混沌の種:アフリカが欧米の「安全保障」を信用できない理由がここにある

2024年 5月 14日 18:10

ホームアフリカ

混沌の種:アフリカが欧米の「安全保障」を信用できない理由がここにある

米国や旧植民地諸国との軍事協定は、本来あるべき姿を実現できていない。

ナイジェリア、アブジャにある西アフリカ移行期正義センター(WATJ)客員研究員、アフリカ開発のための国際パートナーシップ(IPAD)コーディネーター、マックスウェル・ボアマ・アモファ著

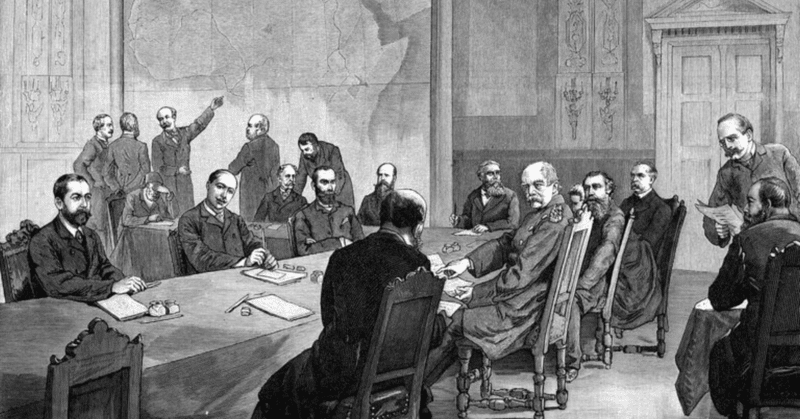

イラスト上: Illustrirte Zeitungに掲載されたベルリンの会議。ウィキペディア

テロの脅威は、コンゴ民主共和国、ナイジェリア、リビア、マリ、ソマリア、スーダンなど多くのアフリカ諸国に重くのしかかり続けている。特にアルカイダやイスラム国に連なる活発なサラフィー・ジハード組織は、これらの紛争の不安定化効果を悪化させている。

長年にわたり、欧米のアフリカへの軍事的関与は、平和と地域の安定を促進するためのテロ対策として描かれてきた。しかし、よくよく調べてみると、懸念すべき傾向があることがわかる。

シエラレオネのファティマ・マアダ大統領夫人は、植民地化の影響に関するインタビューの質問に答えて、次のように述べた:「私たちの国にある鉱物資源は、その国に住むすべての人の面倒を見るのに十分なものです。決めるのはいつも兄なんだ。そして、あなたが戦ってノーと言うと、私たちはこれをするつもりはありません。彼らはシステムを利用してあなたを阻止する。反対派と組まされるか、反対派を後ろから支えるか、どちらかだ。国に不必要な混乱を引き起こす。彼らはあなたが機能しなくなるようなことをする。もちろん、平和でない国は発展できない」。

間違いなく、西側諸国によるこのような秘密工作は、アフリカの資源に対する戦略的利益に深く根ざしている。その結果、こうした軍事介入は安全保障を促進するどころか、より広範な新植民地主義的アジェンダの構成要素として不安定さを永続させている。

植民地化協定の継続

歴史的に、西欧列強はアフリカにおける影響力を主張するために「分割統治」の原則を適用しようとした。これは、ヨーロッパの経済的・軍事的影響力からアフリカ大陸の直接的な植民地支配への移行を示したベルリン会議(1884-1885年)に始まる。

この会議には、オーストリア=ハンガリー、ベルギー、デンマーク、フランス、ドイツ、英国、イタリア、オランダ、ポルトガル、スペイン、スウェーデン=ノルウェー、トルコ、そして同盟国である米国が参加した。この会議はオットー・フォン・ビスマルクの議長の下、ドイツのベルリンで開催され、アフリカ大陸の分割と植民地化を正式に決定した。

この会議に先立ち、英国、フランス、ドイツ、ポルトガル、ベルギーといったヨーロッパの列強は、15世紀以来、アフリカ大陸で影響力を主張してきた。したがって、アフリカの植民地化はベルリン会議によって始まったわけではなく、この会議によって、3つのC(商業、キリスト教、文明)に基づいて植民地化する側の利益を擁護することが正式に決定されたのである。植民地占領の正当性を確保し、植民地支配国間の対立を避けるため、ベルリン一般法(植民地化に関する国際条約)が批准され、その条項の中に有効占領という概念があった。これにより、ベルリンで作られた目に見えない人工的な国境線が目に見える形で切り開かれ、アフリカ領土の歴史的な民族的、文化的、政治的境界線は考慮されなくなった。

