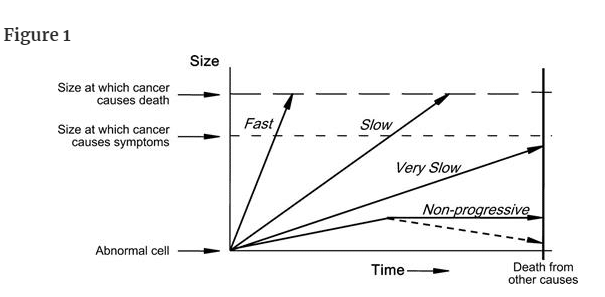

To understand overdiagnosis, one must first understand the heterogeneity of cancer progression, which can be diagrammed using arrows to represent different rates of cancer progression (Figure 1). The arrow labeled “fast” represents a fast-growing cancer, which is defined as one that quickly leads to symptoms and to death. The arrow labeled “slow” represents a slow-growing cancer, which is defined as one that leads to symptoms and death but only after many years. The arrow labeled “very slow” represents a cancer that never causes problems because the patient will die of some other cause before the cancer is large enough to produce symptoms. The most familiar clinical example is likely a small low-grade prostate cancer in an elderly male. The arrow labeled “nonprogressive” represents cellular abnormalities that meet the pathological definition of cancer but never grow to cause symptoms—alternatively, they may grow and then regress. Although the concept of nonprogressive cancers may seem implausible, basic scientists have begun to uncover biological mechanisms that halt the progression of cancer (2–4). Some cancers outgrow their blood supply (and are starved), others may be recognized by the host's immune system or other defense mechanisms (and are successfully contained), and some are simply not that aggressive in the first place.

過剰診断とは、本来であれば症状や死亡に至ることはない病気が診断されることを言います。

がんの過剰診断には、2つの説明があります。

1) がんが進行しない(または、むしろ後退する)、

2) がんの進行が遅いため、がんに症状が出る前に他の原因で患者が死亡する。

この2つ目の説明には、発見時のがんの大きさ、がんの成長速度、患者の死亡リスクという3つの変数の相互作用が含まれていることに注意する必要がある。

したがって、急速に成長する癌であっても、非常に小さいうちに発見されたり、余命いくばくもない患者であれば、過剰診断となる可能性がある。

過剰診断は、偽陽性、すなわち、後にがんでないと判明した人の検査が陽性であったことと混同してはならない。これに対して、過剰診断された患者は、がんの病理学的基準を満たす腫瘍を有している。

過剰診断を理解するためには、まず、がんの進行の不均一性を理解する必要があります。

この不均一性は、矢印を使ってがんの進行速度の違いを表すことで図式化できます(図1)。図1)。

「FAST」と書かれた矢印は、進行の速いがんを表し、すぐに症状が出て死に至るがんと定義される。

一方、「SLOW」と書かれた矢印は、進行が遅いがんを表し、症状が出て死亡するまでには何年もかかるがんであると定義されています。

「VERY SLOW」という矢印は、症状が出るほど大きくなる前に他の原因で死亡するため、問題を起こすことのないがんを表しています。

最も身近な臨床例としては、高齢の男性にできた小さな低悪性度の前立腺がんが考えられます。

「Non-progressive」と書かれた矢印は、病理学的ながんの定義には合致するが、症状が出るほどには成長しない細胞異常である。

非進行性がんという概念はありえないように思われるかもしれませんが、基礎科学者たちは、がんの進行を止める生物学的メカニズムを明らかにし始めています(2-4)。

ある種のがんは血液供給が追いつかなくなり(飢餓状態になり)、別のがんは宿主の免疫系やその他の防御機構によって認識され(うまく封じ込められ)、またある種のがんはそもそもそれほど攻撃的でない。

Heterogeneity of cancer progression. The arrow labeled “fast” represents a fast-growing cancer, one that quickly leads to symptoms and to death. The arrow labeled “slow” represents a slow-growing cancer, one that leads to symptoms and death but only after many years. The arrow labeled “very slow” represents a cancer that never causes problems because the patient will die of some other cause before the cancer is large enough to produce symptoms. The arrow labeled “nonprogressive” represents cellular abnormalities that meet the pathological definition of cancer but never grow to cause symptoms—Alternatively, they may grow and then regress (dotted line). (Figure 1 was previously supplied by the authors to Wikipedia.)

がん進行の異質性。

「Fast」と書かれた矢印は、進行が速く、すぐに症状が出て死に至るがんを表しています。

「Slow」矢印は、進行が遅く、何年も経ってから症状が現れ、死に至るがんを表しています。

「Very slow」という矢印は、症状が出るほど大きくなる前に他の原因で死亡するため、問題になることがないがんを表しています。

「nonprogressive」と書かれた矢印は、病理学的にがんの定義を満たすが、症状が出るほどには成長しない細胞異常で、成長した後、退縮することもある

(点線)。(図1は、著者らがウィキペディアに提供したものです。)

Overdiagnosis occurs when either nonprogressive cancers or very slow–growing cancers (more precisely, at a slow enough pace that individuals die from something else before the cancer ever causes symptoms) are detected. These two forms of cancer have been collectively referred to as pseudodisease—literally false disease. Although we will not use the term subsequently, another definition of overdiagnosis is simply the detection of pseudodisease.

The conundrum in overdiagnosis is that clinicians can never know who is overdiagnosed at the time of cancer diagnosis. Instead, overdiagnosis can only be identified in an individual if that individual 1) is never treated and 2) goes on to die from some other cause. Because clinicians do not know which patients have been overdiagnosed at the time of diagnosis, we tend to treat all of them. Thus, overdiagnosis contributes to the problem of escalating health-care costs. But even where there no money involved, overdiagnosis would be a major concern: Although such patients cannot benefit from unnecessary treatment, they can be harmed.

過剰診断とは、進行しないがんや非常にゆっくりした進行のがん(正確には、がんが症状を出す前に他の原因で死亡するほどゆっくりした進行のがん)が発見されることである。

この2つの癌を総称して、偽病と呼んでいる。ここではこの用語を使用しませんが、過剰診断のもう一つの定義は、単に偽疾患の発見です。

過剰診断の難問は、臨床医が癌の診断時に誰が過剰診断されたかを知ることができないことである。

むしろ、ある個人が

1)治療されることなく、

2)他の原因で死亡した場合にのみ、過剰診断が確認されるのである。

臨床医は診断時にどの患者が過剰診断されたかを知らないため、すべての患者を治療してしまいがちである。

このように、過剰診断は医療費の増大という問題を引き起こしている。

しかし、お金がかからないところでも、過剰診断は大きな問題であろう。

そのような患者は、不必要な治療によって利益を得ることはできないが、害を受ける可能性はある。

(注・

なんとなく、

過剰診断の難問は、臨床医が癌の診断時に誰が過剰診断されたかを知ることができないことである。

むしろ、ある個人が

1)治療されることなく、

2)他の原因で死亡した場合にのみ、過剰診断が確認されるのである。

という箇所だけを切り取って、「ホラ、症状が出ていてもそれが

過剰診断にあたるかどうか臨床医には区別がつかないじゃないか」

という人が出てきそうですが、ちゃんと文脈を読むと、これは

患者が無症状である場合のみを指しているとしかちょっと解釈のしようがありません。

Prerequisites for Overdiagnosis

The Existence of a Disease Reservoir

過剰診断の前提条件

疾患リザーバーの存在

The first prerequisite for overdiagnosis is the existence a substantial number of subclinical cancers—in other words, a disease reservoir of detectable cancer. Inferences about the size of this disease reservoir come from the methodical inspection of tissues at autopsy in a series of individuals who died from causes other than cancer. This reservoir is most easily investigated in prostate and thyroid cancers because the glands are small enough to allow an exhaustive examination of thin sections of the entire organ. In addition, there have been multiple investigations of the reservoir in breast cancer.

