ドミトリー・トレニン:ロシアでは大規模な変革が起きているが、西側諸国はそれに気づいていない

2024年 5月 13日 12:55

ホームロシア・ロシア連邦

ドミトリー・トレニン:ロシアでは大規模な変革が起きているが、西側諸国はそれに気づいていない

2022年初頭にウクライナで戦闘が勃発する前に始まったロシア社会の変革は、今や不可逆的なものに思える。

ドミトリー・トレニン(高等経済学院教授、世界経済・国際関係研究所主任研究員)著。ロシア国際問題評議会(RIAC)のメンバーでもある。

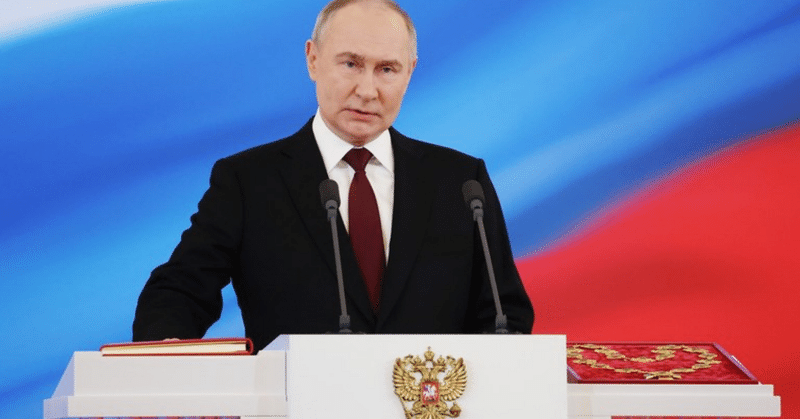

写真上: ロシア、モスクワのクレムリンで行われた就任式で宣誓するプーチン大統領。© Sputnik / Vyacheslav Prokofyev

ウクライナでの西側諸国との戦争から2年半が経過し、ロシアは確実に新たな自己認識の方向に向かっている。

この傾向は実際には軍事作戦以前からあったが、結果として強力に強まっている。2022年2月以来、ロシア人はまったく新しい現実の中に生きている。1945年以来初めて、この国は本当に戦争状態にあり、2,000キロに及ぶ前線で、モスクワからさほど遠くない場所で激しい戦闘が続いている。ウクライナ国境に近い地方都市ベルゴロドは、キエフ軍からの致命的なミサイル攻撃やドローン攻撃を受け続けている。

時には、ウクライナの無人偵察機がはるか内陸部まで到達することもある。しかし、モスクワやその他の大都市は、まるで戦争がなかったかのように、そして(ほとんど)西側の制裁もなかったかのように続いている。通りは人で溢れ、ショッピングモールやスーパーマーケットでは、いつものように豊富な商品や食料品が並んでいる。モスクワとベルゴロドは2つの国の物語であり、ロシア人は戦時と平時の両方を同時に生きることができたと結論づけることもできる。

これは間違った結論だろう。表向き「平和に」暮らしている部分ですら、ウクライナ紛争が始まる前とは明らかに異なっている。ポスト・ソビエト・ロシアの中心であった「お金」は、もちろんなくなったわけではないが、疑いようのない支配力を失ったことは確かだ。兵士だけでなく一般市民も含め、多くの人々が殺されているとき、他の非物質的な価値観が復活しつつある。ソビエト連邦の崩壊をきっかけに非難され、嘲笑された愛国心が、再び力強く台頭してきている。新たな動員がない中、軍と契約する何十万人もの人々は、国を助けたいという願望に突き動かされている。軍から得られるものだけではない。

ロシアの大衆文化は、西側で流行しているものを模倣する習慣を、ゆっくりと、しかし着実に捨てつつある。その代わりに、詩、映画、音楽などロシア文学の伝統が復活し、発展している。国内観光の急増は、普通のロシア人に自国の宝物を開放している。(海外旅行はまだ可能だが、物流が困難なため、ヨーロッパの他の地域へのアクセスは以前よりはるかに不便になっている)。