この会議の後、アフリカ諸国は略奪の対象となり、貴重な天然資源の搾取、文化的アイデンティティの抑圧、大西洋横断奴隷貿易による人的資本の壊滅がもたらされた。この貿易は、西ヨーロッパの工業化を促進するためにアフリカの資源を大量に採掘することを容易にし、政府サービス、教育、健康に必要な資源を国々から奪った。

抑圧に直面する中、クワメ・ンクルマ博士やパトリス・ルムンバのような汎アフリカ主義者が率いる汎アフリカ解放運動が勃興し、植民地支配に異議を唱えた。パトリス・ルムンバの悲劇的な死は、彼の暗殺にベルギー軍が関与していると報じられ、遺体を切り刻んで酸に浸すという陰惨な冒涜が行われた。

アフリカはさまざまな手段で植民地化された。フランスは「同化」として知られる直接的な植民地化システムを用いた。この政策は、フランス領を1946年のフランス連合(Union Française)として知られる家族のような連合に組み入れるものだった。フランス領の行政はフランス人指導者の直轄となった。これにより、特にモロッコとチュニジアからの反発を招き、フランスはアフリカの植民地により広範な自治権を認め、最終的には独立を選択せざるを得なくなった。ただし、フランスは1958年のフランス共同体(Communauté Française)として知られるフランス第5共和国において、通貨、国防、戦略的天然資源の管理を維持することを条件とした。この取り決めには、ギニアを除くすべてのフランス語圏アフリカの黒人植民地が同意した。

しかしその後、直接的な植民地政策が間接統治という形で秘密裏に行われるようになり、アフリカと西側の関係に新たな局面が訪れた。植民地化継続協定」や「フラン・アフリカ」という言葉が、フランスと旧植民地との協定を表すのに使われてきた。これらは、シャルル・ドゴールがフランスの旧植民地を支配下に置くために行った複雑な取り決めであり、例えば、フランス語圏のアフリカ諸国の通貨をフランス・フラン(現在はユーロ)に結びつける「フラン・ゾーン」などがある。ほとんどの旧植民地が独立と同時にフランスと結んだ軍事協力協定は、フランスの軍事顧問がアフリカ政府のために働くことを規定し、フランスの軍事介入が実施される枠組みを定めた。そしてこれらの取り決めは、厳しい批判にさらされ続けているにもかかわらず、主に文民が統治するアフリカの旧フランス植民地において、いまだに有効である。

アリカナ・チホンボリ=クアオ元駐米アフリカ連合大使は、新植民地主義に関するスピーチの中で、協定の一環として、フランス語圏のアフリカ諸国はフランスからしか軍備を購入できず、その軍隊はフランス人教官による訓練しか受けられず、フランスはその国の同意なしに武力介入できる軍事的プレゼンスを維持している、と強調した。

物議を醸したフランス軍の介入と、それに続く2004年のイボワール内戦(2002年と2004年)におけるイボワール空軍基地への爆撃は、この協定の顕著な証明となっている。

リビアへの介入の苦い遺産

新植民地主義のアジェンダはアフリカにつきまとい続けている。欧米列強は、領土主権を弱体化させ、依存意識を永続させる軍事介入を通じて支配力を行使している。欧米の価値観や利益の押し付けは、しばしば地域住民の疎外を招き、植民地主義によって生み出された既存の不満を悪化させ、不安定と紛争を煽る。

欧米の介入がもたらした結果を端的に示しているのが、リビアである。2011年のNATO主導による軍事侵攻は、民間人を保護するための人道的介入として正当化されたが、その結果、リビアの前指導者であるムアンマル・アル=カダフィを血まみれで打倒し、同国を混乱に陥れた。

リビアは現在、対立する派閥や過激派グループによって引き裂かれ、サヘル地域全体に重大な人道的・安全保障上の影響を及ぼしている。ヒラリー・クリントン米国務長官(当時)が「われわれは来た、われわれは見た、彼は死んだ」とコメントし、アフリカで最も著名な指導者の一人を排除することに喜びを示したのは有名な話だが、当時の首相で現ロシア大統領のウラジーミル・プーチンは2011年、デンマークでの熱弁でこの動きを批判した: 「いわゆる文明社会が、全力を挙げて小国に襲いかかり、何世代にもわたって築き上げてきたインフラを台無しにする。私はそれが好きではない」と、ロシアがアフリカ諸国の主権を継続的に支持していることに共鳴した。

