「アフリカは団結しなければならない」: この男が米英に恐れられた理由

2024年 9月 21日 09:15

ホームアフリカ

「アフリカは団結しなければならない」: この男が米英に恐れられた理由

新植民地主義の本質を見抜いたクワメ・ンクルマの洞察力は時代を先取りし、今日でも通用する

サハラ以南のアフリカで初めて独立を果たした国の初代首相であるクワメ・ンクルマは、アフリカにおける自治のための闘いにおいて、傑出した人物であった。 汎アフリカ主義の熱烈な支持者であり、強大な政治理論家であった彼は、アフリカの20世紀の経験に「新植民地主義」という言葉を初めて適用したことで知られている。ヨーロッパ列強がさまざまな手段を用いて、かつてのアフリカ植民地を形式上は独立しても、事実上の従属状態に保つことを正しく予期していたのである。 しかし、1966年にCIAが支援したクーデターで失脚させられたことは、アフリカの解放に反対する勢力を思い起こさせるものでもある。

1909年9月21日、独立したガーナの舵を取ることになる彼は、ゴールドコースト(現ガーナ)の町ンクロフルでフランシス・ヌウィア・コフィ・ンゴロンマとして生まれた。 後にクワメ・ンクルマと改名。

ハーフ・アシニの町で基礎教育を受けた後、ガーナで教員養成課程に進んだ。 その後、ペンシルベニア州のリンカーン大学、後にロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスで研究を続けるために海外に渡った。 米国での滞在は人種差別と経済的制約に悩まされたが、同時に知的興奮の時期でもあった。

留学中、ンクルマはレーニン、マルクス、エンゲルスの著作に関心を持った。 このイデオロギー的なつながりは、1917年に出版されたレーニンの『帝国主義、資本主義の最終段階』を引用した1965年の著書『新植民地主義、帝国主義の最終段階』にも表れている。 この本は英国人を激怒させた。

哲学と政治理論に精通したンクルマは、自らを無宗派のキリスト教徒であり、マルクス主義社会主義者であると称した。 彼は社会主義が帝国主義からの解放の問題に対処していると考えていたが、正式な独立を達成したにもかかわらず、アフリカ人自身の利益のためにアフリカを発展させることを妨げる多くの経済構造が残っていると主張した。

一方、政治的に効果的に組織化するにはどうすればよいかという問題は未解決のままであったため、ンクルマは、アメリカのマーカス・ガーヴィーの「バック・トゥ・アフリカ」運動やロンドンの「西アフリカ学生連合」など、さまざまな政治的解放団体の活動に精通した。

エリートの台頭

第二次世界大戦が終結し、1945年に国連憲章に主権と自決の原則が採択されると、アフリカの人々は独立と自治を追求するようになった。 ガーナでは、教育を受けたエリートたちの間で大きなイデオロギー転換が起こった。 英国の植民地支配に不満を抱いていた彼らは、1947年に統一ゴールドコースト会議(UGCC)という政党を結成し、政治的代表権の拡大、経済的搾取の廃止、可能な限り短期間での独立を訴えた。

その目的を達成するために、党は大衆を鼓舞し、これらの理想を支持できる知識人を必要としていた。 傑出した指導者の一人がクワメ・ンクルマであった。彼はペンシルベニア大学にアフリカ学生学部を設立し、同大学のアフリカ学生組織をアメリカ・カナダアフリカ学生協会へと発展させる手助けをした。

その知性と政治活動の経験のおかげで、ンクルマは1947年にガーナに招かれ、UGCCの書記長となった。

刑務所からビッグ6へ

1948年にンクルマがガーナに到着した直後、英国植民地政府が第二次世界大戦で英国を代表して戦った元軍人への給与を渋ったこと、また高インフレとガーナ人の政治的代表が限られていたことから、ゴールドコーストで平和的抗議運動が起こった。 英国植民地政府は、請願書を提出するために植民地政府の所在地であるクリスチャンボルグ城まで平和的に行進していた3人の元軍人を射殺した。 彼らはまた、抗議を煽ったとして、ンクルマをUGCCの他の5人のメンバーとともに逮捕した。

獄中で、UGCCのメンバーはンクルマに対する敵意を強め、自分たちの不幸をンクルマになすりつけた。

しかし、この抗議運動により、英国植民地政府は立法改革を実施せざるを得なくなり、1951年にはガーナ人に広範な選挙代表権を与える憲法が採択された。 ンクルマと彼の党員たちは正当性を認められ、1948年4月に刑務所から釈放され、ビッグ6として知られるようになった。

選挙の勝利

独立闘争に関してUGCCがより保守的になっていたのに対し、ンクルマの急進主義は獄中での経験と相まって党とはそぐわなくなっていた。 その結果、彼はUGCCから離脱し、1949年に「今こそ自治を」をモットーに大会人民党(CPP)を結成した。

1950年1月、ンクルマはストライキとボイコットを含む非暴力の市民運動を組織し、即時の自治を要求した。 植民地側はこれを法の支配に対する脅威とみなし、1950年12月にンクルマを再び投獄した。 しかし、ンクルマの行動は、植民地独裁体制に辟易し、即時かつ急進的な自治への移行を望む大衆にアピールした。 この支持により、1951年2月の総選挙で、獄中にもかかわらずンクルマは議席を獲得した(当時の植民地政府は囚人の立候補を禁じていなかった)。 CPPはその後、植民地政府による政治的抑圧を利用して大衆にアピールするため、彼をアクラ中央選挙区に推薦した。 ンクルマは大差で当選した。

その後、植民地政府はンクルマを釈放せざるを得なくなり、彼は政府事業のリーダーとなった。 1952年には首相となり、1960年にはガーナ共和国の初代大統領に就任した。

"帝国主義の強さは不統一にある"

1957年3月6日、ンクルマ率いるガーナは独立を宣言。 しかしンクルマは、他のアフリカ諸国がまだ植民地支配下にあるのであれば、ガーナの独立は意味があるとは考えていなかった。 その結果、彼は独立記念日の演説でこう述べた: 「ガーナの独立は、アフリカ大陸の完全な解放に結びつかなければ意味がない」。

ンクルマのアフリカ統一のビジョンは、アメリカでは市民権運動家のW.E.B.デュボワとジャマイカ生まれの活動家マーカス・ガーベイが、イギリスでは1860年代にトリニダード出身のC.L.R.ジェームズとジョージ・パドモアが唱えた汎アフリカ主義の概念から発展したものだった。 汎アフリカ主義は、アフリカの文化的価値を促進し、それらの国のアフリカ系住民の団結を促進することを目的としていた。 そのため、この概念は目新しいものではなかったが、1958年にンクルマがガーナのアクラで初の国家間全アフリカ人民会議を開催し、アフリカそのものに普及させた。

