インドがBRICSに欧米が築いた世界秩序の解体を望まない理由

2023年 8月 21日 14:28

ホームインド

インドがBRICSに欧米が築いた世界秩序の解体を望まない理由

台頭する大国グループがグローバル・ガバナンスを簒奪しようとすれば、自重で崩壊するだろう。

M.K. バドラクマール

ロシア、韓国、スリランカ、西ドイツ、パキスタン、アフガニスタン、ウズベキスタンで勤務し、最終的に駐トルコインド大使を退任したインドの元外交官。

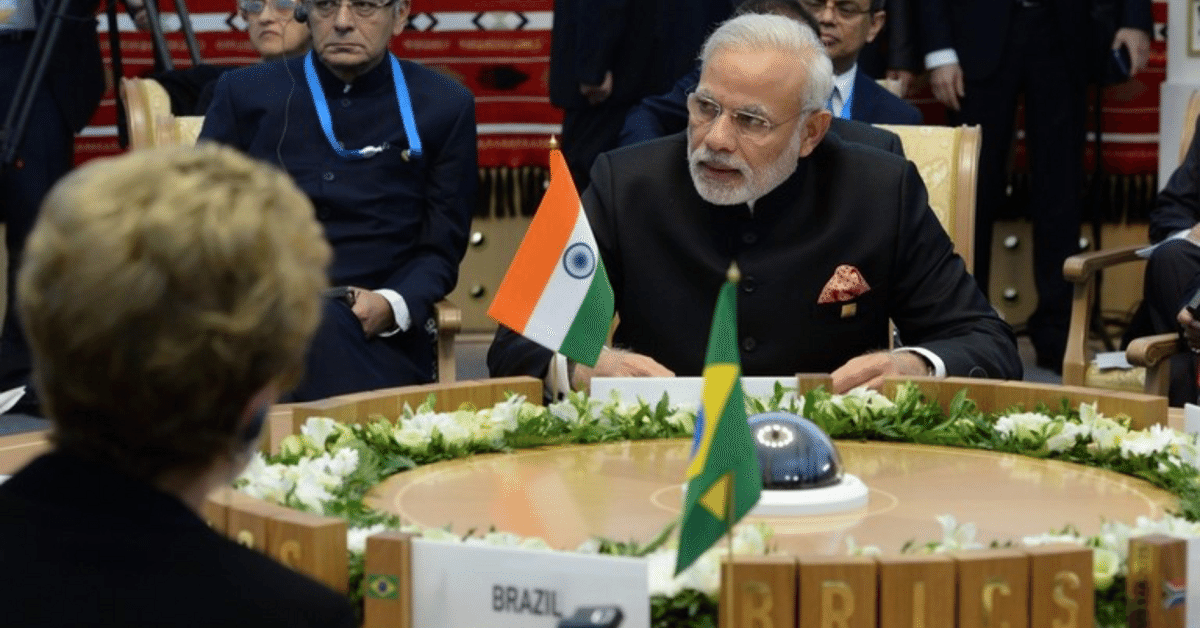

写真上:2015年7月9日、ロシアのウファで開催されたBRICS/SCO首脳会議に出席したナレンドラ・モディ・インド共和国首相 © Iliya Pitalev / Host Photo Agency/Ria Novosti via Getty Images

ボブ・ウッドワードが著書『Obama's Wars』で語った有名な事件が思い浮かぶ:2009年のクリスマスの1週間前、コペンハーゲンの金曜日の午後遅く、中国、インド、ブラジルの首脳が集まる非公開の会議に、バラク・オバマ大統領が中国政府関係者の抗議を無視して乱入した。

オバマは、「グローバル・サウス(南半球)」の最も強力な国々の3人の指導者、そして南アフリカのジェイコブ・ズマ大統領に、集団ではなく個別に会ってもらおうと考えていた。結局、オバマは4人の首脳と合流し、交渉は有意義な合意に達した。