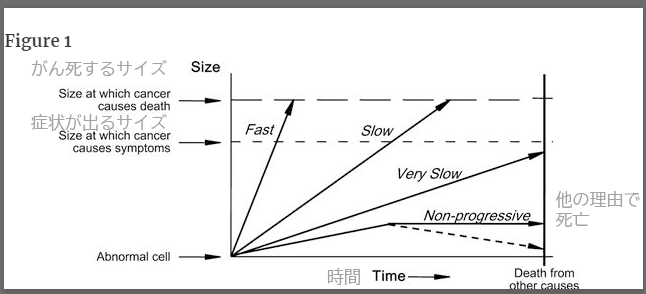

Let us consider the data of two investigators who made age-specific estimates of the reservoir of prostate cancer from autopsies (Figure 2). Sakr et al. (5) examined the prostate glands of 525 American men who died in an accident; Stamatiou et al. (6) examined 212 Greek men who died of other causes and were not found to have palpable prostate cancer. Because additional estimates based on specimens obtained by radical cystectomy are similarly variable (7), it is clear that the reservoir of potentially detectable prostate cancer is highly age dependent and is probably in the range of 30%–70% in men older than 60 years.

過剰診断の第一の前提条件は、相当数の不顕性癌の存在、言い換えれば、検出可能な癌の疾患貯留層があることである。

この疾患貯蔵庫の大きさについての推測は、癌以外の原因で死亡した一連の個人の剖検時の組織を丹念に検査することによって得られる。

前立腺癌や甲状腺癌では、癌腺が小さいため、臓器全体の薄切片を徹底的に調べることができるため、この貯蔵庫の調査が最も容易である。

さらに、乳癌におけるリザーバーの調査も複数行われている。

剖検から前立腺がんのリザーバーを年齢別に推定した2人の研究者のデータについて考えてみよう(図2)。

Sakrら(5)は、事故で死亡した米国人男性525人の前立腺を調べ、tamatiouら(6)は、他の原因で死亡し、触知可能な前立腺がんが見つからなかったギリシャ人男性212人の前立腺を調査した。

根治的膀胱切除術で得られた標本に基づく追加推定値も同様にばらつきがあるため(7)、潜在的に検出可能な前立腺がんの貯蔵庫は年齢に大きく依存し、60歳以上の男性ではおそらく30%~70%の範囲にあることは明らかである。

前立腺がん以外の原因で死亡した男性(生前に前立腺がんであることが判明していなかった人)における前立腺がんの貯留量。

Harach et al. (8) systematically examined the thyroid gland in 101 autopsies. They examined slices of thyroid tissue taken every 2.5 mm and found at least one papillary carcinoma in 36% of Finnish adults. Because many of the cancers were smaller than the width of the slices, they reasoned that they were missing some. Given the number of small cancers they did find and the number that they estimated they had missed (which was a function of size), Harach et al. concluded that the prevalence of histologically verifiable papillary carcinoma would be close to, if not equal to, 100% if one could look at thin enough slices of the gland.

Seven autopsy series have been directed at determining the disease reservoir of breast cancer (9). The four series that included age-specific data suggested that the proportion of middle-aged women who harbored undetected breast cancer ranged from 7% to 39%. Two explanations for this variability are possible that are germane to pathological estimates of the disease reservoir for any cancer. First, different series involve different pathologists, who may have different thresholds about whether to label a small abnormality as “cancer.” Second, different studies have different degrees of scrutiny, that is, some investigators did not look as hard as others. Among the seven series, for example, at one extreme, the investigators examined fewer than 10 slices per breast and at the other extreme, the investigators examined more than 200.

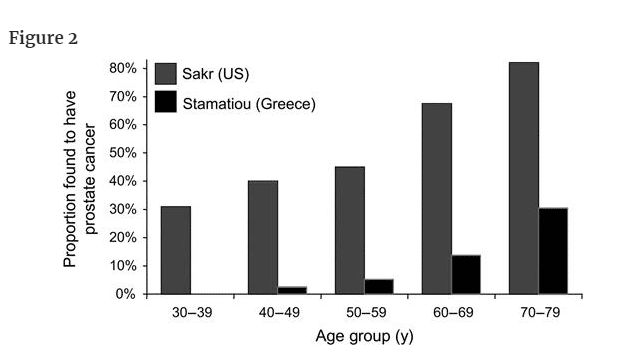

We have summarized the above data in the context of the lifetime risk of death or metastatic disease (Table 1). The lifetime risk of death or metastatic disease is perhaps the least ambiguous measure of the true disease burden for each cancer. The extent to which the disease reservoir exceeds this lifetime risk provides a crude estimate of the amount of overdiagnosis possible.

Harachら(8)は、101人の剖検で甲状腺を系統的に調べた。

彼らは、2.5mmごとに取った甲状腺組織のスライスを調べ、フィンランドの成人の36%に少なくとも1つの乳頭癌を発見した。

多くの癌はスライスの幅より小さかったので、彼らはいくつかの癌を見逃していると推論した。

彼らが発見した小さな癌の数と、彼らが見逃していると推定した数(これは大きさの関数である)を考慮すると、Harachらは、腺の十分薄いスライスを見ることができれば、組織学的に検証可能な乳頭癌の有病率は、100%とまではいかないまでも、それに近いと結論付けている。

7つの剖検シリーズが、乳癌の疾患貯留量を決定することに向けられている(9)。

年齢別のデータを含む4つのシリーズでは、未検出の乳癌を保有する中年女性の割合は7%から39%の範囲であることが示唆された。

このばらつきの原因として、あらゆる癌の疾患貯留量の病理学的推定に関わる2つの説明が可能である。

第一に、シリーズが異なれば病理医も異なり、小さな異常を「癌」と判定するかどうかの閾値も異なる可能性がある。第二に、異なる研究では精査の程度が異なる、つまり、ある研究者は他の研究者ほど厳しく調査していない。例えば、7つのシリーズのうち、ある極端な例では、研究者は乳房あたり10枚未満のスライスを検査し、別の極端な例では、研究者は200枚以上のスライスを検査した。

