Overdiagnosis: epidemiologic concepts and estimation (Bae, 2015)

Abstract

Overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer was propounded regarding the rapidly increasing incidence in South Korea. Overdiagnosis is defined as ‘the detection of cancers that would never have been found were it not for the screening test’, and may be an extreme form of lead bias due to indolent cancers, as is inevitable when conducting a cancer screening programme. Because it is solely an epidemiological concept, it can be estimated indirectly by phenomena such as a lack of compensatory drop in post-screening periods, or discrepancies between incidence and mortality. The erstwhile trials for quantifying the overdiagnosis in screening mammography were reviewed in order to secure the data needed to establish its prevalence in South Korea.

概要

韓国で急増している甲状腺がんの発生率について、過剰診断が提唱された。過剰診断とは、「スクリーニング検査がなければ発見されなかったであろうがんが発見されること」と定義され、がん検診プログラムを実施する際に避けられない、低年齢がんによるリードバイアスの極端な形態である可能性が指摘されている。あくまで疫学的な概念であるため、検診後の代償的な低下や、発生率と死亡率の不一致などの現象によって間接的に推定することができる。マンモグラフィ検診における過剰診断の定量化のための過去の試行を検討し、韓国における過剰診断の有病率を確定するために必要なデータを確保することを目的とした。

INTRODUCTION

According to the 2011 National Cancer Statistics in South Korea (hereafter Korea), thyroid cancer showed the highest annual percentage change (APC) at 23.3% [1]. Such an epidemic was suggested to be caused by overdiagnosis [2,3]. However, if the definition of overdiagnosis is not shared accurately, it can turn into a medical ethics issue that may lead to healthcare providers performing unnecessary treatment. Moreover, when the extent of overdiagnosis is not quantified, the public health policy implications cannot be properly addressed.

An overdiagnosis controversy already exists with respect to prostate, breast, renal, and thyroid cancer in Western countries [4], expressed as ‘an epidemic of diagnosis’ [5]. There has been suspicion of overdiagnosis, particularly on performing mammography for the early diagnosis of breast cancer, which has been performed since the 1980s [6]. This has greatly impacted the medical field after 2000 [7], including diverse studies focused on estimating the extent of overdiagnosis [8,9].

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the implications of the definition of overdiagnosis, focusing on papers regarding mammography overdiagnosis. The study also aims to organize quantification methods to estimate the extent of overdiagnosis, as well as qualification criteria to confirm its presence. Based on this, another goal of the present study was to check the feasibility of quantification methods in Korean conditions and to further investigate which data should be secured in the future. Such attempts are expected to provoke evidence-based medical discussion regarding the overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer, which is a current controversy.

はじめに

2011年の韓国(以下、韓国)の全国がん統計によると、甲状腺がんは23.3%と最も高い年間変化率(APC)を示している[1]。

このような流行は、過剰診断が原因であることが示唆された[2,3]。

しかし、過剰診断の定義が正確に共有されていないと、医療者が不必要な治療を行うことになりかねず、医療倫理上の問題に発展する可能性がある。

さらに、過剰診断の程度が定量化されていない場合、公衆衛生政策への影響も適切に対処することができない。

欧米諸国では、前立腺がん、乳がん、腎がん、甲状腺がんに関して、すでに過剰診断論争が存在し [4] 、「診断の流行」と表現されている [5] 。

特に、1980年代から行われている乳がんの早期診断のためのマンモグラフィーの実施については、過剰診断の疑いが指摘されている[6]。

これは2000年以降の医療現場に大きな影響を与え[7]、過剰診断の程度を推定することに焦点を当てた多様な研究が行われている[8,9]。

そこで、本研究の目的は、マンモグラフィーの過剰診断に関する論文を中心に、過剰診断の定義が持つ意味について検討することである。

また、過剰診断の程度を推定するための定量化手法や、その存在を確認するための適格基準を整理することも本研究の目的とする。

これを踏まえて、韓国の状況における定量化手法の実現可能性を確認し、今後どのようなデータを確保すべきかをさらに検討することも本研究の目的であった。このような試みは、現在論争になっている甲状腺がんの過剰診断に関して、エビデンスに基づく医学的議論を喚起するものと期待されます。

MAIN BODY

Change pattern in cancer incidence according to cancer screening

When a cancer screening program for the purpose of decreasing mortality via early diagnosis is newly initiated or more precise diagnostic devices are introduced, the incidence of corresponding cancer is increased [10], but the change pattern differs by the time of screening [11,12]. At the beginning of screening, incident cases as well as prevalent cases at lead time are detected and diagnosed, thereby exhibiting a rapid increase in incidence [13-16]. As the screening program is continued, only incident cases are detected, with the incidence manifesting as a stable increase [17,18]. Once a screening program is not provided, as with subjects approaching old age, it shows a complementary drop phenomenon whereby the incidence suddenly decreases (because the incident cases at lead time have already been diagnosed), and then converges to the level of non-screening group incidence [9,19-21]. Biesheuvel et al. [9] schematized such a change pattern.

