The virus hunters who search bat caves to predict the next pandemic≒コウモリの洞窟を検索して次のパンデミックを予測するウイルスハンター

The virus hunters who search bat caves to predict the next pandemic≒コウモリの洞窟を検索して次のパンデミックを予測するウイルスハンター

https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/26/health/virus-hunters-bat-cave-coronavirus-hnk-intl/index.html

The virus hunters who search bat caves to predict the next pandemic

By Julie Zaugg, for CNN

Updated 11:36 PM EDT, Sun April 26, 2020

(CNN)Before entering the cave, the small team of scientists pull on hazmat suits, face masks and thick gloves to cover every inch of their skin. Contact with bat droppings or urine could expose them to some of the world's deadliest unknown viruses.

Equipped with headlights, they set their nets up at the entrance of the dark opening overhung with bamboo trees, which is part of a vast system of limestone caves in China's south-western Yunnan province.

The Smithsonian Institution carries out bat sampling in Myanmar and Kenya, allowing them to discover 6 new coronaviruses.

The Smithsonian Institution carries out bat sampling in Myanmar and Kenya, allowing them to discover 6 new coronaviruses.

Then they patiently wait for dusk. When the sun sets, thousands of bats fly out of the caves, looking for food -- and straight into their nets.

The scientists collect the nets and carefully put the bats to sleep with a mild anesthetic, before delicately extracting blood from a vein on their wings. "We also carry out oral and faecal swabs and gather droppings," says Peter Daszak, who presides over EcoHealth Alliance, an American NGO which specializes in detecting new viruses and pandemic prevention.

The entrance to one of the caves in a vast limestone cave system in Yunnan province, China, which Eco Health Alliance has been exploring for over 10 years.

The entrance to one of the caves in a vast limestone cave system in Yunnan province, China, which Eco Health Alliance has been exploring for over 10 years.

Daszak is a virus hunter. Over the past 10 years, he has visited over 20 countries trying to prevent the next big pandemic by searching bat caves for new pathogens. More specifically, new coronaviruses.

The findings of Daszak, and others like him, inform an open-source library of all known animal viruses, from which scientists can forecast which strains are most likely to spill over to humans, in order to ready the world for a new pandemic like Covid-19.

"We (have) collected more than 15,000 bat samples, which led to the identification of around 500 new coronaviruses," he says.

And one of those, found in a cave in China in 2013, was a possible ancestor of Covid-19.

Coronavirus research

Before the 2003 SARS epidemic, research into coronaviruses didn't attract much attention. "It wasn't seen as a sexy branch of medical research," says Wang Linfa, a virologist from Duke-NUS in Singapore, who develops the tools used to analyze the samples collected by EcoHealth Alliance.

Only two human coronaviruses had been identified back then, both discovered in the 1960s.

In 2009, Predict was founded. Funded by USAID, it is led by University of California Davis, alongside EcoHealth Alliance, the Smithsonian Institution, the Wildlife Conservation Society and Metabiota, a Californian company which has developed an epidemic tracker.

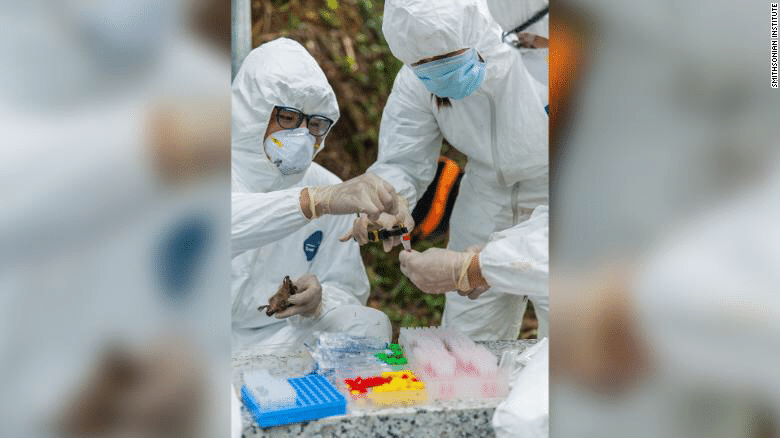

To catch the bats, EcoHealth Alliance's scientists have to set up nets at the entrance of the cave. To avoid any contact with the bats, they wear hazmat suits, a respirator and gloves.