当時、国連は植民地支配下にあった植民地を国家として認めず、世界的な重要な決定を下していた。 しかしンクルマは、アフリカの国家を解放するためには、まずアフリカの指導者を重要な意思決定者として認める必要があると考えた。 その顕著な例が、1958年にガーナで開催された会議に招待されたパトリス・ルムンバである。 2年後、ルムンバはこの会議に触発され、コンゴ民族運動を率いてベルギーからの独立を達成した。

ンクルマのアフリカ統一のコンセプトは、アフリカ大陸からひとつの国を作ることではなく、アフリカの国際競争力を高める特定の部門を統一することだった。 彼は、アフリカ社会主義と冷戦列強に対する中立性に基づき、アフリカ諸国の共通の外交政策、通貨、通貨圏、中央銀行、安全保障アーキテクチャを提唱した。 政治的には、この目標は、個々のアフリカ諸国がアフリカ以外の外国と安全保障協定を結ぶことで、アフリカ大陸が他国の代理戦争に巻き込まれることを恐れて生まれたものだった。

しかし、ンクルマのアフリカ社会主義という概念は、カルテルを通じて商業を独占し、ほとんどのアフリカ諸国で商品の価格を決定していた植民地支配に対する直接的な反応であった。 1963年、ンクルマは『Africa Must Unite(アフリカは団結しなければならない)』というタイトルの本を出版した。

ンクルマのビジョンは、タンザニアのジュリアス・ニエレレ、コンゴのルムンバ、その他のアフリカの指導者たちの関心を集めた。 その結果、同年、彼らは力を合わせ、アフリカ連合の前身であるアフリカ統一機構(OAU)を結成した。

「われわれは東も西も向いていない: 我々は前を向く」

しかし、ンクルマの反帝国主義的な思想は、当時は米国を含む植民地列強の脅威として認識されるようになった。 1964年、米国務省西アフリカ局長のマホニー・トリンブルは、ガーナに対する行動計画を提案した。

この計画は、民主的に選出されたンクルマを、米国の圧力と英国の援助によって打倒するというものだった。「米国の圧力が適切に適用されれば、連鎖反応を引き起こし、最終的にンクルマを失脚させることができる。 もし英国が我々と協調して行動するように仕向けることができれば、成功の可能性は大いに高まるだろう」。

米国はガーナに残るよう断固として努力すべきだ。 私たちの代表を自主的に撤退させれば、ガーナでもアフリカの他の場所でも、米国の敗北、共産主義者の勝利と解釈されるだろう。 また、アフリカの他の地域の共産主義者や左翼主義者たちが、ガーナで彼らがとっているのと同じ戦術をとることを助長するだろう。 ソ連圏は、われわれがガーナから撤退することを望んでおり、この目的の推進に積極的に取り組んでいる」。

米国はクーデターの理由として、ソ連がガーナと同盟を結ぶ可能性を挙げたが、ンクルマは一貫して非同盟政策をとっており、それは彼の有名な言葉に表れている: 「我々は東も西も向いていない:我々は東も西も向いていない」。

トリンブルはこう述べている: 「ンクルマは、アフリカ統一のための彼の計画にとって、米国が主要な障害であると確信している。 彼はまた、CIAを通じて、われわれが彼の失脚を画策していると確信している」。

一方、ンクルマは、アフリカ諸国が団結できなければ、帝国主義大国がアフリカ大陸でさらなる紛争を引き起こすと考えていた。 1958年の全アフリカ人民会議での演説で、彼はアフリカの指導者たちに「植民地大国にアフリカ人を分断させるな、アフリカ大陸の分断は彼らの利益なのだから」と呼びかけた。

『アフリカは団結しなければならない』(1963年)では、こう警告している:

「この大陸に対する彼らの継続的な覇権を確実にするために、彼らはあらゆる手段を使って、アフリカの膨大な数の人々の間で高まっている統一への意志を阻止し、崩壊させようとするだろう。 われわれの強さが統一政策にあるように、帝国主義者の強さは不統一にある」。

英国マスコミの秘密工作

1960年代、英国外務省の秘密宣伝部門である情報調査部(IRD)は、ンクルマを弱体化させるキャンペーンを行った。IRDが秘密裏に運営していた出版物『アフリカン・レビュー』に、ンクルマのアフリカ統一の努力をソ連の影響下でアフリカを支配しようとする試みであるとする記事を掲載したとされる。

これらの出版物は、しばしば架空の名前やグループのもとで作られたり、場合によっては報道されなかったりしたが、IRDとともに働いていた英国の外交官ジョン・ウレは、1966年の報告書でこのように記述している: 「IRDのアフリカ部門、編集部門、特殊作戦部門は、ンクルマのガーナに関するわれわれの扱いをめぐって、終始、非常に緊密な連携を保っていた。この扱いは、ンクルマが打倒され、より西欧志向の政府に取って代わられるような雰囲気づくりに貢献することを目的としていた」。

当時、ガーナ人の大半は農村部に住んでおり、ンクルマは彼らの間で絶大な人気を誇っていた。 しかし、この層はIRDのターゲットではなかった。 IRDは、中産階級と都市の知識人の間でンクルマの評判を落とそうとしていたのである。

"ガーナは誰にも謝罪する必要はない"

UGCCは、ンクルマが構想した統一に反対するイギリスが支持する分断を好む植民地イデオロギーをますます採用していた。 ガーナの外交政策に沿った統一を促進するため、同国の議会はンクルマの支持のもと、政府を不安定にしようとした者を訴追する予防拘禁法を可決した。 英国は、ンクルマに独裁者のレッテルを貼るため、この物議を醸す法案を利用した。

© Lincoln University via Getty Images

1963年、旧宗主国に融和的なアフリカ解放へのアプローチを好む指導者たちによって、ンクルマに対する反感が高まった。 フランスとの緊密な関係を維持したトーゴのシルバヌス・オリンピオやコートジボワールのフェリックス・ウフエ=ボワニーなどがその代表例である。 この対立は、フフエ=ボワニーに対する陰謀の告発や、それに続くオリンピオの殺害にまで発展した。 植民地主義者たちは、オリンピオがフランスの植民地軍に所属していた自軍のメンバーによって暗殺されたにもかかわらず、これらの出来事についてすぐにンクルマを非難した。

ンクルマは一連の非難に堂々と反論した:

「コンゴのニャースランドやアフリカの植民地地域で最近起こった騒乱を、全アフリカ人民会議での審議が直接の原因だとする人々が大勢いる。 そのような人々は、ガーナがアフリカにおけるすべての反帝国主義、反植民地主義勢力、そして独立を求める政治的扇動の中心地となったと信じている。 我々としては、これらの非難はアフリカの自由の敵がガーナに払うことのできる最大の賛辞であり、ガーナは誰に対しても謝罪する必要はなく、弁解する必要もないと言う」。

クーデターと遺産

一方、ンクルマには暗雲が立ち込めていた。ンクルマはすでに何度か暗殺未遂事件を乗り越えており、強権的な手段を用いたと非難されるようになっていた。

1966年2月、ンクルマはベトナム戦争交渉の仲介役としてハノイを訪問中、CIAの支援を受けた民族解放評議会(ガーナ軍を率いる軍事政権)の陰謀によって打倒された。 多くの情報筋が実証しているように、これはCIAが大いに援助したクーデターであった。

アンゴラ対策本部の元本部長で、後にCIAを批判したジョン・ストックウェルは、CIAのアクラ支局の諜報員が「クーデターが企てられる中、計画者と親密な接触を保っていた」と書いている。 その年の暮れ、シーモア・ハーシュは "第一級の情報筋"を引き合いに出し、ストックウェルの証言を支持した。

クーデターの2年後に書かれた『ガーナの暗い日々』という本の中で、亡命したンクルマはこう説明している: 我々の中にいる潜在的な "屁理屈屋 "や "裏切り者 "を発見し、賄賂や政治的権力の約束によって、自国の憲政を破壊するよう促すことが、CIAや他の類似組織の仕事のひとつだった」。

一方、クーデターの直後、ウレは冷ややかな、そして極めて重大な結論を記した報告書を書いた: 「今......われわれの努力は、ンクルマが共産主義になびいた教訓を他のアフリカ人たちが失わないようにすることに向けられている」。

クーデター後、ンクルマはモスクワ大学とソ連科学アカデミーから名誉博士号を授与され、ギニアに亡命した。 1972年4月27日、彼は癌のためこの世を去った。

ンクルマ大統領は長い間、人権侵害を行いながら国の経済運営をひどく誤った独裁者として、西側の情報源から軽蔑されていた。 しかし、ンクルマの後を継いだ親欧米派の民族解放評議会は、どちらの面でもはるかにひどいものだった。 さらに、民営化政策に乗り出し、ガーナ経済の大部分を欧米が支配するようになった。

彼の欠点が何であったにせよ、ンクルマは高くそびえ立つ先見者であり、アフリカの統一と自由へのたゆまぬ努力は完全に達成されることはなかったが、後世の光明であり続けた。 新植民地主義の本質を洞察した彼の洞察力は時代を先取りしており、今日でも十分に通用する。 彼がワシントンとロンドンで警戒の目を向けられていたことは、彼の影響力の大きさを物語っている。

西アフリカ移行期正義センター(WATJ)研究員、アフリカ開発のための国際パートナーシップ(IPAD)コーディネーター、マクスウェル・ボアマ・アモファ 記

スペイン語訳:

21 Sep, 2024 09:15

PortadaÁfrica

África debe unirse": Por qué Estados Unidos y Gran Bretaña temían a este hombre

La visión de Kwame Nkrumah sobre la verdadera naturaleza del neocolonialismo se adelantó a su tiempo y sigue siendo relevante hoy en día

Kwame Nkrumah, primer Primer Ministro del primer país del África subsahariana que obtuvo la independencia, fue una figura destacada en la lucha por el autogobierno en África. Ardiente defensor del panafricanismo y formidable teórico político, se le atribuye el mérito de ser el primero en aplicar el término "neocolonialismo" a la experiencia africana del siglo XX, anticipando acertadamente que las potencias europeas utilizarían diversos resortes para mantener a las antiguas colonias africanas en un estado de dependencia de facto aunque formalmente fueran independientes. Sin embargo, su derrocamiento en 1966, en un golpe de Estado respaldado por la CIA, también sirve como un duro recordatorio de las fuerzas alineadas contra la liberación africana.

El hombre que tomaría el timón de una Ghana independiente nació el 21 de septiembre de 1909 en Nkroful, una ciudad de la Costa de Oro (actual Ghana) con el nombre de Francis Nwia-Kofi Ngolonma. Más tarde cambió su nombre por el de Kwame Nkrumah.

Cursó estudios de magisterio en Ghana, tras completar su educación básica en la ciudad de Half Assini. Después se trasladó al extranjero para continuar sus estudios en la Universidad Lincoln de Pensilvania, y más tarde en la London School of Economics. Su estancia en Estados Unidos se vio empañada por el racismo y las limitaciones económicas, pero también fue una época de efervescencia intelectual.

Durante sus estudios, Nkrumah se interesó por los escritos de Lenin, Marx y Engels. Esta conexión ideológica es evidente en su libro de 1965 "El neocolonialismo, última etapa del imperialismo", una referencia a "El imperialismo, última etapa del capitalismo" de Lenin, publicado en 1917. Fue un libro que enfureció a los británicos.

RT

Vladimir Lenin, líder revolucionario comunista ruso, pronuncia un discurso ante los soldados de Vsevobuch en el primer aniversario de la fundación de las fuerzas armadas soviéticas, Plaza Roja, Moscú, 25 de mayo de 1919. Archivo Histórico Universal / Getty Images

Muy versado en filosofía y teoría política, Nkrumah se definía a sí mismo como cristiano aconfesional y marxista-socialista. Creía que el socialismo abordaba la cuestión de la liberación del imperialismo, pero sostenía que, a pesar de haber logrado la independencia formal, seguían vigentes muchas estructuras económicas que impedían el desarrollo de África en beneficio de los propios africanos.

Mientras tanto, la cuestión de cómo organizarse políticamente de forma eficaz seguía sin respuesta, por lo que Nkrumah se familiarizó con las actividades de diversas organizaciones de liberación política, como el movimiento Back to Africa de Marcus Garvey en Estados Unidos y la West African Students Union en Londres.

RT

Marcus Garvey desfilando. © George Rinhart / Corbis via Getty Images

El ascenso de las élites

El final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial y la adopción de los principios de soberanía y autodeterminación en la Carta de las Naciones Unidas en 1945 inspiraron a los africanos a buscar la independencia y el autogobierno. En Ghana se produjo un cambio ideológico significativo entre las élites educadas. Insatisfechas con la dominación colonial británica, formaron en 1947 un partido político conocido como la Convención de la Costa de Oro Unida (UGCC), que reclamaba una mayor representación política, el fin de la explotación económica y la independencia en el plazo más breve posible.

