mCOVID-19 vaccine efficacy and effectiveness—the elephant(not) in the room(メモ)

Lancet Microbe 2021

Published Online

April 20, 2021

https://doi.org/10.1016/

S2666-5247(21)00069-0

Approximately 96 COVID-19 vaccines are at various

stages of clinical development.1

At present, we have the

interim results of four studies published in scientific

journals (on the Pfizer–BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA

vaccine,2

the Moderna–US National Institutes of

Health [NIH] mRNA-1273 vaccine,3

the AstraZeneca–

Oxford ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccine,4

and the Gamaleya

GamCovidVac [Sputnik V] vaccine)5

and three studies

through the US Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) briefing documents (on the Pfizer–BioNTech,6

Moderna–NIH,7

and Johnson & Johnson [J&J] Ad26.

COV2.S vaccines).8

Furthermore, excerpts of these results

have been widely communicated and debated through

press releases and media, sometimes in misleading

ways.9

Although attention has focused on vaccine

efficacy and comparing the reduction of the number

of symptomatic cases, fully understanding the efficacy

and effectiveness of vaccines is less straightforward

than it might seem. Depending on how the effect size

is expressed, a quite different picture might emerge

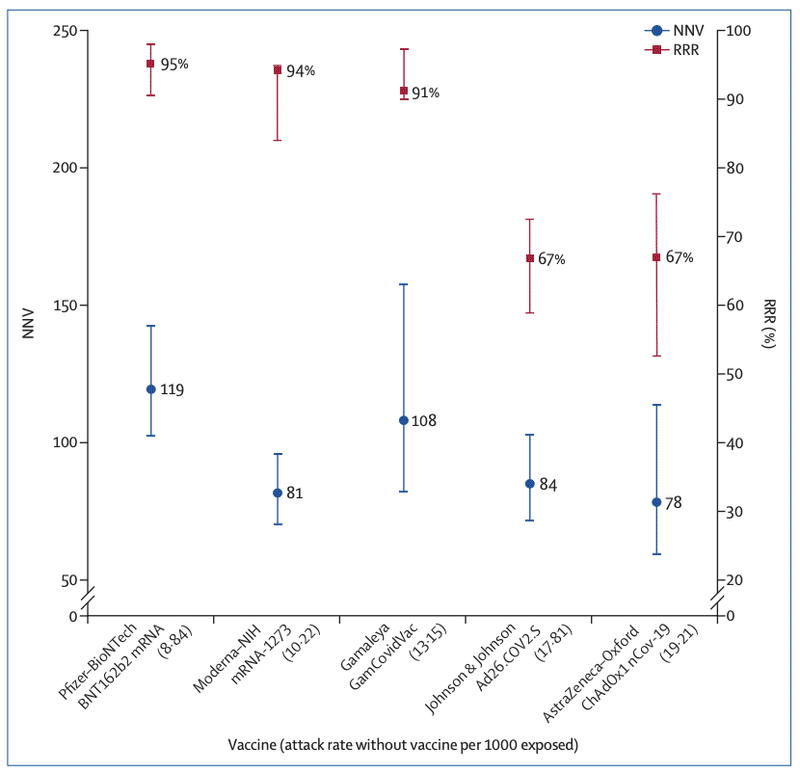

(figure; appendix).

Vaccine efficacy is generally reported as a relative risk

reduction (RRR). It uses the relative risk (RR)—ie, the

ratio of attack rates with and without a vaccine—which

is expressed as 1–RR. Ranking by reported efficacy gives

relative risk reductions of 95% for the Pfizer–BioNTech,

94% for the Moderna–NIH, 90% for the Gamaleya,

67% for the J&J, and 67% for the AstraZeneca–Oxford

vaccines. However, RRR should be seen against the

background risk of being infected and becoming ill

with COVID-19, which varies between populations and

over time. Although the RRR considers only participants

who could benefit from the vaccine, the absolute risk

reduction (ARR), which is the difference between attack

rates with and without a vaccine, considers the whole

population. ARRs tend to be ignored because they give

a much less impressive effect size than RRRs: 1·3% for

the AstraZeneca–Oxford, 1·2% for the Moderna–NIH,

1·2% for the J&J, 0·93% for the Gamaleya, and 0·84% for

the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccines.

ARR is also used to derive an estimate of vaccine

effectiveness, which is the number needed to vaccinate

(NNV) to prevent one more case of COVID-19 as 1/ARR.

NNVs bring a different perspective: 76 for the Moderna–

NIH, 78 for the AstraZeneca–Oxford, 80 for the Gamaleya,

84 for the J&J, and 117 for the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccines.

The explanation lies in the combination of vaccine

efficacy and different background risks of COVID-19

across studies: 0·9% for the Pfizer–BioNTech, 1% for the

Gamaleya, 1·4% for the Moderna–NIH, 1·8% for the J&J,

and 1·9% for the AstraZeneca–Oxford vaccines.

ARR (and NNV) are sensitive to background risk—

the higher the risk, the higher the effectiveness—as

exemplified by the analyses of the J&J’s vaccine on

centrally confirmed cases compared with all cases:8

both

the numerator and denominator change, RRR does

not change (66–67%), but the one-third increase in

attack rates in the unvaccinated group (from 1·8% to

2·4%) translates in a one-fourth decrease in NNV (from

84 to 64).

