分裂した世界秩序西側諸国はロシアを罰するためなら金融システムの破壊も厭わない

2024 年 3 月 1 日 12:19

ホームビジネスニュース

分裂した世界秩序西側諸国はロシアを罰するためなら金融システムの破壊も厭わない

今日の西側諸国の指導者たちは、大きな変化の時代に現状を守ろうとする人々特有の、自己肯定感と不安の奇妙なミックスを示している。

RT編集者、ヘンリー・ジョンストン。金融業界で10年以上働き、FINRAシリーズ7およびシリーズ24の資格保持者。

ジャネット・イエレン米財務長官が、ウクライナのためにロシアが凍結している3000億ドルの外貨準備の差し押さえを求める西側政府高官たちの大合唱に、その声を加える最新の人物となった。これは、リシ・スナック英国首相が週末に寄稿した論説で、西側諸国が資産没収に向けて「より大胆に」動くよう呼びかけたことを受けたものだ。

欧州の一部では遠慮がちで、そのような行動はあからさまな違法行為であり、金融システムの完全性にも有害であるとの様々な忠告にもかかわらず、このアイデアは、特にワシントンとロンドンで独自の勢いを帯びているようだ。

私たちが目の当たりにしているのは、金融機関の健全性を維持するという約束よりも、短期的な利益を優先させようとする考え方の鮮明な例である。また、後述するように、これは重大な変化の時期に生じる、ある種の逆説的な衝動の現れでもある。

この場合、問題になっているのは欧米主導の世界金融システムであり、その中心にあるのは米ドルである。2022年2月にウクライナ紛争が始まった直後から固定化されているロシア中央銀行の外貨準備の明白な没収は、このシステムの信頼性に新たな衝撃を与えるだろう。資産の大半は実際にヨーロッパで保有されているため、誰が指示を出しているのか、誰の信用が危機に瀕しているのかについて、混乱は生じないだろう。

第二次世界大戦の末期に確立されたブレトンウッズの枠組み全体が、戦勝国米国の利益に大いに貢献したことは確かだ。しかし、何十年もの間、ドルは市場で決定される貿易の基準点であり通貨であるだけでなく、安全な価値の貯蔵場所として、地政学的な範囲で広く見なされていたことに異論はないだろう。貿易の自由化が進むにつれ、安全で信頼できるドルシステムという前提が、あらゆる経済・貿易政策に組み込まれるようになった。このような前提は、世界金融システムの構造そのものとなった。

ドルに関連するリスクが存在することが理解されていたとしても、それは主として金利政策の領域に横たわるもの、言い換えれば、システムそのものに内在するリスクではなく、市場リスクであると見なされていた。 1980年代から90年代にかけての一連の新興国危機は、多くの国々に過剰なドル債務の危険性と、米国の利上げがもたらす危険性について警告を与えた。

しかし、多くの国々がこれらのエピソードから導き出した結論のひとつは、ショックに対する防波堤としてドル準備をより多く保有する必要性であった。2000年から2005年にかけて、ドル金利の上昇に端を発した危機が20年間続いた直後、新興国市場は年間約2,500億ドル(GDP比3.5%)という記録的なペースでドル準備を積み増した。

言い換えれば、各国はドルの保有を増やすことで、ドルの領域から発せられるショックに対応したのである。このことは、当時のドル関連リスクのとらえ方の本質を浮き彫りにしている。ドルへのエクスポージャーの拡大がリスクになるとは誰も考えなかったのだ。システムの監督者と対立した場合、数千億ドル相当の準備金が没収されるかもしれないという考えは、どの方程式にもなかった。

近年のドルの武器化によって、これまで想像もしなかったようなリスクが発生した。ドルを使うことに政治的リスク・プレミアムが存在するようになったことは、通貨が何十年もの間どのように見られていたかをすでに大きく逸脱している。この結果はすでに誰の目にも明らかで、広範な脱ドルの流れがある。

しかし、おそらくもっと陰湿なのは、ロシアの埋蔵金奪取を主張する人々が、自由主義思想全体の基本原則を覆していることだ。これは、結果とプロセスを混同していると考えるのが妥当だろう。リベラルな社会、あるいは法治主義に基づくシステム(何と呼ぼうと勝手だが)は、すべての人が結果や政策に合意するからではなく、その結果や政策が実施される一連のプロセスやルールにコンセンサスがあるからこそ維持されるのである。 プロセスやルールは、特定の結果を保証するために存在するものではなく、実際には、そのルールを司る人々の利益と相反する結果を生むこともある。