Para lograr sus objetivos, el partido necesitaba intelectuales que pudieran galvanizar a las masas y defender estos ideales. Un líder que destacó fue Kwame Nkrumah, que ayudó a crear el departamento de Estudiantes Africanos de la Universidad de Pensilvania y había contribuido a que la organización de estudiantes africanos de la universidad se convirtiera en la Asociación de Estudiantes Africanos de América y Canadá.

Gracias a su intelecto y experiencia en el activismo político, Nkrumah fue invitado a regresar a Ghana en 1947 para convertirse en secretario general de la UGCC.

De la cárcel a los Seis Grandes

Poco después de su llegada, en 1948, estallaron protestas pacíficas en la Costa de Oro por la reticencia del gobierno colonial británico a pagar a los ex militares que habían luchado en nombre de Gran Bretaña en la Segunda Guerra Mundial, y también por la elevada inflación y la escasa representación política de los ghaneses en los asuntos públicos. El gobierno colonial británico mató a tiros a tres ex militares que marchaban pacíficamente al castillo de Cristianborg, sede del gobierno colonial, para presentar su petición. También detuvieron a Nkrumah junto con otros cinco miembros de la UGCC por supuestamente alimentar la protesta.

Durante su estancia en prisión, los miembros de la UGCC se mostraron cada vez más hostiles hacia Nkrumah, culpándole de su desgracia.

RT

Kwame Nkrumah PC condujo a Ghana a la independencia de Gran Bretaña en 1957 y fue su primer primer ministro y presidente. © Universal History Archive / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Sin embargo, la protesta obligó al gobierno colonial británico a llevar a cabo reformas legislativas, medida que condujo a la adopción de una constitución en 1951 que proporcionaba una representación electoral más amplia a los ghaneses. Nkrumah y los miembros de su partido fueron reivindicados, salieron de prisión en abril de 1948 y pasaron a ser conocidos como los Seis Grandes.

Triunfo electoral

Mientras que la UGCC se había vuelto más conservadora con respecto a la lucha por la independencia, el radicalismo de Nkrumah, unido a su experiencia en prisión, le desubicó. En consecuencia, rompió con la UGCC y formó el Partido Popular de las Convenciones (CPP) en 1949 con el lema: "autogobierno ya".

Nkrumah organizó una operación civil no violenta con huelgas y boicots en enero de 1950 para exigir el autogobierno inmediato. Los colonizadores lo consideraron una amenaza para el estado de derecho y volvieron a encarcelar a Nkrumah en diciembre de 1950. Sin embargo, sus acciones atrajeron a las masas, que estaban hartas de la dictadura colonial y deseaban un cambio inmediato y radical hacia el autogobierno. Este apoyo le valió a Nkrumah un escaño en las elecciones generales de febrero de 1951, incluso estando en prisión (el gobierno colonial de la época no prohibía a los presos presentarse a las elecciones). El CPP le propuso entonces para la circunscripción de Accra Central, aprovechando la opresión política del gobierno colonial para atraer a las masas. Nkrumah ganó las elecciones por un amplio margen.

El gobierno colonial se vio entonces obligado a liberar a Nkrumah, permitiéndole convertirse en el líder de los negocios del gobierno. En 1952 se convirtió en Primer Ministro y en 1960 asumió el cargo de primer Presidente de la República de Ghana.

"La fuerza del imperialismo reside en la desunión"

El 6 de marzo de 1957, Ghana, bajo el mandato de Nkrumah, declaró la independencia. Sin embargo, Nkrumah no estaba convencido de que la independencia de Ghana fuera relevante si otros países africanos seguían bajo dominio colonial. En consecuencia, declaró en su discurso del Día de la Independencia: "La independencia de Ghana carece de sentido si no va unida a la liberación total del continente africano".

La visión de Nkrumah de la unidad africana había evolucionado a partir de un concepto de panafricanismo defendido por el activista de los derechos civiles W.E.B. Du Bois y el activista nacido en Jamaica Marcus Garvey en Estados Unidos, y por C.L.R. James y George Padmore, ambos de Trinidad, en Gran Bretaña en la década de 1860. El panafricanismo pretendía promover los valores culturales africanos y fomentar la unidad entre los afrodescendientes de esos países. Por tanto, el concepto no era nuevo, pero Nkrumah lo popularizó en la propia África en 1958, cuando organizó la primera conferencia interestatal de todos los pueblos africanos en Accra (Ghana).

RT

Delegaciones de 30 naciones africanas independientes se reúnen en la conferencia de Jefes de Estado, inaugurada el 22 de mayo y culminada el 25 de mayo con la firma de una carta para una nueva organización de unidad africana que sustituya a los bloques rivales del continente. Getty Images

En aquella época, la ONU no reconocía como Estados a las colonias bajo dominio colonial a la hora de tomar decisiones globales importantes. Nkrumah, sin embargo, creía que para liberar a los Estados africanos primero era necesario reconocer a los líderes africanos como importantes responsables de la toma de decisiones. Un ejemplo notable fue Patrice Lumumba, invitado a la conferencia de 1958 en Ghana. Dos años más tarde, Lumumba, inspirado por la conferencia, dirigió el Movimiento Nacional Congoleño para lograr la independencia de Bélgica.

El concepto de unidad africana de Nkrumah no consistía en crear un único país a partir del continente africano, sino en unificar ciertos sectores que pudieran hacer a África competitiva a escala mundial. Defendió una política exterior común, una moneda, una zona monetaria, un banco central y una arquitectura de seguridad para los Estados africanos basada en el socialismo africano y la neutralidad frente a las potencias de la Guerra Fría. Desde el punto de vista político, este objetivo nació del temor a que los Estados africanos por separado pudieran firmar acuerdos de seguridad con países extranjeros ajenos a África, con lo que el continente se hundiría en guerras por delegación en nombre de otros.

Sin embargo, su concepto de socialismo africano era una respuesta directa al funcionamiento de las potencias coloniales que, a través de cárteles, dictaban los precios de los bienes en la mayoría de los estados africanos debido a los monopolios que ejercían en el comercio. En 1963, Nkrumah publicó un libro titulado "África debe unirse", que condensaba su visión de un África unificada.

La visión de Nkrumah atrajo el interés de Julius Nyerere, de Tanzania, Lumumba, del Congo, y otros líderes africanos. Ese mismo año, unieron sus fuerzas para formar la Organización para la Unidad Africana (OUA), precursora de la Unión Africana.