Meanwhile, change patterns vary depending on incidence levels and trends, implementation extent and accuracy of screening methods, and extent of overdiagnosis [22,23]. Accordingly, a cancer screening program inevitably results in overdiagnosis [24-28]. Therefore, the increase in incidence should not be simplified as an outcome of overdiagnosis [29].

本文

がん検診によるがん罹患率の変化パターン

早期診断による死亡率低下を目的としたがん検診が新たに開始されたり、より精密な診断機器が導入されたりすると、対応するがんの発生率が上昇するが[10]、その変化パターンは検診時期によって異なる[11,12]。

検診開始当初は、リードタイムの有病者だけでなく、偶発症も検出・診断されるため、発生率が急速に上昇する[13-16]。

スクリーニングプログラムを継続すると、偶発症例のみが検出され、罹患率は安定した増加を示すようになる[17,18]。

老年期のようにスクリーニングプログラムが提供されなくなると、(リードタイムの偶発症例がすでに診断されているため)発生率が突然低下し、その後、非スクリーニング群の発生率の水準に収束するという相補的低下現象を示す [9,19-21].

Biesheuvelら[9]はこのような変化パターンを図式化した。

一方、変化パターンは、罹患率レベルやトレンド、スクリーニング方法の実施範囲や精度、過剰診断の程度によって異なる [22,23]。

したがって、がん検診プログラムは必然的に過剰診断となる [24-28]。

したがって、発生率の増加を過剰診断の結果と単純化すべきではない [29]。

Definition of overdiagnosis

Table 1 shows sentences with definitions found in papers relevant to the overdiagnosis of screening mammography [4,9,16, 20,24,25,28-44]. Tracing back the year of publication, they are based on the definition by Prorok et al. [30] in 1999, which is ‘the detection of cancers that would never have been found were it not for the screening test.’

Table 1.

The related sentences for defining overdiagnosis in cancer screening

Author (published year) [reference] Sentence

Prorok et al. (1999) [30] The detection of cancers that would never have been found were it not for the screening test

Etzioni et al. (2003) [31] The detection of cancers that would otherwise not have been detected in the remaining life span of the individuals

Zahl et al. (2004) [32] The detection of low malignancy lesions that otherwise would not be detected in a patient’s lifetime

Day (2005) [33] Lesions that are detected at screening but which would not have surfaced clinically in the lifetime of the individual

Moss (2005) [34] The diagnosis of invasive or in situ breast cancer that, in the absence of screening, would not have presented clinically during the woman's lifetime

de Koning et al. (2006) [35] The detection of cancers by screening that would otherwise never have been clinically diagnosed but are now consequently treated

Paci & Duffy (2005) [29] Diagnosis of cancer that would not have led to clinically manifested disease in a woman's lifetime, in the absence of screening

Warren & Eleti (2006) [36] Diagnosis of cancers that would not present during the lifetime of the patient and is one of the downsides of screening

Biesheuvel et al. (2007) [9] The detection with screening of cancer that would not have presented clinically during the ‘woman's lifetime (and therefore would not be diagnosed in the absence of screening)'

Mandelblatt et al. (2009) [37] The proportion of cases in each strategy that would not have clinically surfaced in a woman's lifetime among all cases

Duffy et al. (2010) [38] The diagnosis of a cancer as a result of screening that would not have been diagnosed in the ‘woman's lifetime had screening not taken place

Welch & Black (2010) [4] The diagnosis of a “cancer” that would otherwise not go on to cause symptoms or death

Seigneurin et al. (2011) [39] The proportion of non-progressive cancers among all cases of invasive cancer and carcinoma in situ

Gunsoy et al. (2012) [40] The diagnosis of screen detected cancers that would not have presented clinically in a lifetime in the absence of screening

Hellquist et al. (2012) [16] The excess of cancers diagnosed with screening compared with without screening that is not due to earlier diagnosis

Marmot (2012) [41] The diagnosis of cancer as a result of screening which would not have been diagnosed in the patient's lifetime had screening not taken place

Puliti et al. (2012) [20] The detection of a cancer at screening, histologically confirmed, that would never have been identified clinically in the lifetime of the woman

Yen et al. (2012) [42] The diagnosis of cancer as a result of screening that would not have arisen in the lifetime of the host

Etzioni et al. (2013) [43] Excess cases detected because of cancer screening

Miller (2013) [25] The detection by screening of a cancer not destined to present clinically in the person's lifetime

Zahl et al. (2013) [24] The detection of lesions that would never have been detected in a persony in the lein the absence of screening

Cervera et al. (2014) [28] The detection of a disease that would have gone undetected without screening when that disease would not have resulted in morbimortality and was treated unnecessarily

Pace & Keating (2014) [44] The detection of a tumor through screening that would not have become clinically evident in the absence of screening

過剰診断の定義

表1は、マンモグラフィ検診の過剰診断に関連する論文[4,9,16, 20,24,25,28-44] に見られる定義の文章を示したものである。

発表年をさかのぼると、1999年のPlorokらによる定義[30]に基づいており、「スクリーニング検査を受けていなければ発見されることのなかったがんが発見されること」である。

表1.