ロシアの資産を没収する計画で私たちが目にしているのは、リベラルな秩序を守るために行われた行為(リベラルな価値観を踏みにじるロシアを罰し、リベラルな民主主義を目指すウクライナを支援する)として、望ましい結果が喧伝されていることだ。既存のプロセスの合理的な適用からは望ましい結果は生まれないので、求められているのは、それらのプロセスの根本的に異なる解釈である。西側当局者が資産を没収する「合法的な方法」を見つけようと呼びかけるとき、彼らが本当に意味しているのは、結果が最優先であり、どんな法的な見せかけでも構わないということだ。

わかりやすく言えば、リベラルな秩序はもはや、そのより深い原則に訴えることによってではなく、表面的にはリベラルな秩序の利益を促進するように見える結果を、たとえそれが明らかに非リベラルなアプローチによるものであったとしても、主張する努力によって守られているのである。

この極めて重要な区別が腐食するとき-今起きているように-、その課題は、より深い変化を、異なる結果という観点からではなく、結果を生み出すプロセスの変容という観点から見ることである。統計的なプロセス管理で考えてみるといい。そこでは、あるプロセスが仕様の範囲内にとどまっているのか、それとも何らかの変化を遂げたのかを判断しようとする。

© Getty Images / picture alliance / Contributor

20世紀のスペインの哲学者、ホセ・オルテガ・イ・ガセットは、西洋文明において、自分が受け継ぎ、主宰する制度を当然のものと考え、その恩恵を享受する一方で、これらの制度がどのようにして生まれたのか、制度を維持するために何をしなければならないのかについてほとんど考えない、ある種の人物が台頭してきたと述べている。オルテガはこのような人物を、甘やかされた子供や世襲貴族に例えた。自分が受け継いできたもののもろさを知らず、自分に自信過剰な彼は、必然的に自分に託された制度そのものの劣化を招いてしまう。

これが、現在の欧米の指導者たち、特にワシントンの指導者たちの本質である。第二次世界大戦直後の数十年間に生まれた彼らは、リベラルでルールに基づいた秩序と、その経済的翼であるドルを基盤とした金融システムの優位性を当然のこととしている。彼らはこの世界秩序について、畏敬の念やその根源に対する深い理解をもって語るのではなく、感情的に積まれた、しかし空虚な決まり文句で語る。リベラルな秩序から大きな恩恵を受けている一方で、それを支えているとされる実際の原則にはほとんど関心を示さない。彼らは常に自由主義秩序を口にするが、そのほとんどはさまざまな敵や敵対者を打ちのめすためである。

ブレット・スティーブンスによる『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙の最近の論説は、「バイデンはいかにしてナヴァルニーの仇を討つか」と題し、2021年にバイデンがロシアのプーチン大統領に行った、野党指導者が獄中で死亡した場合の「壊滅的な」結果についての警告を実行に移す可能性のある手段として、ロシアの凍結された3000億ドルの資金を差し押さえることを挙げている。

スティーブンスは、このような動きがドル離れを引き起こす可能性があるという懸念に触れているが、「ウクライナを救い、ロシアを罰する必要性がより緊急でなければ、このような議論は説得力を持つかもしれない」と結論づけている。言い換えれば、ステファンズが言うように、"米国の脅威が空虚なものではないことを独裁者に示すという戦略的要請 "を追求するという象徴的なジェスチャーの祭壇のために、米国が繁栄のために依存しているドルシステムそのものが犠牲になる可能性があるということだ。

リベラルなグローバル秩序の守護神であるジャネット・イエレンは、最近のコメントで、ロシアの外貨準備を押収することがシステムそのものにもたらす脅威を否定している。なぜなら「現実的に代替案がない」からである。イエレン議長にとって、このような動きは「米国では法的に許されない」という以前の見解から一転しての支持である。しかし、今や風向きは変わり、法的にはより有望視されているようだ。

支配階級の間には、このような無頓着さが蔓延している。王政の永続性を当然視する退位間近の国王のように、今日の指導者たちは、自分たちが支配する体制の真の基盤が何であるかを深く考えることができないのだ。