政治的には、現体制に反対する声はない。かつての指導者たちはほとんど海外におり、アレクセイ・ナヴァルニーは獄死した。2022年2月以降、イスラエルや西ヨーロッパなどへの移住を決めた多くのかつての文化的アイコンは、国が進むにつれ、急速に昨日の有名人になりつつある。遠くからロシアを批判するロシアのジャーナリストや活動家たちは、ますます以前の聴衆との接点を失い、ウクライナの代理戦争でロシアと戦う国々の利益に奉仕しているという非難を浴びている。対照的に、動員を恐れて2022年にロシアを離れた若者の3分の2近くが戻ってきており、そのうちの何人かは海外での経験にかなり傷ついている。

新たな国家エリートの必要性に関するプーチンの発言と、そのエリートの中核として戦争帰還兵を推すことは、現段階では実際の計画というより意図的なものだが、ロシアのエリートは間違いなく大規模な入れ替わりを経験している。リベラル派の大物の多くは、本質的にもはやロシアに属していない。西側に資産を維持しようとする彼らの欲望は、結果的に彼らを祖国から引き離すことになった。

ロシアに留まった人々は、地中海のヨットやコートダジュールの別荘、ロンドンの豪邸がもはや手に入らないこと、少なくとも安全に保管できないことを知っている。ロシア国内では、中堅ビジネスパーソンの新しいモデルが生まれつつある。それは、(ESGモデルではなく)社会的関与と金銭を結びつけ、国内で自分の将来を築く人である。

ロシアの政治文化は基本に戻りつつある。西欧のそれとは異なり、東洋にいくらか似ているが、それは家族のモデルに基づいている。秩序があり、ヒエラルキーがあり、権利と責任のバランスが保たれ、国家は必要悪ではなく、主要な公共財であり、社会の最重要価値である。その代わり、国家の舵取りを任された者は、仲裁を行い、さまざまな利害の調和を図ることなどが期待される。もちろん、これは現実よりもむしろ理想である。現実はもっと複雑怪奇だが、伝統的な政治文化はその核心において健在であり、この30~40年間は、大いに示唆に富み衝撃的ではあったが、それを覆すものではなかった。

西側に対するロシアの態度も複雑だ。西洋の古典文化や近代文化(ポストモダンはそうでもないが)、芸術や技術、生活水準はある程度評価されている。最近では、LGBTQの価値観やキャンセル・カルチャーの積極的な推進などによって、西欧社会に対する以前までの純粋な肯定的イメージが損なわれている。また、欧米の政策や政治、特に政治家に対する見方も変わってきており、多くのロシア人がかつて抱いていた尊敬の念を失っている。クレムリンのプロパガンダが主な理由ではなく、ウクライナにロシア兵や民間人を殺す武器を提供したり、様々な意味で無差別な制裁を行ったり、ロシア文化を取りやめようとしたり、ロシア人を世界のスポーツ界から締め出そうとするなど、西側諸国自身の政策が影響しているのだ。その結果、ロシア人が個々の欧米人を敵視するようになったわけではないが、政治的/メディア的な欧米は敵対者の家として広く見られている。

「われわれは何者か」、「われわれはこの世界のどこにいるのか」、「われわれはどこへ行こうとしているのか」についての一連の指針となる思想が必要なのは明らかだ。しかし、「イデオロギー」という言葉は、多くの人々の心の中で、ソ連のマルクス・レーニン主義の硬直性とあまりにも密接に結びついている。最終的に出てくるものは、おそらくロシア正教をはじめとする伝統的な宗教の価値観主導の土台の上に築かれ、ペトリン時代以前、帝国時代、ソ連時代など、私たちの過去の要素を含むものになるだろう。西側との現在の対立は、主権と愛国心、法と正義が中心的な役割を果たす、ある種の新しいイデオロギー的概念を最終的に出現させることを不可欠にしている。西側のプロパガンダはそれを "プーチニズム "と侮蔑的に呼ぶが、ほとんどのロシア人にとって、それは単に "ロシアのやり方 "と言えるかもしれない。