がん検診における過剰診断の定義に関連する文章

著者(発表年) 【参考】 文章

Prorokら(1999)[30] スクリーニング検査がなければ発見されることのなかったがんが発見されること。

Etzioni et al. (2003) [31] 個人の残りの寿命では発見されなかったであろうがんの発見

Zahl et al. (2004) [32] 患者の生涯に渡って発見されないような低悪性度病変の発見

Day (2005) [33] 検診で発見されたが、その個人の生涯において臨床的に表面化しなかったであろう病巣

Moss (2005) [34] スクリーニングがなければ、女性の生涯に臨床的に現れなかったであろう浸潤性または非浸潤性乳がんの診断。

de Koning et al. (2006) [35] スクリーニングによって発見された、他の方法では臨床的に診断されることはなかったが、結果的に治療されることになった癌の発見

Paci & Duffy (2005) [29] 検診を受けなかった場合、女性の生涯において臨床的に顕在化することのなかったであろうがんの診断

Warren & Eleti (2006) [36] 患者の一生の間に発症しないであろう癌の診断であり、スクリーニングのデメリットの一つである。

Biesheuvel et al. (2007) [9] 「女性の一生」の間に臨床的に現れなかったであろう(したがって、スクリーニングがなければ診断されなかったであろう)癌のスクリーニングによる発見

Mandelblatt et al. (2009) [37] 各戦略における、女性の生涯において臨床的に表面化しなかったであろう症例の全症例中における割合

Duffy et al. (2010) [38] スクリーニングの結果、「女性の生涯において、スクリーニングが実施されなければ診断されなかったであろうがん」が診断されたこと

Welch & Black (2010) [4] 他の方法では症状や死亡に至らない「がん」と診断された場合

Seigneurin et al. (2011) [39] 浸潤癌および非浸潤癌の全症例における非進行性癌の割合

Gunsoy et al. (2012) [40] スクリーニングにより発見されたがんのうち、スクリーニングを行わなければ生涯に渡って臨床的に現れなかったであろうがんの診断数

Hellquist et al. (2012) [16] スクリーニングによって診断されたがんのうち、早期診断によるものではないものの、スクリーニングなしと比較した場合の過剰数

] スクリーニングの結果、患者の生涯において、スクリーニングが実施されなければ診断されなかったであろうがんの診断

Puliti et al. (2012) [20] 生涯で一度も臨床的に確認されることのなかったがんが、組織学的に確認され、検診で発見されること。

Yen et al. (2012) [42] 宿主の生涯に生じなかったであろうがんが、スクリーニングの結果として診断されること。

Etzioni et al. (2013) [43] がん検診が原因で発見された過剰症例

Miller (2013) [25] 生涯に渡って臨床的に現れる運命にないがんが検診で発見されること。

Zahlら(2013)[24]検診を受けなければ決して発見されなかった病変が発見されたこと

Cervera et al. (2014) [28] 検診を受けなければ発見されなかったであろう病気が発見され、その病気が罹患率に至らず、不必要に治療された場合。

Pace & Keating (2014) [44] スクリーニングにより、スクリーニングがなければ臨床的に明らかにならなかったであろう腫瘍が発見されたこと。

However, there are a couple of tiny differences. First, detection was used interchangeably with diagnosis [45,46] because the term ‘overdetection’ implies that it is the result of implementing unnecessary screening tests [9,47]. However, the definitions in Table 1 need to be differentiated by whether an object of detection or diagnosis is cancer or lesion. Although Zahl et al. [32] and Day [33] highlighted lesion, the remainder was predominantly specified as cancer, and cancer diagnosis should always accompany patho-histological judgments. Based on these, the term overdiagnosis seems more reasonable than overdetection. Second is the distinction as to whether it includes invasive cancer as well as carcinoma in situ. Zahl et al. [32] stated these cases as ‘low malignancy lesions’, whereas Moss [34] and Seigneurin et al. [39] emphasized the inclusion of invasive cancer. As the progression of diagnosed cancer cells can be different [4,48,49] and some cases undergo regression [50-53], it is reasonable to include invasive cancers as well [44,48]. Third, regarding conditions that are only detected with screening tools, Seigneurin et al. [39] emphasized their ‘non-progressive’ nature, and Cervera et al. [28] interpreted them as ‘not having resulted in morbimortality’. As final results of subjects diagnosed by screening could be identified after death [43], it is therefore difficult to develop methods for overdiagnosis estimation [4,29,54,55]. Fourth, there is a claim that the term ‘overtreatment’ should be used in lieu of overdiagnosis. Prior to the Prorok et al. [30] statement, Hurley and Kaldor [56] had already been using the term ‘overtreatment of abnormalities’ as a harm of screening mammography in 1992, and Gur and Sumkin [57] suggested using the term ‘overtreatment’ when considering society as a whole, as well as the medical field. However, even in cases of overdiagnosis, treatment may not be received according to one’s level of understanding of the disease and treatment preference based on potential gains or losses related to the outcome [58]. Thus, the term ‘overdiagnosis’ is more appropriate. However, overtreatment is a result of a preceding overdiagnosis [46], and overtreatment is obviously prevented once overdiagnosis is reduced [49].