しかし、それ以外にも何かがある。それは、明らかに破綻しているウクライナの対ロシア代理戦争への資金が枯渇し、パニックに陥っていることだ。 言い換えれば、イエレン議長のような自信に満ちた口調とは裏腹に、この計画は力強いものではなかったということだ。ごく短期的な目的のために(3000億ドルで欧米のウクライナ・プロジェクトを救えるのかという疑問はさておき)、このような危険な手段を取ろうとする姿勢は、暖を取るための最後の手段として家具を燃やすようなもので、自暴自棄の臭いがする。

このように、ロシアの資産差し押さえを推し進める思考は、オルテガが語るような自己肯定感から来るものであると同時に、急増する不安から来るものであるとも言える。前者は、欧米の指導者たちが、自分たちが実際に弱体化させている制度の不滅性を明らかに信じているためであり、後者は、危機の連鎖に直面し、長期的なコストはともかく、その場しのぎの解決策を求めることにますます狂奔しているためである。

先に述べた結果とプロセスの逆転は、この本質的に分裂病的な考え方のもうひとつの現れである。システムはその完全性に対するこのような打撃に耐えられるという信念がある。資産が盗まれ、ルールが破壊されても、ドルは常にトップにある。しかし、プロセスを結果に従属させる行為そのものが、システムがもろすぎて望ましくない結果に耐えられないという恐れの反映なのだ。ロシアが3,000億ドルの外貨準備を保有し続けることが、自由主義秩序が生き残るにはあまりにも危険な結果だとすれば、事態はまずいことになる。

自己肯定感と深い不安という、一見相容れないこの2つの性質は、画期的な変化の時代に現状にしがみつこうとする権力者の間でしばしば共存している。傲慢で無知なルーマニアの指導者ニコライ・チャウシェスクが1989年にブカレストで大規模な集会を招集したのも、それが彼の最後の破滅を招いたのだ。歴史家は、傲慢で無知なジャネット・イエレンズとリシ・スナクスを、理解もコントロールもできなかった歴史的プロセスに巻き込まれたと振り返るかもしれない。

本コラムに記載された発言、見解、意見はあくまでも筆者のものであり、必ずしもRTのものを代表するものではない。

スペイン語訳:

1 Mar. 2024, 12:19

PortadaNoticias de empresa

Orden mundial esquizofrénico: Occidente está dispuesto a destruir su sistema financiero para castigar a Rusia

Los líderes occidentales actuales muestran una extraña mezcla de seguridad en sí mismos y ansiedad, característica de quienes defienden el statu quo en tiempos de cambios radicales.

Por Henry Johnston, redactor de RT. Trabajó durante más de una década en finanzas y es titular de las licencias FINRA Serie 7 y Serie 24.

La secretaria del Tesoro de EE.UU., Janet Yellen, ha sido la última en sumarse al creciente coro de funcionarios occidentales que piden la incautación de los 300.000 millones de dólares de reservas de divisas congeladas de Rusia en beneficio de Ucrania. Esto se produce después de que el primer ministro del Reino Unido, Rishi Sunak, escribiera un artículo de opinión el fin de semana en el que pedía a Occidente que fuera "más audaz" a la hora de avanzar hacia la confiscación de los activos.

A pesar de las reticencias mostradas en algunos sectores europeos y de las advertencias de que una acción de este tipo sería ilegal y perjudicial para la integridad del sistema financiero, la idea parece estar cobrando fuerza, sobre todo en Washington y Londres.

Lo que estamos viendo es un claro ejemplo del tipo de pensamiento que antepone los beneficios percibidos a corto plazo al compromiso de preservar la integridad de una institución que deriva su potencia precisamente de la confianza generalizada en esa integridad. También es, como veremos, una manifestación de un tipo particular de impulso paradójico que surge en épocas de cambios trascendentales.

En este caso, la institución en cuestión es el sistema financiero mundial dirigido por Occidente, en cuyo centro se encuentra el dólar estadounidense. La confiscación directa de las reservas del banco central ruso, inmovilizadas desde poco después de que comenzara el conflicto de Ucrania en febrero de 2022, asestaría otro duro golpe a la credibilidad de este sistema. Aunque la mayoría de los activos se encuentran en Europa, no habría confusión sobre quién lleva la voz cantante y de quién es la credibilidad en juego.