"No miramos ni al Este ni al Oeste: Miramos hacia delante"

Sin embargo, las ideas antiimperialistas de Nkrumah eran percibidas cada vez más como una amenaza por las potencias coloniales, incluido, por aquel entonces, Estados Unidos. En 1964, Mahoney Trimble, director de la oficina de Asuntos de África Occidental del Departamento de Estado estadounidense, propuso un programa de acción para Ghana.El plan consistía en derrocar a Nkrumah, elegido democráticamente, mediante la presión de Estados Unidos con la ayuda de Gran Bretaña: "La presión de Estados Unidos, si se aplica adecuadamente, podría inducir una reacción en cadena que llevaría finalmente a la caída de Nkrumah. Las posibilidades de éxito aumentarían enormemente si se pudiera inducir a los británicos a actuar de común acuerdo con nosotros".

En Estados Unidos existía un gran temor a los "elementos de izquierda" en Ghana: "Estados Unidos debería hacer un esfuerzo decidido por permanecer en Ghana. La retirada voluntaria de nuestra representación sería interpretada tanto allí como en cualquier otra parte de África como una derrota para EE.UU. y una victoria para los comunistas. También animaría a los comunistas y a los elementos izquierdistas de otras partes de África a adoptar las mismas tácticas que han estado siguiendo en Ghana. El bloque soviético desea que abandonemos Ghana y está activamente comprometido en promover este fin".

EE.UU. citó las posibilidades de que la Unión Soviética se alineara con Ghana como motivo del golpe propuesto, a pesar de que Nkrumah seguía sistemáticamente una política de no alineamiento, expresada en su famoso dicho: "No miramos ni al Este ni al Oeste: miramos hacia delante".

Trimble declaró: "Nkrumah está convencido de que Estados Unidos es el principal obstáculo para su programa de unidad africana. También está convencido de que, a través de la CIA, estamos intentando urdir su caída".

RT

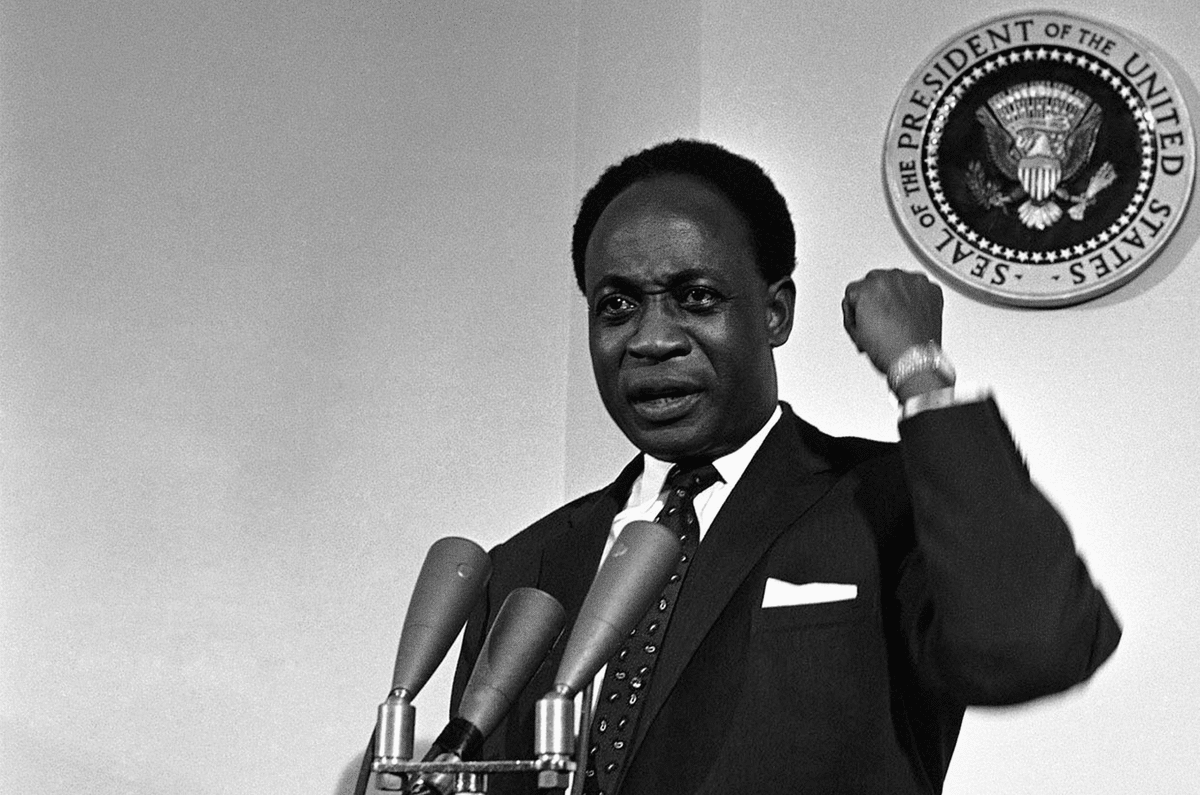

El presidente Kwame Nkrumah de Ghana se dirige a la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas, Nueva York, Nueva York, 23 de septiembre de 1960. Archivos Underwood / Getty Images

Nkrumah, por su parte, creía que si los Estados africanos no se unían, las potencias imperialistas instigarían nuevos conflictos en el continente. En un discurso pronunciado en 1958 durante el Congreso Panafricano de los Pueblos, pidió a los líderes africanos que "no dejaran que las potencias coloniales dividieran a los africanos, porque la división del continente africano es su ganancia".

En "África debe unirse" (1963), advirtió:

"Para asegurar su continua hegemonía sobre este continente, utilizarán todas y cada una de las artimañas para detener y desbaratar la creciente voluntad de unidad entre las vastas masas de la población africana. Así como nuestra fuerza reside en una política unificada, la fuerza de los imperialistas reside en la desunión".

Operaciones encubiertas de la prensa británica

En la década de 1960, el Departamento de Investigación de la Información (IRD), una unidad de propaganda encubierta del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores del Reino Unido, llevó a cabo una campaña para debilitar a Nkrumah, incluyendo la supuesta publicación de varios artículos en la African Review, una publicación dirigida en secreto por el IRD, en los que se describían los esfuerzos de Nkrumah por la unidad de África como un intento de gobernar África bajo influencia soviética.

Estas publicaciones se hacían a menudo bajo nombres y grupos ficticios o, en algunos casos, no eran atribuibles, como describió en un informe de 1966 el diplomático británico John Ure, que trabajaba con el IRD: "Las secciones africana, editorial y de operaciones especiales del IRD han trabajado, en todo momento, en muy estrecha relación sobre nuestro tratamiento de la Ghana de Nkrumah; este tratamiento tenía como objetivo contribuir a la creación de una atmósfera en la que Nkrumah pudiera ser derrocado y sustituido por un gobierno más orientado hacia Occidente".