しかし、いくつかの小さな違いがある。

まず、detectionはdiagnosisと同じ意味で使われた [45,46]。

「過剰検出」という言葉は、不必要なスクリーニング検査を実施した結果であることを意味しているからである [9,47]。

しかし、表1の定義は、検出や診断の対象ががんなのか病変なのかで区別する必要がある。Zahlら[32]やDay[33]は病変を強調しているが、残りは癌と明記することが主流であり、癌診断は常に病態・組織学的判断を伴うべきものである。

これらを踏まえると、overdetectionよりもoverdiagnosisという言葉の方が合理的であると思われる。

第二に、浸潤癌だけでなく、in situ癌も含むかどうかの区別である。

Zahlら[32]はこれらの症例を「低悪性度病変」としているが、Moss[34]やSeigneurinら[39]は浸潤癌を含むことを強調している。

診断された癌細胞の進行は様々であり[4,48,49]、退縮する例もあることから[50-53]、浸潤癌も含めることは妥当である[44,48]。

第三に、スクリーニングツールでのみ検出される疾患について、Seigneurinら[39]はその「非進行性」を強調し、Cerveraら[28]は「病的死亡に至らなかった」と解釈している。

スクリーニングで診断された被験者の最終結果は死後に確認できるため[43]、過剰診断の推定方法を開発することは困難である[4,29,54,55]。

第四に、過剰診断の代わりに「過剰治療」という用語を使用すべきであるという主張がある。

Prorokら[30]の声明に先立ち、Hurley and Kaldor[56]は1992年にすでにマンモグラフィ検診の害として「異常の過剰治療」という用語を用いており、Gur and Sumkin[57]は医療分野だけでなく社会全体を考える際に「過剰治療」という用語を用いるよう提案している。

しかし、過剰診断の場合でも、病気に対する理解の度合いや治療結果に関連する潜在的な利益や損失に基づく治療の嗜好によって、治療を受けられない場合がある [58] 。

したがって、「過剰診断」という用語がより適切である。

しかし、過剰治療は先行する過剰診断の結果であり [46] 、過剰診断が減少すれば過剰治療は明らかに防止される [49] 。

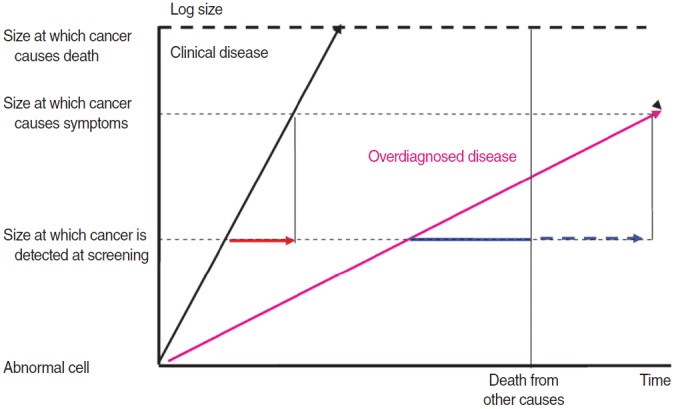

Mechanism of overdiagnosis

Overdiagnosis occurs when non-progressive or regressive cancer is diagnosed, and when deaths are caused by other reasons [4,20,29,36]. Among them, the first indicates an improper control of the interference of length time bias, which is more frequently diagnosed for indolent cancer that shows better prognosis due to slower-than-expected progression where changes in mortality cannot be made, even without treatment [9,49,54, 59-61]. In other words, unknown future progression at the time of diagnosis is a major reason of overdiagnosis [8,20,33]. The occurrence of overdiagnosis according to various cancer progressions was schematized by Welch and Black [4] and Zahl et al. [24] (Figure 1). Due to this background, Esserman et al. [62] proposed the term ‘indolent lesion of epithelial origin (IDLE)’.

過剰診断のメカニズム

過剰診断は、非進行性または退行性のがんが診断された場合、および他の理由によって死亡した場合に起こる[4,20,29,36]。

(*DeepLの翻訳訂正「と」→「が」)

このうち、1つ目は長さの時間的偏りの干渉の不適切なコントロールを示すもので、治療をしなくても死亡率の変化が望めない、予想より遅い進行のため予後が良好な低悪性度がんに対して診断されることが多い [9,49,54, 59-61] 。

つまり、診断時に将来の進行が不明であることが過剰診断の主な理由である [8,20,33]。

様々な癌の進行に応じた過剰診断の発生は、Welch and Black [4]やZahlら[24]によって図式化されている(図1)。

このような背景から、Essermanら[62]は'indolent lesion of epithelial origin (IDLE)'という用語を提唱している。

Figure 1.

Two different types of tumor growth indicated by the black (clinical disease) and pink arrows (overdiagnosed disease). Clinically relevant lead time is indicated by the red arrow. When overdiagnosed tumors are included, some researchers defined lead time as time to death (solid blue arrow, so-called censored lead time), while others included the time to clinical appearance if there had been no competing causes of death (solid plus dotted blue arrow, so-called uncensored lead time). Source from Zahl, et al. Br J Cancer 2013;109:2014-2019, with permission from Oxford University Press [24].

