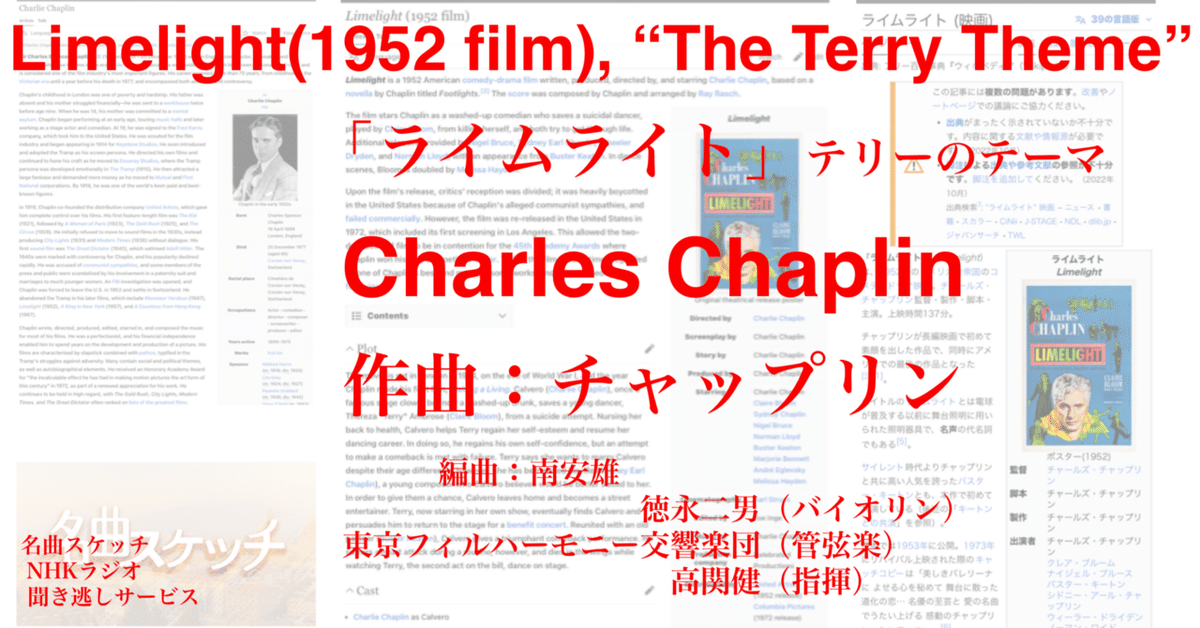

ラジオ生活:名曲スケッチ「ライムライト」

聞き逃しサービス 2024/08/06 放送

名曲スケッチ

〜

〜

「ライムライト」

[ Limelight (1952 film), The Terry Theme ]

作曲:チャップリン ( Charles Chaplin )

編曲:南安雄

徳永二男(バイオリン)

東京フィルハーモニー交響楽団(管弦楽)

高関健(指揮)

〜

開始より05分頃

〜

〜

配信終了 2024/08/13 13:45

番組情報

Google検索 URL>

https://www.google.co.jp/search?tbm=vid&hl=ja&source=hp&biw=&bih=&q=Charles_Chaplin+Limelight

Bing検索 URL> https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=Charles_Chaplin+Limelight+The_Terry_Theme

〜

〜〜

〜〜〜

☆★☆ チャップリン 「ライムライト」について【目次】☆★☆

〜〜〜

〜〜

1. 映画 「ライムライト」について

1.1 Wikipedia JA(日本版)の抜粋

1.2 Wikipedia EN(英語版)の抜粋、および、その日本語翻訳

〜〜

〜

〜〜

2. 映画制作者:チャップリン について

2.1 Wikipedia EN(英語版)の抜粋、および、その日本語翻訳

〜〜

〜

<<< 以下、参照しているWikipediaなどへのリンクはそれぞれの先頭あたりで紹介してます。>>>

〜

〜〜

1. 映画 「ライムライト」について

1.1 Wikipedia JA(日本版)の抜粋

〜〜

〜

ライムライト (映画)

Wikipedia JA(日本版) URL> https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/ライムライト_(映画)

〜

『ライムライト』(Limelight)は、1952年のアメリカ合衆国のコメディドラマ映画。チャールズ・チャップリン監督・製作・脚本・主演。上映時間137分。

チャップリンが長編映画で初めて素顔を出した作品で、同時にアメリカでの最後の作品となった。

タイトルのライムライトとは電球が普及する以前に舞台照明に用いられた照明器具で、名声の代名詞でもある。

サイレント時代よりチャップリンと共に高い人気を誇ったバスター・キートンとも、本作で初めて共演している(後述の「キートンとの共演」を参照)。

日本では1953年に公開。1973年にリバイバル上映された際のキャッチコピーは「美しきバレリーナに よせる心を秘めて 舞台に散った道化の恋… 名優の至芸と 愛の名曲でうたい上げる 感動のチャップリン・シンフォニー」。

…

【ストーリー】

イギリス一と言われた道化師のカルヴェロ。中年を過ぎてから、お酒を呑む日々を送っていた。

ある日カルヴェロは、テリーという美しいバレエの踊り子を助けた。テリーは姉が娼婦となって自分のレッスン代を払ってくれていたことを知ってから足がマヒしてしまった。すっかり失望して生きる気力を無くしていた彼女をカルヴェロは献身的に介抱し、もう一度バレエを踊らせる。