To catch the bats, EcoHealth Alliance's scientists have to set up nets at the entrance of the cave. To avoid any contact with the bats, they wear hazmat suits, a respirator and gloves.

The initiative was tasked with identifying and responding to new zoonotic diseases -- including coronaviruses -- before they spread to humans. Over the course of its 10 years in operation, it was awarded around $200 million dollars.

Since its founding, five more human coronaviruses have been identified, including Covid-19. Daszak estimates that bats harbor up to 15,000 coronaviruses, only a few hundred of which are currently known.

Daszak's organization focuses on southwest China, more specifically on the aforementioned limestone cave system in Yunnan province, known for its large bat population.

"We targeted China initially because we were looking for the origins of SARS," he explains. "But then we realized that there were hundreds of other dangerous coronaviruses there so we decided to shift our attention to finding them."

EcoHealth Alliance's team take samples from a bat. Over the past decade, they have collected 15,000 bat samples.

EcoHealth Alliance's team take samples from a bat. Over the past decade, they have collected 15,000 bat samples.

Predict operates in 31 countries. Another team of virus hunters, belonging to the Smithsonian Institution, has started focusing on Myanmar and Kenya. "So far, we were able to identify six novel coronaviruses in Myanmar," says Suzan Murray, who leads the Smithsonian Institution's Global Health Program.

"These are areas with lots of wildlife biodiversity, a growing human population encroaching on the natural habitat, good travel networks and a large amount of livestock, which means there is a high potential for virus spillovers between species," says Dawn Zimmerman, who leads some of the Smithsonian Institution's virus sampling expeditions.

Bats to humans

Southeast Asia and China are of particular interest as large swathes of their populations make regular contact with wildlife, by hunting it, selling it -- often live -- in wet markets and eating it, according to Daszak.

After analyzing blood samples of people living near two bat caves in Jinning County, Yunnan province in 2015, Daszak's team found that 3% had antibodies for viruses normally only found in bats -- meaning they had already been exposed to them.

"They might have unknowingly contracted these pathogens and recovered or only had a few body cells infected," he says.

To make the jump to humans, coronaviruses need to be able to bind to their cell receptors, which usually requires an intermediate animal host, explains Wang. This can be a civet cat, a camel, a pangolin or another mammal closely related to humans, he said.

But they usually originate in bats, which carry an extremely high proportion of viruses capable of infecting humans, such as Marburg, Nipah, Ebola and SARS, according to Daszak, who co-authored a study in Nature on this topic in 2017.

"Because bats are flying mammals, their body is exposed to a lot of stress, which would normally generate an immune system response," he explains. "To deal with this, they have to tone down their immune systems, which in turn makes them more susceptible to viruses and capable of tolerating a higher viral load."

Bats also make up roughly 20% of all mammal species and congregate in huge colonies in crowded caves, making the spread of viruses among them more likely.

The coronavirus library

Once Daszak's team has collected their samples, they store them in liquid nitrogren and send to partner labs around the world for analysis.

"We usually choose to work with the best labs in the country and if there aren't any, we build up local capacity," says Daszak. The strands of virus DNA found in the sample are then compared to the profiles in GenBank, an open access database maintained by the US National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) containing all known human and animal viruses. That determines "if we are dealing with a new virus or not," says Zimmerman.

The answer is not always clear-cut.

"A virus is considered new if more than 20% of its DNA differs from that of known viruses," explains Supaporn Watcharaprueksadee, who studies emerging diseases, independently from Predict, in a lab linked to Chulalongkorn university in Bangkok.

Once the samples have been taken from bats, EcoHealth Alliance's scientists place the vials in liquid nitrogen and send them out to a lab to have them analyzed.

Once the samples have been taken from bats, EcoHealth Alliance's scientists place the vials in liquid nitrogen and send them out to a lab to have them analyzed.