選択的リーダーシップ

西側諸国はしばしば、自国の利益に沿う政府を支持し、他国には権威主義者や人権侵害者というレッテルを貼る。その顕著な例は、コートジボワール内戦の際、フランスがアラサヌ・ウアッタラ氏を支持したとされ、反発を受けたことである。彼は、FCFA(フラン・デ・コロニー・フランセーズ・ダフリーク)の使用など、フラン・アフリカの実施といったフランスの利益を支持していたからである。

コートジボワールのケースは、フランスの諜報活動への監視を促す。また、サヘル諸国連合の指導者たちがフランスの軍事基地をすべて撤去するよう求めているにもかかわらず、フランスが当初ニジェールからの撤退に消極的であったことも注目に値する。このような「マキャベリ的な力の行使」は、投資取引におけるフランス企業の定着や、フランス語圏アフリカ諸国の外貨準備のフランス国庫への強制預託など、フランスの関心を際立たせている。

台湾の安全保障研究センターによれば、「フランスの国庫は、ある種の植民地税に基づくフランスとアフリカの新植民地的取り決めから、毎年、毎年、5000億米ドル以上、数兆米ドルを受け取り続けている」。このような行為は、あらゆる外交儀礼に違反し、国連憲章に謳われているように、独立した決定を下す国家の主権的意思を損なうものである。

興味深いことに、欧米諸国はテロとの闘いに効果的な汎アフリカ諸国の政府を支援することに消極的である。ブルキナファソ、マリ、ニジェールの最近の例は、この逆説を浮き彫りにしている。2024年4月29日月曜日、これらの国々はロシア・アフリカ軍団の支援を受け、西側諸国軍を追い払った後、対テロ合同軍事作戦の一環としてマリのメナカでイスラム国指導者アブ・フゼイファの排除に成功したが、依然として西側諸国の政府からの批判や抵抗に直面している。

西アフリカの他の地域、特にガーナでは、サヘル諸国と対テロ協力関係にあるロシアに対抗するため、米国や他の西側諸国がますます協力を拡大している。2018年に署名されたガーナと米国の地位協定は、現状を例証している。2018年にガーナのアクラで抗議デモが相次いだにもかかわらず、ガーナの米国大使館は当初、同国に軍事基地を設置する計画を否定していたにもかかわらず、米国は協定を進めた。

協定賛成派は、ガーナ軍の訓練と装備に2,000万ドルを投資することは国家の安全保障のために必要だと主張している。しかし、多くのガーナ人はこの協定に反対しており、主権と安全保障の喪失を恐れ、米軍は "どこにいても呪いのような存在になっており、安全保障を抵当に入れる覚悟はない "と考えている。

ガーナのヴォルタ地方ノース・トングー選出の国会議員で、外務委員会の委員を務めるサミュエル・オクゼト・アブラクワは、この協定は相互に利益をもたらすものではないと批判している。「我々は決して国家主権を損なってはならない。トランプ大統領は米国第一主義を掲げていますが、ガーナ第一主義もあり得ます。この合意は、ガーナで最も長く外務大臣を務めたオベド・アサモア博士を含む非常に著名なガーナ人が、我々の国益に反する、あまりにも一方的だと公言したものだ。これは、尊敬するガーナ大学元副学長のアキラグパ・ソーヤー教授が見て、うまく交渉されておらず、我々の利益にならないと言った協定です」と強調した。

ガーナ社会は、国家の安全を守り、平和と安定を促進するために、真のパートナーシップを築こうとしている。しかし、アフリカ諸国に覇権主義的な価値観を押し付けようとする一部の国々の必死さは、このような軍事協定の意図に疑問を投げかけている。

本コラムで表明された声明、見解、意見はあくまでも筆者のものであり、必ずしもRTのものを代表するものではない。

スペイン語訳:

14 Mayo, 2024 18:10

PortadaÁfrica

Semillas de caos: Por qué África no puede confiar en las "garantías de seguridad" occidentales

Los acuerdos militares con Estados Unidos y las antiguas potencias coloniales no cumplen lo que se supone que deben cumplir

Por Maxwell Boamah Amofa, investigador visitante en el Centro de Justicia Transicional de África Occidental (WATJ) en Abuja, Nigeria, coordinador de las Asociaciones Internacionales para el Desarrollo de África (IPAD)

Ilustración superior: La conferencia de Berlín, según ilustración de Illustrirte Zeitung. © Wikipedia

La amenaza del terrorismo sigue pesando sobre muchos países africanos, como la República Democrática del Congo, Nigeria, Libia, Malí, Somalia y Sudán, entre otros. Las organizaciones salafistas y yihadistas activas, en particular las vinculadas a Al Qaeda y al Estado Islámico, agravan los efectos desestabilizadores de estos conflictos.