再び踊りはじめたテリーはダンサーの職を得、作曲家のネヴィルにも気に入られ新作バレエの第一ダンサーに抜擢される。一方のカルヴェロはカムバックに失敗し、逆にテリーに励まされる始末だった。

テリーに惚れ込んだネヴィルは彼女に愛を告白する。しかし彼女の想いはカルヴェロにあった。テリーはカルヴェロに結婚しようと言い出す。カルヴェロは年齢差や自らの境遇とテリーの順風満帆の現在を比べ、結婚話をばかげていると一蹴してしまう。カルヴェロは彼女の元を離れ辻音楽師へと落ちぶれてゆく。

カルヴェロと別れた後のテリーはヨーロッパ各地での興業でも絶賛される。その一方で第一次世界大戦が始まりネヴィルは出征してゆく。ロンドンに帰ったネヴィルはテリーを口説くが、彼女はまだカルヴェロのことが忘れられない。

ある日街角で偶然カルヴェロに再会したテリーは、もう一度彼を舞台に立たせるように手筈を調える。 再起の舞台で熱演するカルヴェロに観客は惜しみない拍手を送る。カルヴェロは熱演のあまり、予定よりも勢いよく舞台から転落。そのまま袖に運ばれる。転落した時に起こした心臓発作で残り僅かな時間を、鮮やかなライムライトの脚光を浴びて踊るテリーの姿を見ながら、カルヴェロは息を引取るのだった。

…

〜[上記Wikipediaより抜粋。]

〜

〜〜

1. 映画「ライムライト」について

1.2 Wikipedia EN(英語版)の抜粋、および、その日本語翻訳

〜〜

〜

Limelight (1952 film)

Wikipedia EN(英語版) URL> https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limelight_(1952_film)

〜

Limelight is a 1952 American comedy-drama film written, produced, directed by, and starring Charlie Chaplin, based on a novella by Chaplin titled Footlights. The score was composed by Chaplin and arranged by Ray Rasch.

The film stars Chaplin as a washed-up comedian who saves a suicidal dancer, played by Claire Bloom, from killing herself, and both try to get through life. Additional roles are provided by Nigel Bruce, Sydney Earl Chaplin, Wheeler Dryden, and Norman Lloyd, with an appearance from Buster Keaton. In dance scenes, Bloom is doubled by Melissa Hayden.

Upon the film's release, critics' reception was divided; it was heavily boycotted in the United States because of Chaplin's alleged communist sympathies, and failed commercially. However, the film was re-released in the United States in 1972, which included its first screening in Los Angeles. This allowed the two-decades-old film to be in contention for the 45th Academy Awards where Chaplin won his only competitive Oscar. Today, the film is sometimes regarded as one of Chaplin's best and most personal works, and has attained a cult following.

…

【Plot】

The movie is set in London in 1914, on the eve of World War I, and the year Chaplin made his first film, Making a Living. Calvero (Charlie Chaplin), once a famous stage clown, but now a washed-up drunk, saves a young dancer, Thereza "Terry" Ambrose (Claire Bloom), from a suicide attempt. Nursing her back to health, Calvero helps Terry regain her self-esteem and resume her dancing career. In doing so, he regains his own self-confidence, but an attempt to make a comeback is met with failure. Terry says she wants to marry Calvero despite their age difference; however, she has befriended Neville (Sydney Earl Chaplin), a young composer who Calvero believes would be better suited to her. In order to give them a chance, Calvero leaves home and becomes a street entertainer. Terry, now starring in her own show, eventually finds Calvero and persuades him to return to the stage for a benefit concert. Reunited with an old partner (Buster Keaton), Calvero gives a triumphant comeback performance. He suffers a heart attack during a routine, however, and dies in the wings while watching Terry, the second act on the bill, dance on stage.

…

【Cast】

・Charlie Chaplin as Calvero

・Claire Bloom as Thereza "Terry" Embrose

・Nigel Bruce as Postant

・Buster Keaton as Calvero's partner

・Sydney Earl Chaplin as Ernest Neville

・Norman Lloyd as Bodalink

・André Eglevsky as Male Ballet Dancer

・Marjorie Bennett as Mrs. Alsop

・Wheeler Dryden as Thereza's doctor and Old Ballet Dancer

・Melissa Hayden as Terry's dance double

・Barry Bernard as John Redfern

・Stapleton Kent as Claudius (scene cut for worldwide release)

・Mollie Glessing as Maid

・Leonard Mudie as Calvero's Doctor

・Snub Pollard as Street Musician

・Geraldine Chaplin as Little Girl in opening scene (uncredited)

・Josephine Chaplin as Child in opening scene (uncredited)

・Michael Chaplin as Child in opening scene (uncredited)

・Charles Chaplin III as Clown (uncredited)

Cyril Delevanti as Griffin — a Clown (uncredited)

・Oona O'Neill as Extra (Thereza's double in one episode, uncredited)

・Eric Wilton as Major Domo at Dinner (uncredited)

…

【Music】

The instrumental theme to the film, composed by Chaplin and titled "The Terry Theme", was arranged for 40-piece orchestra with a large string section by Leon Young for Frank Chacksfield and issued by Decca Records in 1953. This disc won Chacksfield a gold disc in the United States, and in the United Kingdom, where it reached No. 2 in the UK Singles Chart, and won him the NME award as 'Record of the Year'. It spent eight weeks at No. 2 (an all-time UK chart record), and in all thirteen weeks in the top five chart positions With added lyrics by Geoff Parsons and John Turner, the theme was turned into a popular and often-covered song as "Eternally".

