Blacksmithing: Work,Mythology and Gender

I originally wrote this contents for my BA(Hons) dissertation at University of Brighton in 2009.

Synopsis

This research project explore the role of blacksmiths, their skills, and their relation to mythology, and issues of gender. There are many mythologies related to blacksmithing all over the world and many myths are similar to each other. Blacksmiths were once seen to working very important profession in communities and therefore they were held in awe by people and even seen gods or demons.

As time passed by, only a few traditional blacksmiths survive today but at the same time artist blacksmiths are taking over traditions and using traditional skills. In history as in the present, blacksmithing has been regarded as male-dominated profession. However, there are now several remarkable women blacksmiths working in the same was as men. They have broken the barrier of gender of this profession, as this study will show.

Acknowledgements

I take this opportunity with great pleasure to thank especially Terry Tyhurst, the blacksmith working at Glynde Forge, for furthering my interests in the ways of a blacksmith life's work and history.

And I also wish to thank those who took a time for interviews: Naoto Uda (Japanese artist blacksmith), and Lucy Sandys-Clarke (English female blacksmith). It was a such a great opportunity to hear their experience of being blacksmiths in different countries and cultures.

Finally, I would like to thank my family who support me have and given me the chance to study in the UK.

Introduction

Working at Glynde Forge

I worked as assistant blacksmith for a traditional village blacksmith, Terry Tyhurst, in Glynde near Lewes for the whole summer of 2008.

When I was in my high scholl in Japan, I studied metalworking and specialized in especially was casting and never learnt forging until the 2nd year of my current course at the University of Brighton. Forging is very different from casting because of its directness when working on metal and I wanted to learn more about forging. That was the reason for wanting the work experience at the blacksmith.

The first time we talked on the phone, Terry was a bit surprised because he had been thought I would be a male from my earlier e-mail. I suppose he could not judge if I was woman or man from my name 'Ai'. When he said that, I thought he would not want a female helper but he answered, "That's alright then, if you can come over, we can talk about what cam I do for you." And that is how I got job at Glynde Forge.

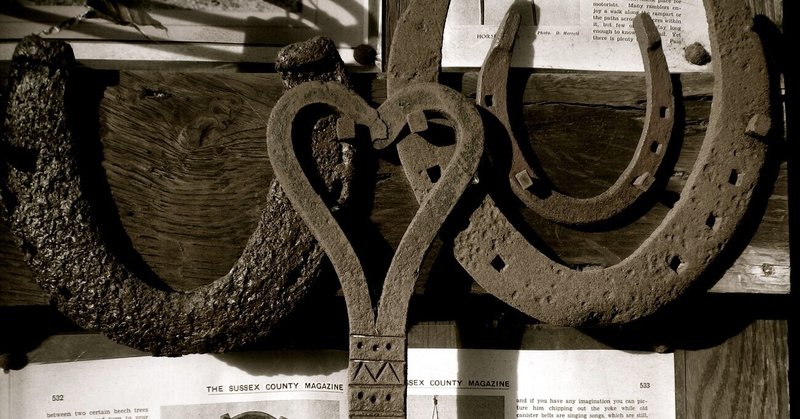

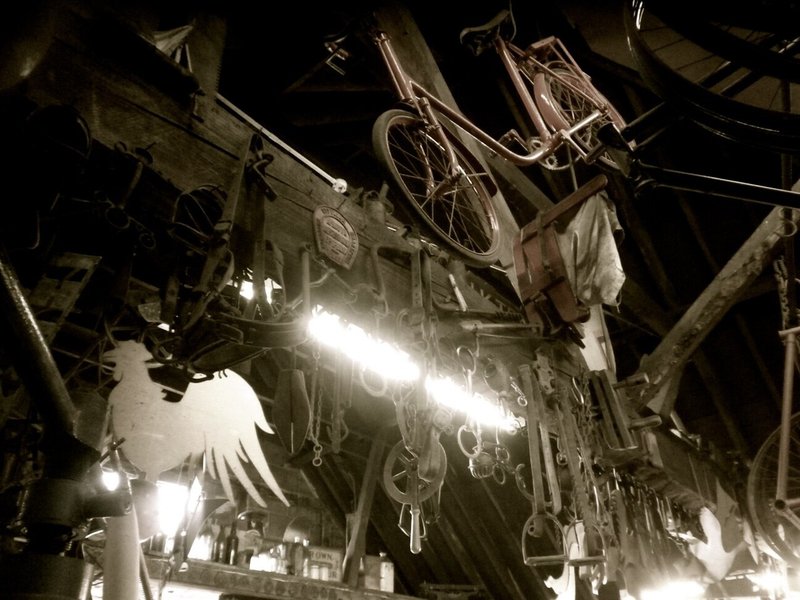

The Glynde Forge was built in 1907 with a huge wooden horseshoe gate at the entrance and the building inside and out is full of old tools, enamel signs and bicycles hanging everywhere. Terry Tyhurst calls them his collections, a man of great physical strength, with a moustache and very thick, wide hands. Although he uses an arc welding and power tools, all of his products are based on hand forged working methods. I had many interesting tea break conversations with him. He talked about old tools, gave me useful tips, discussed the previous blacksmiths who had worked at Glynde Forge, and about himself, and asked about what I am studying here, what I have been doing in Japan and Japanese blacksmithing.

These conversations with Terry, set off my interest in the difference of the blacksmithing trade in England, Europe and Japan. He also showed me many photographs of his work and many books about ironwork, and introduced me to his female blacksmith friend who works in Firle. She is also traditional village blacksmith and has her own forge. Many visitors came to the forge almost everyday, asking for jobs to be undertaken or just watching blacksmithing work. All of them looked at me with curiosity. "Why is young foreign woman is working here?" and some people actually asked me "Are you blacksmith as well?" and said, "It may be rude to say that but it is an unusual to see a young woman working at forge."

I found this new very interesting and this experience made me aware that a woman blacksmith is still very unusual even today. And so the theme of this research is to examine the blacksmith's role today and the place of woman in it in the setting of blacksmithing history, mythology. Finally this research will research how women blacksmiths overcame the barrier of gender to gain a career in this male-dominated profession. To complete this research project, I have many books about blacksmithing history and mythology over the world by authors including Mircea Eliade, and Kunio Yanagida, a Japanese scholar known as "the father of Japanese native ethnology".