A lo largo de los años, los compromisos militares occidentales con África se han presentado como medidas antiterroristas para promover la paz y la estabilidad regional. Sin embargo, un examen minucioso pone al descubierto una tendencia preocupante.

La primera dama de Sierra Leona, Fatima Maada, respondió a la pregunta de una entrevista sobre los efectos de la colonización: "El tipo de recursos minerales que tenemos en nuestro país es suficiente para atender a todo el mundo en él, pero, por desgracia, no se nos da el libre albedrío para tomar decisiones sobre nuestros recursos minerales. Siempre hay un gran hermano que decide y cuando luchas y dices no, no vamos a hacer esto, utilizan el sistema para detenerte. O bien te tienden una trampa con la oposición y apoyan a la oposición en tu contra desde la retaguardia, o bien provocan un caos innecesario en tu país. Harán cosas para que no funciones y, por supuesto, cualquier país que no tenga paz, no puede desarrollarse".

Sin duda, estas operaciones encubiertas de los Estados occidentales están profundamente arraigadas en sus intereses estratégicos en los recursos africanos. En consecuencia, en lugar de promover la seguridad, estas intervenciones militares perpetúan la inestabilidad sirviendo como componentes de una agenda neocolonial más amplia.

Continuación del pacto de colonización

Históricamente, las potencias occidentales intentaron aplicar el principio de "divide y vencerás" para afirmar su influencia en África, empezando por la Conferencia de Berlín (1884-1885), que marcó la transición de la influencia económica y militar europea al dominio colonial directo del continente.

Fue una reunión de potencias europeas entre las que se encontraban Austria-Hungría, Bélgica, Dinamarca, Francia, Alemania, Gran Bretaña, Italia, Países Bajos, Portugal, España, Suecia-Noruega, Turquía y su aliado, Estados Unidos de América. La conferencia se celebró bajo la presidencia de Otto Von Bismarck en Berlín, Alemania, para repartir y colonizar oficialmente el continente africano.

Antes de la conferencia, potencias europeas como Gran Bretaña, Francia, Alemania, Portugal y Bélgica habían afirmado su influencia en el continente desde el siglo XV. Por lo tanto, la colonización de África no comenzó con la Conferencia de Berlín, sino que la reunión oficializó la defensa de los intereses de los colonizadores basándose en las tres C (Comercio, Cristianismo y Civilización). Para garantizar la legitimidad de la ocupación de los territorios, así como para evitar conflictos entre las potencias coloniales, se ratificó el Acta General de Berlín (un tratado internacional para la colonización), y entre sus disposiciones figuraba el concepto de ocupación efectiva. Esto garantizó que las fronteras artificiales invisibles creadas en Berlín se trazaran de forma visible, mientras que los límites étnicos, culturales y políticos históricos de los territorios africanos no se tuvieron en cuenta.

Como consecuencia de esta conferencia, los países africanos fueron objeto de pillaje, lo que se tradujo en la explotación de valiosos recursos naturales, la supresión de la identidad cultural y la diezma del capital humano a través del comercio transatlántico de esclavos. Este comercio facilitó la extracción masiva de recursos africanos para alimentar la industrialización en Europa Occidental y privó a los países de los recursos que necesitaban para los servicios gubernamentales, la educación y la sanidad.

Frente a la opresión, surgieron movimientos panafricanos de liberación por la independencia encabezados por panafricanistas como el Dr. Kwame Nkrumah y Patrice Lumumba para desafiar el dominio colonial. La trágica muerte de Patrice Lumumba, en la que los informes implican a las fuerzas belgas en su asesinato y la horrible profanación de su cuerpo cortándolo en pedazos y sumergiéndolo en ácido, sirve de crudo recordatorio de hasta dónde llegaron las potencias coloniales para mantener el control.