In 1973, over 20 years after the film's first release, Chaplin and his musical collaborators Raymond Rasch and Larry Russell were awarded an Oscar for Best Original Dramatic Score. In the case of Larry Russell, JazzWax journalist Marc Myers has written that this was a case of mistaken identity and Russell Garcia was the actual composer who should have been awarded the 1972 Oscar. Larry Russell's family denies the report. Regardless, it was the only competitive Academy Award that Chaplin ever received (he had previously received two Honorary Oscars).

…

〜[Excerpt from above Wikipedia.]

〜[上記Wikipediaの日本語翻訳は次の通り。翻訳にはアプリ「DeepL」を使用。]

〜

『ライムライト』(原題:Limelight)は、チャップリンの小説『フットライツ』(原題:Footlights)を原作に、チャップリンが脚本、製作、監督、主演を務めた1952年のアメリカのコメディ・ドラマ映画。 音楽はチャップリン作曲、レイ・ラッシュ編曲。

主演のチャップリンは、クレア・ブルーム演じる自殺願望のあるダンサーを自殺から救い、共に人生を生き抜こうとする、落ちぶれたコメディアン役。 ナイジェル・ブルース、シドニー・アール・チャップリン、ウィーラー・ドライデン、ノーマン・ロイドが脇を固め、バスター・キートンも出演している。 ダンスシーンでは、メリッサ・ヘイデンがブルームの代役を務める。

チャップリンが共産主義にシンパシーを抱いているとされたため、アメリカでは大々的にボイコットされ、商業的にも失敗した。 しかし、この映画は1972年にアメリカで再公開され、ロサンゼルスで初めて上映された。 これにより、20年前の作品が第45回アカデミー賞の候補となり、チャップリンは唯一のオスカーを獲得した。 今日、この映画はチャップリンの最高傑作かつ最も個人的な作品のひとつとみなされることもあり、カルト的な人気を博している。

…

【プロット】

映画の舞台は第一次世界大戦前夜の1914年のロンドンで、チャップリンが処女作『メイキング・ア・リヴィング』を撮った年である。 かつては有名な道化師だったが、今は飲んだくれのカルヴェロ(チャーリー・チャップリン)は、若いダンサー、テレーザ・"テリー"・アンブローズ(クレア・ブルーム)を自殺未遂から救う。 彼女を健康な状態に回復させたカルヴェロは、テリーが自尊心を取り戻し、ダンスのキャリアを再開するのを助ける。 そうすることでカルヴェロ自身も自信を取り戻すが、カムバックを試みるも失敗に終わる。 テリーは、年の差はあってもカルヴェロと結婚したいと言うが、彼女はカルヴェロが彼女にふさわしいと考える若い作曲家ネヴィル(シドニー・アール・チャップリン)と親しくなっていた。 2人にチャンスを与えるため、カルヴェロは家を出て大道芸人になる。 自分のショーに出演するようになったテリーは、やがてカルヴェロを見つけ、慈善コンサートのためにステージに戻るよう説得する。 昔のパートナー(バスター・キートン)と再会したカルヴェロは、凱旋公演を行う。 しかし彼はルーティン中に心臓発作を起こし、2番目に出演したテリーがステージで踊るのを見ている間に客席で息を引き取る。

…

【キャスト】

・カルヴェロ役:チャーリー・チャップリン

・クレア・ブルーム(テレーザ・"テリー"・エンブローズ役

・ナイジェル・ブルース(ポスタント役

・バスター・キートン(カルヴェロのパートナー役

・アーネスト・ネヴィル役:シドニー・アール・チャップリン

・ボダリンク役:ノーマン・ロイド

・男性バレエダンサー役:アンドレ・エグレフスキー

・アルソップ夫人役:マージョリー・ベネット

・ウィーラー・ドライデン:テレーザの主治医、老バレエダンサー役

・テリーのダンス・ダブル役 メリッサ・ヘイデン

・ジョン・レッドファーン役:バリー・バーナード

・クローディアス役:ステイプルトン・ケント(世界公開のためシーンカット)

・モリー・グレッシング(メイド役

・カルヴェロの医師役レナード・マディー

・ストリート・ミュージシャン役:スナブ・ポラード

・ジェラルディン・チャップリン:オープニングの少女役(クレジットなし)

・ジョセフィン・チャップリン(冒頭の子供役)(クレジットなし

・マイケル・チャップリン:冒頭の子供役(クレジットなし)

・チャールズ・チャップリン3世(ピエロ役)(クレジットなし

・シリル・デレヴァンディ:グリフィン(ピエロ)役(クレジットなし

・エキストラ役のオナ・オニール(1話ではテレーザの替え玉、クレジットなし)