Appearance and inside of Glynde Forge / Terry Tyhurst , Photo by Ai Iijima

Chapter 1

Cultural background

Blacksmithing is the one of the oldest profession in man's history and blacksmiths have transmitted their skills to work in iron worldwide from generation to generation. It is believed that Hittites (Ancient people in Asia Minor who flourished from 1600 to 1200 B.C.) were pioneers of the Iron Age in a discovery of iron metallurgy. W.F.Jackson Knight has remarked that Ancient people had already produced ironware by using meteorite fragments before learning smelting. Iron was thought 'as precious as gold'.

By finding the processes for smelting iron, people were then able to produce as much ironware as they needed. Mircea Eliade wrote: 'unlike copper and bronze, the metallurgy of iron very soon became industrialized'. Ironware especially when used in weapons, was much stronger than ones made of stone and bronze and as cultures developed iron manufacturing industries became vital to improving national power. Therefore, the technique of iron manufacturing was treated as military secret and only certain artisans knew about that peculiar technique. This secret works of iron went the round after Hittite had fallen.

Although many nations acquired the knowledge of producing the ironware after Hittites, blacksmiths were still considered as a distinctive people in their nations and their communities, as Katsumi Tamura notes. The fundamental role of the blacksmith is to be a tool manufacturer, regardless of the region where he belongs; he produces implements for various uses such as agriculture, fishing, hunting, was and ceremony (ritual). Ronald Webber wrote: '...He must have been an impressive figure, and he was able to produce and repair almost all the things needed for agriculture, domestic life and war'.

I would like to describe the distinct features of iron manufactures across several countries and periods with illustrations. Firstly, it is remarkable that ironwork can be seen in not only in tools and implements but also in the adornment of building in Europe. Particular types if iron used for forging is called 'wrought iron' in English, 'iI ferro battuto' in Italy, and 'kunstschmiede' in German.

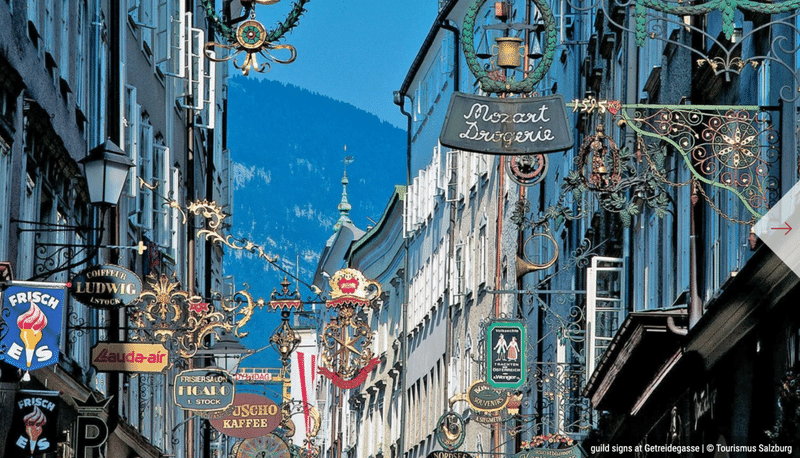

Wrought iron is not only forged iron but it iron objects have religious, ornamental, and artistic elements, Naoto Uda - Japanese artist blacksmith explains. Various techniques were developed and applied to both interiors and exteriors in several modes of architecture such as the art nouveau ironwork on Saint Cyr House designed by Gustave Strauven in 1903. Iron was also regarded as a talisman to protect against evil. Therefore, much ironware has been for a decoration of church from long time ago. There are for instance, many ornamental signs and diverse modes of building with iron on the street of Getreidegasse in Salzburg, Austria. The oldest building is built as early as in 8th century.

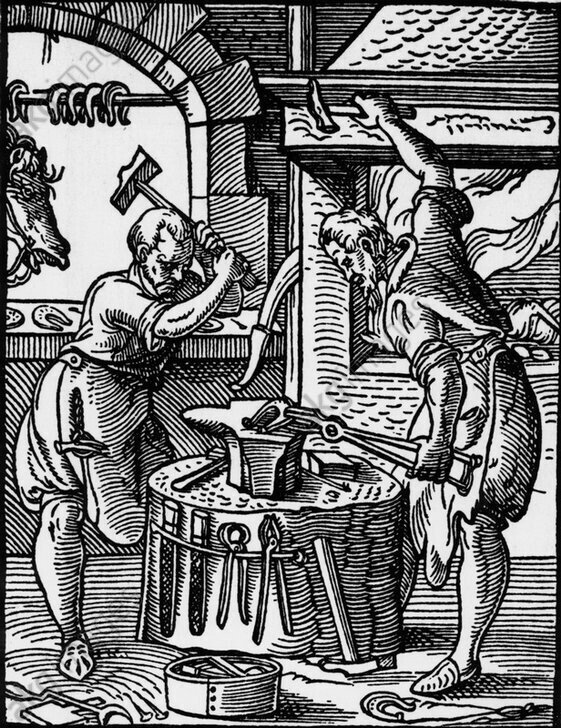

Greerlings writes that in Western Europe, iron-manufacturing techniques seems to that have developed together with architectural ornament as the basis of cathedral architecture. Forging has thus long been a main way of producing ironwork and forgers (blacksmiths) over time specialized and were transformed into specialized several forgers; farriers, locksmiths, chain smiths, nail smiths, gunsmiths, sword smiths and so on. Images of them appeared in many paintings and drawings from 12th century, the 3rd image below shows an engraving of German Farriers in 1543.

Saint Cyr House 1903, Gustave Strauven, Belgium

Getreidegasse street, Austria

Working Farriers, Hans Sachs, 1543

(Jaroslav Krejci, Anna Krejcova, Before the European Challenge, 1990)(W.F.Jackson Knight, Cumaen Gates, 1936) (Mircea Eliade, The Forge And The Crusible, 1962) (Hideo Akanuma, The Discovery of the Oldest Iron Flakes and Its Meanings, 2005) (Katsumi Tamura, Tetsu no Minzoku, 1983) (Ronald Webber, The Village Blacksmith, 1971) (Gerald K.Geerlings, Wrought Iron in Architecture: An Illustrated Survey, 1984)

Smithing In Africa

Many believe that iron manufacturing was started the Hittites and introduced to other countries include Egypt and Africa. Yet, contrary to popular belief W.E.B.Du Bois has suggested that ancient African possessed its own iron technology and introduced it to other nations: 'Gabriel de Mortillet (1883) declared Negroes the only iron users among primitive people. Some would, therefore, argue that the Negro learned it from other folk, but Andree declares that the Negro developed his own "Iron Kingdom." Schweinfurth, Von Luschan, Boaz, and others inclined to the belief that the Negroes invented the smelting of iron and passed it on to the Egyptians and to modern Europe'. The interesting issue is that experts believe that the process of iron smelting and the role of the blacksmith in some African communities has not changed through to modern times since their ancestors learned the original technique. African ironwork produces multipurpose implements such as machetes, used in hunting, farming as well as in ceremony, as well as ranges of other farming, hunting tools and arms.