もちろん、ある種の機会を奪った政策に不満を持つ人々もいる。特に、その人たちの関心がお金や個人の富にある場合はなおさらだ。海外に出て行っていないこのグループの人々は、静かに座り、不安を抱き、内心では、他の人々がどんな犠牲を払っても、何とかして「古き良き時代」が戻ってくることを願っている。彼らは失望するだろう。エリート内部の変化については、プーチンは体制に新鮮な血と活力を注入することを目指している。

ある種の「粛清」が起こるようには見えない。とはいえ、年齢的な要素を考えれば、変化はかなりのものになるだろう。現在のトップクラスの現職のほとんどは70代前半だ。今後6年から10年のうちに、これらの地位は若い人たちに移るだろう。プーチンの遺産を存続させることは、クレムリンにとって大きな課題である。後継者問題とは、単に誰がトップに立つかという問題ではなく、どのような「支配世代」が登場するかという問題である。

スペイン語訳:

13 Mayo, 2024 12:55

PortadaRusia y FSU

Dmitry Trenin: En Rusia se está produciendo una transformación masiva, y Occidente no la ve

La transformación de la sociedad rusa, que comenzó antes de que estallaran los combates en Ucrania a principios de 2022, parece ahora irreversible.

Por Dmitry Trenin, profesor investigador de la Escuela Superior de Economía e investigador principal del Instituto de Economía Mundial y Relaciones Internacionales. También es miembro del Consejo Ruso de Asuntos Internacionales (RIAC).

Foto superior: El presidente ruso Vladimir Putin jura su cargo durante la ceremonia de investidura en el Kremlin de Moscú, Rusia. © Sputnik / Vyacheslav Prokofyev

Dos años y medio después de su guerra contra Occidente en Ucrania, Rusia se encuentra, sin duda, en el camino hacia un nuevo sentido de sí misma.

En realidad, esta tendencia es anterior a la operación militar, pero se ha intensificado poderosamente como consecuencia de ella. Desde febrero de 2022, los rusos viven en una realidad totalmente nueva. Por primera vez desde 1945, el país está realmente en guerra, con encarnizados combates a lo largo de una línea del frente de 2.000 kilómetros, y no demasiado lejos de Moscú. Belgorod, un centro provincial cercano a la frontera ucraniana, es continuamente objeto de mortíferos ataques con misiles y drones por parte de las fuerzas de Kiev.

En ocasiones, los drones ucranianos llegan mucho más al interior. Sin embargo, Moscú y otras grandes ciudades continúan como si no hubiera guerra, y (casi) tampoco sanciones occidentales. Las calles están llenas de gente y los centros comerciales y supermercados ofrecen la habitual abundancia de productos y alimentos. Se podría concluir que Moscú y Belgorod son una historia de dos países, que los rusos han conseguido vivir simultáneamente en tiempos de guerra y en tiempos de paz.

Sería una conclusión errónea. Incluso la parte del país que aparentemente vive "en paz" es notablemente diferente de lo que era antes de que comenzara el conflicto de Ucrania. El foco central de la Rusia postsoviética -el dinero- no ha sido eliminado, por supuesto, pero sin duda ha perdido su incuestionable dominio. Cuando mucha gente -no sólo soldados, sino también civiles- está siendo asesinada, otros valores no materiales están volviendo. El patriotismo, denostado y ridiculizado tras el colapso de la Unión Soviética, resurge con fuerza. A falta de una nueva movilización, cientos de miles de los que firman contratos con el ejército están motivados por el deseo de ayudar al país. No sólo por lo que puedan obtener de él.

La cultura popular rusa se está despojando -lentamente, quizá, pero con paso firme- del hábito de imitar lo que está de moda en Occidente. En su lugar, se están recuperando y desarrollando las tradiciones de la literatura rusa, incluidas la poesía, el cine y la música. El auge del turismo nacional ha abierto a los rusos de a pie los tesoros de su propio país, hasta hace poco desatendidos por la sed de viajar al extranjero. (Todavía se puede viajar al extranjero, pero la difícil logística hace que llegar a otras partes de Europa sea mucho menos fácil que antes).