La mayoría de los ghaneses vivían entonces en zonas rurales, y Nkrumah gozaba de gran popularidad entre ellos. Sin embargo, esta cohorte no era el objetivo de los esfuerzos del IRD. Buscaba empañar a Nkrumah entre la clase media y los intelectuales urbanos.

"Ghana no tiene disculpas que ofrecer a nadie"

La UGCC había adoptado cada vez más la ideología colonial favorable a las divisiones defendida por Gran Bretaña, que se oponía a la unidad prevista por Nkrumah. Para promover la unidad en consonancia con la política exterior de Ghana, el parlamento del país aprobó, con el apoyo de Nkrumah, la Ley de Detención Preventiva para perseguir a quienes intentaran desestabilizar al gobierno. Los británicos aprovecharon esta polémica ley para tachar a Nkrumah de dictador.

RT

Retrato de Kwame Nkrumah, teórico político y revolucionario. © Lincoln University via Getty Images

En 1963, surgió un antagonismo contra Nkrumah por parte de líderes que preferían un enfoque de la liberación africana más conciliador con las antiguas potencias coloniales. Ejemplos notables eran Sylvanus Olympio, de Togo, y Felix Houphouet-Boigny, de Costa de Marfil, que mantenían lazos más estrechos con Francia. Este antagonismo llegó a incluir acusaciones de complot contra Houphouet-Boigny y el posterior asesinato de Olympio. Los colonialistas se apresuraron a culpar a Nkrumah de estos sucesos, aunque Olympio fue asesinado por miembros de su propio ejército, muchos de los cuales habían servido en las fuerzas coloniales francesas.

Nkrumah respondió a la serie de acusaciones sin disculparse:

"Hay mucha gente que atribuye los recientes disturbios de Nyaasland en el Congo y en territorios coloniales de África directamente a las deliberaciones que tuvieron lugar en la Conferencia Panafricana de los Pueblos. Tales personas creen que Ghana se ha convertido en un punto focal para todas las fuerzas antiimperialistas, anticoloniales y agitaciones políticas por la Independencia en África. Por nuestra parte, decimos que estas acusaciones son los mayores homenajes que los enemigos de la libertad de África podrían rendir a Ghana y que Ghana no tiene disculpas que ofrecer a nadie ni excusas que poner."

Golpe y legado

Mientras tanto, se cernían negros nubarrones sobre Nkrumah, que ya había sobrevivido a varios intentos de asesinato y al que se acusaba cada vez más de emplear métodos de mano dura.

Mientras visitaba Hanoi en febrero de 1966, donde mediaba en las conversaciones sobre la guerra de Vietnam, Nkrumah fue derrocado en un complot dirigido por el Consejo de Liberación Nacional, respaldado por la CIA, una junta militar encabezada por elementos del ejército ghanés, muchos de los cuales habían sido educados en academias militares británicas. Fue un golpe muy ayudado por la CIA, como han demostrado numerosas fuentes.

John Stockwell, antiguo jefe de la Task Force de Angola que más tarde criticó a la CIA, escribió que los agentes de la estación de la agencia en Accra "mantuvieron un contacto íntimo con los conspiradores mientras se urdía el golpe". Ese mismo año, Seymour Hersh apoyó el relato de Stockwell, citando "fuentes de inteligencia de primera mano".

En un libro titulado "Días oscuros en Ghana", escrito dos años después del golpe, un Nkrumah exiliado explicaba que: "Ha sido una de las tareas de la CIA y de otras organizaciones similares descubrir... quislings y traidores potenciales entre nosotros, y animarles, mediante el soborno y la promesa de poder político, a destruir el gobierno constitucional de sus países."

Mientras tanto, poco después del golpe Ure escribió un informe con una conclusión escalofriante y bastante reveladora: "Ahora ... nuestros esfuerzos se dirigen a asegurar que la lección del coqueteo de Nkrumah con el comunismo no se pierda en otros africanos".

Tras el golpe, Nkrumah, que acabó recibiendo un doctorado honoris causa de la Universidad Estatal de Moscú y de la Academia de Ciencias de la URSS, se exilió en Guinea. Acabaría muriendo de cáncer el 27 de abril de 1972.

RT

El presidente y primer ministro de Ghana, Dr.Kwame Nkrumah, y el presidente del Consejo Supremo de la URSS, Leonid Brézhnev, pasando revista a la guardia de honor antes de la salida del presidente ghanés de la URSS, aeropuerto de Vnukovo. © Sputnik / Dmitriy Kozlov

Nkrumah había sido desprestigiado durante mucho tiempo por las fuentes occidentales como un dictador que gestionó muy mal la economía de su país al tiempo que cometía abusos contra los derechos humanos. Sin embargo, el Consejo Nacional de Liberación prooccidental que le sucedió fue mucho peor en ambos frentes. Además, emprendió una política de privatización que facilitó el retorno del control occidental sobre gran parte de la economía de Ghana.

Fueran cuales fueran sus defectos, Nkrumah fue un visionario imponente, cuyos incansables esfuerzos en pro de la unidad y la libertad africanas nunca se lograron plenamente, pero han seguido siendo un faro de luz para las generaciones posteriores. Su visión de la verdadera naturaleza del neocolonialismo se adelantó a su tiempo y sigue siendo relevante hoy en día. El hecho de que en Washington y Londres se le mirara con tanta cautela demuestra el alcance de su influencia.

Por Maxwell Boamah Amofa, investigador del Centro de Justicia Transicional de África Occidental (WATJ) y Coordinador de la Asociación Internacional para el Desarrollo de África (IPAD).

原文:

21 Sep, 2024 09:15

HomeAfrica

‘Africa must unite’: Why this man was feared by the US and Britain

Kwame Nkrumah’s insight into the true nature of neo-colonialism was ahead of his time and is still relevant today

Kwame Nkrumah, the first prime minister of the first sub-Saharan African country to gain independence, was a towering figure in the struggle for self-governance in Africa. An ardent proponent of pan-Africanism and a formidable political theorist, he is credited with being the first to apply the term ‘neo-colonialism’ to Africa’s 20th century experience, correctly anticipating that European powers would use various levers to keep former African colonies in a state of de-facto dependency even if formally independent. His ouster in a 1966 CIA-backed coup, however, also serves as a stark reminder of the forces aligned against African liberation.

The man who would take the helm of an independent Ghana was born on September 21, 1909 in Nkroful, a town in the Gold Coast (now Ghana) as Francis Nwia-Kofi Ngolonma. He later changed his name to Kwame Nkrumah.

He pursued teacher training in Ghana, after completing his basic education in the town of Half Assini. He then moved abroad to continue his studies at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, and later at the London School of Economics. His stay in the US was marred by racism and financial constraints – and yet was also a time of intellectual ferment.