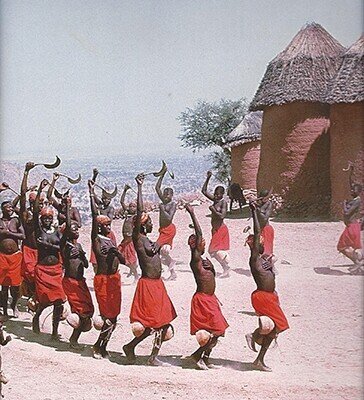

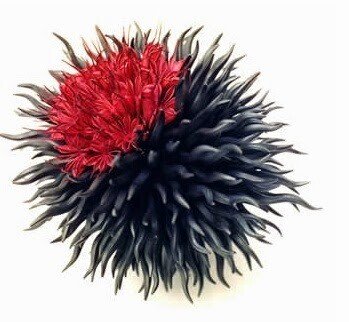

Matakam dancers by Michel Huet, The Dances of Africa.

"In the past, the women used to perform these dances after the harvest at the beginning of the dry season; they were generally intended to pay homage to the earth and the ancestors, as well as to all the women who had tended the fields, from the time of the sowing until the harvest. The pruning hooks carried by the women as they dance stand for renewed fertility and future abundant crops." - Text by Claude Savary

(W.E.B.Du Bois, The Negro, 1915)

Smithing in China

The development of iron technology was totally different between ancient Europe and ancient China. The former forged an iron into ironware, and the latter cast it. In China, the developing of casting iron technology tool place between 476 - 221 B.C., whereas it began in the 14th century A.D. in Europe. China was the first country to invent and to apply casting technology into metal and thus it called 'Motherland of casting', as Isamu Taguchi explained.

Metallurgical bellows, powered by a horizontal waterwheel, from the Chinese work of 1313 AD. (http://www.waterhistory.org/histories/waterwheels/)

Japan

The technology of iron was introduced to Japan from China by way of Korea in the Yayoi period (c.400 B.C. - 300 A.D.) as John W. Hall writes. Several group of technicians in many fields came over to Japan from Korea to instruct rice farming, making earthenware, sericulture, weaving and technology of metals. 'Tatara' method was the most important technology in the Japanese history of iron manufactures and was/is based on smelting iron from a large amount of iron sand and charcoal. The word 'Tatara' is the name of the stepping bellow, furnace, and foundry as Kurao Kubota writes. This is a recent photograph of the Tatara method of smelting.

Tatara method of smelting, Nittouho Tatara (https://tetsunomichi.gr.jp/history-and-tradition/tatara-outline/part-1/)

(Isamu Taguchi, History of Iron and Chemistry, 1988) (Kurao Kubota, The History of Japan Through Iron, 2003)

Women Blacksmiths

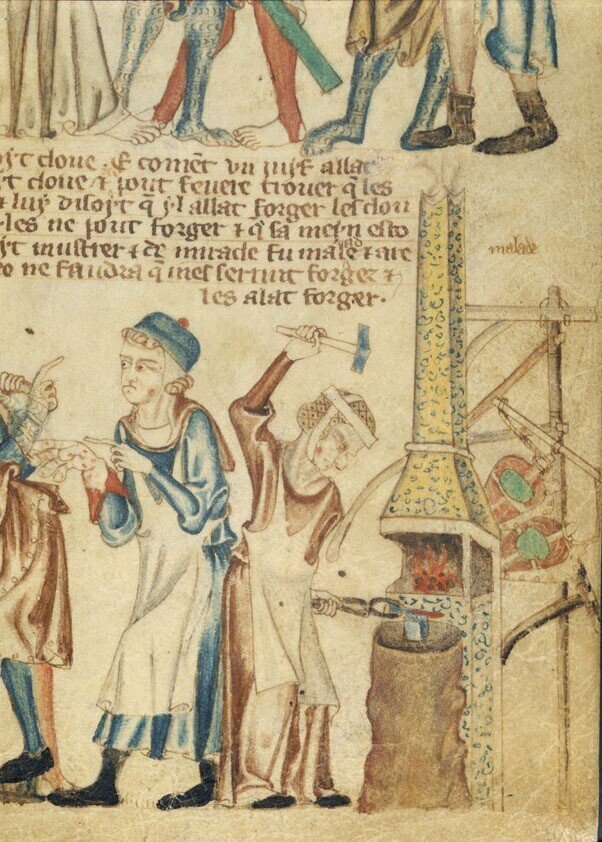

In most of the texts mentioned in my research so far, there was little mention of women blacksmiths. In the history of the blacksmith, a female blacksmith is very unusual, as most myths and visuals associated a blacksmith with a man. To be sure, forging involves completely hard physical labour. Hammers are heavy and not easy to handle. The body becomes sooty, and the smith is always face to many hazards. It is a job directly related to the strength as I found out for myself when working at the Glynde Forge. Therefore, the blacksmith has long symbolized masculinity and the job is established as a male-dominated. This image illustrates the oldest known image of a European woman blacksmith, from the Holkham Bible of about 1327-1335.

An oldest woman blacksmith in the history, The Holkham Bible Picture Book, England 1327-1335

Many women today break the rule of the male blacksmith tradition as they in general work today and the barrier of gender is gradually becoming weaker. I shall talk more about woman artist blacksmiths in chapter 4.

Chapter 2

World Myths of the Blacksmith

Blacksmithing is closely linked to the world of animism. Animism is the most ancient form of religions practice and deeply connected to people's lives, since ancient times. Animistic brief hold that everything in the Universe lives. It does not differentiate between the animate or inanimate, an idea strongly ingrained among the agricultural people. This awe of nature and its worship has been handed down from ancient times to today particularly through rituals. The worship of nature, despite the adoption of Christianity, Islam and other belief remains in these following countries; Africa, India, Nepal, Indonesia, Japan, Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, Thailand, Sweden, Philipine, Canada (Inuit), the US (Native American), and Mexico. In Japan, almost all Japanese still believe in Shinto. Even after the introduction of Buddhism, the worship of Shinto has not decayed and its related concept of animism is deeply rooted in people's daily lives and rituals.