・エリック・ウィルトン/ドーモ少佐役(クレジットなし)

…

【音楽】

チャップリンが作曲し、"The Terry Theme "と題されたこの映画のインストゥルメンタル・テーマは、レオン・ヤングがフランク・チャックスフィールドのために大編成の弦楽セクションを伴う40人編成のオーケストラ用に編曲し、1953年にデッカ・レコードから発売された。 このディスクは、チャックスフィールドにアメリカでゴールド・ディスクを獲得させ、イギリスではUKシングル・チャートで2位を獲得し、NME賞の「レコード・オブ・ザ・イヤー」を受賞した。 ジェフ・パーソンズとジョン・ターナーによる歌詞が付け足され、テーマは「Eternally」として人気曲となり、よくカバーされた。

映画の初公開から20年以上経った1973年、チャップリンと彼の音楽協力者であるレイモンド・ラッシュとラリー・ラッセルは、アカデミー賞の作曲賞を受賞した。 ラリー・ラッセルの場合、JazzWaxのジャーナリストであるマーク・マイヤーズは、これは人違いであり、ラッセル・ガルシアこそが1972年のオスカーを受賞すべき作曲家であったと書いている。 ラリー・ラッセルの家族はこの報道を否定している。 いずれにせよ、この賞はチャップリンが受賞した唯一のアカデミー賞である(それ以前に彼は2つの名誉賞を受賞している)。

…

〜

〜

〜〜

2. 映画制作者:チャップリン について

2.1 Wikipedia EN(英語版)の抜粋、および、その日本語翻訳

〜〜

〜

Wikipedia EN(英語版) URL> https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Chaplin

〜

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin KBE (16 April 1889 – 25 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is considered one of the film industry's most important figures. His career spanned more than 75 years, from childhood in the Victorian era until a year before his death in 1977, and encompassed both adulation and controversy.

…

【Filmmaking】

《》Influences

Chaplin believed his first influence to be his mother, who entertained him as a child by sitting at the window and mimicking passers-by: "it was through watching her that I learned not only how to express emotions with my hands and face, but also how to observe and study people." Chaplin's early years in music hall allowed him to see stage comedians at work; he also attended the Christmas pantomimes at Drury Lane, where he studied the art of clowning through performers like Dan Leno. Chaplin's years with the Fred Karno company had a formative effect on him as an actor and filmmaker. Simon Louvish writes that the company was his "training ground", and it was here that Chaplin learned to vary the pace of his comedy. The concept of mixing pathos with slapstick was learnt from Karno,[al] who also used elements of absurdity that became familiar in Chaplin's gags. From the film industry, Chaplin drew upon the work of the French comedian Max Linder, whose films he greatly admired. In developing the Tramp costume and persona, he was likely inspired by the American vaudeville scene, where tramp characters were common.

…

《》Method

Chaplin never spoke more than cursorily about his filmmaking methods, claiming such a thing would be tantamount to a magician spoiling his own illusion. Little was known about his working process throughout his lifetime, but research from film historians – particularly the findings of Kevin Brownlow and David Gill that were presented in the three-part documentary Unknown Chaplin (1983) – has since revealed his unique working method.

Until he began making spoken dialogue films with The Great Dictator (1940), Chaplin never shot from a completed script. Many of his early films began with only a vague premise, for example "Charlie enters a health spa" or "Charlie works in a pawn shop". He then had sets constructed and worked with his stock company to improvise gags and "business" using them, almost always working the ideas out on film. As ideas were accepted and discarded, a narrative structure would emerge, frequently requiring Chaplin to reshoot an already-completed scene that might have otherwise contradicted the story. From A Woman of Paris (1923) onward Chaplin began the filming process with a prepared plot, but Robinson writes that every film up to Modern Times (1936) "went through many metamorphoses and permutations before the story took its final form".

Producing films in this manner meant Chaplin took longer to complete his pictures than almost any other filmmaker at the time. If he was out of ideas, he often took a break from the shoot, which could last for days, while keeping the studio ready for when inspiration returned. Delaying the process further was Chaplin's rigorous perfectionism. According to his friend Ivor Montagu, "nothing but perfection would be right" for the filmmaker. Because he personally funded his films, Chaplin was at liberty to strive for this goal and shoot as many takes as he wished. The number was often excessive, for instance 53 takes for every finished take in The Kid (1921). For The Immigrant (1917), a 20-minute short, Chaplin shot 40,000 feet of film – enough for a feature-length.

〜…〜

No other filmmaker ever so completely dominated every aspect of the work, did every job. If he could have done so, Chaplin would have played every role and (as his son Sydney humorously but perceptively observed) sewn every costume.

— Chaplin biographer David Robinson

〜…〜

Describing his working method as "sheer perseverance to the point of madness", Chaplin would be completely consumed by the production of a picture. Robinson writes that even in Chaplin's later years, his work continued "to take precedence over everything and everyone else". The combination of story improvisation and relentless perfectionism – which resulted in days of effort and thousands of feet of film being wasted, all at enormous expense – often proved taxing for Chaplin who, in frustration, would lash out at his actors and crew.