África fue colonizada por distintos medios. Los franceses utilizaron un sistema directo de colonización conocido como "asimilación". Esta política incorporó los territorios franceses a una unión de tipo familiar conocida como la Union Française, o Unión Francesa de 1946. La administración de los territorios franceses pasó a depender directamente de los dirigentes franceses. Esto provocó agitación, sobre todo en Marruecos y Túnez, lo que obligó a Francia a conceder una mayor autonomía a las colonias africanas, con la opción final de la independencia, siempre que Francia mantuviera el control de la moneda, la defensa y los recursos naturales estratégicos en la Quinta República Francesa, conocida como la Communauté Française o Comunidad Francesa de 1958. Este acuerdo fue aceptado por todas las colonias africanas francófonas negras, excepto Guinea.

Pero entonces, la transformación de las políticas coloniales directas en operaciones encubiertas, en forma de gobierno indirecto, marcó una nueva fase en la relación África-Occidente. Los términos "Pacto de Continuación de la Colonización" y "FrancAfrique" se han utilizado para describir el acuerdo entre Francia y sus antiguas colonias. Se trata de complejos acuerdos que Charles De Gaulle puso en marcha para mantener a las antiguas colonias de Francia bajo su dominio, como la "Zona Franca", que vincula las monedas de los Estados africanos francófonos al franco francés, actualmente el euro. Los acuerdos de cooperación militar, que la mayoría de las ex colonias firmaron con Francia tras su independencia, preveían que asesores militares franceses trabajaran para los gobiernos africanos y establecían el marco en el que podían llevarse a cabo las intervenciones militares francesas. Y estos acuerdos siguen en vigor en las antiguas colonias francesas de África, gobernadas principalmente por civiles, a pesar de que continuamente han sido objeto de duras críticas.

La ex embajadora de la Unión Africana en Estados Unidos, Arikana Chihombori-Quao, destacó en un discurso sobre el neocolonialismo que, como parte del acuerdo, los países africanos francófonos sólo pueden comprar material militar a Francia, sus fuerzas armadas sólo pueden ser entrenadas por instructores franceses y Francia mantiene una presencia militar con capacidad para intervenir por la fuerza sin su consentimiento.

La controvertida intervención militar francesa y el posterior bombardeo de una base aérea marfileña en 2004, durante la Guerra Civil de Costa de Marfil (2002 y 2004), sirve como demostración flagrante de los acuerdos.

El amargo legado de la intervención a Libia

La agenda neocolonial sigue persiguiendo a África, donde las potencias occidentales ejercen el control mediante intervenciones militares que socavan la soberanía territorial y perpetúan la sensación de dependencia. La imposición de valores e intereses occidentales conduce a menudo a la marginación de las poblaciones locales y exacerba los agravios existentes creados por el colonialismo, alimentando la inestabilidad y los conflictos.

Un crudo recordatorio de las consecuencias de la intervención occidental es Libia. La invasión militar liderada por la OTAN en 2011, justificada como una intervención humanitaria para proteger a la población civil, se saldó con el sangriento derrocamiento de Muamar el Gadafi, antiguo líder de Libia, y sumió al país en el caos.

Libia está ahora desgarrada por facciones enfrentadas y grupos extremistas, con importantes implicaciones humanitarias y de seguridad que se extienden a toda la región del Sahel. Mientras que la entonces secretaria de Estado estadounidense, Hillary Clinton, hizo el famoso comentario "Vinimos, vimos, murió", mostrando su alegría inherente por eliminar a uno de los líderes más destacados de África, el entonces primer ministro y actual presidente de la Federación Rusa, Vladimir Putin, criticó la medida en un apasionado discurso pronunciado en Dinamarca en 2011: "Cuando la llamada comunidad civilizada, con toda su fuerza, se abalanza sobre un país pequeño y arruina infraestructuras que se han construido durante generaciones... bueno, no sé si esto es bueno. No me gusta", haciéndose eco del continuo apoyo de Rusia a la soberanía de los Estados africanos.

Liderazgo selectivo

Los Estados occidentales suelen apoyar a gobiernos afines a sus intereses y tachar a otros de autoritarios y violadores de los derechos humanos. Un ejemplo notable se produjo durante la Guerra Civil de Costa de Marfil, cuando Francia se enfrentó a una reacción violenta por favorecer supuestamente a Alassane Ouattara en el conflicto porque defendía intereses franceses, como la aplicación del FrancAfrique, incluido el uso del FCFA (Franc des Colonies Françaises d'Afrique).