Animism and Shamanism exist together. The role of Shama within animistic practice is to act as an intermediary between the earthly world and the realm of the spirits. Most shamanic tribes and nations regarded them to be divine people, as Levy Bruhl explains.

Significantly for this research, many scholars identifying the blacksmith as shaman 'The Yakuts claim that "smith and shaman come from the same nest", Santillana and Dechend add that: "The smith is the oldest brother of the shaman," and that amongst the Yukuts 'Concerning the Terrestrial blacksmith: the many iron pieces which belong to the costume of a shaman can be forged only by a blacksmith of the 9th generation, i.e., eight of his direct ancestors must have been in the profession. A smith who dared forge a shamanistic outfit without having those ancestors would be torn by bird-spirits.'

In Africa, the blacksmith is a multiple profession. He is a blacksmith, witch doctor (shaman), and sculptor too. In Nepal, there is a 'Shaman Blacksmith'. Blacksmiths only make the sacred Kukri (Nepalese Machete) called 'Kami', This word 'Kami' is the same word as 'God' in Japanese. In Japan there are shaman called 'Itako', and normally they are either innately or have acquired blindness.

A siberian shaman with his sacred drum, Photo by Alexander Nikolsky for Siberian Times

Old Itako during possessions, Photo by Tarou Okamoto in his book, 'Okamoto Trou ga mita Touhoku', Mainichi Shinbunsha 2002

As discussed already in chapter 1, many experts, such as Mircea Eliade and Katsumi Tamura believed that the first ironware was made by meteoric iron, 'thunderstones' or 'thunderbolt teeth' or 'God's axes'. There is no wonder that if ancient people thought this iron as a gift from heaven's god and that the blacksmith was the only one could produce an object from it, that the blacksmith was therefore seen as a special being, a medium between heaven's god and earthly people, exactly same role as a shaman.

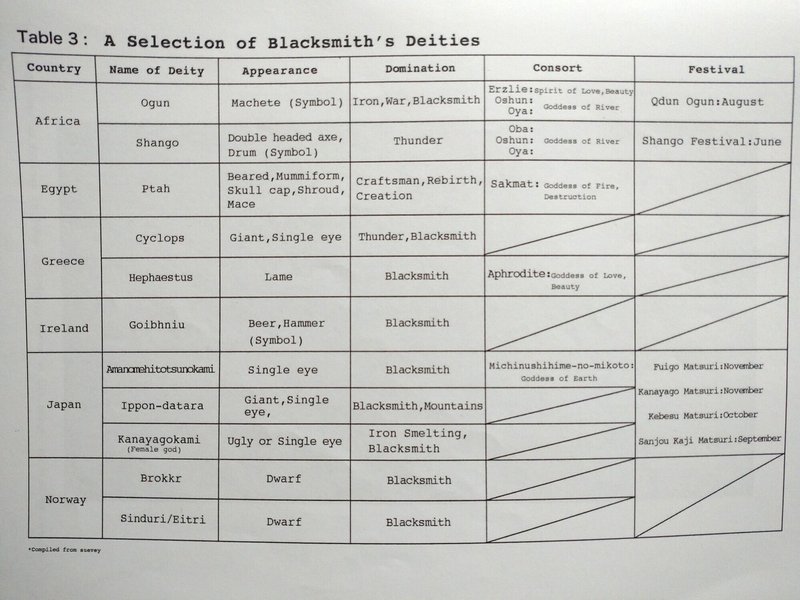

'The art of creating tools is essentially superhuman- either divine or demonic,' explains Eliade. Meteoric iron was not easily found and therefore, its value was higher than the value of gold. People eventually found iron ore: 'the mine compared to the uterus and ores to embryos'. As Eliade explains, ores were believed to be the children of the mother of mountain. These 'embryos' sacrificed their lives to be reborn at the blacksmith's heath, and through another womb again into new life. Likewise ores were also regarded as a mother herself giving a birth to a child by sacrificing her life. In fact, a certain Japanese myth is very similar to this, Eliade thought and as discussed Japanese iron-smelting tatara, means 'the womb' as well and inside of hearth. The process of extracting iron is very like a reenact of childbirth. My table 3, lists the names and characters of blacksmith deities I found in my research.

A blacksmith presides over life, death and regeneration through his work processes of deconstruction and restoration using fire. The agricultural implements forged by the blacksmith help grow abundant crops and make farmers wealthy but on the other hand, blacksmiths also forge murderous weapons. This dual character of a blacksmith was a factor that led them to be worshipped as shaman or demi-god (evil). Moreover, the rhythm of stepping bellow by the blacksmith is said to be a very similar motion to a shaman's dance step. Almost all shamans use drums for their ceremony and the sound of drum would also imitate a sound of hammering metal as Katsumi explained.