以上のデータを、死亡または転移の生涯リスクとの関連でまとめてみた(表1)。

死亡または転移の生涯リスクは、おそらく各癌の真の疾病負担を示す最もあいまいな尺度である。

疾患貯留量がこの生涯リスクをどの程度上回っているかによって、過剰診断がどの程度可能かを粗く見積もることができる。

表1

3つの癌に対する疾患貯蔵庫の推定サイズ、死亡または転移性疾患の生涯リスク、および疾患貯蔵庫全体が検出された場合の過剰診断の可能性

生涯死亡または転移性疾患のリスクは、Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Resultsプログラム(10)により報告された生涯死亡リスクに1.33を乗じて推定した。これは、転移性疾患と診断された患者のうち他の原因で死亡する割合が少ない(前立腺がん、甲状腺がん、乳がん転移者のそれぞれ約20%、15%、10%)ことを十分考慮した結果である。

致死性および転移性のがんは、必ずしも有病がん(疾患リザーバーに含まれるがん)から発生するとは限らず、偶発がん(疾患リザーバーに含まれないがん)からも発生するので、この推定値は下限推定値である。

Activities Leading to Detection of the Disease Reservoir

But the existence of a disease reservoir of detectable cancer, by itself, will not lead to overdiagnosis. There must also be actions that tap it. Thus, the second prerequisite for overdiagnosis is activities leading to early cancer detection.

By far, the most obvious of these is cancer screening. The most familiar efforts involve cancer screening programs organized around a single test, such as mammography or prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing. But cancer screening should be conceived more broadly as any effort to detect cancer in those who have no symptoms of the disease. Thus, components of general periodic physical examination, such as searching for moles by closely inspecting the skin or seeking masses by palpating the neck, are also a form of screening.

Furthermore, interventions unrelated to screening can lead to early cancer detection. Pathological inspection of tissues removed in surgeries performed for reasons other than cancer may nonetheless find cancer. The most familiar example is prostate cancer detection following transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia (11). However, the most important activity leading to unintended cancer detection undoubtedly involves the increased use of diagnostic imaging. Detailed imaging of the brain, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis intended to evaluate symptoms not suggestive of cancer nonetheless frequently detect abnormalities worrisome for cancer. Clinicians are familiar with this phenomenon, which is sometimes referred to as the detection of “incidentalomas.” For example, screening for colon cancer with computed tomography (CT) colonography detects extracolonic abnormalities in up to 50% of examinations (12).

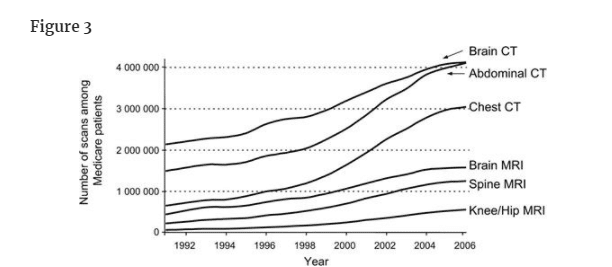

The growth of early cancer detection activities is easiest to measure in organized cancer screening efforts, many of which did not exist two decades ago. Some of the growth is not simply in terms of the number of examinations but also in terms of the increasing sensitivity of the examination itself. It is very difficult to gauge the increase in screening physical examinations because these are not systematically recorded. However, increased use of diagnostic imaging in general is well documented, particularly in the Medicare program (Figure 3) (13).

ディザスターリザーバーの発見につながる活動

しかし、検出可能な癌の疾患貯蔵庫が存在するだけでは、過剰診断にはつながりません。それを掘り起こす行動も必要です。したがって、過剰診断の第二の前提条件は、がんの早期発見につながる活動です。

その中でも、圧倒的にわかりやすいのが、がん検診です。

最も身近な取り組みとしては、マンモグラフィーや前立腺特異抗原(PSA)検査など、1つの検査を中心に組織されたがん検診プログラムがあります。

しかし、がん検診は、病気の症状がない人のがんを発見するためのあらゆる取り組みとして、より広く考えられるべきです。

したがって、皮膚をよく観察してほくろを探したり、頸部を触診して腫瘤を探したりといった一般的な定期健康診断の要素も、スクリーニングの一種である。

さらに、検診とは関係のないところで、がんの早期発見につながることがあります。

がん以外の目的で行われた手術で摘出された組織を病理学的に検査すると、がんが見つかることがあるのです。

最も身近な例は、前立腺肥大症に対する経尿道的前立腺切除術後の前立腺がんの検出である(11)。

しかし、意図しない癌の発見につながる最も重要な活動は、間違いなく、画像診断の利用の拡大である。

がんを示唆しない症状を評価する目的で行われる脳、胸郭、腹部、骨盤の詳細な画像診断では、がんを疑うような異常が頻繁に検出される。

この現象は「偶発腫」の検出と呼ばれ、臨床医にはよく知られている。

例えば、CTコロノグラフィーによる大腸癌のスクリーニング検査では、最大で50%の検査で大腸外の異常が検出される(12)。

早期がん発見活動の成長は、組織的ながん検診の取り組みが最もわかりやすいが、その多くは20年前には存在しなかったものである。

その中には、単に検診の数だけでなく、検診自体の感度が上がっているものもある。

スクリーニングのための人間ドックは体系的に記録されていないため、その増加率を測定することは非常に困難です。

しかし、一般的に画像診断の利用が増加していることは、特にメディケアプログラムにおいてよく知られている(図3)(13)。

米国のメディケア集団で使用された各種検査の件数の推移(1991-2006年)。CT=コンピュータ断層撮影法、MRI=磁気共鳴画像法。

Evidence That Early Detection Has Led to Overdiagnosis

早期発見が過剰診断につながったという証拠

Randomized Trials of Screening

The strongest evidence for overdiagnosis comes from long-term follow-up after a randomized trial of screening. At the end of the trial, it is expected that the screening group will have a greater number of cancers detected than the control group, simply because screening advances the time of diagnosis and moves the detection of some cancers forward in time. If all of the excess of detected disease represents cancers that were destined to progress to clinical disease (ie, there is no overdiagnosis), the excess should disappear over time when both groups receive similar diagnostic scrutiny. In other words, the control group would be expected to “catch-up” to the screening group—because cancers appear clinically because of signs and symptoms. Although the duration of follow-up necessary to completely catch-up is equal to the lead time of the slowest growing cancer, a shorter interval may be sufficient to confirm overdiagnosis given the existence of competing mortality. A persistent excess in the screening group years after the trial is completed constitutes the best evidence that overdiagnosis has occurred.

Breast Cancer.