この事件は、同年6月にエカテリンブルクで開催された第1回BRICs首脳会議からわずか6ヵ月後のことであったが、欧米の衰退が始まったという兆候はすでに出ていたものの、米国と欧州が世界経済と国際政治の特徴を長期にわたって決定し続けることに誰も疑いを持たなかったという、重大な真実を浮き彫りにした。

ロイター通信が「ナレンドラ・モディ首相はヨハネスブルグに行かないかもしれない」といういたずらな噂を流すなど、BRICS首脳会議に対するインドのアプローチが物議を醸している今日、見過ごされているのは、BRICSは世界秩序の破壊を目指すのではなく、この秩序に自分たちの利益を取り込むことを目指す修正主義的大国の共同体であるという、インドのグループに対する考え方に驚くべき一貫性があるということである。

しかし、時間は止まってはいなかった。グローバリゼーションは崩壊し、その基盤となっていた国際制度ももはや包括的なものではなくなっている。実際、ロシアと中国は米国の制裁下にある。それどころか、インドと米国との関係はおそらく歴史上最高の水準にあり、ほとんど準同盟のようなもので、ワシントンはそれを今世紀の「決定的なパートナーシップ」と表現している。米国の対中制裁は、インドにとって有利に働く可能性さえある。チップ産業における両国の緊密な結びつきは、その一例である。インドのエリートたちは、既存の国際秩序の破壊はおろか、最も根本的な再構築のために、ささやかな修正主義的願望を交換する理由もないだろう。

要するに、グローバル・アジェンダの主要な側面の形成においてBRICSの影響力が世界をより公正で安定したものにすることができれば、インドは満足だということだ。実際、BRICSは歴史の正しい側にいるのだから、それは突飛な夢ではない。数世紀にわたって蓄積された富を中心に、地域的・世界的な支配を確立する目的で行われた血なまぐさい戦争の歴史の中で、経済的な機会や政治的影響力を得てきたメンバーはいない。インドは我が家のようにくつろいでいる。

インドネシアからイラン、エジプト、サウジアラビアに至るまで、BRICSは、まるで欧米からグローバル・ガバナンスの旗印を引き継ぐような構えでいる。このような期待は、国際秩序全体があらかじめ決められた方向に進化することを前提としているため、非合理的である。

したがって、ブラジルが、あるいはインドが、今後BRICSのグローバル・ガバナンスへの貢献が真に決定的なものとなるにはどうすればよいのか、悩むのは当然のことである。根本的には、現在の状況でBRICSが過去の修正主義的な行動を維持することが可能かどうかさえ不透明なのである。問題は、ロシアが負けるはずのないウクライナ紛争の結果ではなく、破滅的な敗北を喫した後でも、敵対国が世界観を変える可能性は極めて低いということである。

したがって、BRICSが規範を欠いたまま拡大すれば、グループとしての一体性が損なわれ、拡散して効果がなくなる可能性がある。非同盟運動がそうだった。 しかし、この変革期は、政治の永遠の原則を苦悶の表情で語ったイェイツの言葉を借りれば、「最良の者は信念に欠け、最悪の者は情熱的な激しさに満ちている」時期でもある。

ウクライナ紛争と、BRICSの創設メンバーである中国とロシアに対するバイデン政権の二重の封じ込め戦略を背景に、この苦境は深刻だ。当然のことながら、中国とロシアの世界観は直近で劇的に変化し、米国の覇権主義に激しく対抗している。隣国の巨人同士の "際限のない "友情は、BRICSの中で両者をやや隔てており、そのことがグループの錬金術に影響を与えざるを得ない。

不思議なことに、BRICSとの提携を求める志願者の多くは、主にそのような理由でBRICSに惹かれている可能性さえある。世界の中小国家との関係において、より公正で利己的でないグローバル・ガバナンスを支持する第2の柱のようなものである。