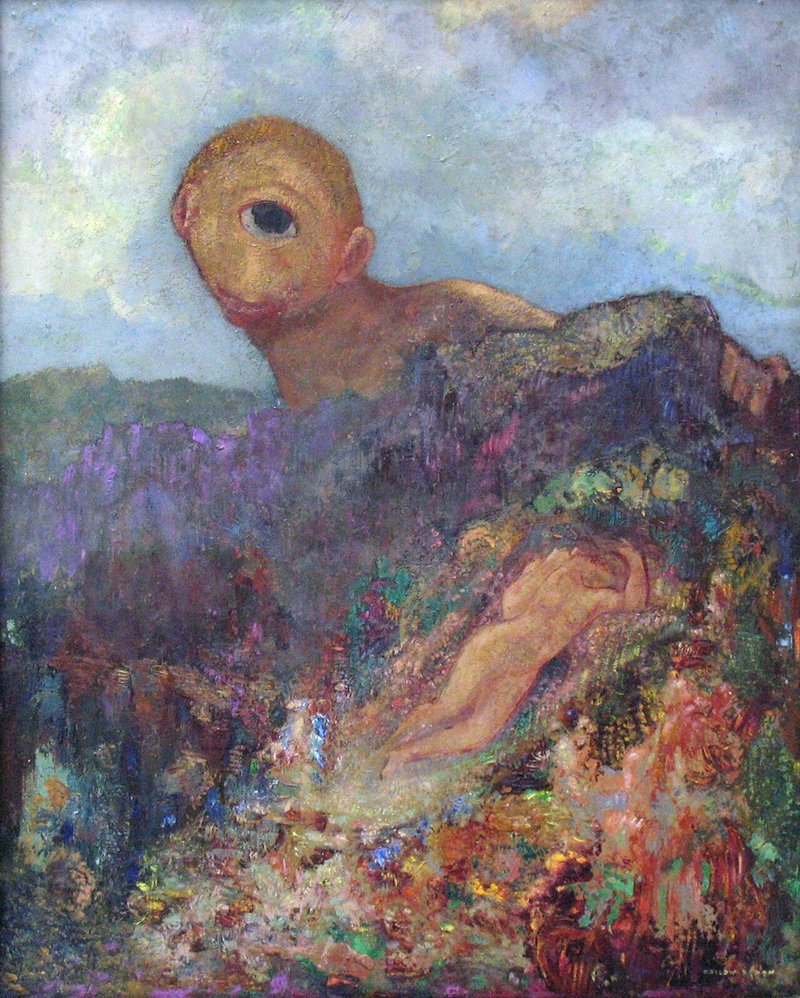

Most gods related to the blacksmith in world myths have imperfections in their bodies, such as single eye, single leg, and malformation of a body size (see table 3). The Greek god of blacksmiths, Hephaestus has a lame leg and is represented as an ugly man. Cyclops is a giant and one-eyed may regard as a god of thunder and blacksmith. The Japanese god of blacksmith Amanomehitotsunokami, (the one-eyed god of the sky), also has a single eye and is sometime described as a giant, as is Ippon a single leg.

Hephaestus (Vulcan in Roman mythology) works at his forge, Painted by Peter Paul Ruben

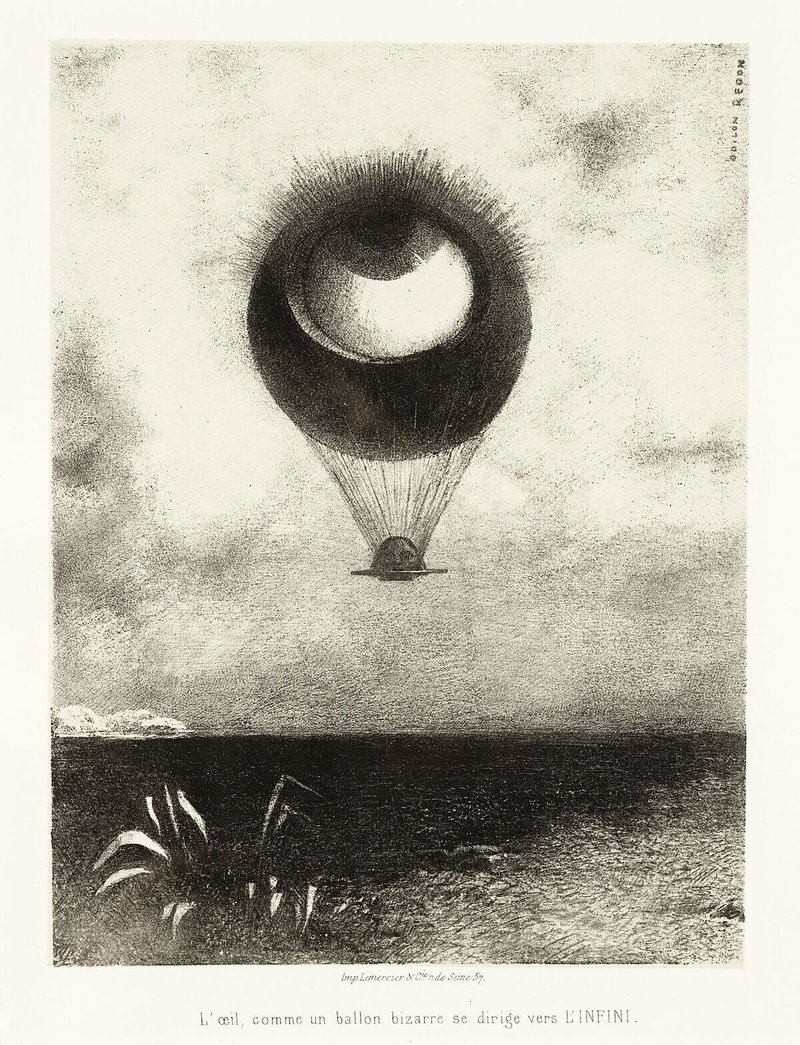

The Cyclops, Painted by Odilon Redon 1914

The Eye like a Strange Balloon Mounts Towards Infinity, Odilon Redon 1982

There is the female blacksmith god usually, called Kanayagokami in Japan and she is described as an ugly woman or one-eyed. Shigeru Fujii believed that there are several reasons that explain all of this. Firstly, it is widely believed that a blacksmith stares blight flame through one eye for a long period and becomes blind one eye finally and because he has to keep stepping bellows with one leg, he destroys it. Secondly, to keep secret the work of iron manufacturing, a blacksmith was forced to break his one leg and to ruin his one eye. Lastly, the facial skin is always exposed against the fire of hearth so his skin is burnt and becomes reddish, sooty with dirty skin.

Many gods of blacksmith also related to thunder gods such as in Africa (Shango), Greece(Cycrops), and Japan(Amanomehitotsunokami), and they are described as giant gods. In fact, one-eyed, giant god is a sky (heaven) itself; there is only on eye (sun) in the sky. Thunder is the leg of the sky (father), or even the genitals to connect to the earth (mother) to have children (ores and crops). In Japanese the words Kaminari, Ikazuchi and Inazuma, means thunder as the character of Kaminari is 'rain and field'(雷), Inazuma is 'the wife of rice'(稲妻), and 'zuchi' of Ikazuchi means 'hammer'. The connection is that the farmer used ironware to reclaim the crop from the field and grew a crop of rice after the rain and thunder. As the technology of iron and agriculture travelled all over the world, myth travelled too little by little with time, and took its root in various places. The mythology of the blacksmith is therefore completely linked to the origin of agriculture.