Chaplin exercised complete control over his pictures, to the extent that he would act out the other roles for his cast, expecting them to imitate him exactly. He personally edited all of his films, trawling through the large amounts of footage to create the exact picture he wanted. As a result of his complete independence, he was identified by the film historian Andrew Sarris as one of the first auteur filmmakers. Chaplin did receive help from his long-time cinematographer Roland Totheroh, brother Sydney Chaplin, and various assistant directors such as Harry Crocker and Charles Reisner.

…

《》Style and themes

While Chaplin's comedic style is broadly defined as slapstick, it is considered restrained and intelligent, with the film historian Philip Kemp describing his work as a mix of "deft, balletic physical comedy and thoughtful, situation-based gags". Chaplin diverged from conventional slapstick by slowing the pace and exhausting each scene of its comic potential, with more focus on developing the viewer's relationship to the characters. Unlike conventional slapstick comedies, Robinson states that the comic moments in Chaplin's films centre on the Tramp's attitude to the things happening to him: the humour does not come from the Tramp bumping into a tree, but from his lifting his hat to the tree in apology. Dan Kamin writes that Chaplin's "quirky mannerisms" and "serious demeanour in the midst of slapstick action" are other key aspects of his comedy, while the surreal transformation of objects and the employment of in-camera trickery are also common features. His signature style consisted of gestural idiosyncrasies like askew derby hat, drooping shoulders, deflated chest and dangling arms and tilted back pelvis to enrich the comic persona of his 'tramp' character. His shabby but neat clothing and incessant grooming behaviour along with his geometrical walk and movement gave his onscreen characters a puppet-like quality.

Chaplin's silent films typically follow the Tramp's efforts to survive in a hostile world. The character lives in poverty and is frequently treated badly, but remains kind and upbeat; defying his social position, he strives to be seen as a gentleman. As Chaplin said in 1925, "The whole point of the Little Fellow is that no matter how down on his ass he is, no matter how well the jackals succeed in tearing him apart, he's still a man of dignity." The Tramp defies authority figures and "gives as good as he gets", leading Robinson and Louvish to see him as a representative for the underprivileged – an "everyman turned heroic saviour". Hansmeyer notes that several of Chaplin's films end with "the homeless and lonely Tramp [walking] optimistically ... into the sunset ... to continue his journey."

It is paradoxical that tragedy stimulates the spirit of ridicule ... ridicule, I suppose, is an attitude of defiance; we must laugh in the face of our helplessness against the forces of nature – or go insane.

— Charlie Chaplin, explaining why his comedies often make fun of tragic circumstances

The infusion of pathos is a well-known aspect of Chaplin's work, and Larcher notes his reputation for "[inducing] laughter and tears". Sentimentality in his films comes from a variety of sources, with Louvish pinpointing "personal failure, society's strictures, economic disaster, and the elements". Chaplin sometimes drew on tragic events when creating his films, as in the case of The Gold Rush (1925), which was inspired by the fate of the Donner Party. Constance B. Kuriyama has identified serious underlying themes in the early comedies, such as greed (The Gold Rush) and loss (The Kid). Chaplin also touched on controversial issues: immigration (The Immigrant, 1917); illegitimacy (The Kid, 1921); and drug use (Easy Street, 1917). He often explored these topics ironically, making comedy out of suffering.

Social commentary was a feature of Chaplin's films from early in his career, as he portrayed the underdog in a sympathetic light and highlighted the difficulties of the poor. Later, as he developed a keen interest in economics and felt obliged to publicise his views, Chaplin began incorporating overtly political messages into his films. Modern Times (1936) depicted factory workers in dismal conditions, The Great Dictator (1940) parodied Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini and ended in a speech against nationalism, Monsieur Verdoux (1947) criticised war and capitalism, and A King in New York (1957) attacked McCarthyism.

Several of Chaplin's films incorporate autobiographical elements, and the psychologist Sigmund Freud believed that Chaplin "always plays only himself as he was in his dismal youth". The Kid is thought to reflect Chaplin's childhood trauma of being sent into an orphanage, the main characters in Limelight (1952) contain elements from the lives of his parents, and A King in New York references Chaplin's experiences of being shunned by the United States. Many of his sets, especially in street scenes, bear a strong similarity to Kennington, where he grew up. Stephen M. Weissman has argued that Chaplin's problematic relationship with his mentally ill mother was often reflected in his female characters and the Tramp's desire to save them.

Regarding the structure of Chaplin's films, the scholar Gerald Mast sees them as consisting of sketches tied together by the same theme and setting, rather than having a tightly unified storyline. Visually, his films are simple and economic, with scenes portrayed as if set on a stage. His approach to filming was described by the art director Eugène Lourié: "Chaplin did not think in 'artistic' images when he was shooting. He believed that action is the main thing. The camera is there to photograph the actors". In his autobiography, Chaplin wrote, "Simplicity is best ... pompous effects slow up action, are boring and unpleasant ... The camera should not intrude." This approach has prompted criticism, since the 1940s, for being "old fashioned", while the film scholar Donald McCaffrey sees it as an indication that Chaplin never completely understood film as a medium. Kamin, however, comments that Chaplin's comedic talent would not be enough to remain funny on screen if he did not have an "ability to conceive and direct scenes specifically for the film medium".