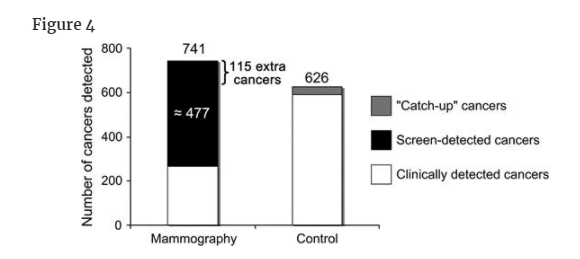

Of the nine randomized trials of mammography, only one has reported long-term follow-up data on incident cancers. The report on 15 years of extended follow-up after the end of Malmö mammographic screening trial provided evidence for breast cancer overdiagnosis (14). At the end of the 10-year trial, 741 breast cancers were detected in the screening group as compared with 591 in the control group. Over the subsequent 15 years, this difference of 150 cancers narrowed to 115, suggesting 35 catch-up cancers. The persistent excess of 115 cancers, however, suggests overdiagnosis.

The findings at the end of the trial, with the 35 catch-up cancers added, highlight a complexity in the estimation of overdiagnosis (Figure 4). One could say that 16% (115 in 741) of cancers detected in the screening group were overdiagnosis. Alternatively, one could restrict the denominator to screen-detected cancers because overdiagnosis can only occur in this subset (a clinically detected symptomatic cancer does not represent overdiagnosis). An earlier publication from the trial showed that 64.4% of cancers detected in the screened group were a consequence of screening, which suggested that about 477 were screen detected. Using this denominator, the risk that a mammographically detected cancer represents overdiagnosis is about 24% (115 in 477) (15).

スクリーニングの無作為化試験

過剰診断の最も強力な証拠は、スクリーニングの無作為化試験後の長期追跡調査から得られる。

試験の終了時には、スクリーニング群では対照群よりも多くのがんが検出されることが予想されるが、これは単にスクリーニングによって診断時期が早まり、一部のがんの検出が時間的に前倒しされるからである。

過剰に検出されたがんがすべて臨床疾患に進行する運命にあったがんである場合(すなわち、過剰診断がない場合)、両群が同様の診断的精査を受けた場合、過剰ながんは時間の経過とともに消失するはずである。

言い換えれば、対照群はスクリーニング群に「追いつく」ことが期待される-がんは徴候や症状によって臨床的に出現するからである。

完全に追いつくのに必要な追跡期間は、最も成長の遅い癌のリードタイムに等しいが、競合する死亡率が存在することを考えると、過剰診断を確認するにはより短い間隔で十分である可能性がある。

試験終了後数年経ってから、スクリーニング群に持続的な過剰があることが、過剰診断が発生したことの最も良い証拠となる。

乳がん

マンモグラフィに関する9件のランダム化試験のうち、がんの発生に関する長期追跡データを報告しているのは1件のみである。

Malmöマンモグラフィースクリーニング試験終了後15年間の長期追跡調査に関する報告は、乳がんの過剰診断の根拠となった(14)。

10年間の試験終了時に、スクリーニング群では741例の乳癌が発見されたのに対し、対照群では591例が発見された。

その後の15年間で、この差は150がんから115がんへと縮小し、35がんのキャッチアップが示唆された。

しかし、115個のがんが持続的に過剰であることは、過剰診断を示唆するものである。

キャッチアップがん35個を加えた試験終了時の所見では、過剰診断の推定が複雑であることが浮き彫りになった(図4)。

スクリーニング群で発見された癌の16%(741例中115例)が過剰診断であったと言うことも可能である。

あるいは、分母をスクリーニングで検出されたがんに限定することもできる。

過剰診断はこの部分集合にのみ起こりうるからである(臨床的に検出された症候性がんは過剰診断とはならない)。

この試験の以前の発表では、スクリーニング群で検出されたがんの64.4%がスクリーニングの結果であったことが示されており、これは約477人がスクリーニングで検出されたことを示唆している。

この分母を用いると、マンモグラフィで検出されたがんが過剰診断であるリスクは約24%(477例中115例)である(15)。

マンモグラフィーのマルメ無作為化試験において,10年後に発見された乳がんのうち,その後の15年間に対照群に出現した35個の「キャッチアップ」がんを追加した数。"追加がん "とは、マンモグラフィ群と対照群の差(対照群にキャッチアップがんを追加した後の値)を指す。これらは、過剰診断されたがんを表していると思われる(オンラインで入手可能な補足技術資料参照)。

Lung Cancer.

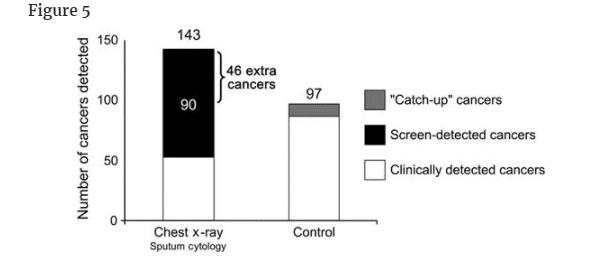

Screening can result in overdiagnosis even among cancers that are traditionally viewed as the most rapidly growing and lethal. The Mayo trial of chest x-ray and sputum cytology screening (16) provided strong evidence for lung cancer overdiagnosis. At the end of the 6-year screening phase, 143 lung cancers were detected in the screening group as compared with 87 in the control group. In follow-up over the subsequent 5 years, 10 catch-up cancers appeared. Extended follow-up over the next 16 years identified no further catch-up cancers (17). Thus, the persistent excess of 46 cancers reflected overdiagnosis (Figure 5). The 46 extra cancers arose among the 90 screen-detected cases in the screening group. Using this denominator, the risk that a chest x-ray– and/or sputum cytology–detected cancer represents overdiagnosis is about 51% (46 in 90).

肺がん

従来、最も成長が早く致死率が高いとされてきた癌であっても、スクリーニングは過剰診断につながることがある。

胸部X線と喀痰細胞診のスクリーニングに関するMayo試験(16)は、肺癌の過剰診断の強い証拠を示した。

6年間のスクリーニング期間の終了時に、スクリーニング群では143の肺癌が検出されたのに対し、対照群では87であった。

その後の5年間のフォローアップでは、10個のキャッチアップがんが出現した。

その後16年間の延長した追跡調査では、それ以上のキャッチアップがんは確認されなかった(17)。

したがって、46個の癌の持続的過剰は過剰診断を反映していることになる(図5)。

46個の余分ながんは、スクリーニング群の90例のうち、スクリーニングで検出された症例から発生したものである。

この分母を用いると、胸部X線検査および/または喀痰細胞診で検出されたがんが過剰診断であるリスクは約51%(90人中46人)である。

胸部X線検査と喀痰細胞診によるスクリーニングのMayo clinic無作為化試験において、6年後に発見された肺癌の数に、その後の5年間に対照群に出現した10個の「キャッチアップ」癌を追加した数。"追加がん "とは、スクリーニング群と対照群の差(対照群にキャッチアップがんを追加した後の差)を指す。これらは、過剰診断されたがんを表していると思われる(オンラインで入手可能な補足技術資料参照)。

Prostate Cancer.