黒い矢印(臨床病変)とピンクの矢印(過剰診断病変)で示される2種類の腫瘍の成長。臨床的に重要なリードタイムは、赤い矢印で示されている。過剰診断された腫瘍を含む場合、リードタイムを死亡までの時間と定義する研究者もいれば(青の実線矢印、いわゆる打ち切りリードタイム)、死因の競合がなかった場合の臨床出現までの時間を含める研究者もいる(青の実線+点線矢印、いわゆる打ち切りなしリードタイム)。出典:Zahl, et al. Br J Cancer 2013;109:2014-2019, Oxford University Pressの許可を得て掲載[24]。

Judgment criteria for the presence of overdiagnosis

and its estimation

When overdiagnosis occurs after the diagnosis of IDLE cancer, a complementary drop phenomenon with respect to incidence does not occur after screening termination [8-10,20,21, 63]; moreover, mortality does not change substantially compared to an increase in incidence [4]. The presence of overdiagnosis is determined based on these two phenomena (Table 2), and these form the base of study by Ahn et al. [2] that claims overdiagnosis as the main cause for the epidemic in thyroid cancer among Koreans.

過剰診断の有無の判断基準とその推計について

IDLEがんの診断後に過剰診断が発生した場合、検診終了後に発生率の相補的低下現象は起こらず [8-10,20,21,63]、さらに死亡率は発生率の増加に比べて大きく変化しない [4]。

これら2つの現象から過剰診断の有無を判断する(表2)。

これらは、過剰診断が韓国人の甲状腺がん流行の主な原因であるとするAhnらの研究[2]の基礎となるものである。

Table 2.

Decision criteria of identifying overdiagnosis

Qualitative Quantitative

Randomized trials No compensatory drop after stopping screening program Excess cases per screen-detected cases (Figure 1)

Observational studies Rapid rising in cancer diagnosis without a following change in mortality Incidence rate ratio between the observed in screen group and the expected in control group

表2.

過剰診断の見極めの判断基準

質的量的

無作為化試験 検診プログラム停止後、代償性低下がない 検診対象症例数あたりの過剰症例数(図1)

観察研究 死亡率に影響を与えず、がん診断が急激に増加した場合 スクリーニング群での観察値と対照群での期待値との罹患率比

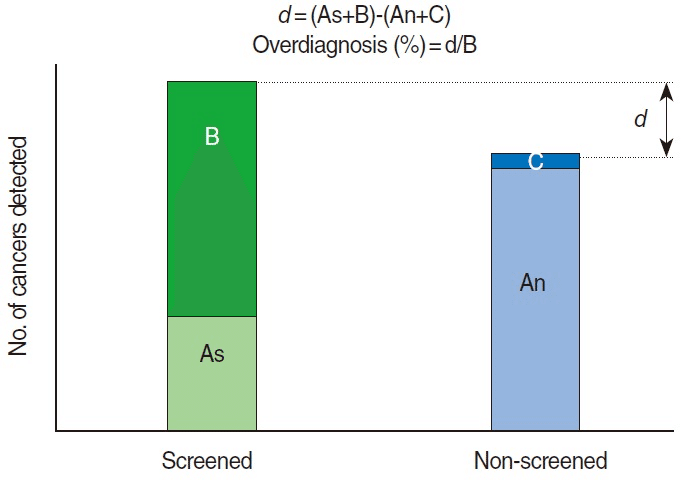

Meanwhile, the definition of overdiagnosis is based on epidemiologic deduction [29] and therefore, the extent of overdiagnosis cannot be directly estimated unless cancer progression can be known in advance at the current medical level [4,10,34,53, 55]. Still, a best guess can be made in the presence of long-term follow-up data with randomized controlled trials [4,25,64,65]. To more conveniently explain the estimation of the extent of overdiagnosis, contents described by Welch and Black [4] are schematized in Figure 2. Cancer identified in a screening group can be classified into cases diagnosed by screening (B) and cases diagnosed by clinical symptom appearance (As). Cancer detected in the control group that did not receive screening can be divided into cases diagnosed by clinical symptom appearance (An) and cases diagnosed after the screening completion (C). The difference between screening group and non-screening group, d (=As+B–An-C), is the extent of overdiagnosis, and the percentage (%) of d with denominator of the cases diagnosed by screening in screening group (B) is the overdiagnosis proportion. While cases diagnosed in the screening group after the screening termination are not further reflected, catch-up cases in the control group (C) are added in order to differentiate over-incident cases by lead time bias and over-incident cases by overdiagnosis [34, 65-67]. The Malmö study had 15 years of additional observation after study completion [67]. If the incidence of the screening group is not reduced after screening termination and remains high compared to the non- screening group, a longer follow-up period is necessary [8,21,68].