…

《》Composing

Chaplin developed a passion for music as a child and taught himself to play the piano, violin, and cello. He considered the musical accompaniment of a film to be important, and from A Woman of Paris onwards he took an increasing interest in this area. With the advent of sound technology, Chaplin began using a synchronised orchestral soundtrack – composed by himself – for City Lights (1931). He thereafter composed the scores for all of his films, and from the late 1950s to his death, he scored all of his silent features and some of his short films.

As Chaplin was not a trained musician, he could not read sheet music and needed the help of professional composers, such as David Raksin, Raymond Rasch and Eric James, when creating his scores. Musical directors were employed to oversee the recording process, such as Alfred Newman for City Lights. Although some critics have claimed that credit for his film music should be given to the composers who worked with him, Raksin – who worked with Chaplin on Modern Times – stressed Chaplin's creative position and active participation in the composing process. This process, which could take months, would start with Chaplin describing to the composer(s) exactly what he wanted and singing or playing tunes he had improvised on the piano. These tunes were then developed further in a close collaboration among the composer(s) and Chaplin. According to film historian Jeffrey Vance, "although he relied upon associates to arrange varied and complex instrumentation, the musical imperative is his, and not a note in a Chaplin musical score was placed there without his assent."

Chaplin's compositions produced three popular songs. "Smile", composed originally for Modern Times (1936) and later set to lyrics by John Turner and Geoffrey Parsons, was a hit for Nat King Cole in 1954. For Limelight, Chaplin composed "Terry's Theme", which was popularised by Jimmy Young as "Eternally" (1952). Finally, "This Is My Song", performed by Petula Clark for A Countess from Hong Kong (1967), reached number one on the UK and other European charts. Chaplin also received his only competitive Oscar for his composition work, as the Limelight theme won an Academy Award for Best Original Score in 1973 following the film's re-release.

…

〜[Excerpt from above Wikipedia.]

〜[上記Wikipediaの日本語翻訳は次の通り。翻訳にはアプリ「DeepL」を使用。]

〜

サー・チャールズ・スペンサー・チャップリン KBE(1889年4月16日 - 1977年12月25日)は、サイレント映画の時代に名声を高めたイギリスの喜劇俳優、映画監督、作曲家である。 スクリーンに登場する「不逞の輩(トランプ)」によって世界的なアイコンとなった彼は、映画界で最も重要な人物の一人とみなされている。 彼のキャリアは、ヴィクトリア朝時代の幼少期から1977年に亡くなる1年前までの75年以上に及び、喝采と物議を醸した。

…

【映画製作】

《》影響

手や顔で感情を表現する方法だけでなく、人を観察し、研究する方法も学んだのは、母親を見ていたからだ」。 また、ドラリー・レーンのクリスマス・パントマイムにも参加し、ダン・レノのようなパフォーマーから道化の技術を学んだ。 チャップリンがフレッド・カルノ劇団で過ごした年月は、俳優として、また映画監督としての彼に形成的な影響を与えた。 サイモン・ルーヴィッシュは、カンパニーは彼の「修行の場」であり、チャップリンはここで喜劇のペースに変化をつけることを学んだと書いている。 ペーソスとスラップスティックを混ぜるというコンセプトはカルノから学んだものであり[al]、カルノはチャップリンのギャグでおなじみとなった不条理の要素も用いていた。 映画界では、チャップリンはフランスのコメディアン、マックス・リンダーの作品を参考にした。 トランプのコスチュームとペルソナを開発する際、彼はトランプのキャラクターが一般的であったアメリカのボードヴィル・シーンにインスパイアされたと思われる。

…

《》 方法

チャップリンは映画製作の方法について、手品師が自分のイリュージョンを台無しにするようなものだとして、ざっくばらんにしか語らなかった。 しかし、映画史家の研究、特にケヴィン・ブラウンローとデヴィッド・ギルの発見は、3部構成のドキュメンタリー『Unknown Chaplin』(1983年)で紹介され、その後、彼のユニークな作業方法が明らかになった。

『偉大なる独裁者』(1940年)で台詞映画を撮り始めるまで、チャップリンは完成した脚本から撮影することはなかった。 初期の作品の多くは、「チャーリーが健康ランドに入る」「チャーリーが質屋で働く」といった漠然とした前提だけで始まった。 その後、彼はセットを作り、ストックカンパニーと協力して即興でギャグや "ビジネス "を考え、ほとんどの場合、そのアイデアをフィルムに落とし込んでいった。 アイデアが採用されたり破棄されたりするうちに、物語の構造が浮かび上がってきて、チャップリンがすでに完成しているシーンを撮り直さなければならなくなることもしばしばあった。 巴里の女』(1923年)以降、チャップリンは用意されたプロットで撮影を始めたが、ロビンソンは『モダン・タイムス』(1936年)までの全作品について、「物語が最終的な形になるまでには、何度も変容と順列を繰り返した」と書いている。