Although there has been no long-term follow-up, the recently reported randomized trials of PSA screening for prostate cancer also provide some insight into overdiagnosis. The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer (PLCO) trial (18) suffered from substantial contamination (ie, screening in the control group) and found no difference in prostate cancer mortality, nonetheless there was a 22% increase in prostate cancer detection in the screening group. It is not known whether this excess will ultimately be diminished by the appearance of catch-up cancers in the control group.

The European Randomized Study of Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) trial (19) used a lower PSA threshold for biopsy (3 vs 4 ng/mL) and a longer screening interval (every 4 years vs annually) and is believed to have had less contamination than the PLCO trial. It found that PSA screening was associated with a 20% reduction in prostate cancer mortality. There was a 70% increase in prostate cancer detection in the screening group—an extra 34 prostate cancers per 1000 men screened. This excess arose from the 58 screen-detected prostate cancers per 1000 men. If this excess represents overdiagnosis, the risk that a PSA-detected cancer represents overdiagnosis would be about 60% (0.034 in 0.058). However, it could be argued that there has been insufficient follow-up for catch-up cancers to become evident and that, therefore, this risk could be an overestimate.

A prior publication by the European group (20) suggested that the risk of overdiagnosis is, in fact, about this magnitude. The investigators estimated that 48% of all patients diagnosed in the screened group (which included both PSA- and clinically detected cancers) had been overdiagnosed (20). Application of that estimate to 82 per 1000 men diagnosed in the screening group during the trial would suggest that overdiagnosis had occurred in about 39 per 1000 men. Using this estimate, the risk that a PSA-detected cancer represents overdiagnosis is about 67% (0.039 in 0.058).

前立腺がん

長期間の追跡調査は行われていないが、最近報告された前立腺がんに対するPSAスクリーニングのランダム化試験からも、過剰診断に関するいくつかの知見が得られている。

Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer(PLCO)試験(18)は、かなりの汚染(すなわち、対照群でのスクリーニング)に苦しみ、前立腺がん死亡率に差は認められなかったが、それでもスクリーニング群では前立腺がんの発見が22%増加した。この過剰が、対照群におけるキャッチアップがんの出現によって最終的に減少するかどうかは不明である。

European Randomized Study of Prostate Cancer(ERSPC)試験(19)では、生検のPSA基準値が低く(3ng/mL vs 4ng/mL)、スクリーニング間隔が長い(4年ごと vs 毎年)ため、PLCO試験より汚染が少なかったと考えられる。

この試験では、PSAスクリーニングが前立腺がん死亡率の20%低下と関連していることが明らかにされた。

スクリーニング群では前立腺がんの発見が70%増加し、スクリーニングを受けた男性1,000人当たり34人の前立腺がんが追加された。

この過剰は、スクリーニングで検出された1,000人当たりの前立腺がん58個から生じている。この過剰が過剰診断であるとすれば、PSAで検出されたがんが過剰診断であるリスクは約60%(0.058分の0.034)であろう。

しかし、キャッチアップがんが明らかになるまでの追跡調査が不十分であったため、このリスクは過大評価である可能性もある。

欧州のグループによる先行発表(20)では、過剰診断のリスクは実際この程度であることが示唆されている。

研究者らは、スクリーニング群(PSA検査によるがんと臨床的に発見されたがんの両方を含む)で診断された全患者の48%が過剰診断であったと推定した(20)。この推定値を試験中にスクリーニング群で診断された1000人当たり82人に適用すると、1000人当たり約39人に過剰診断が発生したことになる。この推定値を用いると、PSAで検出されたがんが過剰診断であるリスクは約67%(0.058分の0.039)である。

Observational Studies

Observational studies can also provide good evidence for overdiagnosis. In one striking example, investigators in Japan reported, after a first round of spiral CT screening (ie, prevalence screen), finding almost 10 times as much lung cancer as they had previously found in the same population using chest x-rays (21). At the completion of the 3-year screening program, lung cancer detection was virtually the same in smokers as that in never-smokers (22), producing a relative risk that approached 1:

Because a wealth of epidemiological investigation has demonstrated that the risk of smokers dying from lung cancer is at least 15 times higher than that of never-smokers (23), the Japanese data (the only large-scale CT screening study to include a similar proportion of smokers and nonsmokers) provide evidence that overdiagnosis can be a substantial problem with spiral CT screening.

Japanese investigators have also studied screening for a rare neuroendocrine cancer in children: neuroblastoma (24). Following the initiation of a national screening program, the number of children diagnosed with neuroblastoma more than doubled, and it went up almost fivefold in the group being screened—children younger than 1 year of age. Because some Japanese physicians were concerned about this trend (25), a group of pediatric oncologists decided to offer a “watchful waiting” strategy to the parents of infants with small cancers that were not obviously doing damage (26). Of the 17 couples offered the strategy, 11 accepted, and in each infant, the cancer regressed. Thus, these 11 cancers represented overdiagnosis. Subsequent studies of large-scale screening in Germany and Quebec found that screening detected about twice as many cancers as expected (suggesting overdiagnosis) but no change in neuroblastoma mortality (27,28).

観察研究

観察研究は、過剰診断の良い証拠にもなる。

1つの顕著な例として、日本の研究者は、スパイラルCTスクリーニング(すなわち、有病率スクリーニング)の最初のラウンドの後、同じ集団で以前に胸部X線を用いて発見した肺癌のほぼ10倍を発見したと報告している(21)。

3年間のスクリーニング・プログラムが終了した時点で、喫煙者における肺癌検出率は非喫煙者とほぼ同じであり(22)、相対リスクは1に近かった。

豊富な疫学調査により、喫煙者が肺癌で死亡するリスクは非喫煙者のそれの少なくとも15倍であることが証明されているので(23)、日本のデータ(喫煙者と非喫煙者の割合が同じである唯一の大規模CTスクリーニング研究)は、スパイラルCTスクリーニングでは過剰診断がかなりの問題となり得ることを示す証拠である。

日本の研究者は、小児におけるまれな神経内分泌癌である神経芽細胞腫のスクリーニングについても研究している(24)。

全国的なスクリーニングプログラムの開始後、神経芽腫と診断された子供の数は2倍以上になり、スクリーニングの対象である1歳未満の子供ではほぼ5倍に増加した。この傾向を懸念する日本の医師もいたため(25)、小児腫瘍専門医のグループは、明らかにダメージを与えていない小さながんを持つ乳児の親に「見守る」戦略を提供することにした(26)。

この戦略を提案した17組のうち、11組がこの戦略を受け入れ、それぞれの乳児で癌は退縮した。したがって、これら11の癌は過剰診断であった。その後、ドイツとケベック州で行われた大規模スクリーニングの研究では、スクリーニングによって予想される数の約2倍のがんが検出されたが(過剰診断を示唆)、神経芽腫の死亡率には変化がなかった(27,28)。

Evidence That Overdiagnosis Is Happening in Populations

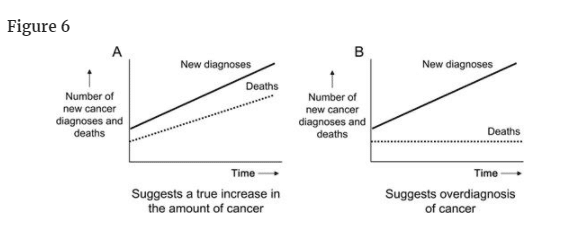

Although it is extremely difficult to assess when overdiagnosis has occurred in an individual, it is relatively easy to assess when overdiagnosis has occurred in a population. Rapidly rising rates of testing and disease diagnosis in the setting of stable death rates are suggestive of overdiagnosis. Let us now consider two hypothetical examples of rapid rises in the rate of diagnosis, one

of which is suggestive of overdiagnosis and the other is not (Figure 6).