Por supuesto, las opiniones difieren sobre la integridad del sistema centrado en el dólar, y ciertamente todo el marco de Bretton Woods establecido en los últimos días de la Segunda Guerra Mundial sirvió en gran medida a los intereses de los victoriosos estadounidenses. Pero no se puede negar que durante décadas el dólar fue considerado en todo el espectro geopolítico no sólo como un punto de referencia determinado por el mercado y una moneda para el comercio, sino también como un depósito de valor seguro. A medida que el comercio se liberalizaba cada vez más, los supuestos sobre un sistema del dólar seguro y fiable se incorporaron a todo tipo de políticas económicas y comerciales. Estos supuestos se convirtieron en parte del tejido mismo del sistema financiero mundial.

Cuando se entendía que existían riesgos relacionados con el dólar, se consideraba que se encontraban en el ámbito de la política de tipos de interés; en otras palabras, se trataba de riesgos de mercado más que de riesgos inherentes al propio sistema. Una serie de crisis de los mercados emergentes en los años ochenta y noventa dejó a muchos países escarmentados sobre los peligros de una deuda excesiva en dólares y los peligros que pueden desencadenar las subidas de los tipos de interés estadounidenses.

Pero una de las conclusiones que muchos países sacaron de estos episodios fue la necesidad de mantener mayores reservas de dólares como baluarte contra las crisis. Entre 2000 y 2005, justo después de dos décadas de crisis desencadenadas a menudo por la subida de los tipos de interés en dólares, los mercados emergentes acumularon reservas en dólares a un ritmo récord de unos 250.000 millones de dólares anuales, o el 3,5% del PIB, un nivel cinco veces superior al de principios de los años noventa.

En otras palabras, los países respondieron a las perturbaciones procedentes del ámbito del dólar aumentando sus tenencias de dólares. Esto no hace sino subrayar la naturaleza de cómo se percibía entonces el riesgo relacionado con el dólar. A nadie se le ocurría que una mayor exposición al dólar fuera en sí misma un riesgo. La idea de que cientos de miles de millones de dólares en reservas podían ser confiscados si un país se encontraba en desacuerdo con los supervisores del sistema no entraba en ninguna de las ecuaciones.

La militarización del dólar en los últimos años ha introducido una fuente de riesgo hasta ahora inimaginable. El hecho de que ahora exista una prima de riesgo político por utilizar el dólar es ya una grave desviación de la visión que se tuvo de la moneda durante décadas. Las consecuencias ya son evidentes para todos - la tendencia generalizada a la desdolarización - aunque muchos en los pasillos del poder occidental sigan ignorando lo que está sucediendo.

Pero quizás aún más insidioso es que quienes abogan por la incautación de las reservas rusas han puesto patas arriba un principio fundamental de toda la idea liberal. La mejor forma de entenderlo es como una fusión de resultados y procesos. Una sociedad liberal o un sistema basado en el Estado de Derecho -llámese como se quiera- se mantiene unido no porque todos estén de acuerdo en los resultados y las políticas, sino porque existe un consenso sobre el conjunto de procesos y normas mediante los cuales se aplican esos resultados y políticas. Los procesos y las normas no existen para garantizar unos resultados determinados y, de hecho, pueden producir resultados contrarios a los intereses de quienes presiden esas normas.

Con el plan para confiscar los activos rusos, lo que estamos viendo es un resultado deseado que se anuncia a bombo y platillo como un acto realizado en defensa del orden liberal (castigar a la Rusia que pisotea los valores liberales y apoyar a la Ucrania aspirante a la democracia liberal), mientras que la integridad de los procesos es ahora totalmente secundaria. Dado que el resultado deseado no surge de ninguna aplicación razonable de los procesos existentes, lo que se busca es una interpretación radicalmente distinta de esos procesos. Cuando los funcionarios occidentales piden que se encuentre "una manera legal" de confiscar los activos, lo que realmente quieren decir es que el resultado es primordial y que cualquier hoja de parra legal servirá.

Por decirlo claramente, el orden liberal ya no se defiende apelando a sus principios más profundos, sino abogando por resultados que superficialmente parecen promover sus intereses, aunque esos resultados surjan de un enfoque claramente antiliberal.