Políticamente, no hay oposición que oponer al sistema actual. Casi todas sus antiguas figuras están en el extranjero, y Alexey Navalny ha muerto en prisión. Muchos antiguos iconos culturales que, después de febrero de 2022, decidieron emigrar a Israel, Europa Occidental u otros lugares, se están convirtiendo rápidamente en celebridades de ayer, a medida que el país avanza. Los periodistas y activistas rusos que critican a Rusia desde lejos están perdiendo cada vez más contacto con su público anterior, y cargan con acusaciones de servir a los intereses de los países que luchan contra Rusia en la guerra por poderes en Ucrania. Por el contrario, casi dos tercios de los jóvenes que abandonaron Rusia en 2022 por miedo a ser movilizados han regresado, algunos de ellos bastante amargados por su experiencia en el extranjero.

La declaración de Putin sobre la necesidad de una nueva élite nacional, y su promoción de los veteranos de guerra como el núcleo de esa élite, es más una intención que un plan real en esta etapa, pero la élite rusa está definitivamente pasando por un cambio masivo. Muchos magnates liberales esencialmente ya no pertenecen a Rusia; su deseo de mantener sus activos en Occidente ha terminado por separarlos de su país natal.

Los que se quedaron en Rusia saben que los yates en el Mediterráneo, las villas en la Costa Azul y las mansiones en Londres ya no están a su disposición, o al menos ya no es seguro que las conserven. En Rusia está surgiendo un nuevo modelo de empresario de nivel medio: el que combina el dinero con el compromiso social (no el modelo ESG), y que construye su futuro dentro del país.

La cultura política rusa está volviendo a sus fundamentos. A diferencia de la occidental, pero algo similar a la oriental, se basa en el modelo de una familia. Hay orden y jerarquía; los derechos están equilibrados por las responsabilidades; el Estado no es un mal necesario, sino el principal bien público y el máximo valor social. La política, en el sentido occidental de una competición constante y a menudo sin cuartel, se considera interesada y destructiva; en cambio, se espera que los encargados de llevar el timón del Estado arbitren, garanticen la armonía de los diversos intereses, etc. Por supuesto, esto es más un ideal que una realidad. En la realidad, las cosas son más complejas y complicadas, pero la cultura política tradicional, en su núcleo, está viva y coleando, y los últimos 30 o 40 años, aunque enormemente instructivos e impactantes, no la han trastocado.

Las actitudes rusas hacia Occidente también son complejas. Se aprecia la cultura occidental clásica y moderna (pero no tanto la posmoderna), las artes y la tecnología, y hasta cierto punto el nivel de vida. En los últimos tiempos, la imagen positiva de Occidente como sociedad se ha visto empañada por la agresiva promoción de los valores LGBTQ, de la cultura de la cancelación y cosas por el estilo. Lo que también ha cambiado es la visión de las políticas, la política y, sobre todo, los políticos occidentales, que han perdido el respeto que la mayoría de los rusos les tenían antaño. La visión de Occidente como adversario hereditario de Rusia ha vuelto a ganar protagonismo, no principalmente por la propaganda del Kremlin, sino en función de las propias políticas de Occidente, desde el suministro a Ucrania de armas que matan a soldados y civiles rusos, a las sanciones que en muchos aspectos son indiscriminadas, pasando por los intentos de cancelar la cultura rusa o de vetar a los rusos en los deportes mundiales. Esto no ha dado lugar a que los rusos vean a los occidentales individuales como enemigos, pero el Occidente político/mediático es ampliamente visto aquí como una casa de adversarios.