一方、過剰診断の定義は疫学的演繹に基づいているため[29]、現在の医学水準でがんの進行が事前に把握できない限り、過剰診断の程度を直接推定することはできない[4,10,34,53,55]。

それでも、ランダム化比較試験による長期の追跡データがあれば、最善の推測が可能である [4,25,64,65]。

過剰診断の程度の推定をより簡単に説明するために、Welch and Black [4]が述べた内容を図2に模式的に示す。

スクリーニング群で発見されたがんは、スクリーニングで診断された例(B)と臨床症状の出現で診断された例(As)に分類される。

検診を受けなかった対照群で発見されたがんは、臨床症状の出現により診断された症例(An)と検診終了後に診断された症例(C)に分けられる。

スクリーニング群と非スクリーニング群の差d(=As+B-An-C)が過剰診断の程度であり、スクリーニング群でスクリーニングにより診断された症例(B)を分母とするdの割合(%)が過剰診断割合である。

スクリーニング終了後にスクリーニング群で診断された症例はそれ以上反映されないが、リードタイムバイアスによる過剰症例と過剰診断による過剰症例を区別するために、対照群のキャッチアップ症例(C)を追加する[34, 65-67]。

Malmöの研究では、研究終了後15年間の追加観察が行われた[67]。

スクリーニング終了後も発症率が低下せず、非スクリーニング群と比較して高いままであれば、より長いフォローアップ期間が必要である [8,21,68] 。

Figure 2.

Extent of overdiagnosis in a randomized trial. As, clinically detected cancers in the screened group; An, clinically detected cancers in the non-screened group; B, screen-detected cancers in the screened group; C, catch-up cancers of post-screening periods in the non-screened group; d, extra cancers. Modified from Welch and Black. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:605-613, with permission from Nature Publishing Group [4].

図2.

無作為化試験における過剰診断の程度。

Asはスクリーニング群の臨床的に検出されたがん、

Anは非スクリーン群の臨床的に検出されたがん、

Bはスクリーニング群のスクリーンで検出されたがん、

Cは非スクリーン群のスクリーニング後のキャッチアップがん、

Dは余分ながん。

Welch and Blackより改変。J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:605-613, Nature Publishing Groupからの許可を得て掲載[4]。

Instead of d that can be obtained by randomized tests (Figure 2), the extent of overdiagnosis in an observational study is considered as the difference between the observed cumulative incidence in the screening group and the expected cumulative incidence in the control group [15,18,42,43,63,69,70]. However, the following four major items should be reviewed in the study plan to secure the validity of the estimated outcomes [9,20]. First, the selection of the non-screening control group should be assessed [27,43,55]. Randomized trials can secure an assumption that the risk of cancer incidence is at the same level irrespective of control or screening group [38,42,67], whereas the best control group that satisfies this assumption should be selected in observational studies [71]. The non-screening group cohort is established based on screening through a prospective cohort study [72], or a historical national control group is proposed via retrospective cohort study prior to the introduction of the screening program [9,10,27,73]. Second, the validity of the methods used to estimate the predicted incidence in the control group should be determined [74,75]. Longstanding incidence rates are needed; therefore, it is important and necessary to have modeling that actively reflects the incidence trend via age-period-cohort (APC) analysis [15,18,39,65,69,75,76]. Third, the conceptual determination of lead time bias [24,77], acceptability of their control methods [4,8,21,53,72,73,78], and confinement of follow-up period ranges [9,10,43,53] are important to this process. Fourth, the possibility of obtaining information to differentiate As and B in Figure 2 for screening group incident cases is important [29]. Although it is easy to obtain information when population-based cancer registry information is utilized in a prospective cohort study [72], survey outcomes performed for other purposes can be derived in a retrospective cohort study [55].

無作為化試験で得られるd(図2)の代わりに、観察研究では過剰診断の程度を、スクリーニング群での観察累積発生率と対照群での期待累積発生率の差として考える [15,18,42,43,63,69,70].

しかし、推定結果の妥当性を確保するためには、研究計画において以下の4つの主要な項目を見直す必要がある[9,20]。

まず、スクリーニングを行わない対照群の選択について評価する必要がある [27,43,55]。

無作為化試験では、対照群やスクリーニング群に関係なく、がん発生リスクが同じレベルであるという仮定を確保できるが [38,42,67] 、観察研究ではこの仮定を満たす最善の対照群を選択する必要がある [71] 。

非スクリーニング群のコホートは、プロスペクティブ・コホート研究によってスクリーニングに基づいて設定され [72]、あるいはスクリーニング・プログラム導入前のレトロスペクティブ・コホート研究によって歴史的全国対照群が提案される [9,10,27,73].

第二に、対照群における予測される発生率を推定するために使用された方法の妥当性を決定する必要がある [74,75]。

長期間の発生率が必要である。

したがって、年齢-期間-コホート(APC)分析によって発生率の傾向を積極的に反映するモデリングが重要かつ必要である [15,18,39,65,69,75,76] 。

第三に、リードタイムの偏り [24,77]、その制御方法の許容性 [4,8,21,53,72,73,78]、追跡期間範囲の限定 [9,10,43,53] の概念決定が、このプロセスにおいて重要である。

第四に、スクリーニング群発生症例について、図2のAsとBを区別するための情報を得ることができるかが重要である[29]。

プロスペクティブ・コホート研究で集団ベースのがん登録情報を活用する場合は情報を得やすいが[72]、他の目的で行われた調査結果はレトロスペクティブ・コホート研究で導き出すことができる[55]。