During his studies, Nkrumah took an interest in the writings of Lenin, Marx, and Engels. This ideological connection is evident in his book from 1965 ‘Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism’, a reference to Lenin’s ‘Imperialism, the Last Stage of Capitalism’ published in 1917. It was a book that infuriated the British.

RT

Russian communist revolutionary leader, Vladimir Lenin, giving a speech to Vsevobuch servicemen on the first anniversary of the foundation of the Soviet armed forces, Red Square, Moscow, 25th May 1919. © Universal History Archive / Getty Images

Well-versed in philosophy and political theory, Nkrumah referred to himself as a non-denominational Christian and a Marxist-socialist. He believed socialism addressed the question of liberation from imperialism but argued that, despite achieving formal independence, many economic structures remained in place that prevented Africa from being developed for the benefit of Africans themselves.

Meanwhile, the question of how to effectively organize politically remained unanswered, so Nkrumah acquainted himself with the activities of various political liberation organizations, such as Marcus Garvey’s Back to Africa movement in the US and the West African Students Union in London.

RT

Marcus Garvey riding in parade. © George Rinhart / Corbis via Getty Images

The rise of the elites

The end of World War II and the adoption of the principles of sovereignty and self-determination in the United Nations charter in 1945 inspired Africans to pursue independence and self-rule. In Ghana, there was a significant ideological shift among the educated elites. Dissatisfied with British colonial rule, they formed a political party known as the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) in 1947, which called for greater political representation, an end to economic exploitation, and independence within the shortest possible time.

To achieve its aims, the party needed intellectuals who could galvanize the masses and champion these ideals. One leader who stood out was Kwame Nkrumah, who helped establish the African Students department at the University of Pennsylvania and had helped build the university’s African students organization into the African Students Association of America and Canada.

Thanks to his intellect and experience in political activism, Nkrumah was invited back to Ghana in 1947 to become the general secretary of the UGCC.

From prison to the Big Six

Shortly after his arrival in 1948, peaceful protests broke out in the Gold Coast following the British colonial government’s reluctance to pay ex-servicemen who had fought on behalf of Britain in World War II, and also due to high inflation and limited political representation of Ghanaians in public affairs. The British colonial government shot to death three ex-servicemen who were peacefully marching to the Cristianborg castle, the seat of the colonial government, to present their petition. They also arrested Nkrumah together with five other members of the UGCC for allegedly fueling the protest.

While in prison, the members of the UGCC grew increasingly hostile toward Nkrumah, blaming him for their misfortune.

RT

Kwame Nkrumah PC led Ghana to independence from Britain in 1957 and served as its first prime minister and president. © Universal History Archive / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

However, the protest forced the British colonial government to conduct legislative reforms, a move that led to the adoption of a constitution in 1951 that provided broader electoral representation for Ghanaians. Nkrumah and his party members were vindicated, released from prison in April 1948, and became known as the Big Six.

Election triumph

Whereas the UGCC had become more conservative regarding the independence struggle, Nkrumah’s radicalism coupled with his prison experience put him out of step with the party. Consequently, he broke away from the UGCC and formed the Conventions People’s Party (CPP) in 1949 with the motto: “self-government now.”

Nkrumah organized a non-violent civil operation involving strikes and boycotts in January 1950 to demand immediate self-rule. The colonizers depicted this as a threat to the rule of law and imprisoned Nkrumah again in December 1950. However, his actions appealed to the masses, who were fed up with the colonial dictatorship and desired an immediate and radical shift to self-rule. This support won Nkrumah a seat in the general elections in February 1951 even while he was in prison (the colonial government at the time did not bar prisoners from running for office). The CPP then nominated him for the Accra Central constituency, capitalizing on the political oppression by the colonial government to appeal to the masses. Nkrumah won the election by a wide margin.

The colonial government was then forced to release Nkrumah, allowing him to become the leader of government business. In 1952, he became the prime minister and in 1960 he took over as the first president of the Republic of Ghana.

“The strength of the imperialist lies in disunity”

On March 6, 1957, Ghana under Nkrumah declared independence. However, Nkrumah was not convinced that Ghanaian independence was relevant if other African countries were still under colonial rule. Consequently, he stated in his Independence Day speech: “The independence of Ghana is meaningless unless it’s linked to the total liberation of the African continent.”

Nkrumah’s vision of African unity had evolved from a concept of Pan-Africanism championed by civil right activist W.E.B. Du Bois and Jamaica-born activist Marcus Garvey in the US, and by C.L.R. James and George Padmore, both from Trinidad, in Britain in the 1860s. Pan-Africanism was aimed at promoting African cultural values and fostering unity among people of African descent in those countries. Therefore, the concept wasn’t new, but Nkrumah popularized it in Africa itself in 1958 when he organized the first inter-state All-African People’s conference in Accra, Ghana.

RT

Delegations from 30 independent African nations get together at heads of state conference, which opened May 22, was climaxed May 25 by the signing of a charter for a new organization of African unity to replace rival blocs with the continent. © Getty Images

At the time, the UN did not recognize colonies under colonial rule as states in making important global decisions. Nkrumah, however, believed that liberating African states first required recognizing African leaders as important decision makers. A notable example was Patrice Lumumba who was invited to the 1958 conference in Ghana. Two years later, Lumumba, inspired by the conference, led the Congolese National Movement to achieve independence from Belgium.

Nkrumah’s concept of African unity was not to create a single country out of the African continent but to unify certain sectors that could make Africa competitive globally. He championed a common foreign policy, currency, monetary zone, central bank, and security architecture for African states based on African socialism and neutrality toward the Cold War powers. Politically, this goal was born out of fear that individual African states could enter into security agreements with foreign countries outside Africa, and thus the continent would sink into proxy wars on behalf of others.

However, his concept of African socialism was a direct response to the operation of the colonial powers which, through cartels, dictated prices for goods in most African states due to the monopolies they exercised in commerce. In 1963, Nkrumah published a book titled ‘Africa Must Unite’, which encapsulated his vision for a unified Africa.

Nkrumah’s vision attracted the interest of Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Lumumba of Congo, and other African leaders. Consequently, in the same year, they combined forces to form the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the forerunner of the African Union.

“We face neither East nor West: We face forward”

However, Nkrumah’s anti-imperialist ideas were increasingly perceived as a threat by the colonial powers, including, by that time, the US. In 1964, Mahoney Trimble, the US State Department director for the office of West African Affairs, proposed an action program for Ghana.

The plan entailed overthrowing the democratically elected Nkrumah through US pressure with assistance from Britain: “U.S. pressure, if appropriately applied, could induce a chain reaction eventually leading to Nkrumah’s downfall. Chances of success would be greatly enhanced if the British could be induced to act in concert with us.”