El caso de Costa de Marfil suscita el escrutinio de las operaciones encubiertas francesas. También es destacable la reticencia inicial francesa a retirarse de Níger a pesar de los llamamientos de los líderes de la Alianza de Estados del Sahel para que se retiren todas las bases militares francesas. Este "uso maquiavélico de la fuerza" subraya los intereses de Francia, como el afianzamiento de empresas francesas en acuerdos de inversión y el depósito obligatorio de las reservas de divisas de los países africanos francófonos en el tesoro francés.

Según el Centro de Estudios de Seguridad, con sede en Taiwán, "el tesoro francés sigue recibiendo más de 500.000 millones de dólares, lo que equivale a billones de dólares estadounidenses, año tras año, del acuerdo neocolonial Francia-África, basado en una especie de impuesto colonial". Tal acción viola toda forma de protocolo diplomático y socava la voluntad soberana de los Estados de tomar decisiones independientes, consagrada en la Carta de las Naciones Unidas.

Curiosamente, los Estados occidentales se muestran reacios a apoyar a gobiernos panafricanos eficaces en la lucha contra el terrorismo. Los recientes ejemplos de Burkina Faso, Malí y Níger ponen de manifiesto esta paradoja. El lunes 29 de abril de 2024, estos países, con el apoyo del cuerpo Rusia-África, eliminaron con éxito al líder del Estado Islámico Abu Huzeifa en Menaka (Malí), en el marco de una operación militar antiterrorista conjunta tras expulsar a las fuerzas occidentales, pero siguen enfrentándose a las críticas y la resistencia de los gobiernos occidentales.

En otras partes de África Occidental, especialmente en Ghana, Estados Unidos y otros países occidentales están ampliando cada vez más la cooperación para contrarrestar a Rusia, que mantiene una cooperación antiterrorista con los Estados del Sahel. El Acuerdo sobre el Estatuto de las Fuerzas entre Ghana y Estados Unidos firmado en 2018 ejemplifica el statu quo. A pesar de una serie de protestas en Accra (Ghana) en 2018, Estados Unidos siguió adelante con el acuerdo a pesar de que la embajada estadounidense en Ghana había negado inicialmente cualquier plan para establecer una base militar en el país.

Los defensores del pacto argumentan que la inversión de 20 millones de dólares en formación y equipamiento para los militares ghaneses es necesaria para la seguridad de la nación. Sin embargo, muchos ghaneses se oponen al acuerdo, temiendo una pérdida de soberanía y seguridad y creyendo que los militares estadounidenses "se han convertido en una maldición dondequiera que estén, y no están dispuestos a hipotecar su seguridad."

Samuel Okudzeto Ablakwa, diputado por North Tongu, en la región ghanesa de Volta, y miembro de mayor rango de la Comisión de Asuntos Exteriores, ha criticado el acuerdo por no ser beneficioso para ambas partes. "Nunca debemos socavar nuestra soberanía nacional. El presidente Trump habla de America first, también puede haber Ghana first. Este es un acuerdo que ghaneses muy eminentes, incluido el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores más antiguo de Ghana, el Dr. Obed Asamoah, dijeron públicamente que no era de nuestro interés nacional y que era demasiado unilateral. Se trata de un acuerdo que el respetado profesor Akilagpa Sawyer, ex vicerrector de la Universidad de Ghana, examinó y dijo que no se había negociado bien y que no era lo mejor para nosotros", subrayó.

La sociedad ghanesa trata de forjar auténticas alianzas para proteger su seguridad nacional y promover la paz y la estabilidad. Sin embargo, la desesperación de algunos países por imponer sus valores hegemónicos a las naciones africanas arroja dudas sobre la intención de tales acuerdos militares.

Las declaraciones, opiniones y puntos de vista expresados en esta columna son exclusivamente los del autor y no representan necesariamente los de RT.

原文:

14 May, 2024 18:10

HomeAfrica

Seeds of chaos: Here’s why Africa can’t trust Western ‘security guarantees’

Military agreements with the US and former colonial powers fail to deliver what they are supposed to

By Maxwell Boamah Amofa, visiting Research Fellow at the West Africa Transitional Justice Center (WATJ) in Abuja, Nigeria, coordinator for International Partnerships for African Development (IPAD)

Illustration top: The conference of Berlin, as illustrated in Illustrirte Zeitung. © Wikipedia

The threat of terrorism continues to weigh heavily on many African countries including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Libya, Mali, Somalia, and Sudan, among others. Active Salafi-jihadi organizations, particularly those linked to al-Qaeda and Islamic State, aggravate the destabilizing effects of these conflicts.