Hay una clara necesidad de un conjunto de ideas rectoras sobre "quiénes somos", "dónde estamos en este mundo" y "hacia dónde vamos". Sin embargo, la palabra "ideología" está demasiado ligada en la mente de mucha gente a la rigidez del marxismo-leninismo soviético. Lo que surja finalmente se construirá probablemente sobre los cimientos basados en valores de las religiones tradicionales, empezando por la ortodoxia rusa, e incluirá elementos de nuestro pasado, incluidos los periodos pre-petrino, imperial y soviético. La actual confrontación con Occidente hace imperativo que surja finalmente algún tipo de nuevo concepto ideológico, en el que la soberanía y el patriotismo, el derecho y la justicia ocupen un lugar central. La propaganda occidental lo denomina peyorativamente "putinismo" pero, para la mayoría de los rusos, puede describirse simplemente como "a la manera de Rusia".

Por supuesto, hay personas descontentas con políticas que les han privado de ciertas oportunidades. Sobre todo si los intereses de esas personas se centran en gran medida en el dinero y la riqueza individual. Los miembros de este grupo que no han salido al extranjero están tranquilos, albergan recelos y esperan en privado que, de algún modo, cueste lo que cueste a los demás, vuelvan los "buenos viejos tiempos". Es probable que se sientan decepcionados. En cuanto a los cambios dentro de la élite, Putin pretende infundir sangre fresca y vigor al sistema.

No parece que vaya a producirse una especie de "purga". Los cambios, no obstante, serán sustanciales, dado el factor edad. La mayoría de los actuales titulares de los puestos más altos rondan los 70 años. En los próximos seis a diez años estos puestos pasarán a manos de gente más joven. Garantizar que el legado de Putin perdure es una de las principales tareas del Kremlin. La sucesión no es sólo una cuestión de quién ocupa finalmente el puesto más alto, sino de qué tipo de "generación gobernante" llega.

原文:

13 May, 2024 12:55

HomeRussia & FSU

Dmitry Trenin: A massive transformation is taking place in Russia, and the West is blind to it

A societal transformation in Russia that started before fighting broke out in Ukraine in early 2022 now seems irreversible

By Dmitry Trenin, a research professor at the Higher School of Economics and a lead research fellow at the Institute of World Economy and International Relations. He is also a member of the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC).

Photo top: Russian President Vladimir Putin takes the oath of office during his inauguration ceremony at the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia. © Sputnik / Vyacheslav Prokofyev

Two and a half years into its war against the West in Ukraine, Russia certainly finds itself on a course toward a new sense of itself.

This trend actually predated the military operation but has been powerfully intensified as a result. Since February 2022, Russians have lived in a wholly new reality. For the first time since 1945, the country is really at war, with bitter fighting ongoing along a 2,000-kilometer front line, and not too far from Moscow. Belgorod, a provincial center near the Ukrainian border, is continuously subjected to deadly missile and drone attacks from Kiev's forces.

Occasionally, Ukrainian drones reach far deeper inland. Yet, Moscow and other big cities continue as if there were no war, and (almost) no Western sanctions either. Streets are full of people and shopping malls and supermarkets offer the usual abundance of goods and food items. One could conclude that Moscow and Belgorod are a tale of two countries, that Russians have managed to live simultaneously both in wartime and peacetime.

This would be a wrong conclusion. Even the part of the country that ostensibly lives ‘in peace’ is markedly different from what it was before the Ukraine conflict began. The central focus of post-Soviet Russia – money - has not been eliminated, of course, but has certainly lost its unquestionable dominance. When many people – not only soldiers but civilians, too – are getting killed, other, non-material values are coming back. Patriotism, reviled and derided in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, is re-emerging in force. In the absence of fresh mobilization, hundreds of thousands of those who sign contracts with the military are motivated by a desire to help the country. Not just by what they can get from it.

Russian popular culture is shedding – slowly, perhaps, but steadily – the habit of imitating what’s hot in the West. Instead, the traditions of Russian literature, including poetry, film, music are being revived and developed. A spike in domestic tourism has opened to ordinary Russians the treasures of their own country – until recently neglected, as a thirst for travel abroad was quenched. (Foreign travel is still available, but difficult logistics make reaching other parts of Europe far less easy than before).