There was a great fear in the US of ‘leftist elements’ in Ghana: “The U.S. should make a determined effort to remain in Ghana. Voluntary withdrawal of our representation would be interpreted both there and elsewhere in Africa as a defeat for the U.S. and a victory for the Communists. It also would encourage the Communists and leftist elements in other parts of Africa to adopt the same tactics they have been following in Ghana. The Soviet bloc desires us to leave Ghana and is actively engaged in promoting this end.”

The US cited the chances of the Soviet Union aligning with Ghana as a reason for the proposed coup, even though Nkrumah consistently pursed a policy of non-alignment, which was expressed in his famous saying: “We face neither East nor West: we face forward.”

Trimble stated: “Nkrumah is convinced that the U.S. is the principal obstacle to his program for African unity. He is also convinced that through the CIA we are seeking to engineer his downfall.”

RT

President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana addresses the General Assembly of the United Nations, New York, New York, September 23, 1960. © Underwood Archives / Getty Images

Nkrumah, meanwhile, believed that if African states failed to unite the imperialist powers would instigate further conflicts on the continent. In a 1958 speech during the All-African People’s Congress, he called on African leaders to “not let the colonial powers divide Africans, for the division of the African continent is their gain.”

In ‘Africa Must Unite’ (1963), he warned:

“To ensure their continuous hegemony over this continent, they will use every and any device to halt and disrupt the growing will among the vast masses of African population for unity. Just as our strength lies in a unified policy, the strength of the imperialist lies in disunity.”

Covert operations of the British press

In the 1960s, the Information Research Department (IRD), a covert propaganda unit of the UK’s Foreign Office, carried out a campaign to undermine Nkrumah, including allegedly publishing several articles in the African Review, a publication secretly run by the IRD, in which they described Nkrumah’s Africa unity efforts as an attempt to rule Africa under Soviet influence.

These publications were often made under fictitious names and groups or in some cases were unattributable, which British diplomat John Ure, who worked with the IRD, described in a report in 1966: “The African, Editorial and Special Operations Sections of IRD have, throughout, worked in very close liaison over our treatment of Nkrumah’s Ghana; this treatment aimed at contributing to the creation of an atmosphere in which Nkrumah could be overthrown and replaced with a more Western-Oriented government.”

Most Ghanaians lived in rural areas at the time, and Nkrumah enjoyed significant popularity among them. However, this cohort was not the target of the IRD’s efforts. It was seeking to tarnish Nkrumah among the middle class and the urban intellectuals.

“Ghana has no apologies to render to anybody”

The UGCC had increasingly adopted colonial ideology favoring divisions championed by Britain, which opposed the unity envisaged by Nkrumah. To promote unity in line with Ghana’s foreign policy, the country’s parliament passed with Nkrumah’s support the Preventive Detention Act to prosecute those who attempted to destabilize the government. The British capitalized on this controversial piece of legislation to label Nkrumah a dictator.

RT

Portrait of Kwame Nkrumah, political theorist and revolutionary. © Lincoln University via Getty Images

In 1963, antagonism rose against Nkrumah by leaders who preferred an approach towards African liberation that was more conciliatory toward the former colonial powers. Notable examples were Sylvanus Olympio of Togo and Felix Houphouet-Boigny of Ivory Coast, who maintained closer ties with France. This antagonism grew to include accusations of a plot against Houphouet-Boigny and subsequent murder of Olympio. The colonialists were quick to blame Nkrumah for these occurrences, though Olympio was assassinated by members of his own army, many of whom had served in the French colonial force.

Nkrumah responded to the series of accusations unapologetically:

“There are many people who attribute the recent disturbances in Nyaasland in the Congo and in colonial territories of Africa directly to the deliberations which took place at the All-African People’s Conference. Such people believe Ghana has become a focal point for all of the anti-imperialist, anti-colonial forces and political agitations for Independence in Africa. On our part, we say these accusations are the greatest tributes that the enemies of Africa’s freedom could pay to Ghana and Ghana has no apologies to render to anybody nor has any excuses to make.”

Coup and legacy

Meanwhile, dark clouds were gathering over Nkrumah, who had already survived several assassination attempts and was being increasingly accused of employed strong-arm methods.

While visiting Hanoi in February 1966, where he was mediating Vietnam War talks, Nkrumah was overthrown in a plot led by the CIA-backed National Liberation Council, a military junta headed up by elements of the Ghanaian military, many of whom had been educated at British military academies. It was a coup very much aided by the CIA, as numerous sources have demonstrated.

John Stockwell, former chief of the Angola Task Force who later criticized the CIA, wrote that agents at the agency’s Accra station “maintained intimate contact with the plotters as a coup was hatched.” Later that same year, Seymour Hersh supported Stockwell’s account, citing “first hand intelligence sources.”

In a book called ‘Dark Days in Ghana’ written two years after the coup, an exiled Nkrumah explained that: “It has been one of the tasks of the CIA and other similar organizations to discover… potential quislings and traitors in our midst, and to encourage them, by bribery and the promise of political power, to destroy the constitutional government of their countries.”

Meanwhile, shortly after the coup Ure wrote a report with a chilling and quite telling conclusion: “Now … our efforts are being directed at ensuring that the lesson of Nkrumah’s flirtation with Communism is not lost on other Africans.”

After the coup Nkrumah, who ended up receiving an honorary doctorate from the Moscow State University and the USSR Academy of Sciences, went into exile in Guinea. He would end up dying of cancer on April 27, 1972.

RT

Ghanaian President and Prime Minister Dr.Kwame Nkrumah and USSR Supreme Council President Leonid Brezhnev reviewing guards of honor before the Ghanaian president's departure from the USSR, Vnukovo airport. © Sputnik / Dmitriy Kozlov

Nkrumah had long been disparaged in Western sources as a dictator who badly mismanaged his country’s economy while engaging in human rights abuses. And yet the pro-Western National Liberation Council that succeeded him was far worse on both fronts. Furthermore, it embarked on a policy of privatization that facilitated the return of Western control over much of Ghana’s economy.

Whatever his shortcomings may have been, Nkrumah was a towering visionary, whose tireless efforts at African unity and freedom were never fully achieved, but have remained a beacon of light for subsequent generations. His insight into the true nature of neo-colonialism was ahead of his time and is still relevant today. That he was looked upon so warily in Washington and London is a testament to the scope of his influence.

By Maxwell Boamah Amofa, research officer at the West Africa Transitional Justice Center (WATJ) and Coordinator for International Partnerships for African Development (IPAD)

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?