Table 3: A selection of Blacksmith's deities *compiled from survey*

(Yukihiro Hosaka, Japanesen Nature Woship, Western Animism - Religion and Civilization/Invitation of Non Westernized Religious Understanding, 2003)(Lucian Levy-Bruhl, Les Fonctions mentals dans les societes inferieures/ How Natives Think, 1910)(Giorgio De Santillana, Hertha Von Dechend, Hamlet's Mill, 1977)(Andras Hofer Heidelber, A Settlement And Smithy of the Blacksmiths (Kami) in Nepal,1793)(Mircea Eliade, The Forge and The Crucible, 1962)(Katsumi Tamura, Tetsu no Minzoku, 1983)(Shigeru Fujii, Medama no Michikusa, 2004)(Yoshiharu Iijima, Hitotsumekozou To Tatara, 2001)(Shuzaburou Hagiwara, Kami no Hassei, 2008)

Chapter 3

The Traditions of the Blacksmith

Blacksmithing is a very skilled and dangerous craft and needs special and specific training. In Germany a Meister (A master craftsman) was a member of a blacksmith Guild. In the European guild system, only meisters were allowed to be member in Europe the master craftsman is not only a blacksmith but belong to all hand-work professions, such as carpenter, stone mason, a craftsman in wood, bread maker, weaver, butcher, silversmith and so on. To be a master, the craftsman had to take an apprenticeship for a couple years and the became a 'Journeyman' artisan or 'Wondergesellen' right across European countries such as Germany, France and England. A below image shows German Journeymen today. There is a very similar apprentice system called 'Watari no Shokunin' (traveling craftsman) in Japan. In modern times, this master training system has declined as most handwork industry shifted to machine technology, from the development of the industrial revolution from the middle of 18th century in England.

Young German Journeymen (Wondergesellen) photo credit: Wikipedia

Although the word journeyman is an old-fashioned idea, even today in parts of Europe, young people still travel taking an apprenticeship in their specialism keeping up the rules of this system, such as wearing a particular uniform for the different professions.

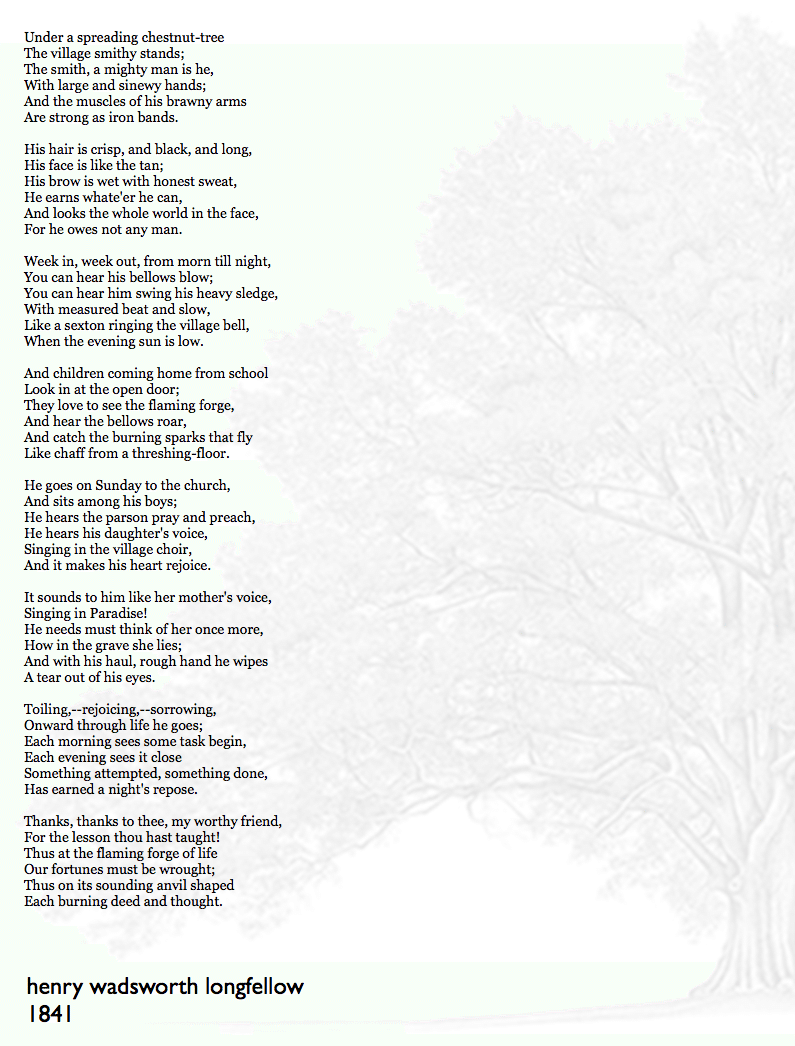

The Village blacksmith was also affected by the industrial revolution. There were blacksmiths in every town as they often appeared in poem such as 'The Village Blacksmith' by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow written in 1841 (See Table 4) . The forge at Glynde where I worked is a survivor from these days and young people are becoming interested in this old traditional profession with the traditional blacksmith.

Table 4: The Village Blacksmith

(Mitsuo Ogawa, Yonematsu Shiono, Touryou: Pass on the Skill and Train People, 2008)(C.R.Dobson, Masters and Journeymen: A Prehistory of Industrial Relations 1717-1800, 1980)

Chapter 4

Interview with Artist Blacksmith

This chapter investigates the work of three blacksmiths today, who are unusual, in that they are Artist Blacksmiths, rather than working village or industrial blacksmiths. Even more usually are women. This chapter looks at their work and their place in blacksmithing as women makers.

Naoto Uda

(Interview by e-mail, 18th November 2008) Studio ZWEI: http://www.net1.jway.ne.jp/s.zwei/

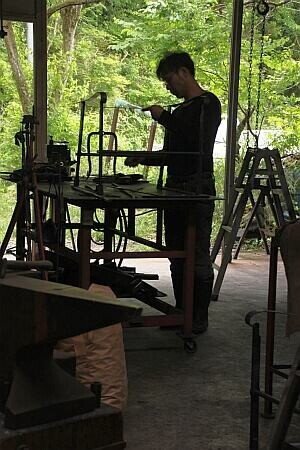

Naoto Uda at his studio in Ibaraki

Naoto Uda studied metalworking at University in Japan. After graduating he had took apprenticeships both in Japan (May 1997-April 1999) and in Germany (May 1999-August 2002), where worked at several blacksmiths. After he returned to Japan, he set up his own studio in the rural area of Ibaraki, east part of Japan. He has been awarded for several prizes in Japan, such as Ibaraki Design Selection 2007 and Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Prize 2008.