集団で過剰診断が起こっている証拠

個人における過剰診断の発生を評価することは非常に困難であるが、集団における過剰診断の発生を評価することは比較的容易である。

死亡率が安定しているにもかかわらず、検査や病気の診断率が急激に上昇している場合は、過剰診断の可能性が示唆される。ここで、診断率が急速に上昇した2つの仮想的な例を考えてみよう。一方は過剰診断の可能性があり、もう一方はそうではない。

診断率の急激な上昇には、2つの明確なパターンがある。A) がんの真の増加を示唆する人口データ、B) がんの過剰診断を示唆する人口データ。

図6の左図では、がん診断の急増に伴い、がんによる死亡が急増している。このパターンは、新しい診断が生命を脅かすものであり、臨床的に重要であることを示唆している。これは、食道腺癌で報告されているパターンである(29)。

図6の右図では、がん診断の急激な上昇に、がん死亡の上昇が伴わない。これは、診断数は増えても、患者さんが罹患する運命にあるがんの根本的な量に変化がないことを示唆しています。これは過剰診断、つまり非常に進行の遅い、あるいは進行しないがんを発見していることを示唆している。

別の説明としては、患者に影響を与えるはずのがんの基礎的な量は実際に増加しているが、診断と治療の改善が偶然(かつ正確に)新規がんの増加を相殺し、がん死亡は変化していない、というものがある。

可能性はあるが、この説明の可能性はあまり高くない。

最も簡潔な説明ではない(1つの仮定ではなく2つの仮定を必要とする)だけでなく、診断や治療の改善速度が真の疾病負担の増加と正確に一致しなければならない(速すぎなければ死亡率は下がり、遅すぎなければ死亡率は上昇する)。

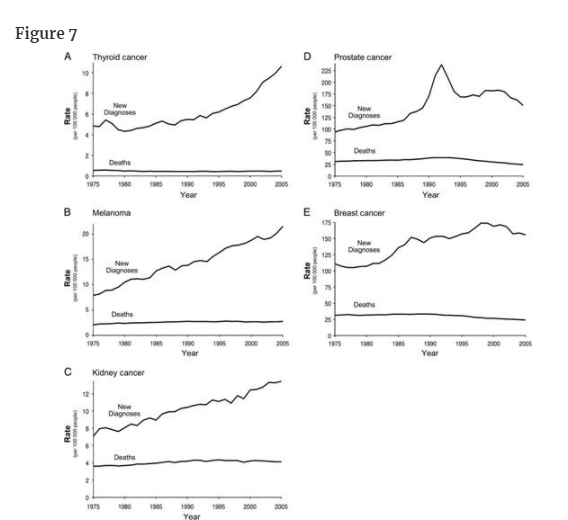

過剰診断に関する最も信頼できる集団ベースの証拠は、Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Resultsが報告した30年間の発生率と死亡率のデータから得られている。5つの癌について、その傾向は新規診断の割合の増加を示しているが、死亡の割合は増加していない(図7)。いずれの場合も、スクリーニングの増加または偶発腫を検出できる画像検査の使用の増加が、新規診断の割合の増加と時間的に関連している。

1975年から2005年までのSurveillance, Epidemiology, and End Resultsデータにおける5つの癌の新規診断と死亡の割合。A) 甲状腺がん B) メラノーマ C) 腎臓がん D) 前立腺がん E) 乳がん

甲状腺がんについては、診断率が2倍以上(10万人あたり4.9人から10.6人)に増加しています。

しかし、甲状腺癌による死亡率は、米国におけるすべての癌の中で最も安定している。

新規診断の増加は、最も予後が良好な組織型(甲状腺乳頭癌)に限られており、ほとんど直径2cm以下の腫瘍で占められている(30)。甲状腺癌の過剰診断は、医師が頸部の腫瘤を触診し(その後、甲状腺超音波検査を紹介する)、他の理由で依頼した超音波検査やCT検査で偶然発見される傾向が強くなっていることを反映していると思われる。

メラノーマの診断率はほぼ3倍になっている(10万人当たり7.9人から10万人当たり21.5人へ)。ここでも、死亡率はおおむね安定しています(過去15年間はほとんど変化なし)。

臨床的に重要な黒色腫の真の増加の要素もあるかもしれないが、これらのデータは、診断の増加のほとんどが過剰診断を反映していることを示唆している。

過剰診断の問題は、皮膚科医にはよく知られている(31-33)。

新規診断のほぼすべてが限局性(またはin situ)黒色腫であり、その出現は人口の皮膚生検率の上昇とほぼ完全に一致しているため、過剰診断がこの上昇の主な説明であると思われる(34)。

腎臓および腎盂のがんについては、診断率は過去30年間でほぼ倍増している(10万人当たり7.1人から10万人当たり13.4人へ)。

しかし、死亡率は安定しており、過去15年間はほとんど変化していない。

最近、53の固形腎腫瘍の成長率に関する調査が行われ、各腫瘍は腎摘出術前に3カ月間隔で少なくとも2回のCT体積測定を行い、その変動する自然史と過剰診断の可能性が示された(35)。

21例(40%)では体積倍加時間が2年以上で、7例(14%)は退縮した。

さらに、緩徐に成長する腫瘍は、高齢者に多く見られた。

したがって、腎腫瘍のかなりの部分は、全く成長しないか、成長が遅すぎて患者が他の原因で死亡する前に腫瘍が症状を引き起こすため、過剰診断となる可能性がある。

これらの腎癌に対する系統的なスクリーニングは行われていないため、診断率の増加は、腹部超音波検査やCTの使用が増加したことによる偶発的な発見の可能性が最も高い。

前立腺癌と乳癌の診断率も上昇している。

しかし、どちらのがんも死亡率が低下しているため、話はより複雑です。

過去15年間で、前立腺がんの死亡率は約3分の1(10万人当たり38.6人から10万人当たり24.6人)、乳がんの死亡率は約4分の1(10万人当たり33.1人から10万人当たり24.0人)に減少しているのです。