強力な制度とグローバル・ガバナンスの経験はすべて、共通の価値観と利害の共有に基づく西側諸国の経験であることに間違いはない。皮肉なことに、それが彼らの "ブロック・メンタリティ "の原因でもある。BRICSにはそのような結束力がなく、G7が数十年にわたって行ってきたような世界のアジェンダを設定する能力もない。だからこそインドのような国は、BRICSという共同体が既存の世界秩序を破壊するのではなく、より良い方向に変えていくことを常に期待しているのだ。インドはグローバリゼーションや制度、国際法の崩壊を望んでいない。別の言い方をすれば、インドは既存の秩序の中で、その長所を維持し、短所を解消するようなルールや規範、協力の方法を作り出すことを好むのである。

インドにとって、これは戦術と戦略の問題である。現行のルールに基づく秩序はインドに安心感を与え、アジアの多極化を強化する。インドが米国との協調を迫られているというのは誤解である。以前はそうだったかもしれないが、現在のインドは、特に現指導部のもとで、自国の国益にかなうと考える米国との関係を意識的に拡大している。これは1990年代以降のインド政治の軌跡の論理的帰結であり、与党と主要野党の「超党派のコンセンサス」を享受している。そして、それはすでに不可逆的と思われる長期的な傾向となっている。

ここにはいくつかの要因が絡んでいるが、その主要な要因のひとつは、逆説的ではあるが、インドのBRICSパートナーである中国の驚異的な台頭であり、これがインド国内に警戒心を高めている。米国とのパートナーシップは、インドが安全保障のパラダイムに対処することを望む数少ない方法のひとつである。とはいえ、インドのBRICSパートナーは、インドが自国の国益に基づく独立した外交政策を追求し続けることを信頼できるし、信頼すべきである。世界をより公正で安定したものにするグローバル・アジェンダの主要な側面の形成において、インドがBRICSの決定的な影響力を信頼していることを疑う理由はない。

本コラムで表明された声明、見解、意見は、あくまでも筆者のものであり、必ずしもRTを代表するものではない。

原文:

21 Aug, 2023 14:28

HomeIndia

Why India doesn’t want BRICS to dismantle the world order built by the West

If the group of rising powers tries to usurp global governance, it will collapse under its own weight

M. K. Bhadrakumar

By M. K. Bhadrakumar, a retired Indian diplomat who has served in Russia, South Korea, Sri Lanka, West Germany, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Uzbekistan, before ultimately retiring as Indian Ambassador to Türkiye.

Photo top: Prime Minister of the Republic of India Narendra Modi at the BRICS/SCO Summits on July 09, 2015 in Ufa, Russia © Iliya Pitalev / Host Photo Agency/Ria Novosti via Getty Images

A famous incident narrated by Bob Woodward in his book Obama’s Wars comes to mind: President Barack Obama, disregarding the protestations of Chinese protocol officials, burst into a closed-door meeting of Chinese, Indian and Brazilian leaders on a late Friday afternoon in Copenhagen, a week before Christmas in 2009, where the three BRIC leaders (this was before South Africa joined and the group became BRICS) were negotiating in secret a common position at the climate talks, which were on the verge of complete meltdown.

Obama had wanted the three leaders of the most powerful nations of the “Global South” – and South African President Jacob Zuma – to meet him individually rather than collectively, and was frantic that his ploy was upended. Eventually, Obama joined the four leaders and the negotiations resulted in a meaningful agreement.

That incident, just six months after the first BRIC Summit in Yekaterinburg in June of that year, underscored a cardinal truth that although the signs were there already that the West’s decline had begun, no one had any doubts that the United States and Europe would continue to determine the characteristics of the world economy and international politics for a long time.

Today, when India’s approach to the upcoming BRICS Summit has become a matter of some controversy – with Reuters even floating a mischievous rumor that Prime Minister Narendra Modi might not travel to Johannesburg – what is being overlooked is that there is a remarkable consistency in India’s conception of the grouping: that BRICS was a community of revisionist powers who were not seeking the destruction of the world order, but the inclusion of their interests in this order.