Cuando esta distinción extremadamente crítica sufre una corrosión -como está ocurriendo ahora-, el reto consiste en ver el cambio profundo no en términos de un resultado diferente, sino en términos de una transformación de los procesos que producen el resultado. Para los frikis de la estadística, piénselo en términos de control estadístico de procesos, donde se intenta determinar si un proceso se ha mantenido dentro de las especificaciones o ha sufrido algún tipo de cambio.

RT

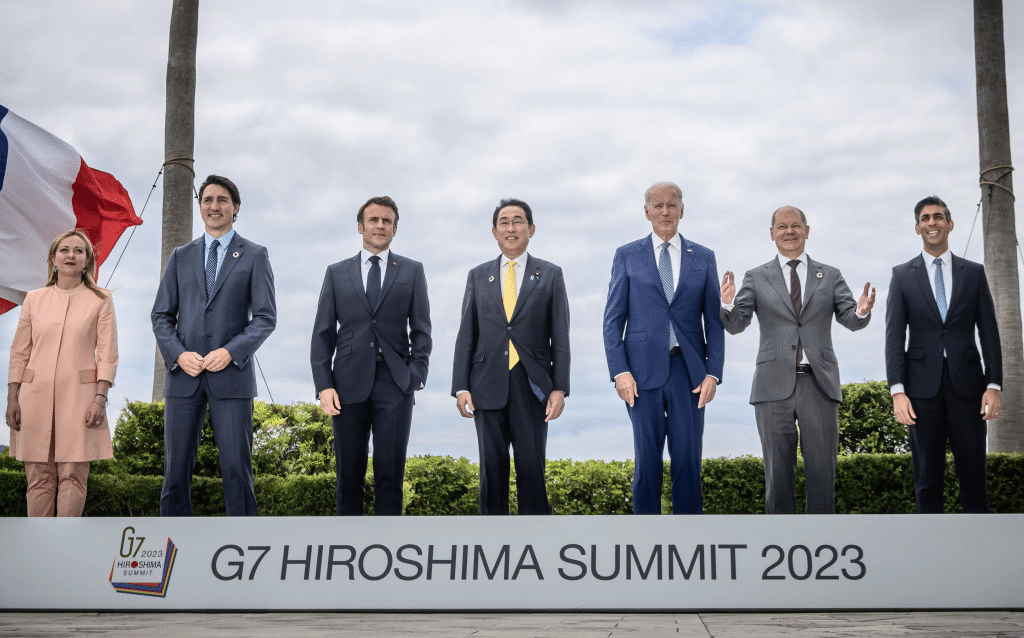

Los líderes del G7 posan para una foto de grupo durante la Cumbre del G7 en el Grand Prince Hotel en Hiroshima, Japón, 20 de mayo de 2023. © Getty Images / picture alliance / Colaborador

El filósofo español del siglo XX José Ortega y Gasset describió el ascenso a la prominencia en la civilización occidental de un cierto tipo de persona que da por sentadas las instituciones que ha heredado y preside, disfrutando de sus beneficios mientras apenas piensa en cómo surgieron esas instituciones y qué hay que hacer para mantenerlas. Ortega lo comparaba con un niño mimado o un aristócrata hereditario. Ignorante de la fragilidad de su herencia y sumamente confiado en sí mismo, provoca inevitablemente la degradación de las propias instituciones que le han sido confiadas.

Tal es la esencia de la actual cosecha de líderes occidentales, especialmente los de Washington. Nacidos en su mayoría en las décadas inmediatamente posteriores a la Segunda Guerra Mundial, dan por sentada la supremacía del orden liberal basado en normas y su ala económica, el sistema financiero basado en el dólar. Hablan de este orden mundial no con reverencia y un profundo conocimiento de sus raíces, sino con clichés emocionalmente cargados pero vacuos. Aunque se benefician enormemente del orden liberal, muestran poco interés por los principios reales que pretenden sustentarlo. Lo invocan constantemente, pero sobre todo para aporrear a diversos enemigos y adversarios.

Un reciente artículo de opinión de Bret Stephens en el New York Times titulado "Cómo Biden puede vengar la muerte de Navalny" enumeraba la incautación de los 300.000 millones de dólares en fondos congelados de Rusia como una posible vía para cumplir la advertencia que Biden hizo al presidente ruso Vladimir Putin en 2021 sobre las "devastadoras" consecuencias en caso de que el líder de la oposición muriera en prisión.