この減少は、スクリーニングと治療法の改善の複合的な効果を反映したもので、おそらく乳癌の場合は、ホルモン補充療法が減少したことと、新しい乳房のしこりを持つ女性が早期にマンモグラフィー診断を受けるようになったことが原因であろう。

しかし、どちらの疾患においても、無作為化試験と集団からのデータを総合すると、過剰診断が起こっていることにほとんど疑いの余地はない。したがって、この2つの疾患では、早期発見による死亡率の上昇と同時に、早期発見による過剰診断が存在する可能性が残されているのである。

一方、図7の最初の3つのパネルの場合、発生率の真の増加を相殺し、結果として死亡率を変化させることができる新しい非常に有効な治療法を特定することは困難である。

スクリーニングが広く行われているにもかかわらず、集団で過剰診断が起こっているという証拠がほとんどないがんを強調することが重要である。

子宮頸癌、大腸癌ともに診断率が低下しているため、過剰診断の証拠はほとんどない(オンラインで入手可能な補足技術資料参照)。

これら二つの癌のスクリーニングの結果として過剰診断が起こっているとすれば、それは癌の過剰診断ではなく、前駆病変、例えば子宮頸部異形成や腺腫性ポリープの過剰診断であろう。

Addressing the Problem

Overdiagnosis—along with the subsequent unneeded treatment with its attendant risks—is arguably the most important harm associated with early cancer detection. The impact of false-positive test results is largely transitory, but the impact of overdiagnosis can be life-long and affects patients’ sense of well-being, their ability to get health insurance, their physical health, and even their life expectancy.

For clinicians and patients, overdiagnosis adds complexity to informed decision making: Whereas early detection may well help some, it undoubtedly hurts others. In general, there is no right answer for the resulting trade-off—between the potential to avert a cancer death and the risk of overdiagnosis. Instead, the particular situation and personal choice have to be considered. Often, the decision about whether or not to pursue early cancer detection involves a delicate balance between benefits and harms—different individuals, even in the same situation, might reasonably make different choices.

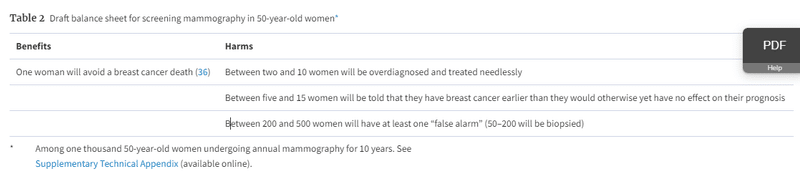

To address overdiagnosis, it is important to ensure that patients are adequately informed of the nature and the magnitude of the trade-off involved with early detection. This kind of discussion has been widely advocated as part of PSA screening but is nevertheless challenging for patients. They must first clearly understand the nature of the trade-off that although early diagnosis may offer the opportunity to reduce the risk of cancer death, it also can lead one to be diagnosed and treated for a “cancer” that is not destined to cause problems. Then, they must understand the magnitude of the trade-off. Each idea will be foreign and difficult, so they must be presented very clearly. We believe that this is best done through the construction of simple one-page balance sheets that frame the trade-off. We have provided one such example for screening mammography (Table 2).

問題への対処

過剰診断は、その後に続く不必要な治療とそれに伴うリスクとともに、がんの早期発見に伴う最も重要な害悪であることは間違いない。

検査結果の偽陽性は一過性のものであるが、過剰診断の影響は一生続くものであり、患者の幸福感、健康保険加入の可否、身体の健康、さらには生命予後にまで影響を及ぼす。

臨床医と患者にとって、過剰診断は情報に基づいた意思決定に複雑さを加える。

早期発見によって助かる人がいる一方で、間違いなく傷つく人もいる。

一般に、がんによる死亡を回避できる可能性と過剰診断のリスクとの間のトレードオフについて、正しい答えはない。

むしろ、特定の状況や個人の選択を考慮しなければならない。

多くの場合、がんの早期発見を目指すかどうかの決断は、利益と害の微妙なバランスを伴うものであり、同じ状況にあっても、個人によって合理的に異なる選択をする可能性がある。

過剰診断に対処するためには、早期発見に伴うトレードオフの性質とその大きさについて、患者に十分な情報を提供することが重要である。

このような議論は、PSA検診の一部として広く提唱されているが、それでも患者にとっては困難である。

早期診断によってがん死亡のリスクを減らすことができるかもしれないが、問題を起こす運命にはない「がん」の診断と治療を受けることになるかもしれないというトレードオフの本質をまず明確に理解する必要がある。

そして、そのトレードオフの大きさを理解することです。

一つひとつの考え方が異質で難しいので、非常にわかりやすく提示することが必要です。そのためには、トレードオフをフレーム化したシンプルなバランスシートを1ページで作成することが最適だと考えています。マンモグラフィ検診の例(表2)をご覧ください。

50歳女性におけるマンモグラフィ検診のバランスシート(案)※。

メリット

1人の女性が乳がんによる死亡を回避することができる

ハーム

2~10人の女性が過剰診断され、不必要な治療を受けることになる。

5~15人の女性が、予後に影響を与えない程度に早く乳がんであることを告げられる。

200~500人の女性が少なくとも1回は「誤警報」を受ける(50~200人は生検を受ける)。

The exercise of drafting a balance sheet highlights another important response: researchers need to work to develop reliable estimates of the magnitude of overdiagnosis. Consider the mammography example. In Malmo, there were 62 fewer breast cancer deaths and 115 women overdiagnosed (14)—a ratio of one breast cancer death avoided to two women overdiagnosed; yet others have argued that the ratio is 1 to 10 (37).

Admittedly, quantifying overdiagnosis is challenging. There are relatively few randomized trials of screening to start with, and even fewer will provide the needed long-term follow-up data. Nevertheless, even “best guess” estimates about the magnitude of overdiagnosis may play an important role in decision making. This effort will undoubtedly require modeling the natural history of the cancer, the impact of early diagnosis, and competing mortality. Although complex models may offer the highest degree of precision, their complexity can make it difficult for outsiders to review (or, in fact, even know) their structure and assumptions. Thus, we believe that there is an important place for more simple and transparent models in which all the assumptions, input values, and calculations are explicit and can be contained in a single spreadsheet.

A third response is to better understand patients’ values regarding overdiagnosis. But researchers cannot understand patient values before patients understand the trade-off. Thus, efforts to determine preferences will need to be preceded by efforts to educate patients. Learning how sensitive patient preferences are to overdiagnosis (eg, whether changing the trade-off from 1:2 to 1:10 influences the decision to have mammography) will help inform us about how precise the estimates of overdiagnosis need to be.