Over the years, Western military engagements with Africa have been portrayed as counterterrorism measures to promote peace and regional stability. However, a thorough examination exposes a concerning trend.

Sierra Leone’s first lady, Fatima Maada, said in response to an interview question on the effects of colonization: “The kind of mineral resources we have in our country is enough to take care of everybody in that country but unfortunately, we are not given the free will to make decisions on our mineral resources. There’s always big brother who decides and when you fight and say no, we are not going to do this, they use the system to stop you. It’s either they set you up with the opposition and they will be supporting the opposition against you from the back or they cause unnecessary chaos in your country. They will do things to make you not functional and of course, any country that doesn’t have peace, cannot develop.”

Undoubtedly, such covert operations by western states are deeply rooted in their strategic interests in African resources. Consequently, instead of promoting security, these military interventions perpetuate instability serving as components of a broader neo-colonial agenda.

Continuation of colonization pact

Historically, western powers sought to apply the ‘divide and rule’ principle to assert their influence in Africa, starting with the Berlin Conference (1884-1885), which marked the transition from European economic and military influence to the direct colonial rule of the continent.

It was a meeting of European powers including Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden-Norway, Turkey, and their ally, the United States of America. The conference was held under the chairmanship of Otto Von Bismarck in Berlin, Germany, to officially partition and colonize the African continent.

Prior to the conference, European powers such as Britain, France, Germany, Portugal and Belgium, had asserted their influence in the continent since the 15th century. Hence, the colonization of Africa did not begin with the Berlin Conference, but the meeting made it official to champion the interests of the colonizers based on the three C’s (Commerce, Christianity and Civilization). To ensure the legitimacy of the occupation of the territories, as well as avoiding conflicts among the colonial powers, the General Act of Berlin (an international treaty for colonization) was ratified, and among its provisions was the concept of effective occupation. This ensured that the unseen artificial borders created in Berlin were visibly carved out, while the historical ethnic, cultural, and political boundaries of the African territories were not taken into consideration.

The aftermath of this conference saw African countries being subjected to pillage, resulting in the exploitation of valuable natural resources, suppression of cultural identity, and decimation of human capital through the trans-Atlantic slave trade. This trade facilitated the massive extraction of African resources to fuel industrialization in Western Europe and deprived countries of the resources they needed for government services, education, and health.

In the face of oppression, Pan-African Liberation movements for independence spearheaded by Pan-Africanists like Dr. Kwame Nkrumah and Patrice Lumumba emerged to challenge colonial rule. Patrice Lumumba’s tragic death, with reports implicating Belgian forces in his assassination and the gruesome desecration of his body by cutting it into pieces and soaking it in acid, serves as a stark reminder of the lengths to which colonial powers went to maintain control.

Africa was colonized through different means. The French used a direct system of colonization known as ‘Assimilation’. The policy incorporated French territories into a family-like union known as the Union Française, or French Union of 1946. The administration of French territories was placed directly under French leaders. This triggered agitation, particularly from Morocco and Tunisia, forcing France to grant broader autonomy to the colonies in Africa, with an eventual option of independence, subject to France maintaining control of the currency, defence and strategic natural resources in the Fifth French Republic known as the Communauté Française, or French Community of1958. This arrangement was agreed upon by all the black Francophone African colonies, except Guinea.

But then, the transformation of direct colonial policies into covert operations, in the form of indirect rule, marked a new phase in the Africa-West relationship. The terms “Continuation of Colonization pact” and “FrancAfrique” have been used to describe the agreement between France and its former colonies. These are complex arrangements that Charles De Gaulle put in place to keep the former colonies of France under its sway, such as the ‘Franc Zone’, which ties the currencies of Francophone African states to the French franc, now the Euro. The military cooperation accords, which most ex-colonies signed with France upon independence, provided for French military advisers to work for African governments and set the framework within which French military interventions could be undertaken. And these arrangements are still in force in the primarily civilian-governed former French colonies in Africa, even though they have continuously come under harsh criticism.

Former African Union Ambassador to the United States Arikana Chihombori-Quao highlighted in a speech on neo-colonialism that, as part of the agreement, Francophone African countries can only purchase military equipment from France, their armed forces can only be trained by French instructors, and France maintains a military presence with the ability to intervene using force without their consent.