See Online for appendix

Figure: RRR and NNV with 95% CI ranked by attack rate in the unvaccinated (placebo) group for five

COVID-19 vaccines

The lower the NNV and the higher the RRR, the better the vaccine efficacy. Details are in the appendix (p 3).

RRR=relative risk reduction. NNV=numbers needed to vaccinate. NIH=US National Institutes of Health

There are many lessons to learn from the way studies

are conducted and results are presented. With the use

of only RRRs, and omitting ARRs, reporting bias is

introduced, which affects the interpretation of vaccine

efficacy.10 When communicating about vaccine efficacy,

especially for public health decisions such as choosing

the type of vaccines to purchase and deploy, having a

full picture of what the data actually show is important,

and ensuring comparisons are based on the combined

evidence that puts vaccine trial results in context and not

just looking at one summary measure, is also important.

Such decisions should be properly informed by detailed

understanding of study results, requiring access to full

datasets and independent scrutiny and analyses.

Unfortunately, comparing vaccines on the basis of

currently available trial (interim) data is made even more

difficult by disparate study protocols, including primary

endpoints (such as what is considered a COVID-19

case, and when is this assessed), types of placebo, study

populations, background risks of COVID-19 during the

study, duration of exposure, and different definitions

of populations for analyses both within and between

studies, as well as definitions of endpoints and statistical

methods for efficacy. Importantly, we are left with the

unanswered question as to whether a vaccine with a

given efficacy in the study population will have the same

efficacy in another population with different levels of

background risk of COVID-19. This is not a trivial question

because transmission intensity varies between countries,

affected by factors such as public health interventions

and virus variants. The only reported indication of

vaccine effectiveness is the Israeli mass vaccination

campaign using the Pfizer–BioNTech product. Although

the design and methodology are radically different from

the randomised trial,2

Dagan and colleagues11 report an

RRR of 94%, which is essentially the same as the RRR of

the phase 3 trial (95%) but with an ARR of 0·46%, which

translates into an NNV of 217 (when the ARR was 0·84%

and the NNV was 119 in the phase 3 trial). This means in

a real-life setting, 1·8 times more subjects might need

to be vaccinated to prevent one more case of COVID-19

than predicted in the corresponding clinical trial.

Uncoordinated phase 3 trials do not satisfy public

health requirements; platform trials designed to address

public health relevant questions with a common

protocol will allow decisions to be made, informed

by common criteria and uniform assessment. These

considerations on efficacy and effectiveness are based

on studies measuring prevention of mild to moderate

COVID-19 infection; they were not designed to conclude

on prevention of hospitalisation, severe disease, or

death, or on prevention of infection and transmission

potential. Assessing the suitability of vaccines must

consider all indicators, and involve safety, deployability,

availability, and costs.

We declare no competing interests.

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access

article under the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

*Piero Olliaro, Els Torreele, Michel Vaillant

piero.olliaro@ndm.ox.ac.uk

Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Medicine,

University of Oxford, Oxford OX3 7FZ, UK (PO); Institute for Innovation and

Public Purpose, University College London, London, UK (ET); Competence Center

for Methodology and Statistics, Luxembourg Institute of Health, Strassen,

Luxemburg (MV)

1 Zimmer C, Corum J, Wee S-L. Covid-19 Vaccine Tracker. https://www.

(accessed March 10, 2021).

2 Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2

mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 2603–15.

3 Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273

SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 403–16.

4 Voysey M, Clemens SAC, Madhi SA, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1

nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of

four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK.

Lancet 2021; 397: 99–111.

5 Logunov DY, Dolzhikova IV, Shcheblyakov DV, et al. Safety and efficacy of an

rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine:

an interim analysis of a randomised controlled phase 3 trial in Russia. Lancet

2021; 397: 671–81.

6 US Food and Drug Administration. Vaccines and Related Biological Products

Advisory Committee meeting: FDA briefing document. Dec 10, 2020.

https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/

vaccines-and-related-biological-products-advisory-committee-december10-2020-meeting-announcement (accessed March 10, 2021).

7 US Food and Drug Administration. Vaccines and Related Biological Products

Advisory Committee meeting: FDA briefing document. Dec 17, 2020.

https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/

vaccines-and-related-biological-products-advisory-committee-december17-2020-meeting-announcement (accessed March 10, 2021).

8 US Food and Drug Administration. Vaccines and Related Biological Products

Advisory Committee meeting: FDA briefing document. Feb 26, 2021.

https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/

vaccines-and-related-biological-products-advisory-committee-february26-2021-meeting-announcement (accessed March 10, 2021).

9 Olliaro P. What does 95% COVID-19 vaccine efficacy really mean?

Lancet Infect Dis 2021; published online Feb 17. https://doi.org/10.1016/

S1473-3099(21)00075-X.

10 Brown RB. Outcome reporting bias in COVID-19 mRNA vaccine clinical

trials. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021; 57: 199.

11 Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, et al. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in a

nationwide mass vaccination setting. N Engl J Med 2021; published online

Feb 24. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2101765

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?