However, time didn’t stand still. Globalization is moribund and the system of international institutions that provided its underpinnings are no longer inclusive. In fact, Russia and China are under US sanctions. On the contrary, India’s relationship with the US is perhaps at its highest point in history – almost a quasi-alliance – and Washington describes it as the “defining partnership” of the century. Arguably, the US sanctions against China could even hold advantages for India. The close bonding between the two countries that is in the pipeline for the chip industry is a case in point. Suffice to say, life may even be getting better for India, and the country’s elite would see no reason to trade its modest revisionist wishes for a most fundamental restructuring of the existing international order, let alone its destruction.

The bottom line is that India is content if the influence of BRICS in the shaping of the main aspects of the global agenda can make the world more just and stable. Indeed, that is not a far-fetched dream, as BRICS is on the right side of history. None of the group’s members have their economic opportunities and political influence grounded in a history of bloody wars, conducted with the purpose of establishing regional and global dominance centered around the wealth accumulated over several centuries. India feels at home.

This brings us to the core issue of the attraction that BRICS holds for so many countries today that are so patently divergent in their national characteristics, values, and interests – from Indonesia to Iran, Egypt to Saudi Arabia – who tend to regard the grouping as if it is poised to pick up the banner of global governance from the West. Such expectations are irrational, as they are premised on the evolution of the entire international order in a certain predetermined direction, which is of course not the case.

Thus, it is only natural that Brazil – or India, for that matter – may feel troubled as to how, moving forward, BRICS’ contribution to global governance can truly be decisive. Fundamentally, there is uncertainty as to whether, in the current circumstances, it is even possible for BRICS to maintain the revisionist behavior of the past. The issue is not about the outcome of the Ukraine conflict, which Russia cannot and will not lose, but that even after a catastrophic defeat, its adversaries are highly unlikely to change their views on the world.

Therefore, if BRICS expands, devoid of norms, the unity of the grouping could get impaired, rendering it diffuse and ineffectual. That was what happened to the Non-Aligned Movement. Yet, this is also a transformative period where “The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity,” to borrow Yeats’ anguished formulation of an eternal principle of politics.

The predicament is acute against the backdrop of the Ukraine conflict and the Biden administration’s dual containment strategy against China and Russia, two founding members of BRICS. Unsurprisingly, Chinese and Russian world views have dramatically changed in the most recent past and are robustly countering US hegemony. The “no limits” friendship between these neighboring giants sets them apart somewhat within BRICS, and that cannot but affect the alchemy of the grouping – although the collegial spirit continues, thanks to their pragmatism and sagacity.

Curiously, many of the aspirants who seek association with BRICS could even be getting attracted to the grouping principally for that reason – a sort of second pillar that upholds a more just and less selfish global governance in relation to the small and medium-sized states of the world.

Make no mistake that all the experience of strong institutions and global governance happens to be the experience of the West on the basis of common values and shared interests. Ironically, it also accounts for their “bloc mentality.” BRICS, on the contrary, lacks such cohesiveness and the capacity to set the world agenda, which the G7 had been doing for decades. That is why a country like India will always expect BRICS as a community to aim not at destroying the existing world order, but at changing it for the better. India does not want the collapse of globalization, institutions and international law. Put differently, India prefers to create within the existing order such rules, norms and ways of cooperation that would allow for the preservation of its advantages and the elimination of its shortcomings.

For India, this is both a matter of tactic and strategy. The prevailing rules-based order gives India a sense of security and strengthens multipolarity in Asia. It is a misconception that India is under pressure to bandwagon with the US. That might have been the case previously, but present-day India, under the current leadership in particular, is consciously expanding the relations with the US, which it considers to be in its own national interests. It is a logical outcome of the trajectory of politics in India since the 1990s and it enjoys a “bipartisan consensus” between the ruling party and the main opposition party. And it has become a long-term trend that already seems irreversible.

Several factors are involved here and one main factor is, paradoxically, the phenomenal rise of China, India’s BRICS partner, which raises alarmist sentiments in the country. The partnership with the US is one of the few ways India hopes to address the security paradigm. That said, India’s BRICS partners can and should trust India to continue to pursue an independent foreign policy based on its national interests. There is no reason to doubt that India reposes faith in the decisive influence of the BRICS in the shaping of the main aspects of the global agenda that will make the world more just and stable.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.