Stephens menciona la preocupación de que una medida así pudiera desencadenar una huida del dólar, pero concluye que ese argumento "podría ser persuasivo si la necesidad de salvar a Ucrania y castigar a Rusia no fuera más urgente". En otras palabras, el propio sistema del dólar en el que se basa Estados Unidos para lo que queda de su prosperidad puede sacrificarse en el altar del gesto simbólico de, como dice Stephens, perseguir "el imperativo estratégico de demostrar a un dictador que las amenazas estadounidenses no son huecas".

Janet Yellen, paladín del orden mundial liberal donde los haya, se mostró desdeñosa en recientes comentarios sobre las amenazas que la incautación de las reservas rusas supondría para el propio sistema. Es "extremadamente improbable" que la intervención de los fondos perjudique la posición del dólar porque "siendo realistas, no hay alternativas", opina. Para Yellen, su apoyo supone un giro respecto a su anterior opinión de que tal medida "no era legalmente permisible en Estados Unidos". Pero ahora los vientos han cambiado y el caso legal parece más prometedor.

Tal es la despreocupación reinante entre la clase dirigente. Al igual que un rey a punto de ser depuesto que da por sentada la permanencia de la monarquía, los líderes actuales simplemente no pueden contemplar en profundidad lo que constituye el verdadero fundamento del sistema que presiden.

Pero hay algo más en juego. Conviene recordar qué es lo que ha animado el debate sobre la confiscación de activos rusos en las últimas semanas: el pánico a que se agote la financiación de la claramente fracasada guerra de Ucrania contra Rusia. En otras palabras, a pesar de los tonos seguros de sí mismos de Yellen, el plan no ha surgido de un lugar de fortaleza. La voluntad de dar un paso tan peligroso por objetivos a muy corto plazo (dejando a un lado la cuestión de si 300.000 millones de dólares pueden salvar el proyecto de Occidente en Ucrania) puede verse como algo parecido a quemar los muebles como último recurso para mantenerse caliente: apesta a desesperación.

Así pues, podemos afirmar que el tipo de pensamiento que impulsa la presión para apoderarse de los activos rusos deriva de la seguridad en sí mismo de la que habla Ortega, pero también de una creciente ansiedad. La primera se debe a la aparente creencia de los líderes occidentales en la indestructibilidad de las instituciones que en realidad están socavando; la segunda, a que se enfrentan a una cascada de crisis y cada vez buscan con más frenesí soluciones provisionales a cualquier coste a largo plazo.

La inversión de resultados y procesos de la que hablábamos antes es otra manifestación de esta mentalidad esencialmente esquizofrénica. Existe la creencia de que el sistema puede resistir tales golpes a su integridad: los activos pueden ser robados y las reglas subvertidas, pero el dólar siempre estará en la cima. Y, sin embargo, el acto de subordinar los procesos a los resultados es en sí mismo un reflejo del temor a que el sistema sea demasiado frágil para resistir resultados indeseables. Si la retención por parte de Rusia de sus 300.000 millones de dólares en reservas es un resultado demasiado peligroso para que el orden liberal sobreviva, entonces las cosas van mal.

Estos dos rasgos aparentemente irreconciliables -seguridad en sí mismos y profunda ansiedad- coexisten a menudo entre quienes ocupan posiciones de poder y tratan de aferrarse al statu quo en tiempos de cambio trascendental. Es lo que llevó al arrogante y despistado líder rumano Nicolae Ceausescu a convocar un gran mitin en Bucarest en 1989 que acabaría siendo su perdición final. Es muy posible que los historiadores recuerden a los arrogantes y despistados Janet Yellens y Rishi Sunaks como atrapados en procesos históricos que no podían comprender ni controlar.

Las declaraciones, opiniones y puntos de vista expresados en esta columna son exclusivamente los del autor y no representan necesariamente los de RT.

原文:

1 Mar. 2024, 12:19

HomeBusiness News

Schizophrenic world order: The West is willing to destroy its financial system to punish Russia

Today’s Western leaders exhibit a strange mix of self-assuredness and anxiety that’s characteristic of those defending the status quo during times of sweeping change

By Henry Johnston, an RT editor. He worked for over a decade in finance and is a FINRA Series 7 and Series 24 license holder.