Researchers also sometimes think they have found a new virus when it has, in fact, been spreading in a community for several years already. Less than half of all viruses causing pneumonias are identified, according to Patrick Woo, an expert on emerging diseases from Hong Kong University. Often, the patient just gets better and his case isn't investigated further, he said.

In 2005, Woo found a new coronavirus in two patients hospitalized in Hong Kong, which he called HKU1. But he subsequently discovered that the same virus had already infected patients in the US, Australia and France.

Another virus which might have spread to humans without anyone noticing is Nipah. Daszak believes that this virus, which surfaced in 1998 during an epidemic in Malaysia linked to 105 deaths, had in fact been jumping from bats to humans long before in rural areas of Bangladesh.

"Every year, there were a few outbreaks classified as aberrant measles," he explains. "We carried out a study on these patients and found that they had actually contracted Nipah virus." These transmissions went undetected because most people living in those areas were too poor to seek out medical treatment or lived too far from a hospital, he adds.

The samples he and the other Predict teams collect are meant to plug some of the gaps in this knowledge.

Covid-19

When Covid-19 appeared, Shi Zhengli, a virologist at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, immediately compared it to the database she had compiled with the 500 new coronaviruses identified by EcoHealth Alliance.

There was a hit. "The new coronavirus matched a sample taken from a horseshoe bat in a cave in Yunnan in 2013," says Daszak. "It was 96.2% identical."

That means the virus was either the ancestor of the virus causing the current epidemic or a close relative. "It is highly likely that an intermediate animal host was involved and transmitted the virus to humans, accounting for the 3.8% difference in genome," he says.

Knowing where a new virus came from and how it was transmitted to humans is a crucial piece of information. It can enable early detection of an epidemic and a timely introduction of measures to contain its spread, says Watcharaprueksadee.

In the case of Covid-19, knowing where it originated will help scientists understand how it mutated to become infectious to humans and hopefully prevent future outbreaks, said Daszak.

There is a precedent. In January 2019, Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health and EcoHealth Alliance announced they had found a bat in Liberia carrying the Zaire strain of Ebola, which caused the 2013-16 outbreak in West-Africa, meaning they had found the probable source of the epidemic which caused over 11,000 deaths.

The next big thing

Beyond providing insight into the origins of Covid-19 and Ebola, virus hunters also help to predict where the next big epidemic will emerge -- and hope to prevent it. By detailing where the viruses posing the biggest risks to humans lurk, they can map their progression and minimize transmissions, the thinking goes.

"Our team of virologists use the samples collected in the field to determine which viruses are most likely to spill over to humans and classify them according to their risk profile," says Murray.

Coronaviruses closely affiliated to SARS or MERS are especially dangerous, because they are capable of jumping to humans. "We found 50 new pathogens related to SARS alone during the course of our research," says Daszak. "It would make sense to focus our prevention efforts on these high-risk viruses."

In one cave, his team identified all the building needed to make SARS.

To catch the bats, EcoHealth Alliance's scientists have to set up nets at the entrance of the cave. To avoid any contact with the bats, they wear hazmat suits, a respirator and gloves.

To catch the bats, EcoHealth Alliance's scientists have to set up nets at the entrance of the cave. To avoid any contact with the bats, they wear hazmat suits, a respirator and gloves.

If they combined, the resulting virus would be capable of direct transmission to humans, without the need for an intermediate host, according to a paper published in PLoS Pathogens.

There are a range of preventative measures which can be taken to prevent that happening. Community education in areas with a high prevalence of dangerous viruses is especially important. "In some parts of Kenya, we have been teaching people to plug holes in their roofs to prevent bats from entering or teaching them to boil camel's milk before drinking it to kill off the pathogens," says Zimmerman.

EcoHealth Alliance has also been raising awareness about the risks of trafficking species like pangolins, which can harbor viruses, and educating locals about the need to avoid fruits a bat might have bitten into.

Bats and other wildlife are also sometimes fitted with trackers to understand patterns of transmission by analyzing their movements and how often they come into contact with livestock and humans, she adds.

The local capabilities built by Predict's teams could also play a crucial role in preventing the spread of an epidemic. "The labs we work with on the ground now all know how to identify a new pathogen," explains Zimmerman. Predict has built or reinforced about 60 labs in Asia and Africa.