このような方法で映画を製作したため、チャップリンは当時、他のどの映画監督よりも完成までに時間がかかった。 アイデアがなくなると、彼はしばしば撮影を休み、それが何日も続くこともあった。 チャップリンの厳格な完璧主義は、このプロセスをさらに遅らせた。 友人のアイヴォア・モンタグによれば、この映画監督にとって「完璧でなければ正しくない」のだという。 チャップリンは個人的に資金を提供していたため、この目標に向かって自由に努力し、望むだけ多くのテイクを撮影することができた。 例えば、『キッド』(1921年)では1テイク終わるごとに53テイクを撮るなど、その数はしばしば過剰だった。 20分の短編『移民』(1917年)では、チャップリンは長編1本分の40,000フィートのフィルムを撮影した。

〜...〜

これほど作品のあらゆる面を完全に支配し、あらゆる仕事をこなした映画監督は他にいない。 もしそうすることができたなら、チャップリンはあらゆる役を演じ、(息子のシドニーがユーモラスに、しかし鋭く観察したように)あらゆる衣装を縫っただろう。

- チャップリンの伝記作家、デヴィッド・ロビンソン

〜...〜

彼の仕事ぶりを "狂気ともいえるほどの忍耐 "と表現するように、チャップリンは映画制作に没頭していた。 ロビンソンは、チャップリンの晩年でさえ、彼の仕事は「他のすべて、そして誰よりも優先され続けた」と書いている。 即興的なストーリーと執拗な完璧主義の組み合わせは、何日もの労力と何千フィートものフィルムを無駄にし、そのすべてが莫大な費用となり、チャップリンにとってしばしば負担となった。

チャップリンは自分の映画を完全にコントロールし、キャストが自分の真似をするのを期待して、他の役を演じてみせるほどだった。 チャップリンはすべての作品を自ら編集し、膨大な量の映像の中から自分の望む映像を作り上げた。 その完全な独立性から、映画史家のアンドリュー・サリスは、チャップリンを最初の作家的映画作家のひとりと評価した。 チャップリンは、長年の撮影監督であるローランド・トセロー、弟のシドニー・チャップリン、そしてハリー・クロッカーやチャールズ・ライズナーといった様々な助監督の助けを借りた。

…

《》 スタイルとテーマ

映画史家のフィリップ・ケンプは、チャップリンの作品を「巧みでバレエのような肉体派コメディと、思慮深く状況に基づいたギャグのミックス」と評している。 チャップリンは従来のスラップスティックとは一線を画し、テンポを遅くし、各シーンのコミカルな可能性を枯渇させ、登場人物と観客の関係を発展させることに重点を置いた。 従来のスラップスティック・コメディとは異なり、Robinsonは、チャップリンの映画のコミカルな瞬間は、彼に起こる出来事に対する不逞の男の態度にあると述べている。 ダン・カミンは、チャップリンの「風変わりな物言い」と「ドタバタアクションの中の真剣な態度」が彼の喜劇の他の重要な側面であり、物体の超現実的な変化とカメラ内のトリックの使用も共通の特徴であると書いている。 彼の特徴的なスタイルは、斜めに傾いたダービーハット、垂れ下がった肩、膨らんだ胸、ぶら下がった腕、後ろに傾いた骨盤といった身振り手振りの特異性で構成され、「浮浪者」というキャラクターのコミカルな人物像を豊かにしている。 みすぼらしいがきちんとした服装、絶え間ない身だしなみ、幾何学的な歩き方と動きによって、彼のスクリーン上のキャラクターは操り人形のような質感を持つようになった。

チャップリンのサイレント映画は、通常、敵対的な世界で生き延びようとする不逞の男の努力を描いている。 貧困にあえぎ、ひどい扱いを受けることもしばしばだが、優しさと明るさを失わない。 1925年にチャップリンが言ったように、"リトル・フェローの要点は、彼がどんなに落ちぶれようとも、ジャッカルたちが彼を引き裂くことに成功しようとも、彼はまだ威厳のある人間であるということだ"。 不逞の輩は権力者に逆らい、"自分が得たものを与える "のであり、ロビンソンとルーヴィッシュは彼を恵まれない人々の代表、つまり "英雄的救世主と化した常人 "と見なした。 ハンスマイヤーは、チャップリンの映画のいくつかは、「ホームレスで孤独な不逞の輩が、楽観的に......夕日に向かって......旅を続けるために......歩いていく」ところで終わっていると指摘する。

悲劇が嘲笑の精神を刺激するのは逆説的である。嘲笑とは反抗の態度であり、自然の力に対して無力であることを笑わなければならない。

- チャーリー・チャップリン、彼の喜劇がしばしば悲劇的な状況を揶揄する理由を説明する。

ペーソスの注入はチャップリン作品のよく知られた側面であり、ラーチャーは「笑いと涙を誘う」という彼の評判に言及している。 ルーヴィッシュは「個人的な失敗、社会の厳しさ、経済的な災難、風雨」と指摘している。 チャップリンは、ドンナー党の運命に着想を得た『ゴールドラッシュ』(1925年)のように、映画を作る際に悲劇的な出来事を利用することもあった。 コンスタンス・B・栗山は、初期の喜劇には貪欲(『ゴールドラッシュ』)や喪失(『キッド』)といった深刻なテーマが根底にあることを明らかにしている。 チャップリンはまた、移民問題(『イミグラント』、1917年)、不法滞在(『キッド』、1921年)、麻薬使用(『イージー・ストリート』、1917年)など、物議を醸す問題にも触れている。 彼はしばしばこれらのテーマを皮肉たっぷりに取り上げ、苦悩を喜劇にした。