US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has become the latest to add her voice to the growing chorus of Western officials calling for the seizure of Russia’s $300 billion in frozen foreign-exchange reserves for the benefit of Ukraine. This comes after UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak penned an op-ed over the weekend in which he called for the West to be “bolder” in moving toward confiscating the assets.

Notwithstanding the reticence being displayed in some quarters of Europe and various admonitions that such an action would be both blatantly illegal and also detrimental to the integrity of the financial system, the idea seems to be taking on a momentum of its own, particularly in Washington and London.

What we are seeing is a vivid example of the type of thinking that places perceived short-term gains ahead of a commitment to preserve the integrity of an institution that derives its potency precisely from widespread confidence in that integrity. It is also, as we will see, a manifestation of a particular type of paradoxical impulse that arises during times of momentous change.

In this case, the institution in question is the Western-led global financial system, at the very heart of which is the US dollar. Outright confiscation of the Russian central bank reserves that have been immobilized since shortly after the Ukraine conflict began in February 2022 would deliver another jolting blow to the credibility of this system. Even as most of the assets are actually held in Europe, there would be no confusion about who was calling the shots and whose credibility is on the line.

Of course, views differ about how much integrity the dollar-centric system ever had, and certainly the entire Bretton Woods framework established in the waning days of World War II very much served the interests of the victorious Americans. But it cannot be disputed that for decades the dollar was widely viewed across the geopolitical spectrum as not just a market-determined reference point and currency for trade but as a safe store of value. As trade became increasingly liberalized, assumptions about a safe and dependable dollar system were built into all manner of economic and trade policies. Such assumptions became part of the very fabric of the global financial system.

Where risks related to the dollar were understood to exist, they were largely seen as lying in the realm of interest-rate policy – in other words, these were market risks rather than risks inherent to the system itself. A series of emerging-market crises in the 1980s and ‘90s left many countries chastened about the perils of excessive dollar debt and the dangers that US interest-rate hikes can unleash.

But one of the conclusions that many countries drew from these episodes was the necessity of holding greater dollar reserves as a bulwark against shocks. Between 2000 and 2005, right on the heels of two decades of crises often triggered by rising dollar interest rates, emerging markets actually accumulated dollar reserves at a record pace of about $250 billion per annum, or 3.5% of GDP – a level five times higher than in the early 1990s.

In other words, countries responded to shocks emanating from the dollar realm by increasing holdings of dollars. This only underscores the nature of how dollar-related risk was perceived at the time. It simply didn’t occur to anybody that greater exposure to the dollar was itself a risk. The idea that hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of reserves could simply be confiscated if a country found itself at odds with the overseers of the system didn’t factor into any of the equations.

The weaponization of the dollar in recent years has introduced a heretofore unimagined source of risk. That there is now a political risk premium to using the dollar is already a serious deviation from how the currency was viewed for decades. The consequences of this are already apparent for all to see – the widespread de-dollarization trend – although many in the halls of Western power remain dismissive about what is happening.

But perhaps even more insidious is that those advocating for the seizure of Russia’s reserves have turned on its head a fundamental principle of the entire liberal idea. This is best thought of as a conflation of outcomes and processes. A liberal society or rule-of-law-based system – call it what you want – is held together not because all agree on outcomes and policies, but because there is a consensus on the set of processes and rules by which those outcomes and policies are implemented. The processes and rules do not exist to ensure particular outcomes and, in fact, may produce outcomes that are at odds with the interests of those who preside over those rules.

With the plan to confiscate the Russian assets, what we are seeing is a desired outcome being trumpeted as an act done in defense of the liberal order (punish the liberal-values-stomping Russia and support the liberal-democracy aspirant Ukraine), whereas the integrity of the processes is now entirely secondary. Since the desired outcome does not emerge from any reasonable application of existing processes, what is being sought is a radically different interpretation of those processes. When Western officials call for finding “a legal way” to confiscate the assets, what they really mean is that the outcome is paramount and that any legal fig leaf will do.

To put it plainly, the liberal order is no longer being defended by an appeal to its deeper principles but by efforts to advocate outcomes that superficially seem to advance its interests – even if those outcomes emerge from a distinctly illiberal approach.

When this extremely critical distinction undergoes corrosion – as is happening now – the challenge is to see the deeper change not in terms of a different outcome but in terms of a transformation of the processes that produce the outcome. For quant geeks, think of it in terms of statistical process control, where one tries to determine whether or not a process has remained within specs or has undergone some sort of shift.