This knowledge could be used to develop a vaccine or a treatment against a new pathogen.

The Smithsonian Institution carries out bat sampling in Myanmar and Kenya, allowing them to discover 6 new coronaviruses.

The Smithsonian Institution carries out bat sampling in Myanmar and Kenya, allowing them to discover 6 new coronaviruses.

"The blood samples taken from the bats contain antibodies, which they produced to fight off the virus," says Wang. "These could serve as the basis for the development of a vaccine or a plasma treatment against a new pathogen."

Just before the pandemic hit, the future of Predict was looking uncertain, as its funding was set to expire at the end of March 2020.

But Covid-19 has shown how essential the virus hunters' work is and it has now received a six-month extension worth $2.26 million, according to a press release by UC Davis.

While virus hunters have had to hang up their hazmat suits and cancel their sampling expeditions, they are providing emergency support to test for Covid-19 cases in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, as well as helping shape public health responses to the pandemic in those countries, according to a notice by UC Davis.

"We hope to get back out there again as soon as possible," says Daszak. "And then we will focus all our efforts on finding out where exactly Covid-19 came from."

コウモリの洞窟を検索して次のパンデミックを予測するウイルスハンター

Julie Zaugg著、CNN

2020年4月26日、午後11時36分EDT、日曜日に更新

(CNN)洞窟に入る前に、科学者の小さなチームが防護服、フェイスマスク、厚い手袋を着用して、皮膚の隅々まで覆います。 コウモリの糞や尿と接触すると、それらを世界で最も致命的な未知のウイルスにさらす可能性があります。

彼らはヘッドライトを装備し、中国の雲南省南西部にある石灰岩洞窟の広大なシステムの一部である竹の木で覆われた暗い開口部の入り口に網を設置しました。

スミソニアン協会はミャンマーとケニアでコウモリのサンプリングを実施し、6つの新しいコロナウイルスを発見できるようにしています。

スミソニアン協会はミャンマーとケニアでコウモリのサンプリングを実施し、6つの新しいコロナウイルスを発見できるようにしています。

それから彼らは忍耐強く夕暮れを待ちます。 太陽が沈むと、何千匹ものコウモリが洞窟から飛び出し、食べ物を探し、そしてまっすぐに網に入ります。

科学者たちは網を集め、コウモリを穏やかな麻酔で注意深く眠らせた後、翼の静脈から繊細に血液を採取しました。 「私たちはまた、口腔内および糞便の綿棒を採取し、糞を集めます」と、新しいウイルスの検出とパンデミック予防を専門とするアメリカのNGO、EcoHealth Allianceを主宰するPeter Daszakは言います。

Eco Health Allianceが10年以上にわたって探求してきた中国雲南省の広大な石灰岩洞窟システムの洞窟の1つへの入り口。

Eco Health Allianceが10年以上にわたって探求してきた中国雲南省の広大な石灰岩洞窟システムの洞窟の1つへの入り口。

Daszakはウイルスハンターです。 彼は過去10年間に20か国以上を訪れ、コウモリの洞窟で新しい病原菌を探すことで次の大流行を防ごうとしています。 より具体的には、新しいコロナウイルス。

ダザックと彼のような他の調査結果は、既知のすべての動物ウイルスのオープンソースライブラリに情報を提供します。これにより、科学者は、Covidのような新しいパンデミックに備えるために、どの株が人間に感染する可能性が最も高いかを予測できます。 -19。

「15,000を超えるコウモリのサンプルを収集しました(その結果、約500の新しいコロナウイルスが同定されました」と彼は言います。

2013年に中国の洞窟で見つかったそのうちの1つは、Covid-19の祖先の可能性がありました。

コロナウイルス研究

2003年のSARS流行以前は、コロナウイルスに関する研究はあまり注目されていませんでした。 「これは医学研究のセクシーな部門とは見なされていませんでした」とEcoHealth Allianceによって収集されたサンプルを分析するために使用されるツールを開発するシンガポールのデュークNUSのウイルス学者であるWang Linfaは言います。