社会批評はチャップリン映画の初期の特徴であり、彼は負け犬を同情的に描き、貧しい人々の困難を浮き彫りにした。 その後、経済学に強い関心を持つようになり、自分の見解を公表する必要性を感じたチャップリンは、あからさまに政治的なメッセージを映画に盛り込むようになった。 モダン・タイムス』(1936年)は悲惨な状況に置かれた工場労働者を描き、『偉大なる独裁者』(1940年)はアドルフ・ヒトラーとベニート・ムッソリーニをパロディにし、最後はナショナリズムに反対する演説で締めくくる。

心理学者のジークムント・フロイトは、チャップリンは「いつも悲惨な青春時代の自分だけを演じている」と考えていた。 キッド』は孤児院に入れられたチャップリンの幼少期のトラウマを反映していると考えられ、『ライムライト』(1952年)の主要登場人物には彼の両親の生活の要素が含まれている。『ニューヨークの王様』はチャップリンがアメリカから疎外された経験を参照している。 また、『ニューヨークの王様』では、チャップリンがアメリカから疎外された体験が描かれている。チャップリンのセットの多く、特に街頭のシーンは、彼が育ったケニントンに酷似している。 スティーヴン・M・ワイズマンは、チャップリンが精神を病んだ母親との関係に問題を抱えていたことが、しばしば登場人物の女性や、彼女たちを救いたいと願うトランプに反映されていると論じている。

チャップリン映画の構成について、研究者のジェラルド・マストは、きっちりと統一されたストーリーがあるというよりは、同じテーマや設定で結びつけられたスケッチで構成されていると見ている。 視覚的にも、彼の映画はシンプルで経済的であり、まるで舞台のようにシーンが描かれている。 チャップリンは撮影中、"芸術的 "なイメージは考えなかった。 チャップリンは撮影時に "芸術的 "なイメージは考えなかった。 カメラは俳優を撮るためにある」。 チャップリンは自伝の中で、「シンプルが一番だ......華美な演出はアクションを遅らせ、退屈で不快だ......。 カメラは侵入すべきではない "と書いている。 このアプローチは、1940年代以降、"古臭い "という批判を招き、映画学者のドナルド・マカフリーは、チャップリンが映画というメディアを完全に理解していなかったことの表れだと見ている。 しかしカミンは、チャップリンの喜劇的才能は、「映画というメディアのために特別にシーンを構想し、演出する能力」がなければ、スクリーン上で面白さを維持するのに十分ではなかっただろうとコメントしている。

…

《》作曲

チャップリンは子供の頃から音楽への情熱を燃やし、独学でピアノ、ヴァイオリン、チェロを学んだ。 彼は映画の伴奏を重要なものと考え、『巴里の女』以降、この分野への関心を高めていった。 音響技術の出現に伴い、チャップリンは『街の灯』(1931年)で自作のオーケストラ・サウンドトラックを使い始めた。 1950年代後半から亡くなるまで、すべてのサイレント長編映画といくつかの短編映画の音楽を担当した。

チャップリンは訓練された音楽家ではなかったため、楽譜を読むことができず、楽譜を作る際にはデヴィッド・ラクシン、レイモンド・ラッシュ、エリック・ジェイムズといったプロの作曲家の助けが必要だった。 シティ・ライツ』のアルフレッド・ニューマンのように、レコーディング・プロセスを監督する音楽監督も雇われた。 彼の映画音楽の功績は、彼と仕事をした作曲家に与えられるべきだと主張する批評家もいるが、『モダン・タイムス』でチャップリンと仕事をしたラクシンは、チャップリンの創造的な立場と作曲過程への積極的な参加を強調した。 数ヶ月かかることもあるこのプロセスは、チャップリンが作曲家に自分の望みを正確に説明し、即興で作った曲をピアノで歌ったり演奏したりすることから始まる。 これらの曲は、作曲家とチャップリンの緊密な共同作業の中で、さらに発展させていった。 映画史家のジェフリー・バンスによれば、「彼は多様で複雑な楽器編成をアレンジするために仲間を頼ったとはいえ、音楽的要請は彼にあり、チャップリンの楽譜には彼の同意なしに置かれた音符はひとつもない」。

チャップリンの作曲は3つの人気曲を生み出した。 『Modern Times』(1936年)のために作曲され、後にジョン・ターナーとジェフリー・パーソンズが歌詞をつけた「Smile」は、1954年にナット・キング・コールのヒット曲となった。 ライムライト』のためにチャップリンは「Terry's Theme」を作曲し、これはジミー・ヤングによって「Eternally」(1952年)として広まった。 最後に、ペトゥラ・クラークが『香港から来た伯爵夫人』(1967年)のために演奏した「This Is My Song」は、全英および他のヨーロッパのチャートで1位を獲得した。 チャップリンはまた、この『ライムライト』のテーマが映画の再公開後の1973年にアカデミー賞作曲賞を受賞したため、彼の作曲作品に対して唯一のオスカーを受賞した。

…

〜

〜

〜〜

〜〜〜

〜〜〜

〜〜

〜

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?