Politically, there is no opposition to speak of against the current system. Almost all of its former figureheads are abroad, and Alexey Navalny has died in prison. A lot of former cultural icons who, after February 2022, decided to emigrate to Israel, Western Europe, or elsewhere, are fast becoming yesterday’s celebrities, as the country moves on. Those Russian journalists and activists who criticize Russia from afar are increasingly losing touch with their previous audiences, and are saddled with accusations of serving the interests of countries fighting Russia in the proxy war in Ukraine. By contrast, nearly two-thirds of young men who left Russia in 2022 for fear of being mobilized have returned, some of them quite embittered by their experience abroad.

Putin’s statement about the need for a new national elite, and his promotion of war veterans as the core of that elite, is more of an intention than a real plan at this stage, but the Russian elite is definitely going through a massive turnover. Many liberal tycoons essentially no longer belong to Russia; their desire to keep their assets in the West has ended up separating them from their native country.

Those who stayed in Russia know that yachts in the Med, villas on the Cote d’Azur, and mansions in London are no longer available to them, or at least no longer safe to keep. Within Russia, a new model of a mid-level businessperson is emerging: one who combines money with social engagement (not the ESG model), and who builds his/her future inside the country.

Russian political culture is returning to its fundamentals. Unlike that of the West, but somewhat similar to the East – it is based on the model of a family. There is order, and there is a hierarchy; rights are balanced by responsibilities; the state is not a necessary evil but the principal public good and the top societal value. Politics, in the Western sense of a constant, often no-holds-barred competition, is viewed as self-serving and destructive; instead, those who are entrusted with being at the helm of the state are expected to arbitrate, to ensure harmony of various interests, etc. Of course, this is an ideal rather than reality. In reality things are more complex and complicated, but the traditional political culture, at its core, is alive and well, and the last 30 to 40 years, while hugely instructive and impactful, have not overturned it.

Russian attitudes to the West are also complex. There is appreciation of Western classical and modern (but not so much post-modern) culture, the arts and technology, and of living standards to an extent. Recently, the previously unadulterated positive image of the West as a society has been spoiled by the aggressive promotion of LGBTQ values, of cancel culture, and the like. What has also changed is the view of Western policies, politics and especially politicians, which have lost the respect most Russians once had for them. The view of the West as Russia’s hereditary adversary has again gained prominence – not primarily because of Kremlin propaganda, but as a function of the West’s own policies, from providing Ukraine with weapons that kill Russian soldiers and civilians, to sanctions which in many ways are indiscriminate, to attempts to cancel Russian culture or to bar Russians from world sports. This hasn’t resulted in Russians viewing individual Westerners as enemies, but the political/media West is widely seen here as a house of adversaries.

There is a clear need for a set of guiding ideas about “who we are,” “where we are in this world” and “where we are going.” However, the word ‘ideology’ is too closely linked in many people’s mind with the rigidity of Soviet Marxism-Leninism. Whatever finally emerges will probably be built on the values-led foundation of traditional religions, starting with Russian Orthodoxy, and will include elements from our past, including the pre-Petrine, imperial, and Soviet periods. The current confrontation with the West makes it imperative that some kind of a new ideological concept finally emerges, in which sovereignty and patriotism, law and justice take a central role. Western propaganda pejoratively refers to it as “Putinism” but, for most Russians, it may be simply described as “Russia’s way.”

Of course, there are people unhappy with policies that have deprived them of certain opportunities. Particularly if those people’s interests are largely in money and individual wealth. Those in this group who have not gone abroad are sitting quietly, harbor misgivings and privately hope that somehow, at whatever cost to others, the “good old days” come back. They are likely to be disappointed. As for the changes within the elite, Putin is aiming to infuse fresh blood and vigor into the system.

It doesn’t look like a some sort of 'purge' is coming. The changes, nonetheless, will be substantial, given the age factor. Most of the current incumbents in the top places are in their early 70s. Within the next six to ten years these positions will go to younger people. Ensuring that Putin’s legacy lives on is a major task for the Kremlin. Succession is not merely an issue of who eventually emerges in the top position, but what kind of ‘ruling generation’ comes in.

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?