人間のコロナウイルスは2つしか確認されていませんでしたが、どちらも1960年代に発見されました。

2009年にPredictが設立されました。 USAIDによって資金提供され、カリフォルニア大学デービス校、EcoHealth Alliance、スミソニアン協会、野生生物保護協会、および流行追跡システムを開発したカリフォルニアの会社Metabiotaが主導しています。

コウモリを捕まえるために、EcoHealth Allianceの科学者は洞窟の入り口にネットを設置する必要があります。 コウモリとの接触を避けるため、防護服、防毒マスク、手袋を着用します。

コウモリを捕まえるために、EcoHealth Allianceの科学者は洞窟の入り口にネットを設置する必要があります。 コウモリとの接触を避けるため、防護服、防毒マスク、手袋を着用します。

このイニシアチブは、人に伝染する前に、コロナウイルスなどの新しい人畜共通感染症を特定して対応することを使命としています。 10年間の運用期間中に、約2億ドルが授与されました。

設立以来、Covid-19を含むさらに5つのヒトコロナウイルスが確認されています。 Daszakは、コウモリは最大15,000のコロナウイルスを宿していると推定しています。

ダザックの組織は、中国南西部、より具体的には、コウモリの数が多いことで知られる雲南省の前述の石灰岩洞窟システムに焦点を当てています。

「SARSの起源を探していたので、最初は中国をターゲットにした」と彼は説明する。 「しかし、そこには他にも数百の危険なコロナウイルスが存在することがわかったので、それらを見つけることに注意を向けることにしました。」

EcoHealth Allianceのチームはコウモリからサンプルを採取します。 過去10年間で、彼らは15,000バットのサンプルを収集しました。

EcoHealth Allianceのチームはコウモリからサンプルを採取します。 過去10年間で、彼らは15,000バットのサンプルを収集しました。

Predictは31か国で事業を展開しています。 スミソニアン研究所に所属する別のウイルスハンターチームが、ミャンマーとケニアに焦点を合わせ始めました。 「これまでのところ、ミャンマーでは6つの新しいコロナウイルスを特定することができました」と、スミソニアン研究所のグローバルヘルスプログラムを率いるスザンマレーは言います。

「これらは、多くの野生生物の生物多様性、自然の生息地に侵入する人口の増加、良好な旅行ネットワーク、および大量の家畜のいる地域です。これは、種間のウイルスのスピルオーバーの可能性が高いことを意味します。 スミソニアン研究所のウイルスサンプリング遠征の一部。

コウモリから人間へ

Daszakによると、東南アジアと中国は、個体群の大規模な群れが野生動物と定期的に接触し、野生生物を狩り、販売します-多くの場合、生きている-市場でそれを食べることにより、特に興味深いです。

2015年に雲南省晋寧県の2つのコウモリ洞窟の近くに住む人々の血液サンプルを分析したところ、ダザックのチームは、3%が通常コウモリにのみ見られるウイルスに対する抗体を持っていることを発見しました-つまり、彼らはすでにコウモリにさらされていました。

「彼らは無意識のうちにこれらの病原体に感染し、回復したか、または感染した体細胞はわずかしかなかったかもしれない」と彼は言う。

人間にジャンプするためには、コロナウイルスは、通常は中間の動物宿主を必要とする細胞受容体に結合できる必要があると、王は説明します。 これは、ジャコウネコ、ラクダ、センザンコウ、または人間と密接に関係している別の哺乳類である可能性があると彼は言った。

しかし、通常はコウモリに由来し、マーブルグ、ニパ、エボラ、SARSなどの人間に感染する可能性のある非常に高い割合のウイルスを運ぶと、2017年にこのトピックに関するNatureの研究を共同執筆したDaszakによると、

「コウモリは空飛ぶ哺乳類なので、体は多くのストレスにさらされており、通常は免疫システムの反応を引き起こします」と彼は説明します。 「これに対処するために、彼らは彼らの免疫システムを弱める必要があります、それは彼らをウイルスに対してより敏感にし、より高いウイルス負荷に耐えることができるようにします。」