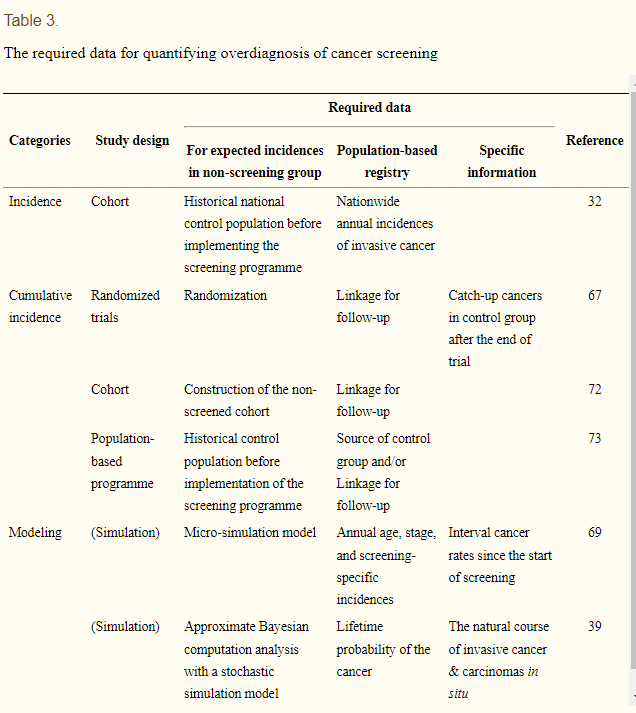

Therefore, observational studies have a variety of estimation methods according to types of control group selection, estimation methods of expected incidence, and lead time control methods [8,20,32,42,43,79]. Biesheuvel et al. [9] classified these diverse study methods into incidence rate, cumulative incidence, and modeling with respect to utilized epidemiologic information. Based on this classification, estimating procedures of the expected incidence in control group, roles of the National Cancer Registry Program, and additionally requested information are summarized in Table 3 in order to identify which studies are plausible in domestic conditions and type of information required in the future. Utilization of cumulative incidence rather than incidence rate is primarily recommended [9,20], and study design differs depending on how to estimate the expected incidence of the control group in Table 3, while the National Cancer Registry Program plays an important role in all cases. Statistical modeling that can reflect the natural history of diseases [9,69] is possible only when such information, including interval cancer [69,80,81] is secured [22,35,39,53]. Considering these and domestic conditions lacking randomized trials for cancer screening, a cohort analysis of cumulative incidence can be performed first if it is known whether the diagnosis was made by screening or was made due to clinical findings [34,72]. If this is challenging, comparative analyses on cumulative incidences between pre- and post-program of cancer screening can be conducted. However, considering that National Cancer Statistics information is available from 2002, estimation methods applying APC can be implemented [55,82].

そのため、観察研究では、対照群の選択の種類、期待発生率の推定方法、リードタイムコントロールの方法などによって、様々な推定方法がある[8,20,32,42,43,79]。

Biesheuvelら[9]は、これらの多様な研究手法を、利用する疫学的情報に関して、発生率、累積発生率、モデリングに分類している。

この分類に基づき、今後、どのような研究が国内において妥当であり、どのような情報が必要かを明らかにするために、対照群における予想発生率の推定方法、全国がん登録制度の役割、追加で求められる情報を表 3 にまとめた。

発生率よりも累積発生率の利用が主に推奨されており[9,20]、表3の対照群の予想発生率をどのように推定するかによって研究デザインが異なるが、いずれの場合もNational Cancer Registry Programが重要な役割を担っている。

疾患の自然史を反映できる統計モデリング[9,69]は、間隔癌[69,80,81]を含め、そうした情報が確保されて初めて可能となる[22,35,39,53]。

これらやがん検診のランダム化試験がない国内事情を考慮すると、検診による診断か臨床所見による診断かがわかれば、まず累積罹患率のコホート解析が可能である [34,72]。

これが困難な場合は、がん検診のプログラム前後での累積罹患率の比較分析を行うことができる。

しかし、2002年から全国がん統計の情報が得られることを考慮すれば、APCを適用した推定法を実施することも可能である[55,82]。

Table 3.

The required data for quantifying overdiagnosis of cancer screening

ategories Study design Required data

Reference

For expected incidences in non-screening group Population-based registry Specific information

Incidence Cohort Historical national control population before implementing the screening programme Nationwide annual incidences of invasive cancer 32

Cumulative incidence Randomized trials Randomization Linkage for follow-up Catch-up cancers in control group after the end of trial 67

Cohort Construction of the non-screened cohort Linkage for follow-up 72

Population-based programme Historical control population before implementation of the screening programme Source of control group and/or Linkage for follow-up 73

Modeling (Simulation) Micro-simulation model Annual age, stage, and screening-specific incidences Interval cancer rates since the start of screening 69

(Simulation) Approximate Bayesian computation analysis with a stochastic simulation model Lifetime probability of the cancer The natural course of invasive cancer & carcinomas in situ 39

表3.