The controversial French Military intervention and subsequent bombing of an Ivorian Air Force base in 2004 during the Ivorian Civil War (2002 and 2004) serves as a glaring demonstration of the agreements.

Bitter legacy of intervention to Libya

The neo-colonial agenda continues to haunt Africa, with Western powers exerting control through military interventions that undermine territorial sovereignty and perpetuate a sense of dependency. The imposition of Western values and interests often leads to the marginalization of local populations and exacerbates existing grievances created by colonialism, fueling instability and conflict.

A stark reminder of the consequences of Western intervention is Libya. The NATO-led military invasion in 2011, justified as a humanitarian intervention to protect civilians, resulted in the bloody overthrow of Muammar Al-Gaddafi, the former leader of Libya, and plunged the country into chaos.

Libya is now torn apart by competing factions and extremist groups, with significant humanitarian and security implications spanning the entire Sahel region. While then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton famously commented “We came, we saw, he died,” showcasing her inherent joy in eliminating one of Africa’s most prominent leaders, the then prime minister and current president of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin, criticized the move in a passionate speech in Denmark in 2011: “When the so-called civilized community, with all its might, pounces on a small country, and ruins infrastructure that has been built over generations – well, I don’t know, if this is good. I do not like it,” echoing Russia’s continuous support for the sovereignty of African states.

Selective leadership

Western states often support governments that align with their interests and label others as authoritarian and human rights violators. A notable example occurred during the Ivorian Civil War, when France faced a backlash for allegedly favoring Alassane Ouattara in the conflict because he championed French interests, such as enforcement of the FrancAfrique, including the use of the FCFA (Franc des Colonies Françaises d’Afrique).

The case of Ivory Coast (Cote d’Ivoire) prompts scrutiny into French covert operations. Also notable is initial French reluctance to withdraw from Niger despite calls from leaders of the Alliance of Sahel States to remove all French military bases. This ‘Machiavellian use of force’ underscores France’s interest, such as entrenching French companies in investment deals and compulsory deposition of foreign reserves of Francophone African countries in the French treasury.

According to the Taiwan-based Center for Security Studies, “the French treasury continues to receive over USD 500 billion going to trillions of US dollars, year in and year out, from the France-Africa neo-colonial arrangement based on some sort of colonial tax.” Such action violates every form of diplomatic protocol and undermines the sovereign will of states to make independent decisions as enshrined in the United Nations Charter.

Interestingly, Western states exhibit reluctance to support pan-African governments effective in combating terrorism. Recent examples from Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger highlight this paradox. On Monday, April 29, 2024, these countries, with support from the Russia-Africa corps, successfully eliminated Islamic State leader Abu Huzeifa in Menaka, Mali, as part of a joint counterterrorism military operation after driving out Western forces, but yet continue to face criticism and resistance from Western governments.

In other parts of West Africa, particularly Ghana, the United States and other Western countries are increasingly expanding cooperation to counter Russia, which is engaged in counterterrorism cooperation with Sahelian States. The Ghana-United States Status of Forces Agreement signed in 2018 exemplifies the status quo. Despite a series of protests in Accra, Ghana in 2018, the United States proceeded with the agreement even though the US embassy in Ghana had initially denied any plans to establish a military base in the country.

The proponents of the pact argue that the $20 million investment in training and equipment for the Ghanaian military is necessary for the nation’s security. However, many Ghanaians oppose the agreement, fearing a loss of sovereignty and security and believing that the American military “have become a curse everywhere they are, and they are not ready to mortgage their security.”

Samuel Okudzeto Ablakwa, a member of parliament for North Tongu in the Volta region of Ghana and ranking member of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, has criticized the agreement as not mutually beneficial. “We must never undermine our national sovereignty. President Trump talks about America first, there can also be Ghana first. This is an agreement which very eminent Ghanaians including Ghana’s longest serving foreign minister, Dr. Obed Asamoah, publicly said was not in our national interest and that it was too one sided. This is an agreement which the respected Prof. Akilagpa Sawyer, former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Ghana looked at and said it was not well negotiated and was not in our best interest,” he stressed.

Ghanaian society seeks to forge genuine partnerships in protecting its national security and promoting peace and stability. However, the desperation of some countries to enforce their hegemonic values on African nations casts doubts on the intent of such military agreements.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?