コウモリはまた、すべての哺乳類種の約20%を占め、混雑した洞窟の巨大なコロニーに集まり、それらの間でウイルスが蔓延する可能性が高くなります。

コロナウイルスライブラリ

ダザックのチームがサンプルを収集したら、それらを液体ニトログレンに保管し、分析のために世界中のパートナーラボに送付します。

「私たちは通常、国内で最高の研究所と協力することを選択します。それがない場合は、現地の能力を増強します」とDaszakは言います。 次に、サンプルで見つかったウイルスDNAのストランドを、米国国立バイオテクノロジー情報センター(NCBI)が保持するオープンアクセスデータベースであるGenBankのプロファイルと比較します。 これにより、「新しいウイルスに対処するかどうか」が決まります。

答えは常に明確であるとは限りません。

「ウイルスのDNAの20%以上が既知のウイルスのDNAと異なる場合、ウイルスは新しいウイルスと見なされます。

コウモリからサンプルが採取されると、EcoHealth Allianceの科学者はバイアルを液体窒素に入れ、ラボに送って分析させます。

コウモリからサンプルが採取されると、EcoHealth Allianceの科学者はバイアルを液体窒素に入れ、ラボに送って分析させます。

研究者はまた、実際には数年前からコミュニティで広がっていた新しいウイルスを発見したと考えることもあります。 香港大学の新興疾患の専門家であるパトリックウー氏によると、肺炎を引き起こすすべてのウイルスの半分未満しか同定されていません。 多くの場合、患者はただ良くなり、彼のケースはさらに調査されません、と彼は言いました。

2005年に、ウーは香港で入院した2人の患者から新しいコロナウイルスを発見し、HKU1と呼んだ。 しかし、その後、同じウイルスが米国、オーストラリア、フランスの患者にすでに感染していることを発見しました。

誰にも気付かれずに人間に広まった可能性のある別のウイルスはニパです。 ダザック氏は、1998年にマレーシアで発生した105人の死亡に関連したこのウイルスは、バングラデシュの農村地域でコウモリから人間に飛び移っていたと考えています。

「毎年、異常はしかと分類された発生がいくつかあった」と彼は説明する。 「これらの患者を対象に調査を実施したところ、実際にニパウイルスに感染していることがわかりました。」 これらの感染は検出されなかった。なぜなら、それらの地域に住んでいるほとんどの人々は医療を求めるには貧弱であるか、病院から離れすぎているからだ、と彼は付け加えた。

彼と他のPredictチームが収集するサンプルは、この知識のギャップを埋めるためのものです。

COVID-19

Covid-19が登場したとき、武漢ウイルス学研究所のウイルス学者であるShi Zhengliは、EcoHealth Allianceによって識別された500の新しいコロナウイルスを使用してコンパイルしたデータベースとすぐに比較しました。

ヒットがありました。 「新しいコロナウイルスは、2013年に雲南省の洞窟で馬蹄コウモリから採取されたサンプルと一致しました」とDaszakは言います。 「それは96.2%同一でした。」

つまり、ウイルスは現在の流行を引き起こしているウイルスの祖先か、近親者のどちらかでした。 「中間の動物宿主が関与し、ウイルスをヒトに感染させた可能性が非常に高いため、ゲノムの3.8%の違いが説明されている」と彼は言う。

新しいウイルスがどこから来て、どのようにして人間に伝染したかを知ることは、重要な情報です。 Watcharaprueksadeeは、それは流行の早期発見と、その蔓延を抑えるための対策のタイムリーな導入を可能にすることができるとWatcharaprueksadeeは言います。

Covid-19の場合、それがどこで発生したかを知ることは、それが変異して人間に感染するように変異した方法を科学者が理解し、うまくいけば将来の発生を防ぐのに役立つだろうとDaszakは言った。

先例があります。 2019年1月、コロンビア大学の公衆衛生およびEcoHealth Allianceの郵便配達員学校は、リベリアでエボラのザイール株を運ぶコウモリを発見したことを発表しました。これにより、西アフリカで2013-16年の集団発生が引き起こされました。 11,000以上の死を引き起こした流行。