Uda stated that he learnt basic skills in casting, forging and carving. His specialism was forging, especially using copper to produce sculptural works and traditional craft pieces. He mastered iron forging to make tools for his work although this was the first opportunity he had to work at iron forging.

After graduating from the University of Industrial Arts and Design. he worked as an apprentice blacksmith in Japan. His employer had also studied in Germany so he produced a westernized style of ironwork rather than traditional Japanese products. When Uda was working there, there was no time for him to make his own art piece but even so he made some sculptural work.

Through this contact Uda became inspired by European blacksmithing. 'In Japan, the level of a blacksmithing skills as a toolmaker is very high but I felt there are only few blacksmiths produces ornamental ironwork. "Artist Blacksmith" is really rare,' writes Uda, in e-mail interview.

The fields of blacksmithing in Japan and in Europe are quite different. In Japan, blacksmithing work is generally a tool making for agriculture such as hows, sickles, spades and knives rather than anything else but in Europe more ornamental work is created and strongly connected to architecture. European blacksmithing tools are different too such as the shape of the anvil; Japanese anvil is flatten and not high while European anvil has a horn at the end.

When I asked what he felt about women blacksmiths, Uda told that he had met a woman blacksmith in Germany. 'Of course there is a physical handicap but she worked-out her own way of working tools, so she is working at an equal position with men.'

After he returned to Ibaraki, Japan, a German journeyman took apprenticeship at his place for a while. About this, Uda writes briefly 'In my opinion, he would be better to train at one place for at least one year. In the old times, blacksmithing techniques and its design was almost standardized but today in each studio, each blacksmith has their own skills, design and facilities so it is not easy to get used to that with short time training.'

It is not surprising that Uda's works represents a fusion between both German and Japanese skills and design and between sculptural and practical objects. He is the one of the few successful artist blacksmiths who successfully characteristics merged two different countries blacksmithing into one united piece.

Work of Naoto Uda: Kazou Byoubu and furnitures for his exhibition, photo credit: Naoto Uda

Japanese blacksmith working at his forge, Takanashi Seisakujyo, https://takanashissk.thebase.in/

European anvil, Photo by Ai Iijima

Junko Mori

(Text draw from BBC Radio4, Woman's hour interview, 7th November 2006) http://junkomori.com

Mori is one of the most successful Japanese female artist blacksmith but is even more famous in the UK. She studied industrial, interior and craft design / metalworking at University and worked at a welding factory in Japan for a year. After graduating she studied silversmithing and metalworking at Camberwell College of Arts London (1998-2000), and moved to the UK after that. She was short listed for a Jerwood Metal Prize in 2005.

In her time at the foundry she learned Japanese traditional blacksmithing skills from her 70 years old employer. As to the gender issue, she stated that there were another five men working with her and that "They treated me like a princess because I was only one woman working there." She became interested in British blacksmithing because of its rich history, and that is why she came to study abroad in London.

Blacksmithing is a dirty and filthy job as they work with hot metal, standing by a burning hearth, and it required a lot of stamina. However, Mori said: 'The blacksmith doesn't need to be a tall, broad-shouldered, heavy-set man but needs stamina. My boss was smaller and skinner than me but he could carry heavy steel sheet just by himself. He had an amazing stamina.'

As a woman blacksmith, she sometimes feels people's curiosity about she is not only just because she is a woman blacksmith but she is especially a Japanese woman blacksmith. 'If I go to the tool shop, everyone is looking at me with curiosity as if to say what "why are you here?" and I was struggling with that at the beginning but now I am using this opportunity as an advantage. A Japanese female blacksmith in Uk, it is seems to be generate a lot of interests. How lucky I am!'.

As written at the start of this research project, my experience at the forge at Glynde was exactly similar to the comments made in this interview by Junko Mori.

62 Organism, 2001 Junko Mori (Image from her website)

Lucy Sandys-Clarke

(Text draws from Mail interview by Chris Brooke, 11th May 2007, Yorkshire Post interview by Yvette Huddleston, 30th July 2008, and interview by e-mail, 1st December 2008) http://www.lucysandysclarke.com

Lucy Sandys-Clarke is a member of the British aristocracy but she has chosen to be a blacksmith as her career. She is not an artist blacksmith like Junko Mori but one of the only woman traditional blacksmith in Britain. Lucy confirms this and says she considers herself to be a craftsman rather than an artist. She took over the running of the village blacksmith in Dent in 2006 after serving an informal five year apprenticeship, and working with the self-taught old village blacksmith in Dent.

"I wanted to be a furniture maker but while I was looking for a suitable course I met a blacksmith in Cambria and it all started from there. And I don't think it really makes a difference being female. I just think of myself as being a blacksmith." Sandy-Clarke said in interview on e-mail.

The spirit of the old-fashioned blacksmith lives on in Lucy's smithy and her products reflect this as she uses traditional skills. She does not use any modern methods as she mentioned, "A lot of people work with metal these days," she says, "but very few people do traditional blacksmithing which is what I do. I don't use any electricity for welding - it's all done with a coke fire," She told the Yorkshire Pose.

Although it is still unusual for a blacksmith to be a woman, Lucy feels that gender is irrelevant. "There is a perception that you have to be big and muscular, but that's not necessarily true," she says a view which reflects the opinion of the blacksmiths quoted in this research.

Traditional rivet latch by Lucy Sandys-Clarke (image from her website)

Chapter 5

The role of blacksmith today

Today, the role of blacksmith is becoming harder to define especially in the advanced countries such as England, Germany and Japan. However, traditional hand-forge based blacksmiths are still surviving as shown in Lucy Snadys-Clarke's work. Whether men or women they are now in fact drawing much more attention and remain in the public eye for restoration and traditional work and now also for educational and heritage purposes. For example, Terry Tyhurst from Glynde Forge sometimes shows his craft to school children and also performs at the annual Blacksmith Fair with other blacksmiths, and organizes weekend's workshop for enthusiasts.