RT

The G7 leaders pose for a group photo during the G7 Summit at the Grand Prince Hotel in Hiroshima, Japan, May 20, 2023. © Getty Images / picture alliance / Contributor

The 20th century Spanish philosopher Jose Ortega y Gasset described the rise to prominence in Western civilization of a certain type of person who takes for granted the institutions he has inherited and presides over, enjoying their benefits while giving scarce thought to how these institutions arose and what must be done to maintain them. Ortega likened such a person to a spoiled child or a hereditary aristocrat. Ignorant of the fragility of his inheritance and supremely confident in himself, he inevitably ushers in a degradation of the very institutions he has been entrusted with.

Such is the essence of the current crop of Western leaders, particularly those in Washington. Born mostly in the decades immediately following World War II, they take as a given the supremacy of the liberal, rules-based order and its economic wing – the dollar-based financial system. They speak of this world order not with reverence and a deep understanding of its roots but in emotionally laded yet vacuous cliches. While benefitting themselves greatly from the liberal order, they show little interest in the actual principles that purport to underpin it. They invoke it constantly, but mostly in order to bludgeon various foes and adversaries.

A recent op-ed in the New York Times by Bret Stephens titled ‘How Biden Can Avenge Navalny’s Death’ listed seizing Russia’s $300 billion in frozen funds as a potential avenue for making good on a warning Biden gave to Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2021 of “devastating” consequences should the opposition leader die in prison.

Stephens does mention concerns that such a move could trigger flight from the dollar, but concludes that such an argument “might otherwise be persuasive if the need to save Ukraine and punish Russia weren’t more urgent.” In other words, the very dollar system that the US relies on for what’s left of its prosperity can be sacrificed at the altar of the symbolic gesture of, as Stephens puts it, pursuing “the strategic imperative of demonstrating to a dictator that American threats aren’t hollow.”

Janet Yellen, a paladin of the liberal global order if there ever was one, was dismissive in recent comments of the threats that seizing Russia’s reserves would pose to the system itself. It is “extremely unlikely” that tapping the funds would harm the dollar’s standing because “realistically there are no alternatives,” she believes. For Yellen, her support marks an about-face from her earlier view that such a move was “not legally permissible in the United States.” But the winds have now changed and the legal case is apparently looking more promising.

Such is the prevailing insouciance among the ruling class. Like a soon-to-be-deposed king who takes for granted the permanence of the monarchy, today’s leaders simply cannot contemplate at any depth what constitutes the true foundation of the system they preside over.

But there is something else at play. It bears recalling what has animated the discussion of seizing Russia’s assets in recent weeks in the first place: it is the panic setting in over the drying up of funding for the clearly failing Ukraine proxy war against Russia. In other words, notwithstanding the self-assured tones from the likes of Yellen, the plan has not emerged from a place of strength. The willingness to take such a dangerous step for very short-term aims (putting aside the question of whether $300 billion can even save the West’s Ukraine project) can be seen as akin to burning the furniture as a last resort to stay warm – it reeks of desperation.

Thus we can say that the type of thinking driving the push to seize the Russian assets derives from the self-assuredness about which Ortega speaks but also from a burgeoning anxiety. The former is due to Western leaders’ apparent belief in the indestructability of the institutions that they are actually undermining; the latter because they are facing a cascade of crises and are increasingly frantic in seeking stopgap solutions at whatever long-term cost.

The inversion of outcomes and processes that we spoke of earlier is another manifestation of this essentially schizophrenic mindset. There is a belief that the system can withstand such blows to its integrity: assets can be stolen and rules subverted but the dollar will always be on top. And yet the act of subordinating processes to outcomes is itself a reflection of a fear that the system is too fragile to withstand undesirable outcomes. If Russia retaining possession of its $300 billion in reserves is an outcome too dangerous for the liberal order to survive, then things are in bad shape.

These two seemingly irreconcilable traits – self-assuredness and deep anxiety – are often found coexisting among those in positions of power who are trying to cling on to the status quo during times of epochal change. It is what drove the arrogant and clueless Romanian leader Nicolae Ceausescu to call a large rally in Bucharest in 1989 that would prove to be his final undoing. Historians may very well look back at the arrogant and clueless Janet Yellens and Rishi Sunaks as caught up in historical processes that they could neither comprehend nor control.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?