がん検診の過剰診断の定量化のための必要データ

カテゴリー 研究デザイン 必要データ

参考

非検診群における予想発生率について 母集団ベースの登録 特定の情報

発生率 コホート スクリーニングプログラム実施前の過去の全国対照集団 侵襲性癌の全国年間発生数 32

累積発生率 ランダム化試験 ランダム化 追跡調査のためのリンケージ 試験終了後の対照群におけるキャッチアップがん 67

コホート スクリーニングを行わないコホートの構築 フォローアップのための連携 72

母集団ベースのプログラム スクリーニングプログラム実施前の過去の対照集団 対照集団のソースおよび/または追跡調査の連鎖 73

モデリング (シミュレーション) ミクロシミュレーションモデル 年代、病期、スクリーニング特有の発生率 スクリーニング開始からの間隔癌発生率 69

(シミュレーション)確率的シミュレーションモデルによる近似ベイズ計算解析 癌の生涯確率 浸潤癌・非浸潤癌の自然経過 39

CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTION

Estimating the extent of overdiagnosis is a method of investigating the extent of the harms and benefits of screening [38,55], and this is an important evidence for determining public health policies [20,43]. Considering current conditions in Korea, the extent of overdiagnosis can be estimated by establishing a strategy that utilizes statistical results from the Korea Central Cancer Registry database and individual follow-up data as much as possible [65,83]. The barriers are that information regarding whether a diagnosis was made by screening has been collected only in recent years [29], and official statistics have been published since 2002 [34]. To overcome these limitations, national research institutes should promote and lead relevant studies in the optimal use of collectable information.

Despite efforts to validate the utilizing data, there are still limitations left to be addressed regarding the correct interpretation of the estimated extent of overdiagnosis [59,75]. For example, the extent of incidence increase can be differently interpreted according to screening participation rate [43], sensitivity may alter depending on the introduction of new screening methods [54], and risk factors of breast cancer incidence can change (e.g., an increase of oral hormone administration or a change in maternity nursing history) [11,55], and effective treatment methods can be newly developed [55]. Because of these limitations, overdiagnosis estimation ranges of screening mammography are very broad [9,20], and thus there is still controversy on the overdiagnosis [43]. Although a checklist was proposed for the appraisal of related studies [43], an ultimate solution for this controversy is to overcome length time bias causing overdiagnosis [49,54,59-61]. It is therefore necessary to identify the percentage of cancer that has not progressed to invasive cancer in carcinoma in situ [84], the IDLE proportion of overall diagnostic cancer [62], and the percentage of autopsy-based diagnosis [85]. In addition, the Korea Central Cancer Registry has collected information of cancer stage in Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) from 2009 incident cases [1,82], and it is necessary to obtain follow-up results according to the SEER stage regarding thyroid, breast, and prostate cancers, which have been currently controversial in overdiagnosis. Lastly, given the fact that subjects who are negatively impacted from overdiagnosis are healthy individuals [4,27], decision aids allowing for the understanding of losses and gains of correct screening need to be simultaneously developed [58,86].

結論と提案

過剰診断の程度を推定することは、検診の害と益の程度を調べる方法であり[38,55]、公衆衛生政策を決定するための重要な証拠である[20,43]。

韓国の現状を考慮すると、韓国中央癌登録データベースの統計結果と個人の追跡データを可能な限り活用する戦略を確立することで、過剰診断の程度を推定することができる[65,83]。

障壁となるのは、スクリーニングによる診断の有無に関する情報が近年になってようやく収集されたこと [29]、公式統計が2002年から発表されていること [34]である。

これらの限界を克服するために、国の研究機関は収集可能な情報を最適に利用するための関連研究を推進・主導する必要がある。

利用されているデータを検証する努力にもかかわらず、過剰診断の推定範囲の正しい解釈に関して対処すべき限界が残されている [59,75]。

例えば、検診参加率によって罹患率増加の程度が異なって解釈される可能性があり[43]、新しい検診方法の導入により感度が変化する可能性があり[54]、乳癌罹患の危険因子が変化(例えば、経口ホルモン投与の増加や母性看護歴の変化など)[11,55]、有効な治療方法が新たに開発される可能性もある[55]。

これらの制約から、マンモグラフィ検診の過剰診断の推定範囲は非常に広く [9,20]、したがって過剰診断についてはまだ論争がある [43]。

関連研究を評価するためのチェックリストが提案されているが [43]、この論争に対する究極の解決策は、過剰診断の原因となる長時間のバイアスを克服することである [49,54,59-61] 。

したがって、in situがんにおいて浸潤がんに進行していないがんの割合 [84] 、診断がん全体のIDLEの割合 [62] 、剖検に基づく診断の割合 [85] を明らかにすることが必要である。また、韓国中央がん登録では、2009年の発生症例からSurveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results(SEER)のがんステージの情報を収集しており[1,82]、現在過剰診断が議論されている甲状腺がん、乳がん、前立腺がんについてもSEERステージによる追跡結果を得ることが必要であると思われる。

最後に、過剰診断により不利益を被る対象が健常者であることを考慮し [4,27] 、正しいスクリーニングによる損失と利益を理解するための意思決定支援ツールを同時に開発する必要がある [58,86]。

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?