次の大きい事

ウイルスハンターは、Covid-19とエボラの起源についての洞察を提供するだけでなく、次の大きな流行がどこで発生するかを予測し、それを防ぐことを望みます。 人間に最大のリスクをもたらすウイルスが潜んでいる場所を詳しく説明することで、ウイルスの進行をマッピングし、感染を最小限に抑えることができると考えられています。

「ウイルス学者の私たちのチームは、フィールドで収集されたサンプルを使用して、どのウイルスが人間にこぼれる可能性が最も高いかを判断し、それらをリスクプロファイルに従って分類します」とMurray氏は言います。

SARSまたはMERSと密接に関連しているコロナウイルスは、人間にジャンプする能力があるため、特に危険です。 「研究の過程でSARSだけに関連する50の新しい病原体を発見しました」とDaszakは言います。 「これらのハイリスクウイルスに予防努力を集中することは理にかなっています。」

1つの洞窟で、彼のチームはSARSを作るために必要なすべての建物を特定しました。

コウモリを捕まえるために、EcoHealth Allianceの科学者は洞窟の入り口にネットを設置する必要があります。 コウモリとの接触を避けるため、防護服、防毒マスク、手袋を着用します。

コウモリを捕まえるために、EcoHealth Allianceの科学者は洞窟の入り口にネットを設置する必要があります。 コウモリとの接触を避けるため、防護服、防毒マスク、手袋を着用します。

PLoS Pathogensに掲載された論文によると、それらが組み合わされた場合、中間宿主を必要とせずに、結果として生じるウイルスは人間に直接感染する可能性があります。

それを防ぐために取ることのできる予防策の範囲があります。 危険なウイルスが蔓延している地域でのコミュニティ教育は特に重要です。 「ケニアの一部の地域では、コウモリが侵入するのを防ぐために屋根の穴を塞ぐように人々に教えたり、病原菌を殺すために飲む前にラクダの牛乳を沸かすように教えたりしています」とジマーマン氏は言う。

EcoHealth Allianceはまた、ウイルスをかくまくことができるセンザンコウなどの人身売買のリスクについての意識を高め、コウモリが噛んだ果物を避ける必要性について地元の人々に教育しています。

コウモリや他の野生生物には、彼らの動きや、家畜や人間と接触する頻度を分析することで伝染のパターンを理解するためのトラッカーが設置されていることもあります。

Predictのチームによって構築されたローカル機能も、伝染病の蔓延を防ぐ上で重要な役割を果たす可能性があります。 「私たちが現場で作業している研究室では、新しい病原体を特定する方法をすべて知っています」とジマーマン氏は説明します。 Predictはアジアとアフリカに約60の研究所を建設または強化しました。

この知識は、新しい病原菌に対するワクチンや治療法の開発に使用できます。

スミソニアン協会はミャンマーとケニアでコウモリのサンプリングを実施し、6つの新しいコロナウイルスを発見できるようにしています。

スミソニアン協会はミャンマーとケニアでコウモリのサンプリングを実施し、6つの新しいコロナウイルスを発見できるようにしています。

「コウモリから採取された血液サンプルには、ウイルスを撃退するために産生された抗体が含まれています」とWang氏は述べています。 「これらは、新しい病原体に対するワクチンまたはプラズマ治療の開発の基礎として役立つ可能性があります。」

パンデミックが発生する直前、2020年3月末に資金の期限が切れるように設定されていたため、Predictの将来は不透明になりました。

しかし、UCデイビスのプレスリリースによると、ウイルスハンターの作業がいかに不可欠であるかをCovid-19が示しており、現在、226万ドル相当の6か月の延長を受けています。

ウイルスハンターは、化学防護服を掛けてサンプリングの遠征をキャンセルしなければなりませんでしたが、アフリカ、アジア、中東でのCovid-19ケースをテストするための緊急サポートを提供し、世界的なパンデミックへの公衆衛生対応の形成を支援しています。 UCデービスの通知によると、これらの国。

「私たちはできるだけ早くそこに戻ってくることを望んでいます」とダザックは言います。 「それから、Covid-19が正確にどこから来たのかを見つけることに全力を尽くします。」

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?