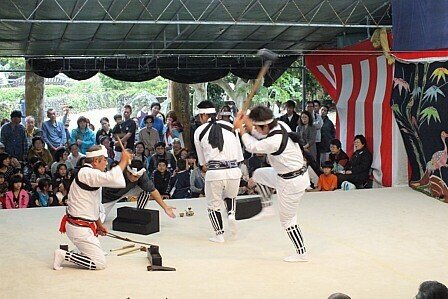

In Japan there are still many annual traditional festivals related to blacksmiths that help to transmit the craft and culture from one generation to another and help young people become interested in traditional blacksmith training. In Okinawa, a small island of Southern Japan, there is an ancient play called 'Kazagu Kyongyon' which explains that Okinawa used to import iron to make implements for agriculture from the main island of Japan because there was no iron sand or iron ores. Therefore, iron was highly valuable at that time and blacksmiths only worked when they got iron. They celebrated the day they worked and that is the basis of the story of this Kazagu Kyongyon shown in attached images that young people taking part of this play. There is another notable festival dating from almost 1000 years ago called 'Kebesu Matsuri' which takes place at the shrine in Oita, in West Japan. This festival is about a great battle between a 'Kebesu', man wearing a mask and the 'Touba', (people who have the duty to protect fire of Tatara).

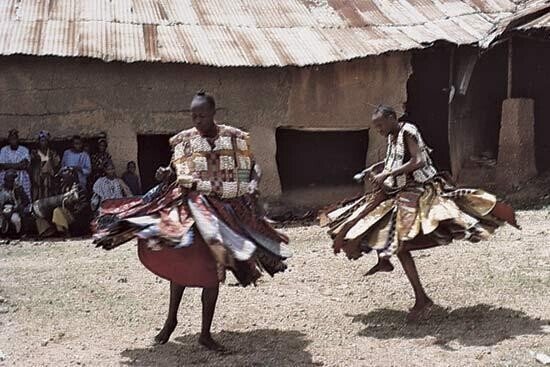

In west Nigeria, the Shango festival is celebrated every year in Yoruba communities still today. It reaches its climax after 20 days of preparation and involves sacrifices made at the shrine of the god in the compound of the hereditary priest in Lagos. The priest becomes possessed by the god, gains magical powers, eats fire and swallows gunpowder. A procession the follows him to the Oba's palace, where there is a feast.

Blacksmithing is the origin of all industries. After man found iron to create implements, people easily cut down trees, broke the ground and excavated ores. A civilization rapidly developed after the appearance of iron. The origin if today's modern convenience was a simple tool that ancient blacksmiths produced.

'Kazagu Kyongyon' Traditional play of Blacksmith in Okinawa, Japan http://tundara.blog.fc2.com/blog-entry-187.html

Kebesu Festival in Oita, Japan (A battle between Kebesu and Touba) https://inabana.com/20181003/%E5%A4%A7%E5%88%86%E7%9C%8C%E3%80%80%E7%81%AB%E3%81%AE%E7%B2%89%E8%88%9E%E3%81%86%E5%A5%87%E7%A5%AD-%E3%82%B1%E3%83%99%E3%82%B9%E7%A5%AD%E3%82%8A/

Performing a dance in honor of the god Shango, Yoruba in Nigeria, Africa (Photo from Encyclopedia Britannica)

In special festivals and processions, followers of Shango, the Yoruba god of thunder, carry dance wands, oshe shango, depicting a female devotee with Shango's symbol, the double-headed axe. http://brockbaker.pbworks.com/w/page/8688073/Yoruba%3A%20Practices%20Rituals%20and%20Festivals

My grand father was a shoemaker and also a carpenter. Blacksmith forged most of his tools such as the blade of his plane, nails and hammer. People of his generation were all makers and users, somehow had a relation to blacksmithing work. Therefore, they were also good judge of tools. However, after the industrial revolution in Japan and the rapid growth of the economy from 1955 to 1973, the numbers of blacksmiths reduced quickly like other village blacksmiths in the industrialized world. The world became no longer needed hand tools and machines such as tractors, now do many of the heavy duties. Many well-known blacksmiths are very old in Japan 70-90 years old, but they are still working at forge and still very respected. Their sons and other young people who want to be blacksmiths take an apprenticeship but the number of apprentice is not large and probably a half of all Japanese blacksmiths will be closed in decade, as Tsutomu Kakuma states.

The role of blacksmith today in my view remains as 'A great doctor of iron'. When I was working at Glynde Forge, a massive wheel for a farm tractor was brought in for welding rusted holes on the surface. I was struck by the enormity of the job but also by the fact that iron is very long life material. Once broken and worn-out, blacksmiths re-forge it again and again to produce new ironware. The users understood iron's value as did blacksmiths, and treated ironware as treasure. After work, farmers cleaned their hoes and sickles to avoid rust and took them to blacksmith to sharpen them. I today's mass produced, mass consumption culture, broken goods are thrown away. People even forgot to take care of a product, unlike the blacksmith's traditions of care, mend and re-use.

Above all today, in my opinion, the Artist Blacksmith is a modern shaman reviving life in the almost forgotten tradition of the material and spiritual value of iron. They were probably found realities that consumers can understand through both iron's aesthetic value rather than its practical value. The artwork forms created by many artist blacksmiths clearly organic in conception such as work by Junko Mori, Naoto Uda and Sam Biley whose work in shown below. They forge iron into the shape of plants to represent life in a inanimate object, presenting two antagonistic principles life and death, fragility and strength. I think that their work, as in mine, is built on their knowledge of the blacksmith's work and carries an awe of nature from ancient traditions and myths. This seems evident in the strongly visualized forms in the work of Bailey, Uda and Mori for example.

Detail of railing, Sam Bailey http://www.theartistblacksmith.co.uk/about.html

The key issue of interest that has developed out of my blacksmithing experience and the research for this text has been the opportunity to consider the worldwide blacksmithing situation and its identity as well as considering my own identity as a woman blacksmith, and a Japanese woman living in the UK. What tis study has shown is that traditional blacksmithing is definitely on the decline because of the changing circumstances of society and because few blacksmiths have any successors to follow them after they retire. In addition, although training takes many years, it is getting harder and harder to secure a career and earn a living as a blacksmith especially in advanced countries.

However, as in the training of Mori and Uda, traditional blacksmithing techniques are crossing boundaries. If the local tradition declines in one country, it may take root in another like the seed of a plant. So it incorrect to say that traditions in blacksmith are fading away, but rather that they are spreading throughout the world although in new forms and contexts, around the world, and whether made today by man or woman.

Working with Terry Tyhurst at Glynde Forge, photo by Yuko Michishita

Ai Iijima forging hot iron at Glynde Forge, Photo by Merle Moustafa http://www.merlemoustafa.com/

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?