A fourth response is to develop clinical strategies to help mitigate overdiagnosis. Overdiagnosis creates a powerful cycle of positive feedback for more overdiagnosis because an ever increasing proportion of the population knows someone—a friend, a family member, an acquaintance, or a celebrity—who “owes their life” to early cancer detection. Some have labeled this the popularity paradox of screening: The more overdiagnosis screening causes, the more people who feel they owe it their life and the more popular screening becomes (38). The problem is compounded by messages (in the media and elsewhere) about the dramatic improvements in survival statistics, which may not reflect reduced mortality, but instead be an artifact of overdiagnosis—diagnosing a lot of men and women with cancer who were not destined to die from the disease (39).

It is possible that new insights from genomics will ultimately allow us to more accurately predict tumor behavior at the individual level. However, the field has not advanced to that point yet. We must explore other clinical strategies. One potential strategy to mitigate overdiagnosis is to raise the threshold to label a test as “abnormal” or the threshold to intervene. The diagnostic thresholds for common screening tests typically had their origins in arbitrary decisions (eg, PSA > 4 ng/mL). And the tendency over time has been for these thresholds to fall—either because we can see more (eg, microcalcifications on a mammogram) or because we learn that individuals below the threshold can still have cancer (leading some to argue for biopsies for PSA > 2.5 ng/mL).

The problem of overdiagnosis provides the motivation to investigate the other direction—testing higher diagnostic thresholds for labeling a screening test abnormal. One threshold to test is that of size—It may be better to simply ignore small abnormalities. This approach already has precedent in the use of size criteria to manage small pulmonary nodules (40) and adrenal lesions (41,42) incidentally detected on CT. There is an analogous threshold to test in laboratory values (such as a PSA)—that of magnitude—where it may be better to ignore what are now considered small elevations.

But most important may be to add an additional threshold that must be observed before labeling a screening test abnormal—that of growth. In spiral CT screening for lung cancer, demonstrating the growth of small lesions is now accepted as a prerequisite for biopsy—even among ardent screening proponents (43). Testing the effect of higher thresholds in randomized trials would offer the opportunity reduce not only overdiagnosis but also false-positive results.

Finally, there is much work to be done to incorporate the concept of overdiagnosis into the medical curriculum. Enthusiasm for new screening tests in the medical community is often based upon preliminary studies with inadequate study designs. Consequently, medical school curricula should incorporate formal coursework on how to evaluate screening tests and how to recognize overdiagnosis.

バランスシートの作成は、もう一つの重要な対応を浮き彫りにしています。

研究者は、過剰診断の大きさについて信頼できる推定値を開発するために努力する必要があります。

マンモグラフィーの例で考えてみよう。

ルメでは、乳がん死亡が62人少なく、過剰診断された女性が115人だった(14)。

これは、過剰診断された女性2人に対して乳がん死亡が1人の割合で回避されたことになるが、この比率は1対10であると主張する人もいる(37)。

確かに、過剰診断の定量化は困難である。

そもそもスクリーニングのランダム化試験は比較的少ないし、必要な長期追跡データを提供できるものはさらに少ない。

それでも、過剰診断の大きさについての「最良の推測」の推定値でさえ、意思決定において重要な役割を果たすかもしれない。

この努力には、がんの自然史、早期診断の影響、および競合する死亡率をモデル化することが間違いなく必要であろう。

複雑なモデルは最高の精度を提供するかもしれないが、その複雑さゆえに、部外者がその構造や仮定を検討する(あるいは、実際には知ることさえ)ことが困難となる場合がある。

したがって、すべての仮定、入力値、計算が明示され、1枚のスプレッドシートに収められるような、よりシンプルで透明性の高いモデルが重要な位置を占めると考えられるのである。

第三の対応策は、過剰診断に関する患者の価値観をよりよく理解することである。

しかし、患者がトレードオフを理解する前に、研究者が患者の価値観を理解することはできない。

したがって、患者の嗜好を把握するための努力の前に、患者を教育するための努力が必要となる。

患者の嗜好が過剰診断に対してどの程度敏感であるか(例えば、トレードオフを1:2から1:10に変えることが、マンモグラフィを受けるかどうかの決定に影響するか)を知ることは、過剰診断の推定値をどの程度正確にする必要があるかを知ることに役立つであろう。

4つ目の対応は、過剰診断を軽減するための臨床戦略を開発することである。

過剰診断は、より多くの過剰診断につながる強力な正のフィードバックのサイクルを生み出します。

なぜなら、友人、家族、知人、有名人など、がんの早期発見によって「命を救われた」人を知っている人口の割合は増え続けているからです。

これを「検診人気のパラドックス」と呼ぶ人もいます。

検診が過剰診断を引き起こせば引き起こすほど、検診が命の恩人であると感じる人が増え、検診の人気が高まるのである(38)。

この問題は、生存統計の劇的な改善に関するメッセージ(メディアなど)によってさらに悪化するが、これは死亡率の減少を反映しているのではなく、過剰診断の産物である可能性がある。

ゲノミクスから得られる新たな知見により、最終的には個人レベルでの腫瘍の挙動をより正確に予測できるようになる可能性がある。

しかし、この分野はまだそこまで進んでいない。

我々は、他の臨床戦略を模索しなければならない。過剰診断を緩和するための一つの可能性のある戦略は、検査を「異常」とする閾値、あるいは介入する閾値を上げることである。

一般的なスクリーニング検査の診断閾値は、通常、恣意的な判断に由来している(例えば、PSA > 4 ng/mL)。

そして、時間の経過とともに、これらの閾値は低下する傾向にある。それは、より多く見ることができるため(例えば、マンモグラムの微小石灰化)、あるいは、閾値以下の個人にも癌があることが分かったため(PSA > 2.5 ng/mLの生検を主張する者がいる)である。

過剰診断の問題は、スクリーニング検査を異常と判定するためのより高い診断閾値を調べるという、別の方向への動機付けとなる。

検査すべき閾値の1つは、大きさである。

小さな異常は単に無視する方がよいかもしれない。

このアプローチは、CTで偶然発見された小さな肺結節(40)や副腎病変(41,42)を管理するためにサイズ基準を使用することですでに前例がある。

検査値(PSAなど)には、現在では小さな上昇とみなされているものを無視したほうがよいという、大きさの基準という類似の検査値がある。

しかし、最も重要なことは、スクリーニング検査を異常と判定する前に観察されなければならない閾値、すなわち成長の閾値を追加することであろう。

肺癌のスパイラルCT検診では、小さな病変の成長を示すことは、熱心な検診支持者の間でさえ、生検の前提条件として受け入れられている(43)。より高い閾値の効果を無作為化試験で検証することは、過剰診断だけでなく、偽陽性結果を減らす機会を提供することになるであろう。

最後に、過剰診断の概念を医学のカリキュラムに取り入れるために、やるべきことは多い。医学界における新しいスクリーニング検査に対する熱意は、しばしば不十分な研究デザインの予備的な研究に基づいている。したがって、医学部のカリキュラムには、スクリーニング検査の評価方法と過剰診断の認識方法に関する正式なコースワークを取り入れるべきである。

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?